1 Área Académica de Medicina del Instituto de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, 42090 Pachuca, Hidalgo, Mexico

Abstract

Primary dysmenorrhea is one of the main chronic pain conditions in women and is often associated with various psychiatric disorders and some painful conditions. Women with dysmenorrhea report the presence of abdominal and lumbar allodynia at the end of the menstrual cycle, suggesting an association between menstrual pain and increased mechanical hypersensitivity in the abdominal and lumbar regions. Therefore, the general objective of this study was to measure pressure pain thresholds and depressive and anxiety symptoms in Mexican women with primary dysmenorrhea.

This prospective cohort study used a cross-sectional design with female students; being older than 17 years of age, being available during menstruation, and having moderate-to-severe primary dysmenorrhea diagnosed by a physician were inclusion criteria. After providing informed consent, the women completed a questionnaire assessing demographic information, variations in menstrual patterns, and menstrual pain and its severity. Similarly, the Beck Depression Inventory and Anxiety Inventory were administered to the participants prior to obtaining pressure pain thresholds at specific abdominal and lumbar points. The data were entered into a computerized database. Exploratory analysis was performed via Student’s t test, Pearson’s chi-square test, or analysis of variance. Statistical significance was considered when p < 0.05.

A total of 69 women were included in the study. The mean ± standard deviation age of all participants was 20.9 ± 1.9 years. The main locations of menstrual pain were the lower abdomen (87.0%) and the lumbar region (10.1%). In terms of pain severity, 65.2% of the participants reported moderate pain, and 34.8% reported severe pain. With respect to the pain pressure threshold at the six evaluated points, the threshold in the abdominal region was significantly lower than the threshold in the lumbar region (p < 0.05). No relationship was found between the severity of dysmenorrhea pain and the level of depression or anxiety or with the pain pressure thresholds (p > 0.05).

The severity of dysmenorrhea pain in the participating women was not associated with anxiolytic or depressive states. No significant relationship was found between the severity of dysmenorrhea and the sensitivity of the pressure pain threshold in the areas evaluated.

Keywords

- depression

- mexican women

- pain pressure threshold

- primary dysmenorrhea

Painful menstrual cramps or dysmenorrhea is considered one of the most important chronic pain syndromes in women because they are persistent, potentially life-disturbing, and associated with negative cognitive, behavioral, sexual, or emotional impacts [1]. Primary dysmenorrhea can occur several cycles after menarche, and the global prevalence of dysmenorrhea ranges from 28% to 94% in some populations [2, 3, 4, 5]. Several risk factors have been related with the presence of pain and physical and psychological symptoms in primary dysmenorrhea, including smoking, alcohol consumption, family history of dysmenorrhea, long or heavy menstrual cycles, early menarche, and daily life stressors such as exposure to natural disasters, extreme violence, or pandemics such as the recent one caused by Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) [6, 7, 8, 9]. All of these changes are related to the modulation of the menstrual cycle by the hypothalamic‒pituitary‒gonadal axis and related hormones. The menstrual cycle is regulated by a complex interaction of hormones: luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and female sex hormones (estrogen and progesterone) [10, 11]. The menstrual cycle consists of three phases, the follicular phase (before the release of the ovum, where the levels of estrogen and follicle stimulating hormone are the protagonists), the ovulatory phase (there is the release of the ovum due to an increase in the concentration of luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating), and the luteal phase (the corpus luteum is formed and lasts until a new menstruation occurs if the woman has not become pregnant) [10, 11].

Several psychological disorders have been identified with regard to the menstrual period, such as premenstrual syndrome (PMS), premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), eating disorders, and depression or anxiety, especially at the end of the luteal phase [12]. PMS includes physical (e.g., breast pain, headaches, and sleep disturbances) and psychological (e.g., irritability, depression, and fatigue) symptoms that begin several days before menstruation and end at the beginning of or a few hours after menstruation. On the other hand, a severe increase in the intensity of PMS symptoms causes PMDD [12, 13]. Painful conditions and syndromes have also been reported, such as migraine, temporomandibular disorders, menstrual colic, and others, which have been linked to the oscillating release of hormones during different stages of the menstrual cycle [11]. In primary dysmenorrhea, the origin of pain is due to the cessation of progesterone and estrogen release and the release of prostaglandins at the level of the endometrium, with subsequent sensitization of nociceptors innervating the uterus and adjacent tissues [14]. Prostaglandins cause strong and intermittent uterine contractions that women report as cramping pain [3, 14]. These cramping pains are felt or referred to different areas, such as the lower abdominopelvic quadrants, the lower back or lumbar region, and the thighs [3, 14, 15]. Likewise, allodynia has been demonstrated in the abdominal and lumbar regions during menstrual pain [16]. In general, the location of dysmenorrheic pain has been determined in cross-sectional epidemiologic studies using unimodal questions and, in some cases, multimodal questionnaires [3, 14]. Only a few studies have determined the sensitivity of the main painful sites reported in cases of primary dysmenorrhea [15, 16, 17]. Consequently, the present study focused on determining the pressure pain threshold and depressive and anxiety symptoms in Mexican women with primary dysmenorrhea.

This prospective cohort study used a cross-sectional design with female students from the Institute of Health Sciences.

The participants were selected from the local Health Sciences Institute of the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo (UAEH), Pachuca, Hidalgo, Mexico. Patients who agreed to participate in the research, signed informed consent, were over 17 years old, were available during menstruation, and had moderate-to-severe primary dysmenorrhea diagnosed by a physician (who first took a medical history and performed a physical examination) were included. Women were excluded if they had missing values, low back pain, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, wounds or lesions of the abdominal or lumbar skin, recent trauma to the areas to be assessed, a body mass index greater than 29.9 kg/m2, strenuous exercise for more than 120 minutes per week, pregnancy or suspected pregnancy, use of contraceptives or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, analgesics (acetaminophen, opioids, or similar), or benzodiazepines in the previous 48 hours. A sample collected sequentially from 69 participants had complete data and was included in the analyses.

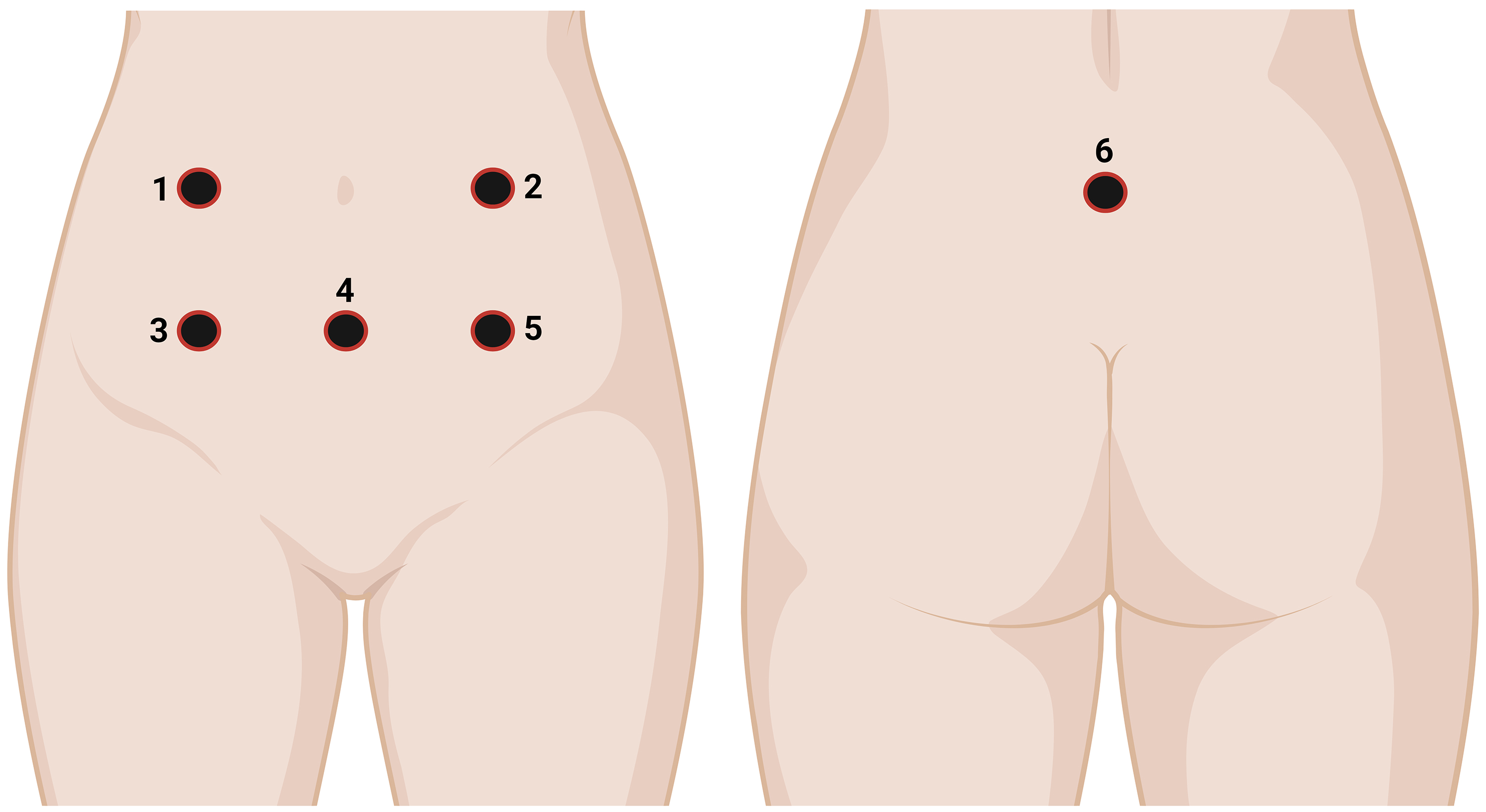

A questionnaire was developed and administered to the participants prior to obtaining the pressure pain threshold. Demographic information, menstrual cycle variations, menstrual pain and severity, the Beck Depression Inventory, and the Beck Anxiety Inventory were included in the questionnaire. Dysmenorrhea was defined as “painful periods in the last 3 months”, and the level of pain was assessed via a 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS), ranging from “no pain” to “the worst imaginable pain”. After completing the questionnaire, the women went to the doctor’s office for measurement of their pressure pain threshold with a hand-held electronic algometer (Wagner Force One™FDIX, Wagner Instruments, Greenwich, CT, USA) with pressure applied at a constant rate of 30 kPa/second. For the measurements, the algometer was mounted with a 1 cm2 rubber tip, and pressure was applied at each specified location. The pressure pain threshold was defined as the pressure (kPa) at which the patient’s perceived sensation changed from no pain to pain. The participants reported the actual pressure when the pain threshold was reached. The final pain threshold was the average of two pain threshold measurements in kPa with an interstimulus interval of 30 seconds. Six sites were evaluated: Points 1 and 2, bilaterally 4 cm from the umbilicus; Points 3 and 5, 4 cm below the previous points; Point 4, 4 cm from the inferior border of the umbilicus; and Point 6, on the medial side of the lumbar region below the fifth lumbar vertebra (corresponding to sacral 2–4 sections; Fig. 1) [18].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the six sites used to evaluate the pressure pain threshold. Six sites were evaluated: Points 1 and 2, bilaterally 4 cm from the umbilicus; Points 3 and 5, 4 cm below the previous points; Point 4, 4 cm from the inferior border of the umbilicus; and Point 6, on the medial side of the lumbar region below the fifth lumbar vertebra (corresponding to sacral 2–4 sections).

A computerized database was created for the numerical and nominal data

collected. Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were performed via

the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 24.0 for Windows (SPSS

Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Exploratory analysis was performed via Student’s

t test, Pearson’s chi-square test, and post hoc analysis of variance

(ANOVA) with the Bonferroni correction. p

A total of 69 women with dysmenorrhea were included in the study. The severity of dismenorrheal pain was moderate in 45 women (65.2%) and severe in 24 women (34.8%). Age, age at menarche, menstrual characteristics, and depressive and anxiety states analyzed for dysmenorrhea pain severity are shown in Table 1.

| Total | Moderate pain | Severe pain | Statistical values | p values | ||

| (n = 69) | (n = 45) | (n = 24) | ||||

| Age (years, mean |

20.9 |

21.0 |

20.8 |

t = 0.302 | 0.764 | |

| Menarche (years, mean |

12.4 |

12.6 |

12.0 |

t = 1.517 | 0.134 | |

| Cycle pattern n (%) | ||||||

| Regular | 49 (71.0) | 30 (66.7) | 19 (79.2) | 0.276 | ||

| Irregular | 20 (29.0) | 15 (33.3) | 5 (20.8) | |||

| Frequency of menstruation n (%) | ||||||

| 21–30 days | 40 (58.0) | 23 (51.1) | 17 (70.8) | 0.114 | ||

| 29 (42.0) | 22 (48.9) | 7 (29.2) | ||||

| Duration of menstruation n (%) | ||||||

| 1–5 days | 44 (63.8) | 29 (64.4) | 15 (62.5) | 0.873 | ||

| 25 (36.2) | 16 (35.6) | 9 (37.5) | ||||

| Amount of flow n (%) | ||||||

| Moderate | 42 (60.9) | 30 (66.7) | 12 (50.0) | 0.177 | ||

| Heavy | 27 (39.1) | 15 (33.3) | 12 (50.0) | |||

| Depression n (%) | ||||||

| Minimal | 26 (37.7) | 19 (42.2) | 7 (29.2) | 0.142 | ||

| Mild | 15 (21.7) | 11 (24.2) | 4 (16.7) | |||

| Moderate | 13 (18.8) | 9 (20.0) | 4 (16.7) | |||

| Severe | 15 (21.7) | 6 (13.3) | 9 (37.5) | |||

| Anxiety n (%) | ||||||

| Minimal | 8 (11.6) | 7 (15.6) | 1 (4.2) | 0.354 | ||

| Mild | 20 (29.0) | 11 (24.4) | 9 (37.5) | |||

| Moderate | 18 (26.1) | 13 (28.9) | 5 (20.8) | |||

| Severe | 23 (33.3) | 14 (31.1) | 9 (37.5) | |||

SD, standard deviation.

The participants reported having dysmenorrhea for an average of 8.1

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Symptomatology | Factors that relieve the pain | ||||

| Swollen abdomen | 60 (87.0) | Medicines | 36 (52.2) | ||

| Depression | 55 (79.7) | Local heat | 15 (21.7) | ||

| Painful or tender breasts | 44 (63.8) | Repose | 12 (17.4) | ||

| Gastrointestinal disturbances | 31 (44.9) | Teas or infusions | 4 (5.8) | ||

| Anxiety | 30 (43.5) | Exercise | 2 (2.9) | ||

| Headache | 29 (42.0) | Factors that aggravate the pain | |||

| Beginning of the symptomatology | Stress | 43 (62.3) | |||

| 1–2 days before menses | 27 (39.1) | Running or physical activity | 15 (21.7) | ||

| First day of menstruation | 16 (23.2) | Exercise | 15 (21.7) | ||

| A few days after menstruating begins or variable | 26 (37.7) | Food | 9 (13.0) | ||

| Main location of menstrual pain | Insomnia | 2 (2.9) | |||

| Belly, lower abdomen | 60 (87.0) | ||||

| Lumbar area | 7 (10.1) | ||||

| Breasts | 2 (2.9) | ||||

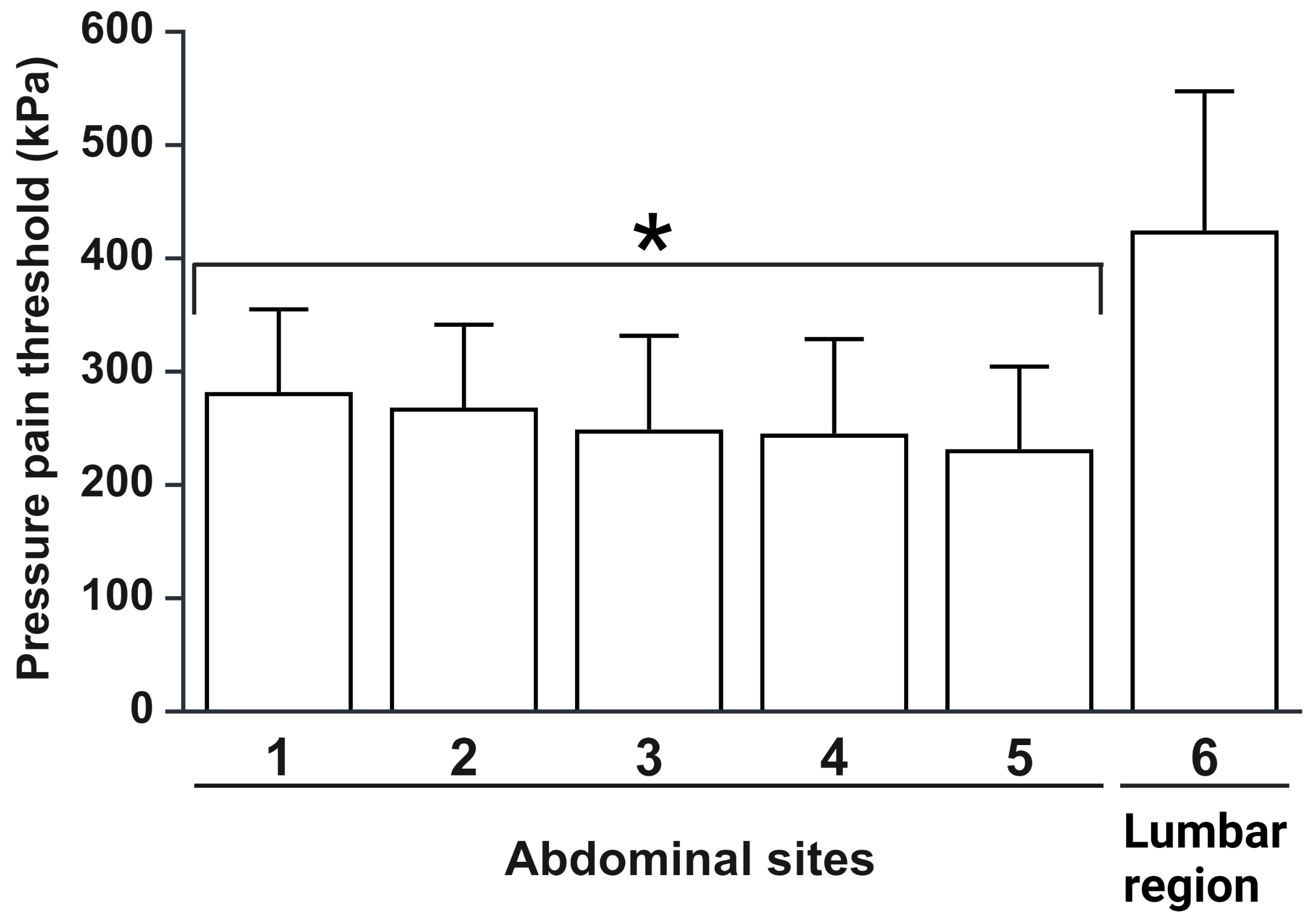

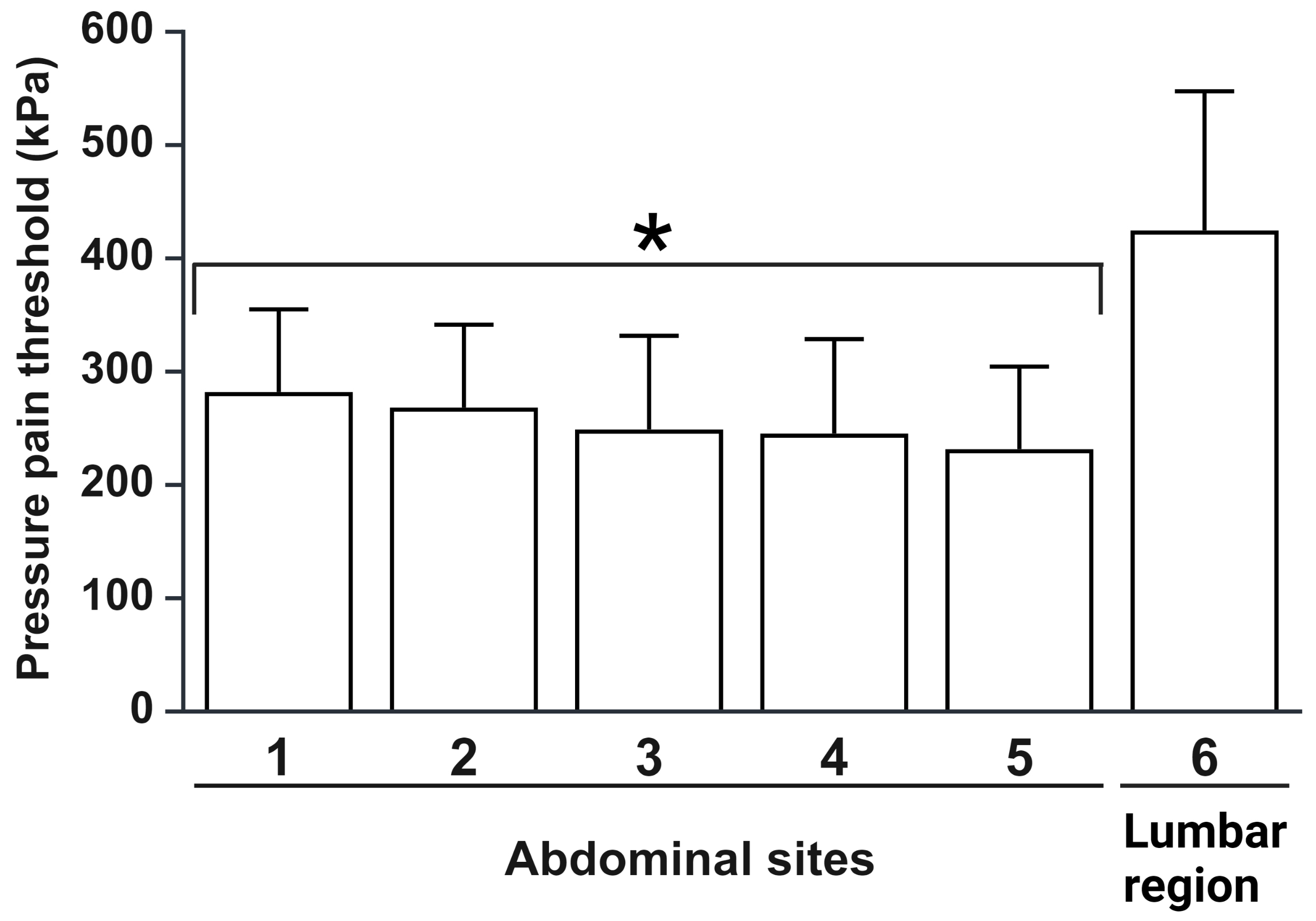

The values of the pressure pain thresholds at the six evaluated points in the

dysmenorrhea group are shown in Fig. 2. The thresholds in the abdominal regions

(points 1–5) were significantly lower than the threshold in the lumbar region

(point 6) (p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Pressure pain threshold in the menstrual phase of the cycle of

the participants (n = 69). Data are shown as the mean

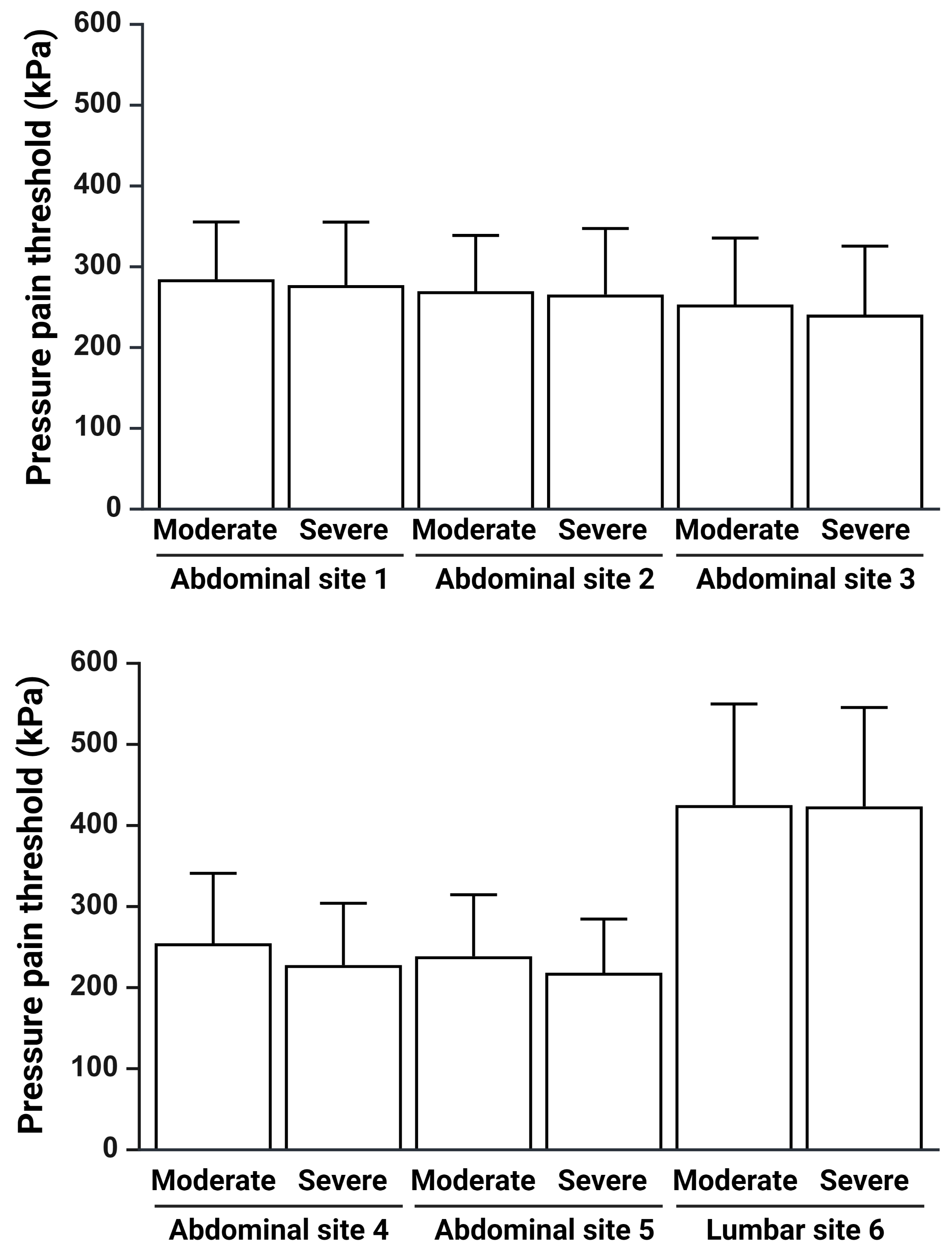

Fig. 3.

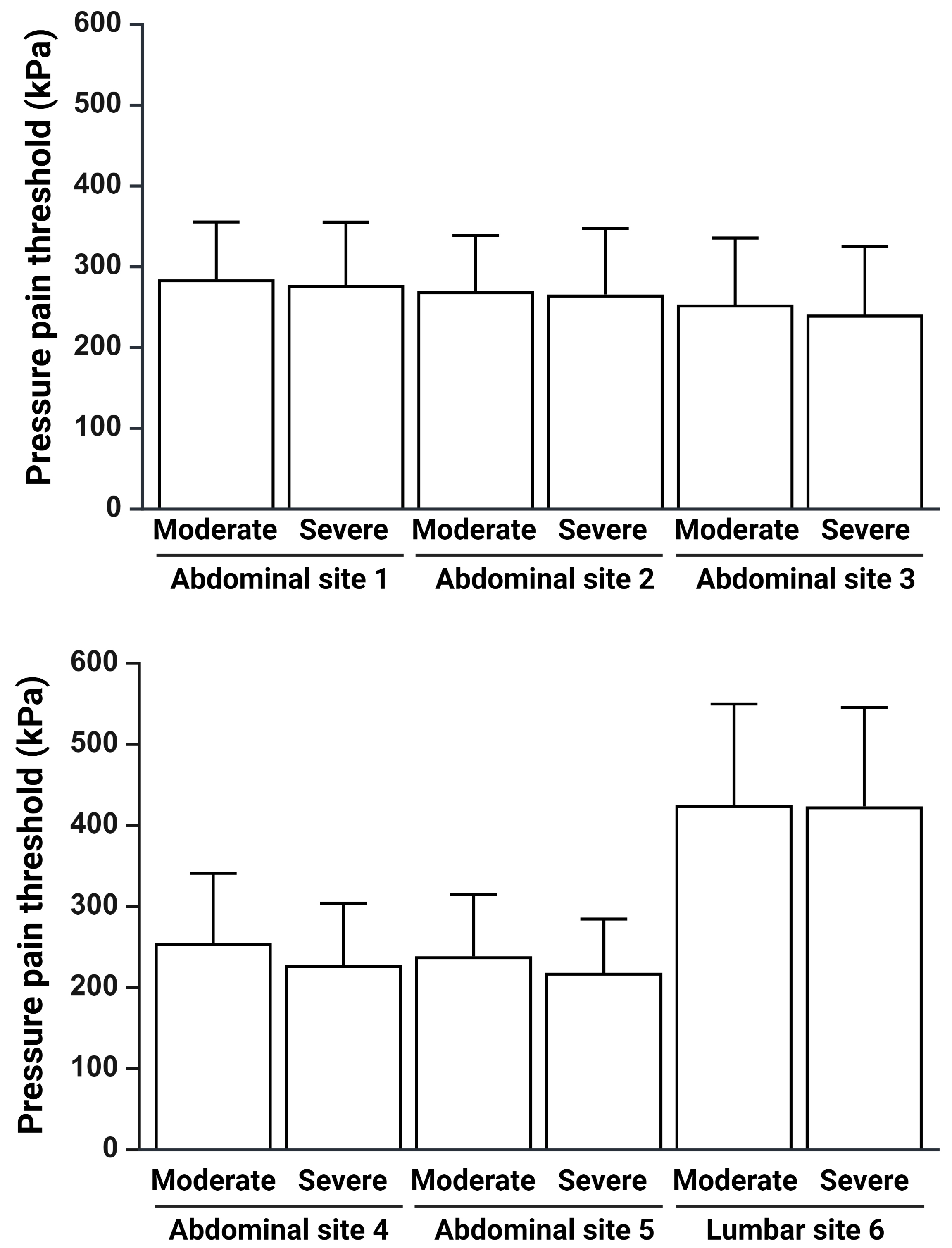

Fig. 3.

Pressure pain threshold in the menstrual phase of the cycle in

participants according to the severity of dysmenorrheic pain (moderate or

severe). Data are shown as the mean

The present study revealed that 65.2% of the participants reported moderate pain, and 34.8% reported severe pain. The most common locations of menstrual pain reported were the lower abdomen (87.0%), lumbar region (10.1%), and breasts (2.9%). The pressure pain thresholds in the abdominal region were significantly lower than those in the lumbar region. No relationship was found between the severity of dysmenorrheic pain (moderate versus severe) and the participants’ pressure pain thresholds.

Our findings on the presence of depression in dysmenorrhea women are consistent with the presence of depression in 31.4% and 48.4% of high school and university students with dysmenorrhea, respectively [19, 20]. A relatively recent meta-analysis reported a statistically significant 25.2% prevalence of depression in women with primary dysmenorrhea and demonstrated that women with this condition had a 1.72-fold increased risk of experiencing depressive symptoms compared with women without dysmenorrhea [21]. Depression is a mood disorder that affects the way a person feels, enjoys life, thinks, and carries out daily activities such as studying, sleeping, eating, or working. In patients with PMS or PMDD, depression and other mood changes can occur in the days before menstruation begins. These changes may last for a few days, and some women experience depression even after menstruation has stopped [10, 12, 13, 14]. The presence of depression in some women at the end of the luteal phase has been linked to decreases in estrogen and progesterone and to psychosocial factors [10, 12, 13, 14]. Pain and depression are factors that reduce women’s productivity at school or work. In this sense, it is important that health professionals try to identify this change in mood and pain intensity in women with primary dysmenorrhea to provide psychological support and more comprehensive care. In the present study, no significant relationships were found between the severity of dysmenorrhea-related pain and depression and anxiety. A probable explanation is that since all the participants are students, the depression and anxiety they experience in their daily lives as students is homogeneous in both pain levels of the participants with dysmenorrhea.

In this study, the lower abdomen and lumbar region were the main areas of pain reported by the participants. This last finding is largely consistent with the results of several studies that have identified these areas as the main sites of pain perception [3, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Because the sensory and motor innervation of abdominal structures is diffuse and can occur in multiple forms, different types and locations of pain can be difficult to diagnose. In this sense, abdominal pain may be visceral (stimulation of autonomic nerves located in the visceral peritoneum covering the abdominal viscera), parietal (due to chemical irritation or other inflammatory processes affecting the parietal peritoneum), referred (pain felt in an area far from the site of affection), or neurogenic (occurring in the path of an affected nerve) [22, 23, 24]. Epidemiological data, diagnostic methods (interview, palpation, percussion, auscultation), and experimental methods have been used to identify different sites of pain perception in patients with abdominal pathologies [22, 23, 24]. In general, pain due to dysmenorrhea has the characteristics of a type of visceral and referred pain produced by spasms of the muscle that make up the uterine cavity, reflected as cramps that reach a certain level of intensity and then subside, repeating in cycles, which is known as cramping pain [3, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20].

In the present study, participants’ pressure pain thresholds were lower in the abdominal region than in the lumbar region. Our results are consistent with the findings of a study in which minor mechanosensitivity to pressure in the lumbar region in women with dysmenorrhea was reported by Serrano-Imedio et al. [25]. Recent evidence has revealed a relationship between local and referred pain in dysmenorrhea and the stimulation of myofascial trigger points (located when a tender point in the muscles is palpated), which can cause local and central sensitization, resulting in a decrease in the threshold to pressure or other types of stimuli in the abdominal and extra-abdominal areas (pelvic floor, lower lumbar region, etc.) [26]. In support of the latter, local lidocaine administration to myofascial trigger points in dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain has demonstrated analgesic efficacy [27, 28]. In summary, evidence shows that there is increased sensitivity to touch and mechanical pressure in the lumbar, abdominal, and lower extremity regions in women with dysmenorrhea, which correlates with the menstrual cycle. Therefore, these findings should be considered in the comprehensive management of patients with dysmenorrhea, especially those with severe pain that is often refractory to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or oral contraceptives. Injections into myofascial trigger points can be considered without an injector (dry needling) or with lidocaine, corticosteroids, or botulinum toxin [27, 28, 29].

The lack of more tests to diagnose depression is a limitation of the present study. In this case, the Beck Depression Inventory was the only instrument used to determine the depressive state of the participants. Although these depression and anxiety inventories have been widely used and validated in different populations, it is suggested that more tests be used in future studies to arrive at more accurate diagnoses.

In conclusion, the severity of dysmenorrheic pain in the participants was not associated with anxiolytic or depressive states. The participants had a greater pain threshold to pressure in the lumbar region than in the abdominal region. No significant relationship was found between the severity of dysmenorrhea and the sensitivity of the pain threshold to pressure in the evaluated areas.

Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [MIO] on request.

MIO: designed the research study, performed the research, provided help and advice on all the manuscript, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript, read and approved the final manuscript. MIO has participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Health Sciences, UAEH, Pachuca, Hidalgo, Mexico (approval number: CEEI-007-2020). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.