1 Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Korkut Ata University Karacaoğlan Campus, 80000 Osmaniye, Turkey

2 Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Eastern Mediterranean University, 99628 Famagusta, Cyprus

Abstract

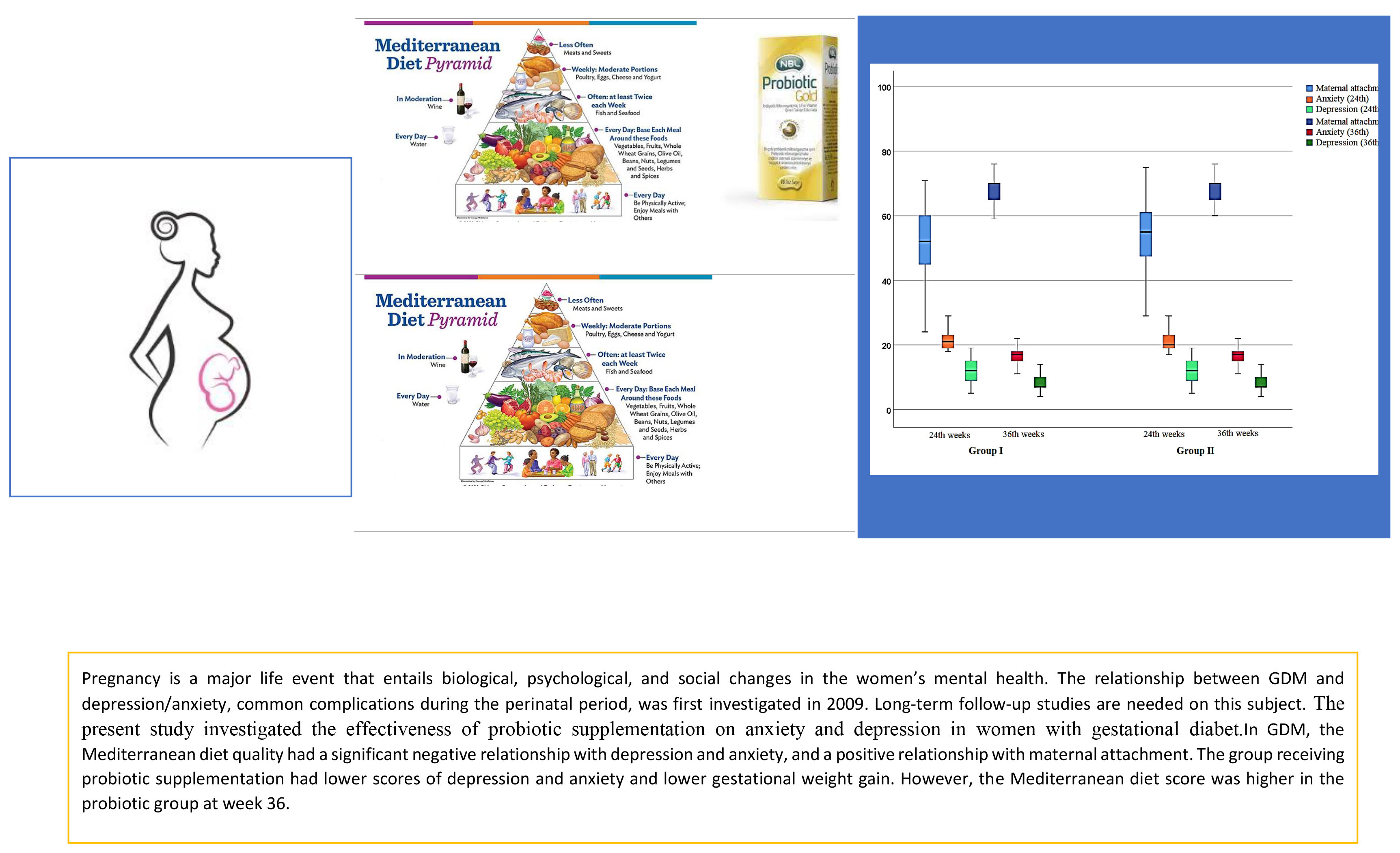

Factors such as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic quarantine, economic decline, and unemployment have an impact on mental health, and have made mental illnesses an important public health problem worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, depression is currently the fourth reason of the global burden of diseas. Evidence shows that women with gestational diabetes (GDM) are at higher risk of developing depression during pregnancy. Despite extensive research carried out by the probiotic industry in recent years, there is a lack of consensus on the available evidence on how best to use probiotics in mental health. Considering the impact of probiotics on mental health, our study aimed to answer the question of whether probiotic supplementation is effective on depression and anxiety in women with gestational diabetes.

In this randomized controlled study with an allocation ratio of 1:1, the participants were divided into two groups: control group, received standard diet compatible with Mediterranean diet (MD) while the probiotic supplementation group received both the standard diet compatible with MD and probiotic supplementation (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium longum and Enterococcus faecium). The participants’ sociodemographic data, medical history, pregnancy data, and adherence to the Mediterranean diet at 24 and 36 weeks of pregnancy were recorded. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Scale (PrAS), and Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (MAAS) scales were used. Two-way repeated measures analysis of variance was used to examine group and time effects and group-time interactions. Additionally, sleep problems, stressful events, and sedentary physical activity were added as exclusion criteria to optimize the impact of potential problems on depression.

In the control and probiotic groups, anxiety scores at 36 weeks of gestation were found to be 16.53 ± 3.49 and 16.27 ± 3.62, respectively (p = 0.771). Maternal attachment scores at 36 weeks of gestation were found to be 67.39 ± 7.56 and 69.29 ± 5.89 in the control and probiotic groups, respectively (p = 0.266). Depression (8.24 ± 2.48; 8.56 ± 2.75, p = 0.627) and anxiety scores during pregnancy and weight gain (12.80 ± 2.97 and 12.07 ± 2.41, p = 0.284) were lower in the probiotic supplementation group at 36 weeks of gestation compared to the control group. The Mediterranean diet score was higher in the probiotic supplement group (33.64 ± 4.92) compared to the control group (31.97 ± 5.18) at week 36. Multiple regression analysis was performed to examine the prediction of depression risk based on the scores obtained from the Med-diet (Mediterranean diet) scale. Accordingly, EPDS (β = –0.57, p = 0.001), PrAS (β = –0.32, p = 0.004), and MAAS (β = 0.78, p = 0.003) significantly predicted the Med-diet score. A one-unit improvement in the Med-diet score resulted in a decrease of 0.57 units in depression, a decrease of 0.3 units in anxiety and an increase of 0.78 units in maternal attachment in both groups.

In GDM, the Mediterranean diet quality had a significant negative relationship with depression and anxiety, and a positive relationship with maternal attachment. The group receiving probiotic supplementation had lower scores for depression and anxiety and lower gestational weight gain. However, the Mediterranean diet score was higher in the probiotic group at week 36.

Registered under ISRCTN registry (https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN96215615) identifier no. ISRCTN96215615.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- gestational diabetes

- maternal mental health

- probiotic supplementation

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a prevalent complication that occurs during pregnancy, characterized by the onset of hyperglycemia first detected during pregnancy [1]. Epidemiological studies have highlighted the increase in the prevalence of GDM [2, 3]. GDM has been observed in 4–16% of pregnant patients and there are variations in its prevalence rates among different countries, with a wide range noted [4, 5]. These variations are attributed to differences in the diagnostic criteria used. One study consistently indicated a significant increase in the prevalence of GDM [6]. The underlying factors contributing to this increase include genetic and sociodemographic variables, as well as the emerging problem of obesity [7].

The existing literature highlights the adverse physical and psychological consequences of GDM for both the mother and the infant [8]. In particular, intervention studies focusing on modifiable risk factors have demonstrated the effect of glycemic control during pregnancy on complications (the development of type 2 diabetes in the mother, macrosomia at birth, and childhood obesity in the infant) [9, 10]. Nutrition-based intervention studies emphasize the importance of nutritional counseling for several reasons, such as having an ideal prepregnancy body weight, adhering to recommended weight gain guidelines set by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) during pregnancy and controlling pathways that trigger GDM, such as oxidative stress [11, 12].

Depressive symptom levels in healthy populations are more common compared to the past years, which poses a risk for public health [8]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depression is currently the fourth reason of the global burden of disease and is predicted to be the most problematic factor that cause any physical or mental disorders by the year 2030 [13].

In addition, the fact that pregnancy is an important life event that causes psychological and social changes requires focusing on depressive symptoms during this period [1]. Symptoms such as sleep disturbance, loss of appetite and energy may be attributed to pregnancy rather than mood changes. This causes depression during pregnancy to be ignored. However, depression and anxiety are the most common mental health disorders during pregnancy [2]. According to the WHO, approximately 10% of pregnant women face mental health problems, predominantly depression or anxiety [14]. It has been reported that 32% of pregnant women in Turkey experience anxiety and 47% experience depression [2]. Mental impairment averages were found to be higher in cases with high risk pregnancies than in cases without risk factors [2, 4, 5]. In addition, the mother-child attachment is the most important relationship in every person’s life, which is formed from the embryonic period and affects the entire subsequent stages of a person’s life, such as social, emotional, and cognitive development [15]. Therefore, it is necessary to determine protective and curative factors for mental health in pregnant patients [6, 7].

The presence of depression, as in diabetes, can also cause impairment in inflammation. The brain is affected by the inflammatory reactions following hyperglycemia. In addition to these pathways, changes in hormone balance during pregnancy have a significant impact on the brain and behaviors. Hence, evidence demonstrates that women with GDM are at higher risk of developing depression during pregnancy. Cases where GDM and depression coexist are frequently observed due to the inflammatory effect. Poor lifestyle, minimal glycemic control and low quality of life are closely associated with this condition [16]. The relationship between GDM and depression/anxiety, common complications during the perinatal period, was first investigated in 2009, revealing an independent correlation between each other [17]. Subsequent studies reported inconsistent results, which could be attributed to factors such as race, gestational period, variations in screening tools for depression, GDM diagnosis criteria and study design [17, 18, 19]. Long-term follow-up studies are needed on this subject. Our study is important because of our intervention from the initial diagnosis to birth.

It is known that nutritional patterns, rather than nutrients, have antidepressive effects through various mechanisms. These mechanisms increase monoamine neurotransmitter biosynthesis, reduce hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and modulate the microbiome-gut-brain axis, exerting potent effects against inflammation-related conditions and oxidative stres [20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. The Mediterranean diet contains high amounts of fruits, vegetables, whole grain cereals, legumes, fish, nuts and olive oil. A useful tool developed by Panagiotakos et al. in 2006 [24] for evaluating Med -diet adherence is the MedDietScore. By investigating the effects of dietary patterns, not just specific nutrients, MedDietScore uses food diaries and food frequency surveys to produce a score associated with beneficial effects on human health.

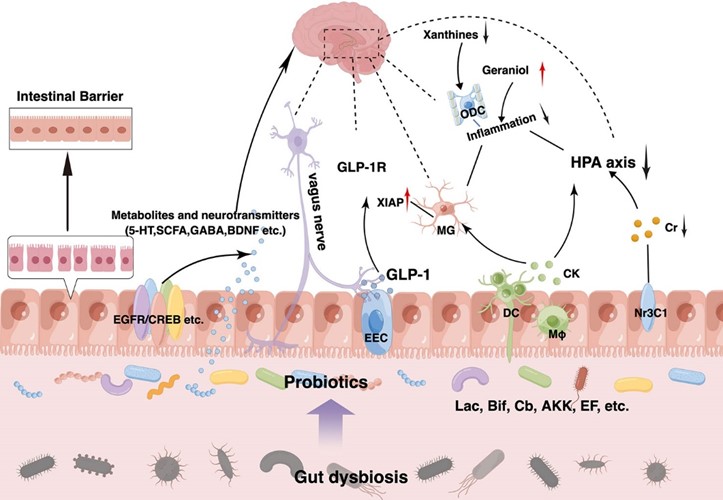

In addition to changes in the gut microbiota, probiotics also have an effect on brain development and behavior. Probiotics effect the central nervous system and produce neuroendocrine molecules. It can reduce proinflammatory cytokine levels and oxidative stress. Probiotics are effective in regulating

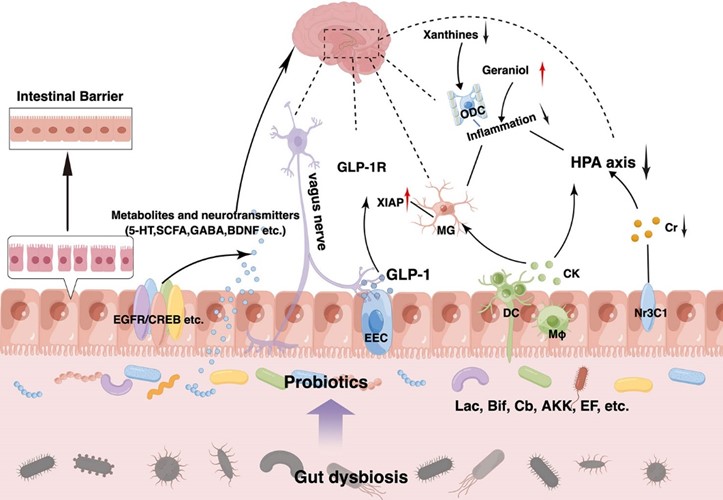

The use of probiotics for the treatment of depression and anxiety was first suggested in 1910 [26], and was reviewed in 2015 [27]. The effect of probiotics on mental health has been investigated in various groups [28, 29], including the pregnancy period [30]. However, there is no study on the mental health of women with GDM. The present study investigated the effectiveness of probiotic supplementation on anxiety and depression in women with GDM (Fig. 1, Ref. [25]).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Possible effect of probiotics on anxiety [25]. GLP-1R; glucagon-like peptide 1; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; GABA, gamma aminobutyric acid; BDNF, Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor; 5-HT, 5-hidroksitriptamin.

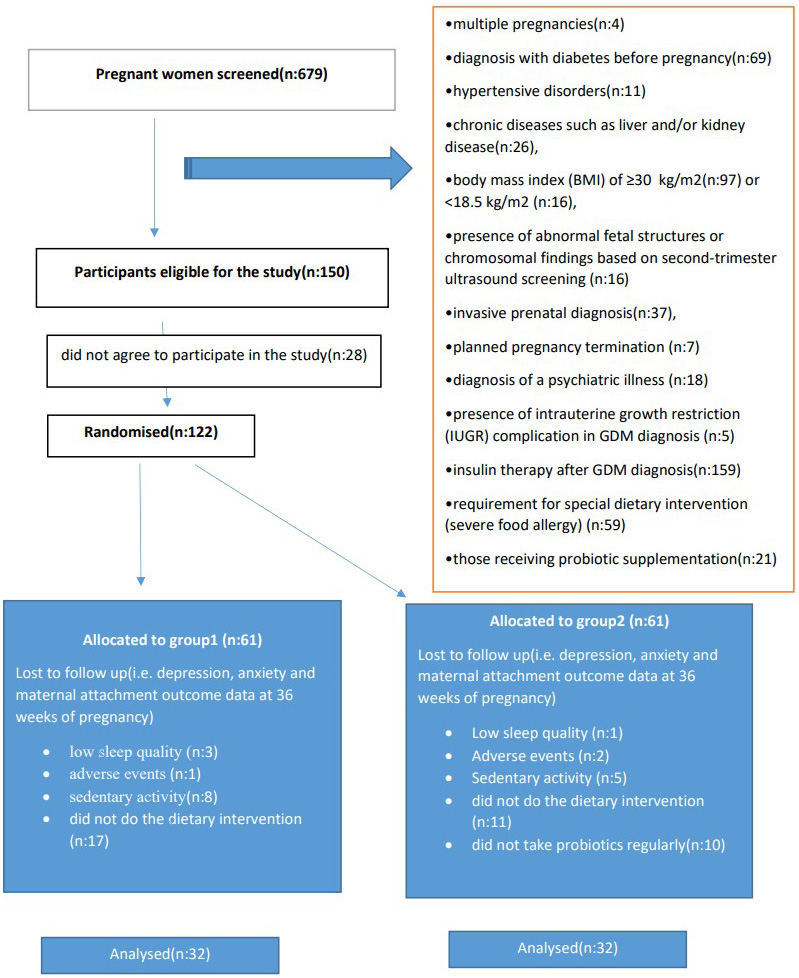

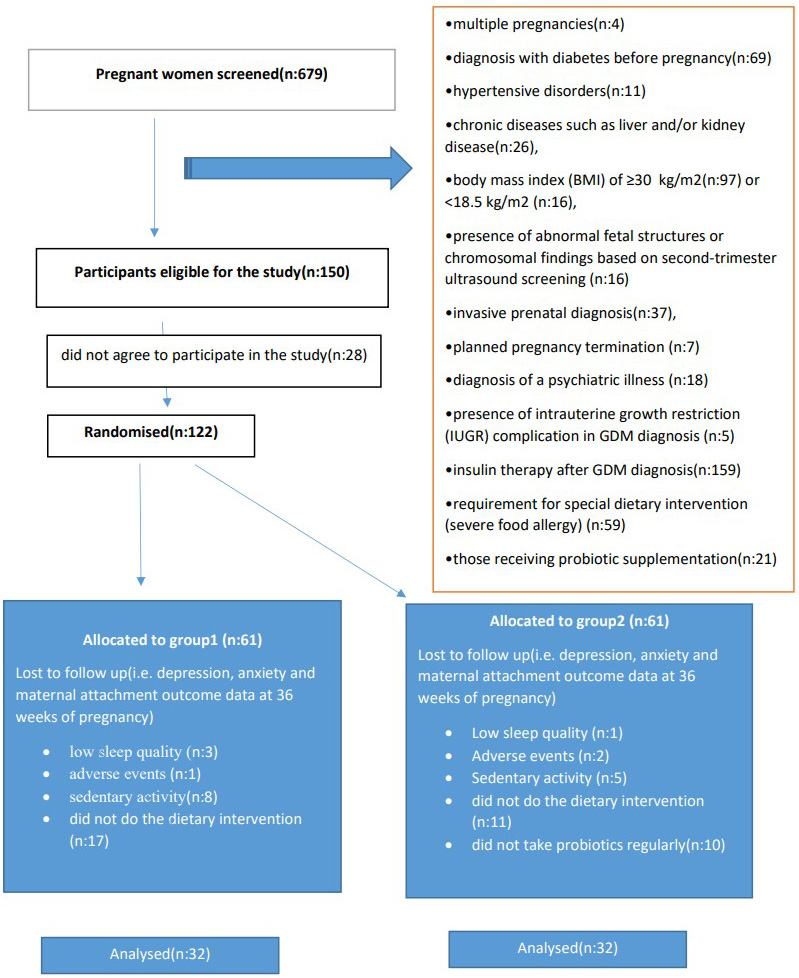

The study was conducted between October 2022 and May 2023 at the Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic of Osmaniye Private Park Hospital using a randomized controlled study design. A total of 679 pregnant patients were identified for the study. Of these, 150 women were diagnosed with GDM and 122 of those diagnosed agreed to participate in the study. Due to adverse effects and non-compliance with the intervention, 64 participants were randomized and randomly divided into 2 groups. All subjects included in the probiotic supplementation group (n = 32) and control group (n = 32) adhered to a medical nutrition therapy (MNT) accordance with the Mediterranean diet for 12 weeks. The gynecologist, who was not involved in the study, created a series with a 1:1 distribution using a random sequence generator. The probiotics administered to the probiotic group were in a random order. The study protocol is presented in a consort diagram (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. CONSORT diagram displaying flow of participant involvement in the study. GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus.

Power analysis [31] was performed to determine the number of samples needed in study. It was accepted that there were two groups and the number of patients in the groups was evenly distributed (n1 = n2). While performing power analysis, the effect size was 0.50, type 1 error was 0.05 and the power of the study was 0.80. When a difference of half a standard deviation (cohen d) between the data of diet and non-diet patients with GDM was considered clinically significant, the required number of patients in each group was determined as 64 with a minimum power of 0.80 and a maximum of 0.05 type I error.

The inclusion criteria for the study were pregnant patients aged between 20 and 40, diagnosed with GDM, body mass index between 18.5 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2, having complete data and agreeing to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria for the study were multiple pregnancies, diagnosed with diabetes before pregnancy, hypertensive disorders, chronic diseases such as liver and/or kidney disease, body mass index (BMI) of

Sleep state: Sleep quality was standardized so that the effect of sleep quality on depression and anxiety would not mask the study results. Sleep was measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). According to this, a total score of

Adverse events: serious adverse events were recorded throughout the study. Three participants were excluded from the study due to negative situations arising from the study [33, 34].

Physical activity: the aim was to control the impact of physical activity status on both energy balance and mental health. The Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire was administered at the beginning of the study (t1) and pregnant patients with sedentary activity (1.5 Metabolic Equivalent of Task (METs)) were excluded [35]. Thirteen participants with MET values below 1.5 were not included.

This was a randomized controlled trial that was approved by the Ethics Committee of Eastern Mediterranean University (approval date: 04.10.2022, approval no: ETK00-2022-0273). The researchers provided all participants in person explanation of the study. The present study was conducted according to guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent was obtained from each participant prior to the study.

The participants’ sociodemographic data, medical history, pregnancy data, and adherence to the Mediterranean diet at 24 and 36 weeks of pregnancy were recorded. Pre-pregnancy body weight and BMI recorded during routine gynecological check-ups were examined retrospectively. Current body weight, pre-pregnancy BMI and current gestational weight gain were monitored by the researchers at the 24th week of pregnancy. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Scale (PrAS), and Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (MAAS) scales were used. The scales were applied by the researchers at the 24th and 36th weeks of pregnancy. At the beginning of the study, a survey containing sociodemographic data was administered to all the participants. The sociodemographic data included participants’ age, marital status, education and profession. The medical history included habits (smoking, alcohol), presence of diabetes mellitus in the family history, history of depression, birth history, delivery method, data related to previous pregnancies, data related to the current pregnancy (pregnancy planning, method of conception), the baby’s gender and data related to postpartum breastfeeding preferences.

This was a single-center randomized controlled trial (parallel groups) designed to investigate the effect of probiotic supplementation on maternal anxiety, depression and antenatal attachment in women with GDM.

With an allocation ratio of 1:1, the participants were divided into two groups: Control group, receiving standard diet compatible with Mediterranean diet (MD), and probiotic supplementation group receiving both the standard diet compatible with MD and probiotic supplementation. The randomization was designed using double-blind randomization. The distribution of the participants was determined by an individual outside the study (Table 1).

| Study Phases | First Visit (week 24) | Intermediate Visit (week 30) | Final Visit (week 36) |

| Signed informed consent | X | ||

| Measuring adherence to the Mediterranean diet | X | X | |

| Scoring of scalesa | X | X | |

| Analysis of potential problemsb | X | ||

| Beginning of dietary intervention | X | ||

| Product distributionc | X | ||

| Clinical assessmentd | X | X | X |

| Diet reminders | X | ||

| Product reminders | X |

a, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Scale, Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale; b, Adverse events, physical activity, sleep state; c, Probiotic use was counted and distributed by researchers to ensure regularity; d, Side effect control was performed by the gynecologist, anthropometric measurements were performed by researchers.

The participants received intervention as per their group. The pregnant patients were enrolled at 24 weeks of gestation and followed up until the 36th week. The first assessment was conducted at the 24th week of pregnancy. The Mediterranean diet adherence at the 24th week of pregnancy, depression, anxiety and antenatal attachment scales were administered. At the 36th week of pregnancy, the Mediterranean diet adherence, depression, anxiety, and antenatal attachment scales were re-administered. The data obtained from the participants were compared between the groups and between the 24th and 36th weeks of pregnancy.

Women aged 20–40 years and diagnosed with GDM as per the International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (ADPSG) criteria and an oral glucose tolerance test were included in the study [36].

The researcher planned a medical nutrition therapy (MNT) according to GDM, accordance with the Mediterranean diet. Enegry requirements were calculated using equations that estimated resting energy expenditure by multiplying the pre-pregnancy weight and height with the physical activity level, as determined by Henry’s equations [37]. Because all participants were in the third trimester, 537 kcal was added. The estimated energy requirement was reduced by 30% if the participant was overweight (prepregnancy BMI

Probiotics exhibit antidepressant properties in the absence of other therapeutic options.Thus, microbiota-based interventions with probiotics may possess greater therapeutic potential for depression treatment, which can be used as an adjunct to current approaches. However, it is important to note that these benefits are strain-specific. We selected some strains that have already played an effective role in the treatment of depression to illustrate the specific mechanism of its action, clarify its dosage, periodicity, and other key information in the current treatment regimen. The group receiving probiotic supplementation was given products containing Lactobacillus acidophilus (4.3

The impact of the Mediterranean diet on maternal mental health was examined. To assess dietary habits, a food frequency questionnaire and a three-day food record were used [24]. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet was examined in the diet assessments. The MedDiet scoring system was used as the assessment tool. This includes the consumption of unrefined grains (whole bread, pasta, rice, other grains, biscuits, etc.), fruits, vegetables, legumes, potatoes, fish, meat and meat products, poultry, whole fat dairy products (such as cheese, yogurt and milk), olive oil and alcohol intake. The scoring ranges from 0 to 55; however, alcohol consumption was not taken into consideration because it is contraindicated in pregnant patients. Therefore, the total score range in this study was from 0 to 50. Higher values of this diet score indicate greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the EPDS, an approved tool for screening antenatal and postnatal depressive symptoms [43]. The 10 item EPDS is the most commonly used depression screening tool in perinatal care; cut-off values of 10 or higher and 13 or higher are most often used to identify women who might have depression [44].

Brunton et al. [45] developed the PrAS, a 33-item Likert-type scale in 2018. Its Turkish validity and reliability study was conducted in 2020 [46].

The approved MAAS evaluated the participant’s relationship with the fetus. The MAAS consists of 5 items rated on a 19-point Likert scale. An increase in the total score obtained from the scale indicates an increase in maternal attachment [47]. The total scores range from 19 to 95, with higher scores indicating a more adaptive maternal-fetal attachment style. The reliability and validity of the MAAS have previously been evaluated [48].

The suitability of variables to normal distribution was examined through visual methods (histograms and probability graphs) and analytical methods (Kolmogorov-Smirnov/Shapiro-Wilk tests). The mean (x) and standard deviation (SD) were used for the analysis of continuous data. To describe categorical variables, the frequency (n) and percentage (%) values were used. Fisher’s exact test and Chi-square test were used to evaluate the relationship between categorical variables. Independent t tests were used to compare the mean scale scores (EPDS, MAAS and PrAS) and diet score of two independent groups. Paired t-test was used to compare repeated measurements of the groups at 24 and 36 weeks. Pearson’s test was used to assess the correlation with every scale outcome. Two-way analysis of variance between groups was performed to examine the effects of the group (probiotic and control) and Mediterranean diet score on anxiety, depression and attachment. Participants’ med-diet scores were divided into with SPSS (version 18.0, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). This classification was carried out as follows; with 30 points or less, between 31 and 33 points, with 34 points and above (Distribution was made according to 25, 50, 75 percent). The statistical significance level was set at p

In general, the participants were aged between 26 and 33 years. Pre-pregnancy BMI of the participants was 27.42

| Diet | Diet | p value | ||

| Group 1 (n = 32) | Group 2 (n = 32) | |||

| x | x | |||

| Age (year) | 29.39 | 29.41 | 0.961 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) (pre-pregnancy) | 27.23 | 27.61 | 0.662 | |

| Increase in body weight (kg) | 12.80 | 12.07 | 0.284 | |

| Diet score (at 24th week) | 29.69 | 29.41 | 0.814 | |

| Pregnancy anxiety (at 24th week) | 20.71 | 20.78 | 0.896 | |

| Maternal attachment (at 24th week) | 51.23 | 53.34 | 0.429 | |

| Depression scale (at 24th week) | 12.01 | 12.06 | 0.912 | |

| Diet score (at 36th week) | 31.97 | 33.64 | 0.191 | |

| Pregnancy anxiety (at 36th week) | 16.53 | 16.27 | 0.771 | |

| Maternal attachment (at 36th week) | 67.39 | 69.29 | 0.266 | |

| Depression scale (at 36th week) | 8.56 | 8.24 | 0.627 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 32 (100) | 30 (93.75) | 0.492 | |

| Single | 0 (0) | 2 (6.25) | ||

| Educational status | ||||

| 7 (21.9) | 4 (13) | 0.320 | ||

| 25 (78.1) | 28 (87) | |||

| Employment status | ||||

| Yes | 25 (78.2) | 26 (81.25) | 0.756 | |

| No | 7 (21.8) | 6 (18.75) | ||

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 5 (15.7) | 7 (24.3) | 0.522 | |

| No | 27 (84.3) | 25 (75.7) | ||

| Alcohol | ||||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 0.492 | |

| No | 32 (100) | 30 (94) | ||

| Delivery history | ||||

| Yes | 19 (59.4) | 17 (53.2) | 0.614 | |

| No | 13 (40.6) | 15 (46.8) | ||

| Prior birth method | ||||

| Vaginal | 9 (47.3) | 6 (35.2) | 0.516 | |

| Cesarean | 10 (52.7) | 11 (64.8) | ||

| Cesarean timing | ||||

| Emergency | 4 (40) | 3 (27.2) | 0.659 | |

| Elective | 6 (60) | 8 (72.8) | ||

| Prenatal depression history in previous pregnancies | ||||

| Yes | 5 (26.4) | 9 (53) | 0.171 | |

| No | 14 (73.6) | 8 (47) | ||

| Postpartum depression history in previous pregnancies | ||||

| Yes | 7 (36.9) | 4 (23.6) | 0.481 | |

| No | 12 (63.1) | 13 (76.4) | ||

| Family history of diabetes mellitus | ||||

| Yes | 18 (56) | 19 (59.3) | 0.800 | |

| No | 14 (44) | 13 (40.7) | ||

| Presence of pregnancy complications in previous pregnancies | ||||

| Yes | 10 (52.6) | 9 (53) | 1.000 | |

| No | 9 (47.4) | 8 (47) | ||

| Number of pregnancies | ||||

| Primipara | 13 (40.6) | 15 (46.8) | 0.614 | |

| Multipara | 19 (59.4) | 17 (53.2) | ||

| Pregnancy planning | ||||

| Planned | 21 (65.6) | 24 (75) | 0.412 | |

| Unplanned | 11 (34.4) | 8 (25) | ||

| Method of conception | ||||

| Natural | 28 (87.5) | 26 (81.25) | 0.491 | |

| Artificial (IVF) | 4 (12.5) | 6 (18.75) | ||

| Sex of the baby | ||||

| Female | 20 (62.5) | 18 (56.2) | 0.611 | |

| Male | 12 (37.5) | 14 (43.8) | ||

| Desire for postpartum breastfeeding | ||||

| Yes | 31 (96.8) | 30 (93.7) | 1.000 | |

| No | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.3) | ||

BMI, body mass index; x, mean; SD, standard deviation; IVF, in vitro fertilization.

The EPDS score decreased significantly from beginning to the end of the intervention (p

| Week 24 | Week 36 | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Group | ||||

| Diet score | 29.69 | 31.97 | 0.064 | |

| Pregnancy anxiety | 20.71 | 16.27 | ||

| Maternal attachment | 51.23 | 67.89 | ||

| Depression scale | 12.01 | 8.56 | ||

| Probiotic supplementation Group | ||||

| Diet score | 29.41 | 33.64 | ||

| Pregnancy anxiety | 20.78 | 16.53 | ||

| Maternal attachment | 53.34 | 68.79 | ||

| Depression scale | 12.06 | 8.24 | ||

There is no significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores of the groups on the anxiety scale (F(1;58) = 0.819; p

| Source of Variance | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effect | |||||||

| Probiotic | 3393 | 1 | 3393 | 0.819 | 0.369 | 0.014 | |

| Med-diet score classification | 21,204 | 2 | 10,602 | 2559 | 0.088 | 0.081 | |

| Error | 240,330 | 58 | 4144 | ||||

| Interactive Effect | |||||||

| Time | 845,184 | 1 | 835,184 | 483,769 | 0.893 | ||

| Time+probiotic | 2228 | 1 | 2228 | 1291 | 0.261 | 0.022 | |

| Time+med diet score classification | 66,042 | 2 | 33,021 | 19,127 | 0.397 | ||

| Time+med diet score classification+probiotic | 7134 | 2 | 3567 | 2066 | 0.136 | 0.067 | |

| Error | 100,132 | 58 | 1726 | ||||

A significant difference was found between the participants’ pre-test and post-test scores (F(1;58) = 483.769; p

The common effect of being in different groups and factors showing measurement at different times on the participants’ anxiety score was not found to be significant (F(2;58) = 2066; p

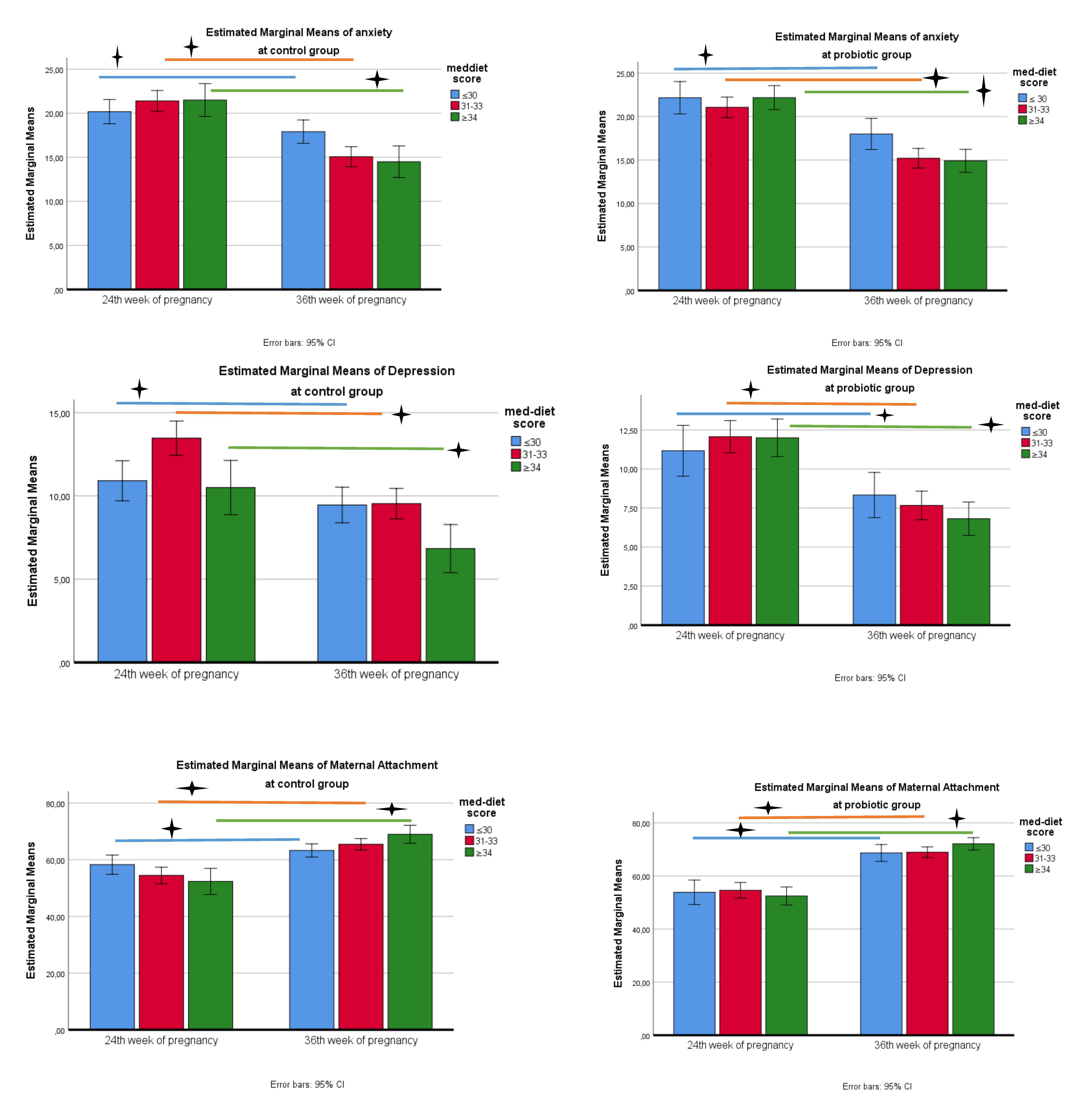

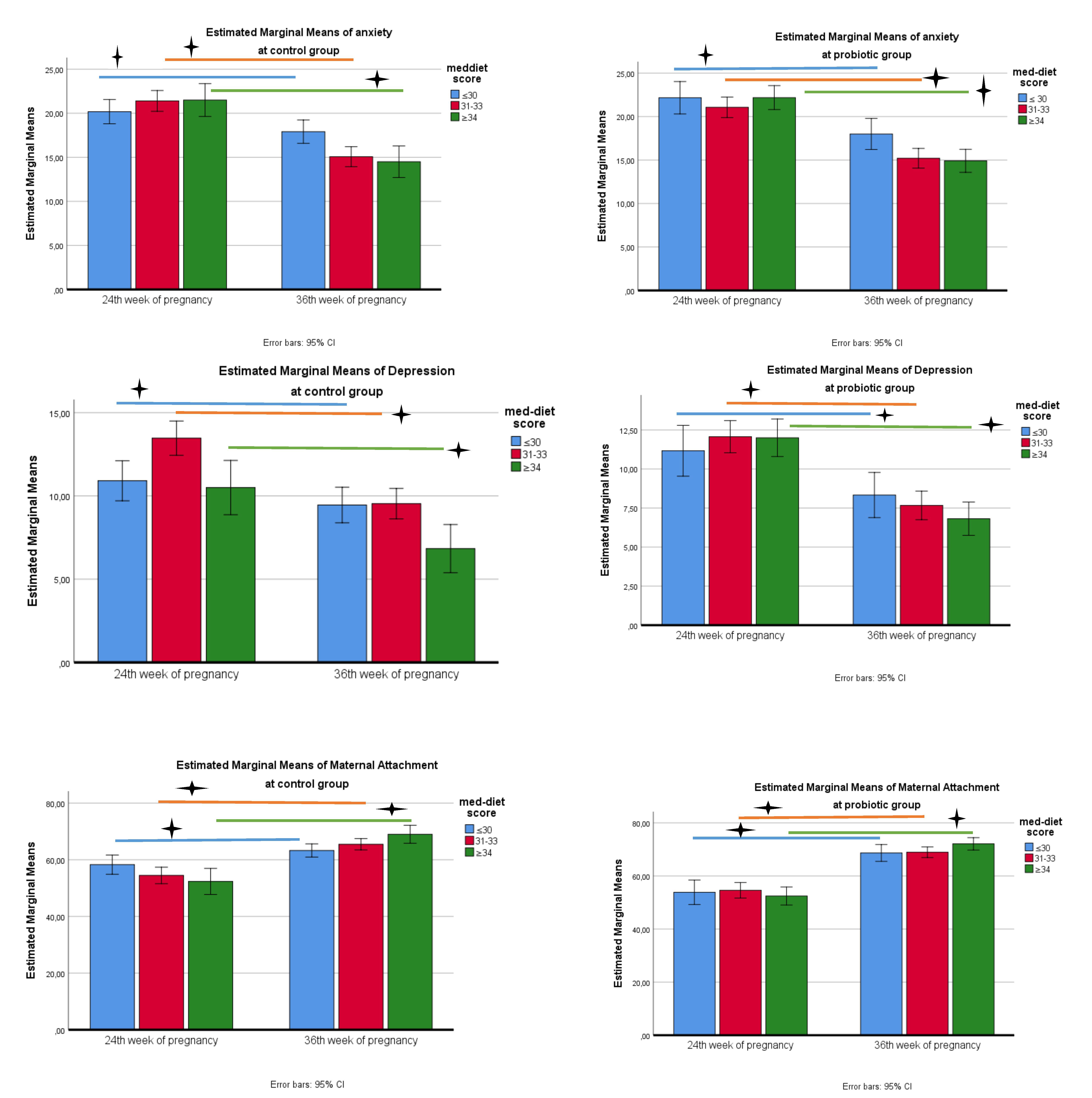

When the figure is examined, anxiety scale scores in the control group show a decrease between the pre-test and post-test in terms of compliance with the Mediterranean diet (Fig. 3). According to the results of the Bonferroni test, in which diet and time variables were compared together, a significant decrease was detected between the pre-test and post-test as the Mediterranean diet score increased (2.2 in the first quarter; 6.3 in the second quarter; 7 in the third quarter, a mean difference was detected, p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Change in anxiety, depression and attachment scale scores in probiotic and control groups. 🟄, p

There is no significant difference between the groups’ pre-test and post-test scores on the depression scale (F(1;58) = 0.844; p

| Source of Variance | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effect | |||||||

| Probiotic | 2698 | 1 | 2698 | 0.844 | 0.362 | 0.014 | |

| Med-diet score classification | 27,987 | 2 | 13,994 | 4376 | 0.017 | 0.131 | |

| Error | 185,487 | 58 | 3198 | ||||

| Interactive Effect | |||||||

| Time | 355,404 | 1 | 355,404 | 508,574 | 0.898 | ||

| Time+probiotic | 8708 | 1 | 8708 | 12,461 | 0.177 | ||

| Time+med diet score classification | 26,131 | 2 | 13,065 | 18,696 | 0.001 | 0.392 | |

| Time+med diet score classification+probiotic | 1851 | 2 | 0.929 | 1324 | 0.274 | 0.044 | |

| Error | 40,532 | 58 | 0.699 | ||||

A significant difference was found between the participants’ pre-test and post-test scores (F(1;58) = 508.574; p

The common effect of being in different groups and factors showing measurement at different times on the depression score of the participants was not found to be significant (F(2;58) = 1324; p

When the figure is examined, the depression scale scores in the control group show a decrease between the pre-test and post-test in terms of adaptation to the Mediterranean diet (Fig. 3). According to the results of the Bonferroni test, in which diet and time variables were compared together, a significant decrease was detected between the pre-test and post-test as the Mediterranean diet score increased (mean difference was determined as 1.45 in the first quarter; 3.9 in the second quarter; 3.6 in the third quarter, p

There is no significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores of the groups’ attachment scale (F(1;58) = 1542; p

| Source of Variance | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effect | |||||||

| Probiotic | 23,255 | 1 | 23,255 | 1542 | 0.219 | 0.026 | |

| Med-diet score classification | 3764 | 2 | 1882 | 0.125 | 0.883 | 0.004 | |

| Error | 874,739 | 58 | 15,082 | ||||

| İnteractive Effect | |||||||

| Time | 5,117,553 | 1 | 5,117,553 | 305,991 | 0.841 | ||

| Time+probiotic | 200,762 | 1 | 200,762 | 12,004 | 0.001 | 0.171 | |

| Time+med diet score classification | 277,540 | 2 | 138,770 | 8297 | 0.001 | 0.222 | |

| Time+ med diet score classification+ probiotic | 63,681 | 2 | 31,840 | 1904 | 0.158 | 0.062 | |

| Error | 970,023 | 58 | 16,725 | ||||

A significant difference was found between the participants’ pre-test and post-test scores (F(1;58) = 305.991; p

The common effect of being in different groups and measuring at different times on the participants’ maternal attachment score was not found to be significant (F(2;58) = 1904; p

When the figure is examined, attachment scale scores in the control group show an increase between the pre-test and post-test in terms of adaptation to the Mediterranean diet (Fig. 3). According to the results of the Bonferroni test, in which diet and time variables were compared together, a significant increase was detected between the pre-test and post-test as the Mediterranean diet score increased (mean difference was determined as 5 in the first quarter; 11 in the second quarter; 16.6 in the third quarter, p

Table 7 includes data on the correlation between Mediterranean diet scores and scale scores. The data in Table 7 show that there is a weak negative correlation between Mediterranean diet scores and pregnancy anxiety and depression scale scores of all participants at 24 and 36 weeks. However, there is a significant positive correlation between their Mediterranean diet scores and maternal attachment scores (p

| Diet score | Pregnancy anxiety | Maternal attachment | Depression scale | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Group | |||||

| Diet score | - | –0.241 | 0.313 | –0.472 | |

| Pregnancy anxiety | –0.241 | - | –0.311 | 0.579 | |

| Maternal attachment | 0.313 | –0.311 | - | –0.271 | |

| Depression scale | –0.472 | 0.579 | –0.271 | - | |

| Probiotic supplementation Group | |||||

| Diet score | - | –0.433 | 0.471 | –0.601 | |

| Pregnancy anxiety | –0.433 | - | –0.391 | 0.667 | |

| Maternal attachment | 0.471 | –0.391 | - | –0.477 | |

| Depression scale | –0.601 | 0.667 | –0.477 | - | |

Multiple regression analysis was performed to examine the prediction of depression risk based on the scores obtained from the Med-diet (referred to Mediterranean diet) scale. The results were presented in tables and interpreted. The findings were interpreted at a 95% confidence interval and significance levels of 0.05 and 0.01. In the regression analysis, the model included the diet score, EPDS, PrAS and MAAS mean scores. The significance values for EPDS, PrAS and MAAS were p = 0.001, p = 0.004 and p = 0.003, respectively. In the model used, the EPDS and PrAS variables negatively predicted the Med-diet score at a significant level, while MAAS predicted it positively (p

| Model | R | R2 | Adjusted R square | B | SH | p | |

| Fixed | 0.890 | 0.792 | 0.784 | 41.108 | 1.172 | 0.000 | |

| EPDS | –0.852 | 0.250 | –0.577 | 0.001 | |||

| PrAS | –0.323 | 0.166 | –0.328 | 0.004 | |||

| MAAS | 1.102 | 0.356 | 0.783 | 0.003 |

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PrAS, Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Scale; MAAS, Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale.

The findings of our study once again emphasize the Mediterranean diet. After the 12-week intervention, there was no significant difference between the probiotic group and the control group, and the fact that there was a significance in the pre-test-post-test scale scores in both groups shows that the Mediterranean diet applied to all participants was effective on depression, anxiety and maternal attachment during pregnancy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting the effect of probiotic supplementation on depression and maternal attachment in GDM. In the present randomized controlled trial, newly diagnosed women with GDM receiving probiotic supplementation with a medical nutrition therapy following the Mediterranean diet for 12 weeks improved depression and anxiety levels and additionally provided lower gestational weight gain. Also, a one-unit improvement in the Med-diet score resulted in a decrease in depression score of 0.57 units, a decrease in anxiety score of 0.3 units, and an increase of 0.78 units in maternal attachment.

Studies have investigated the anxiety levels of pregnant patients with GDM, indicating that 60.8% of women with GDM may experience mild or higher levels of anxiety [49, 50]. One study reported that the incidence of stress and depression in GDM patients was 3.79 times higher than normal pregnant patients [51]. In particular, higher levels of anxiety were noted in the first weeks after diagnosis (around week 24–28). There are studies showing a decrease in anxiety and depression conditions through controlled lifestyle changes (diet and physical activity), regular antenatal follow-up, blood sugar monitoring, social and psychological support and family assistance [52, 53, 54]. Also, there are studies indicating an increase in anxiety levels [55, 56]. The present study found a reduction in anxiety and depression levels at week 36. At this point, we suggest that the diet treatment applied to all participants was effective. We also believe that previous studies have ignored the effect of sedentary life on depression and anxiety in women who were advised to rest due to some complications during pregnancy. For this reason, we aimed to ensure homogenization in physical activity and did not include participants with sedentary physical activity in the study. We also did not include pregnant women with poor sleep quality in the study. Additionally, there is an increase in the MAAS binding score at the 36th week. Low levels of depression and anxiety in the mother are associated with increased attachment to the baby.

Gut microbiota can influence the physiological, behavioral and cognitive functions of the brain. Research has been conducted on the brain-gut axis as well as the effects of probiotics on brain behaviors [57, 58]. In a randomized controlled trial involving 40 participants with major depressive disorder, the active intervention group of 20 patients showed a significant decrease in BMI scores after eight weeks compared to the placebo group [59]. The optimal strain combinations, intervention period and host factors have lead to differences in the results of probiotic research. We chose a probiotic containing bacterial strains known to be effective on depression and anxiety. Since taking it with different foods may have an impact on effectiveness and absorption, we informed the participants in the probiotic group that they should take the probiotic orally with 100 mL of water. The purpose of including women with a body mass index between 18.5 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2 in our study was because the effect of probiotic intervention will be different in obese and thin women.

Although the current review demonstrated that probiotics do not have significant beneficial effect on depression or anxiety, considering that it is a pioneering study on probiotic supplementation in GDM, these findings should be considered preliminary [60, 61]. Furthermore, the limitations imposed on prepregnancy BMI and physical activity factors among the participants to minimize differences in energy and nutrient requirements in the dietary intervention were designed to better focus on the outcome of probiotic efficacy. A higher score of Mediterranean diet in the group receiving probiotics after the 12-week intervention suggests that probiotic supplementation may have an impact on diet motivation and adherence.

To optimize the impact of potential problems on depression, sleep problems, stressful events, and physical activity were monitored and homogenization was achieved between groups. Routine post-obstetric interviews and the establishment of nutritional therapy for GDM were effective in recruitment rates. To our knowledge, there is no other publication examining the effect of probiotic supplementation on anxiety, depression and maternal attachment in individuals with GDM.

Exclusion of participants using insulin in women with gestational diabetes resulted in a relatively small sample size (because the use of insulin may affect the results of the study). Therefore, our results should be confirmed and replicated in future studies. The scales used in this study are screening-only tools, but not diagnostic instruments. Due to the impact of depression and GDM on inflammatory pathways, mental health parameters like cortisol, serum total testosterone, CRP, TAC, GSH, and MDA levels would have been more useful to examine. Also, since the host affects the probiotic effect, better design trials in which basal intestinal bacteria are analyzed are needed.

In GDM patients, the Mediterranean diet quality had a significant negative relationship with depression and anxiety, and a positive relationship with maternal attachment. The group receiving probiotic supplementation had lower scores of depression and anxiety and lower gestational weight gain. However, the Mediterranean diet score was higher in the probiotic group at week 36. Further well designed randomized controlled trials with longer supplementation durations are needed for a stronger assessment of probiotic supplementation on maternal and fetal long-term mental health.

All data points generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and there are no further underlying data necessary to reproduce the results.

FBKB, SK and AT designed the research study. FBKB and SK performed the research. FBKB carried out the intervention. AT analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical approval was given by the Eastern Mediterranean University Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee (ETK00-2022-0273). All participants gave written informed consent and the research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.