1 Department of Obstetrics, Jiangxi Maternal and Child Health Hospital, 330006 Nanchang, Jiangxi, China

2 Department of Anesthesiology, Jiangxi Provincial People’s Hospital (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang Medical College), 330006 Nanchang, Jiangxi, China

Abstract

This study aims to compare the efficacy of two insulin administration methods — continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) and multiple daily injections (MDI) — in managing glycemic levels and influencing pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) patients.

In total, 118 GDM patients admitted between January 2021 and May 2023 were randomly allocated into two groups using a computer-generated sequence. Patients in the MDI group received multiple daily injections, while those in the CSII group received continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion via an insulin pump. The study duration lasted from diagnosis until delivery. Glycemic control was measured by monitoring fasting blood glucose (FBG), postprandial blood glucose (PBG), and bedtime blood glucose (BBG) levels. Pregnancy outcomes included the incidence of hypoglycemia, premature rupture of membranes, postpartum hemorrhage, fetal distress, macrosomia, neonatal asphyxia, and preterm delivery.

Post-treatment, the CSII group showed better control of FBG, PBG, and BBG, which were significantly lower compared to the MDI group (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the incidence rates of complications such as hypoglycemia, fetal distress, neonatal asphyxia were significantly lower in the CSII group compared to the MDI group (p < 0.05).

CSII offers better treatment outcomes for GDM patients compared to MDI. It effectively regulates blood glucose levels, optimizes pregnancy outcomes, and minimizes the risk of neonatal complications. Hence, CSII deserves further clinical endorsement and application.

The study has been registered on Chinese Clinical Trial Registration https://www.chictr.org.cn/ (registration number: ChiCTR2400088927).

Keywords

- gestational diabetes mellitus

- continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion

- multiple daily injections

- pregnancy outcomes

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) occurs when a pregnant woman with no prior history of diabetes or abnormal glucose tolerance develops reduced glucose tolerance or diabetes during pregnancy [1]. It is a common complication characterized by hyperglycemia due to abnormal glucose metabolism in pregnant women [2]. Women with GDM have a higher risk of miscarriage, congenital anomalies, preterm labor, preeclampsia, macrosomia, and stillbirth compared to the general population [3]. Therefore, managing GDM primarily aims to control blood glucose levels effectively for optimal maternal and fetal health.

After early lifestyle interventions (diet and physical activity) fail, insulin therapy becomes the most effective treatment for GDM. It allows for precise glycemic control without crossing the placenta, ensuring safety for both mother and fetus. This treatment reduces the risk of pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia and macrosomia and improves long-term health outcomes for the baby [4, 5]. However, the best method of insulin administration remains debated. The two prevalent modes are multiple daily injections (MDI) and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII). Comparative studies in non-pregnant diabetic patients show CSII provides better glycemic control, quality of life, reduced severe hypoglycemia, and lower daily insulin requirements [6]. The findings also suggest that CSII might also improve glycemic control and pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women [7].

Despite the potential advantages of CSII, there is limited research on its efficacy compared to MDI in GDM pregnant women. Previous studies focused on general insulin therapy effectiveness in GDM without comparing different administration methods [8]. This highlights the need for further research to determine the best insulin delivery method for optimizing glycemic control and pregnancy outcomes in GDM patients.

This study compares the impact of MDI and CSII on glycemic control effectiveness in GDM patients and their subsequent influence on pregnancy outcomes. By addressing this knowledge gap, we aim to provide clearer guidance on the optimal insulin administration method for managing GDM, ultimately improving maternal and neonatal health outcomes.

This was a randomized controlled trial conducted at our hospital from January 2021 to May 2023. The hospital admitted approximately 50 pregnant women with GDM per month. The standard protocol included insulin therapy for managing GDM.

1. Diagnosis of GDM in pregnant women was based on a 75-gram oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) conducted at the outpatient clinic department at our hospital. Diagnostic criteria followed those set by the International Association for the Study of Diabetes in Pregnancy (IADPSG) in 2008 [7].

2. After receiving diabetes education, and dietary and exercise interventions for

3–7 days, a blood glucose meter was used to monitor finger blood glucose 7 times

daily (3 times before meals, 3 times 2 hours after meals, and once at bedtime).

Elevated fasting and 2-h postprandial glucose levels were the criteria for

inclusion (fasting and bedtime levels

3. Single pregnancy.

4. Good adherence to treatment.

1. Patients with anemia (hemoglobin

2. Patients with pre-existing diabetes or other endocrine metabolic diseases before pregnancy.

3. Patients with communication or interaction disorders.

4. Pregnant women with allergic reactions to insulin.

5. Pregnant women suffering from chronic infectious diseases.

6. Patients who used drugs or health supplements affecting glucose metabolism before or during pregnancy.

7. Patients with serious organ dysfunction [9].

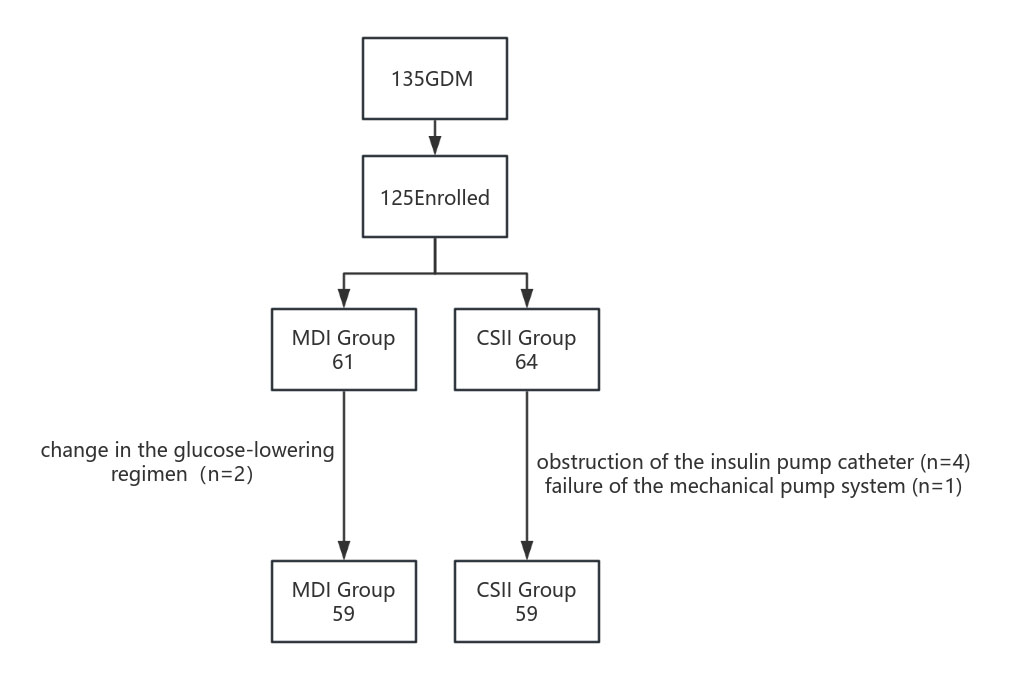

A total of 135 GDM patients were admitted to the hospital from January 2021 to May 2023. Of these, 125 cases met the established enrollment criteria (Fig. 1). The sample size for each arm was calculated using G*Power software (version16.6, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) with the following parameters: effect size (Cohen’s d) of 0.5 (medium effect size), desired power of 80%, and significance level (alpha) of 0.05. Initially, the MDI group included 61 participants, but two were excluded due to a change in the glucose-lowering regimen. The CSII group started with 64 participants; five cases were excluded due to obstruction of the insulin pump catheter (n = 4) and failure of the mechanical pump system (n = 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart over the inclusion process. MDI, daily insulin injections; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; CSII, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion.

Participants were randomly assigned to the MDI or CSII groups using a computer-generated sequence in a 1:1 ratio. Allocation concealment was achieved by sequentially numbering and sealing assignments in opaque envelopes. The randomization list was securely stored in a locked location, inaccessible to investigators. Data were categorized into “Group A” and “Group B” for analysis, with group assignments revealed only after analysis completion.

Data collectors, who are trained healthcare professionals, followed standardized procedures to ensure consistency and accuracy. Missing data were managed using multiple imputations to maintain dataset integrity.

Based on the patient’s physique, gestational week, and weight, the diet was adjusted to meet nutritional needs during pregnancy.

Blood glucose management was accomplished

with subcutaneous injections of rapid-acting insulin, including

NovoRapid (FlexPen NO.S20217021, Novo Nordisk, Bagsværd, Denmark) and

Levemir (FlexPen NO.S20217014, Novo Nordisk, Bagsværd, Denmark). The regimen was: NovoRapid at 0.2–0.3 U/(kg

An insulin pump (version TruCare II, Vertex Medical Equipment, Wuxi, Jiangsu, China.)

was used for NovoRapid (Penfill No. S20153001, Novo Nordisk, Bagsværd, Denmark) administration. The regimen was: a continuous infusion of NovoRapid at 0.4–0.5 U/(kg

SPSS software (version 22.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for

statistical analysis. Data normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. For

normally distributed data, quantitative data are expressed as mean

Fifty-nine participants remained in each group, with no statistically

significant differences in patient characteristics between the two groups

(p

| Group | MDI (n = 59) | CSII (n = 59) | p value |

| Maternal age at delivery (y) | (30.19 |

(30.20 |

0.98 |

| Gestational weeks | (27.15 |

(27.07 |

0.87 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | (23.52 |

(23.56 |

0.83 |

| Primipara | 27 (45.76%) | 28 (47.46%) | 0.85 |

| Passive smoking (Y/N) | 15/44 | 18/41 | 0.54 |

| Family history of diabetes(Y/N) | 6/53 | 5/54 | 0.75 |

| College/university education | 42 | 40 | 0.69 |

| Secondary school or less | 17 | 19 |

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; CSII, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; MDI, multiple daily injections; BMI, body mass index; y, year; Y/N, Yes/No.

Concerning blood glucose levels, no significant differences were observed in

pre-therapy FBG, PBG, and bedtime blood glucose (BBG) between

the two groups (p

| MDI group (n = 59) | CSII group (n = 59) | p value | |

| Pretherapy FBG (mmol/L) | 7.18 |

7.11 |

0.725 |

| post-treatment FBG (mmol/L) | 5.94 |

4.34 |

|

| Pretherapy PBG (mmol/L) | 14.18 |

14.26 |

0.846 |

| post-treatment PBG (mmol/L) | 8.95 |

6.74 |

|

| Pretherapy bedtime blood glucose (mmol/L) | 8.16 |

8.12 |

0.899 |

| Post-treatment bedtime blood glucose (mmol/L) | 7.62 |

6.52 |

FBG, fasting blood glucose; PBG, postprandial blood glucose.

Regarding maternal and neonatal outcomes, no significant differences were found

in the incidence of gestational hypertension, polyhydramnios,premature rupture of

membranes, postpartum hemorrhage, macrosomia, and cesarean section (p

| MDI group (n = 59) | CSII group (n = 59) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational hypertension | 6 (10.17) | 5 (8.47) | 0.752 |

| Polyhydramnios | 4 (6.78) | 2 (3.39) | 0.675 |

| Cesarean section | 24 (40.67) | 18 (30.51) | 0.249 |

| Hypoglycemia | 10 (16.95) | 2 (3.39) | 0.015 |

| Premature rupture | 8 (13.55) | 3 (5.08) | 0.113 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 7 (11.86) | 2 (3.39) | 0.165 |

| Fetal distress | 10 (16.95) | 3 (5.08) | 0.040 |

| Macrosomia | 9 (15.25) | 3 (5.08) | 0.068 |

| Neonatal asphyxia | 11 (18.64) | 3 (5.08) | 0.023 |

| Preterm delivery | 7 (11.86) | 3 (5.08) | 0.186 |

GDM presents significant risks to both mother and fetus if left unmanaged. Early intervention in GDM aims to enhance maternal health and decrease disease prevalence in offspring, underscoring the importance of glycemic control during pregnancy [10, 11]. Insulin, essential for lowering blood glucose, is typically administered through multiple daily injections (MDI) and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII). MDI is the more common method [12]. This study demonstrated that CSII is more effective than MDI in managing blood glucose levels in pregnant women with GDM.

In this study, FBG, PBG, and bedtime glucose levels were significantly lower in

the CSII group compared to the MDI group (p

These findings concur with previous studies that emphasize the advantages of CSII in improving glycemic control and reducing pregnancy-related complications [13]. The superior performance of CSII can be ascribed to its ability to closely mimic physiological insulin secretion, thereby stabilizing blood glucose levels and minimizing fluctuations [14]. This technology permits precise adjustments in insulin delivery, effectively managing fasting hyperglycemia and preventing nocturnal hypoglycemia, which are common challenges in GDM management.

The implications of these findings for clinical practice are profound. Employing CSII in GDM management could improve maternal and neonatal outcomes, reducing complications such as preeclampsia, macrosomia, and neonatal hypoglycemia. Although insulin pumps have high initial costs, some studies suggest these costs could be offset by reduced hospitalization rates, as insulin pumps maintain stable blood glucose levels with a low likelihood of hospital admissions for glucose control [15, 16]. This might also lead to reduced healthcare costs by decreasing hospitalizations and intensive care for both mothers and infants.

CSII enhances glycemic control in patients with GDM and positively impacts pregnancy outcomes, deserving further promotion of insulin pump use.

The study was conducted at a single center, possibly limiting result applicability to other settings. Additionally, the high initial cost of insulin pumps may restrict their widespread use, despite potential long-term savings.

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

XS designed the research study. XS and QC performed the experimental procedures. YS participated in analyzing data, drafting the manuscript, and reviewing and proofreading papers. XS collected some of the patient data and completed follow-up of these patients. SW and SX participated in performance of the operation, patient follow-up, and collection and analysis of data. XS conducted analysis of data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All subjects provided informed consent for inclusion in the study. This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Jiangxi Maternal and Child Health Hospital (approval number: EC-KY-202369).

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript.

This work was supported by Health Commission science and technology plan of Jiangxi Province (No. 202211066).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.