1 Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, 610041 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

2 Key Laboratory of Birth Defects and Related Diseases of Women and Children, Sichuan University, Ministry of Education, 610041 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

3 Department of Clinical Medicine, School of Queen Mary, Nanchang University, 330006 Nanchang, Jiangxi, China

Abstract

Prenatal hyperandrogenism, characterized by elevated androgen levels during pregnancy, has significant multisystem impacts on offspring health. This review systematically examines the effects of prenatal hyperandrogenism on the cardiovascular, metabolic, reproductive, and behavioral health of offspring. By analyzing existing research, this review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the long-term health impacts of prenatal hyperandrogenism, offering insights for clinical management and prevention of related diseases.

A comprehensive search was performed in PubMed database with the key words: “hyperandrogenemia and child”, “hyperandrogenemia and offspring”, “androgen excess and child”, “androgen excess and offspring”, “prenatal hyperandrogenism”, “prenatal androgen excess”, and a combination of these terms to find quality articles published from 1995 to 2024.

Elevated prenatal androgen levels disrupt normal fetal development, leading to long-term consequences such as cardiovascular dysfunction, including hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy, and metabolic abnormalities such as insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. It has a significant impact on the long-term health of the offspring’s reproductive system, with potential links to conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Furthermore, prenatal hyperandrogenism is associated with increased risks of neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and anxiety.

Elevated prenatal androgen levels disrupt normal fetal development, leading to long-term cardiovascular, metabolic, reproductive, and neuropsychiatric disorders. The underlying mechanisms involve hormonal regulation, placental function, oxidative stress, gene expression alterations, and metabolic programming. Further research is needed to develop effective interventions to mitigate these adverse effects.

Keywords

- prenatal hyperandrogenism

- offspring health

- cardiovascular dysfunction

- metabolic syndrome

- reproductive disorders

Hyperandrogenism or hyperandrogenemia refers to medical conditions marked by abnormally high levels of androgens circulating in the body [1]. In the United States, the overall prevalence of hyperandrogenism in females is 19.8%, with significant variation across different age groups, racial/ethnic backgrounds, and metabolic characteristics [2]. The primary conditions associated with hyperandrogenism in reproductive-aged women are polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and ovulatory dysfunction, with PCOS affecting an estimated 10% to 13% of women in this age group [3]. Additional causes of androgen excess include congenital adrenal hyperplasia, adrenal tumors, differences in racial backgrounds. During pregnancy, factors such as luteoma, placental aromatase deficiency, and fetal congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) can also lead to gestational hyperandrogenism [4].

Hyperandrogenism has widespread and profound effects on women’s health. This condition manifests not only as simple hirsutism, sometimes without obvious biochemical features, but can also lead to pronounced virilization. Its symptoms and signs include those affecting the pilosebaceous unit (PSU), such as hirsutism, acne, and alopecia, as well as those affecting the female reproductive system, including amenorrhea and infertility [5]. Additionally, hyperandrogenism is a precursor to serious cardiovascular issues, such as hypertension, microvascular disease, and dyslipidemias, as well as other metabolic disorders, such as type 2 diabetes [6].

In addition to causing systemic and multi-organ effects on the mother, prenatal hyperandrogenism has widespread and profound impacts on the offspring. Epidemiological studies have established that the foundation for chronic diseases in adulthood is laid early in life [7, 8]. The developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) hypothesis suggests that unfavorable intrauterine conditions cause changes in an organism’s developmental pathway as an adaptive mechanism to prepare for an expected postnatal environment [9]. Prenatal hyperandrogenism is a typical example of an intrauterine condition that can negatively affect the developmental programming of the fetus. Hormones influence fetal growth directly by acting on genes and indirectly by affecting placental growth, fetal metabolism, and/or the production of growth factors and other hormones by the feto-placental tissues [10]. It disrupts the fetal endocrine environment and developmental processes, leading to various health issues in the offspring, such as growth and developmental disorders, metabolic dysfunction, and neuropsychiatric conditions. Therefore, investigating the effects of prenatal hyperandrogenism on the health of offspring, especially its widespread impacts across multiple systems and generations, is crucial for understanding and intervening in these conditions, providing a foundation for further research and clinical practice.

This review aims to systematically discuss the multisystem effects of prenatal hyperandrogenism on the health of offspring, with a particular focus on the development and function of the cardiovascular, metabolic, and reproductive systems. By comprehensively analyzing existing research findings, we hope to reveal the potential long-term health impacts of prenatal hyperandrogenism on offspring and provide scientific evidence for clinical management and prevention of related diseases.

Hyperandrogenism first manifests its impact on offspring during the fetal period, as abnormally elevated androgen levels significantly affect fetal growth and development. A prospective observational study in Caucasian women found that elevated maternal testosterone levels at weeks 17 was associated with lower birth weights and lengths. Accordingly, an increase in maternal testosterone levels from the 25th to the 75th percentile was associated with a decrease in birth weight by 160 g (95% confidence interval (95% CI): 29–290 g) [11]. Animal studies have also demonstrated the impact of elevated androgen levels on intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). In sheep, prenatal androgen exposure reduced body weights and heights of newborns from both sexes and chest circumference of females. Prenatal androgen exposed female neonates exhibit catch-up growth in the 2–4 months postpartum period, a phenomenon not observed in male neonates, which may increase future health risks, including obesity and metabolic syndrome [12]. Study in rats has also shown a dose-dependent reduction in birth weight of offspring exposed to high prenatal testosterone [13]. To explore the reasons, gestational testosterone exposure advances placental differentiation, initially helping to maintain placental efficiency. However, as pregnancy progresses, this advanced differentiation becomes insufficient to meet the high demands of the growing fetus, leading to IUGR and low birth weight, particularly in female offspring [14]. During different stages of gestation, prenatal androgen exposure induces changes in the expression of pro-inflammatory genes, antioxidant genes, and angiogenic genes, resulting in increased placental lipid accumulation, collagen deposition, and enhanced oxidative and nitrative stress, culminating in placental insufficiency [15]. Prenatal testosterone exposure leads to decreased fetal luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion and pituitary weight, as well as altered levels of gonadotropin regulators, with these effects being prevented by flutamide co-treatment, indicating direct androgen action during fetal development [16]. In summary, excessive testosterone significantly and persistently impacts fetal development and postnatal health by directly affecting placental differentiation and altering key hormonal and developmental processes.

Prenatal hyperandrogenism has a profound impact on the long-term health of offspring’s reproductive systems. The most pronounced effects occur in the external genitalia. Offspring exposed to prenatal hyperandrogenism can exhibit a spectrum of phenotypic outcomes, ranging from normal external genitalia in both male and female offspring to ambiguous genitalia specifically in female offspring. Fetal CAH and maternal luteoma are the most common causes of masculinization of the reproductive tract in female offspring [17, 18], whereas this has not been reported in PCOS. Anogenital distance (AGD) refers to the distance between the anus and the genitalia. It is commonly used as a marker to assess prenatal androgen exposure. Currently, evidence indicates that maternal PCOS affects AGD in male fetuses, but the impact on female fetuses remains controversial [19, 20]. Small-sample studies confirmed that the AGD in female offspring of PCOS mothers is longer, as evidenced by neonatal measurements and fetal ultrasound [20, 21]. Another large-scale prospective cohort study found that the AGD of offspring born to mothers with PCOS was similar to that of the control group at 3 months of age [19]. The differing results between the two studies may be attributed to differences in sample health status, body mass index (BMI), ethnic background, maternal smoking habits, and the impact of age on AGD measurements. PCOS may influence the AGD of offspring, but due to the current inconsistencies in research results, the exact extent and mechanisms of this impact still require further investigation.

For male offspring, while androgens play a critical role in male sexual differentiation, study indicates that maternal androgen excess has some impact on the reproductive axis. Research using prenatally androgenized mice found no significant effects on the reproductive axis, including LH pulse characteristics, daily sperm production, plasma testosterone, and anti-Müllerian hormone levels [22]. However, prenatal testosterone supplementation did affect puberty onset and behavior in male rats. Study found that prenatally androgenized male rats exhibited delayed puberty onset, increased aggressive behavior, and altered sexual preference in adulthood [23]. Additionally, maternal androgen excess significantly affects the sexual behavior of male mouse offspring, leading to sexual dysfunction [24].

For female offspring, prenatal hyperandrogenism is significantly associated with the development of PCOS [25]. Animal study first discovered that monkeys exposed to a high androgen environment prenatally may develop polycystic ovaries, high serum LH concentrations, and insulin resistance at puberty [26]. Human study showing excessive maternal or fetal androgen production may exhibit a phenotype resembling PCOS [27] whereas androgens within the normal range do not directly program PCOS in the offspring [28]. Excessive prenatal testosterone exposure activates postnatal follicular growth and impairs androgen synthesis in adult small antral follicles, affecting a wide range of gene expressions in the follicular theca, which may contribute to the development of polycystic ovarian syndrome [29]. Prenatal hyperandrogenism significantly affects ovarian lipid metabolism and steroidogenesis. Study has shown that prenatally hyperandrogenized rats exhibit altered lipid and hormonal profiles, and changes in steroidogenesis and ovarian lipid metabolism in adulthood [30]. In androgenized fetal sheep, research found serious disruptions in follicle development and steroidogenesis, with evidence of precocious primordial follicle formation and changes in the expression of steroidogenic enzymes and androgen receptors [31]. Further research revealed that prenatal androgen exposure increases LH pulse frequency in pubertal female rats and causes changes in the expression of related genes such as neurokinin B (NKB) and leptin receptor (LepR) before and during puberty. These changes may lead to long-term reproductive and metabolic dysfunctions, including anovulation, hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and hyperinsulinemia [32].

Perinatal hyperandrogenism also significantly affects female uterine function. Study found that exposure to different doses of testosterone propionate in rats altered uterine responsiveness to estradiol, showing abnormal stimulation of uterine tissue growth [33]. Additionally, excessive perinatal androgen exposure leads to long-term changes in the expression of steroid receptors, apoptosis, and cell proliferation in the uterus, potentially affecting normal uterine function in adulthood [34].

In conclusion, androgen excess has different effects on male and female offspring besides external genitalia appearance. In male offspring, excessive prenatal androgen exposure has a minimal impact on the reproductive axis but may lead to delayed puberty, increased aggressive behavior, and altered sexual preference, with the underlying mechanisms still requiring further investigation. In contrast, prenatal androgen exposure significantly increases the risk of PCOS in female offspring. It disrupts follicle development, ovarian lipid metabolism, and steroidogenesis, causing changes in related gene expressions in the hypothalamus and significantly affecting uterine function. These disruptions ultimately lead to reproductive dysfunctions in adulthood.

Prenatal hyperandrogenism has profound impacts on the cardiovascular health of offspring. Increasing research evidence suggests that maternal hyperandrogenism may increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases in the offspring during adulthood through mechanisms such as prenatal programming. These effects manifest as cardiac hypertrophy, hypertension, and sex-specific health issues.

In human studies, it has been found that high maternal androgen levels during pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases in offspring. For example, a study demonstrated that daughters of women with PCOS who have normal weight and are non-hirsute exhibit higher cardiovascular risk in adulthood, including elevated 24-hour, daytime, and nighttime diastolic and mean arterial pressures [35]. Another study indicated that female offspring of mothers with high levels of maternal androgens have a significantly increased risk of metabolic syndrome (MetS) and hypertension in adulthood, whereas male offspring do not show significant effects [36].

Multiple animal studies have also explored the impact of maternal

hyperandrogenism on the cardiovascular health of offspring. Prenatal

hyperandrogenism leads to cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction by inhibiting fetal

cardiomyocyte proliferation and maturation. It can induce cardiac hypertrophy in

adult female rats through enhanced protein kinase C delta (PKC

The effects of prenatal hyperandrogenism exhibit significant sex differences. Studies indicate that the cardiovascular impacts of hyperandrogenism are more pronounced in female offspring. For instance, female offspring show higher risks of cardiac hypertrophy and hypertension in adulthood [35, 36, 37, 39]. In contrast, male offspring are also affected but to a lesser extent [36, 44, 46]. These sex-specific effects may be related to differences in hormone levels and signaling pathways.

Prenatal hyperandrogenism affects offspring cardiovascular health through

multiple mechanisms. Research has shown that hyperandrogenism can inhibit

cardiomyocyte proliferation through retinoblastoma (RB)-mediated cell cycle

arrest [42] and induce cardiac hypertrophy via enhanced PKC

The discovery of the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) [47] lineage reveals that the cardiovascular and reproductive systems may share a common embryonic origin, providing a potential mechanistic explanation for the synergistic effects of androgen exposure on cardiovascular and reproductive health. Understanding these interconnections can provide scientific evidence for clinical interventions to mitigate the long-term adverse effects of androgen exposure on offspring health.

Prenatal hyperandrogenism is significantly associated with the development of insulin resistance and glucose regulation abnormalities in offspring. When examining glucose metabolism in children born to mothers with hyperandrogenism, a significantly increased risk of pre-diabetes was found [48]. Long-term population studies have found that maternal hyperandrogenism increases the risk of pre-diabetes mellitus (Pre-DM) in both male and female offspring during adulthood [49, 50]. As for animal models, experimentally induced gestational androgen excess disrupted glucose regulation in rhesus monkeys and their female offspring, leading to glucose intolerance and decreased insulin sensitivity [51]. In sheep models, prenatal testosterone exposure resulted in insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia in female offspring during puberty and adulthood [52, 53].

Hyperandrogenism also has significant impacts on the liver and lipid metabolism of offspring. Prenatal high androgen levels lead to the development of fatty liver in adult offspring and affect liver metabolic pathways and receptor expression [54]. It increases fatty acid levels and inflammatory markers in the liver, changes cholesterol content and fatty acid oxidation capacity [55, 56]. Disrupted fatty acid metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction (such as reduced oxidative phosphorylation and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis, altered mitochondrial transport, and impaired mitophagy), along with elevated hepatic reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and early signs of liver fibrosis in male offspring were also observed in prenatal hyperandrogenism offspring, suggesting relevance to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) progression [57].

Considering the alterations in the cardiovascular system and metabolism observed in offspring affected by hyperandrogenism, the emergence of metabolic syndrome is unsurprising. Research suggests that heightened maternal androgens elevate the likelihood of metabolic syndrome in adult female offspring, particularly evident through dyslipidemia, increased insulin resistance and raised blood pressure [50, 54]. Research using a dehydroepiandrosterone-induced polycystic ovary syndrome model also shows that female offspring exhibit increased body weight, higher body fat content, and reduced energy expenditure in adulthood [58]. Regarding sex differences, higher maternal androgen levels are significantly associated with an increased risk of metabolic syndrome in adult female offspring, whereas no significant difference is observed in male offspring [36]. Furthermore, prenatal androgen exposure affects not only the first generation but also the second generation through maternal or paternal pathways, resulting in abnormalities in growth, weight, and glucose metabolism [59]. In summary, prenatal androgen exposure has profound and potentially multigenerational effects on metabolic syndrome in offspring.

Mechanistic studies have revealed the underlying pathways through which prenatal

androgen exposure leads to metabolic dysfunction. Prenatal androgen exposure

first alters gene expression in oocytes, increasing levels of insulin-like growth

factor 2 (IGF2), mitotic checkpoint protein (Bub3), and serine/threonine-protein

kinase (Nek4), while decreasing DNA-methyltransferase 3 alpha (DNMT3a)

expression, which subsequently leads to insulin resistance and abnormalities in

hepatic gluconeogenesis and lipid metabolism [48, 60]. Additionally, prenatal

androgen exposure significantly impacts pancreatic function by reducing sirtuin 3

expression in the pancreas, impairing

Prenatal exposure to high levels of androgens during pregnancy may increase the incidence of neuropsychiatric disorders in offspring. High levels of maternal androgens during pregnancy can cross the placenta and enter the fetus, affecting fetal brain development [64, 65]. This impact can result in lasting changes in behavior and neuropsychiatric function by altering gene expression and brain structure [66]. Hyperandrogenemia may lead to neuropsychiatric disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [67, 68, 69], attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [69], anxiety disorders [64, 70], and Tourette’s disorder and chronic tic disorders (TD/CTD) [69]. Several population studies have demonstrated a correlation between hyperandrogenemia and a heightened risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in offspring. Studies have found that children of mothers with PCOS have a significantly increased risk of developing ASD [66, 67, 68, 69]. Additionally, these children are at higher risk for pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs) [71]. An Israeli study indicated that the incidence of ASD is higher among children of mothers with PCOS, and this risk is related to maternal cardiovascular, metabolic, and fertility factors [66]. Another nationwide study in Sweden, which controlled for familial genetic factors, further demonstrated the impact of androgen exposure on the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in offspring [69].

Using RNA sequencing and chromatin immunoprecipitation combined with direct sequencing, a study in human neural stem cells differentiated from embryonic stem cells identified androgen-regulated genes enriched in ASD related pathways, suggesting that prenatal androgen exposure may influence ASD risk through these gene expressions [72]. Animal studies have provided detailed mechanistic insights, demonstrating that androgens influence behavior by altering gene expression and brain structure. Research has shown that mice exposed to high levels of androgens during pregnancy exhibit significant anxiety-like behavior in adulthood, and this behavior is associated with changes in gene expression in the amygdala and hypothalamus [64, 70]. Additionally, by administering low doses of letrozole to pregnant rats to simulate a hyperandrogenic environment, study has found that the offspring exhibit autism-like behaviors in social interaction and communication [65]. These studies indicate that the effects of androgens on brain development are likely mediated through the regulation of gene expression and changes in brain structure.

Hyperandrogenemia’s impact on neuropsychiatric disorders in offspring also shows significant gender differences. Female offspring exposed to prenatal hyperandrogenism are more likely to develop ASD, anxiety disorders, and PDDs. This may be due to the influence of high androgen levels during pregnancy on the development of specific brain regions in female fetuses, such as changes in gene expression in the amygdala and hypothalamus [64, 66]. Additionally, changes in social and communication abilities are also significant [73]. Although male offspring are also affected by prenatal androgen exposure, the overall increase in risk is slightly lower compared to female offspring. Male offspring primarily exhibit attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and anxiety disorders [69, 70].

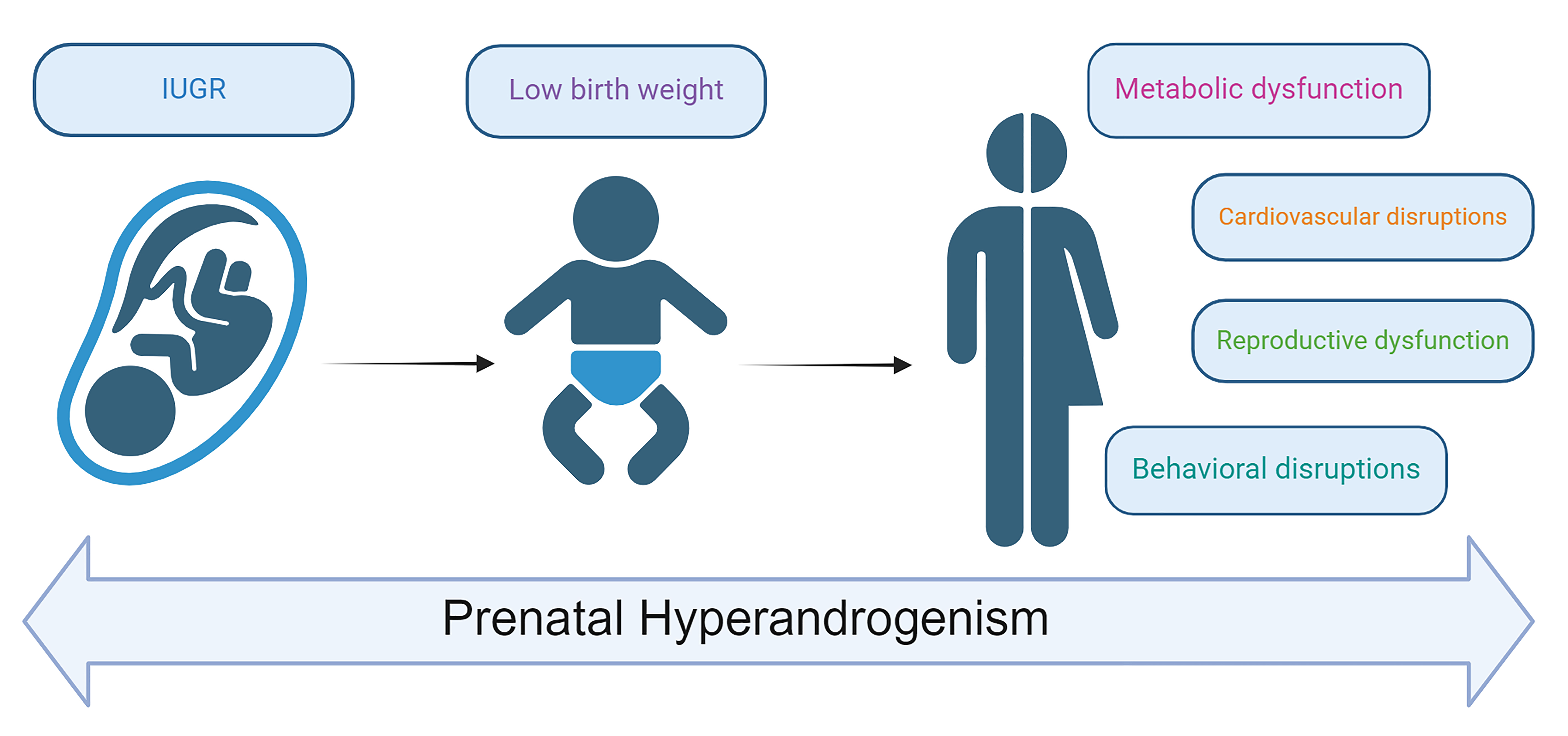

This review explores the profound and multisystem effects of prenatal hyperandrogenism on offspring health. Studies indicate that elevated androgen levels have significant and enduring impacts on offspring growth and development, reproductive function, cardiovascular health, metabolic function, and behavioral health (Fig. 1; Table 1, Ref. [11, 12, 13, 23, 24, 27, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40, 42, 43, 45, 48, 49, 51, 52, 53, 54, 60, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 71]). Prenatal hyperandrogenism disrupts fetal development and causes persistent, widespread issues across multiple systems postnatally. The impact of maternal hyperandrogenism is extensive and complex, affecting offspring through intricate mechanisms such as compromised placental function, altered gene expression, disrupted metabolic programming, and hormonal dysregulation. Elevated androgen levels can lead to placental insufficiency, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses, affecting fetal growth and development and resulting in long-term health issues across multiple systems. Changes in androgen metabolism and signaling pathways not only cause insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome but also affect cardiovascular health, increasing the risks of cardiac hypertrophy and hypertension. Furthermore, the impact of androgens on fetal gene expression and developmental programming can lead to reproductive and neurological dysfunctions, manifesting as PCOS, ASD, and ADHD in adulthood.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Multisystem health consequences of prenatal hyperandrogenism in offspring. IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction.

| System | Subject | Gender and relative impact | Main findings |

| Growth and developmental disorders | Human | Both; female more evident | Reduced birth weight, restricted height growth [11] |

| Sheep | Both; female more evident | Reduced birth weight and heights, rapid weight gain during infancy in female [12] | |

| Rats | Both; female more evident | Reduced birth weight, significant masculinization in female [13] | |

| Reproductive system | Human | Both; female more evident | PCOS-like phenotype in female offspring [27] |

| Mouse | Both; female more evident | Slight decrease in mounting ability in male; significant impairment in sexual behavior in female [24] | |

| Rats | Male | Delayed puberty onset, increased aggressive behavior, altered sexual preference, and reduced plasma testosterone levels in adulthood [23] | |

| Cardiovascular system | Human | Both; female more evident | Elevated arterial pressures [35, 36] |

| Rats | Female | Cardiac hypertrophy [37]; hypertension [45] | |

| Mice | Both | Cardiac hypertrophy [42], compromised cardiac function in adult offspring [43] | |

| Sheep | Both; female more evident | Cardiac hypertrophy and pathological left ventricular remodeling [38, 40] | |

| Metabolic System | Human | Both | Prediabetes [48, 49]; metabolic Syndrome [36] |

| Monkey | Female | Glucose intolerance and decreased insulin sensitivity [51] | |

| Sheep | Both; female more evident | Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia [52, 53] | |

| Mice | Both | Insulin resistance, and alteration in hepatic gluconeogenesis and lipid metabolism [60] | |

| Rats | Female | Dyslipidemia and hepatic steatosis, features of the metabolic syndrome [54] | |

| Behavioral System | Human | Both; female more evident | Increased risk of autism spectrum disorder [66, 67, 68, 69]; attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, Tourette’s disorder and chronic tic disorders [69] |

| Pervasive developmental disorders [71] | |||

| Rats | Both; female more evident | Anxiety-like behavior [64]; autism spectrum disorder and impaired social interaction [65] |

PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome.

Sexual dimorphism is a key factor, with androgens typically having a more pronounced impact on female offspring compared to males. Female offspring are more likely to exhibit cardiac hypertrophy and hypertension, possibly due to differences in hormone levels and signaling pathways. They are also more prone to developing metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in adulthood, whereas male offspring show milder symptoms. In terms of behavioral health, prenatal hyperandrogenism has a more significant impact on female offspring, who are more susceptible to ASD and anxiety disorders, while male offspring are mainly affected by ADHD and anxiety disorders. Sexual dimorphism may arise from the differing impacts of androgens on hormonal levels, gene expression, signaling pathways, and developmental mechanisms during fetal development in females and males.

The limitations of this review mainly lie in the fact that most studies are based on animal models, which may not fully reflect human conditions. Additionally, some studies have small sample sizes, which may affect the generalizability of the results. Future research should focus on several areas: (1) expand sample size and conduct large-scale population studies: to enhance the generalizability of research findings, future studies should include larger and more diverse populations. Large-scale epidemiological studies can validate results from animal models and provide insights specific to human populations. Additionally, research should strengthen the exploration of human mechanisms to reveal how prenatal androgen exposure affects human health at the molecular and cellular levels. These mechanistic studies will help better understand the long-term effects of androgen excess on humans and provide a scientific basis for developing effective intervention strategies. (2) Investigate gender differences in androgen exposure: currently, most studies concentrate on female offspring, with many exclusively targeting them. However, existing data also indicate that male offspring can be significantly affected by excessive prenatal androgen exposure, highlighting the need to further explore the mechanisms of gender differences. Although research on male offspring is relatively limited, study has shown that they also face notable health issues. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the effects of androgen excess on offspring, future studies should include larger sample sizes and controls for male offspring. This will help uncover the differential impacts of androgen excess on both sexes and provide a solid foundation for developing more effective prevention and intervention strategies. Evaluate the Effectiveness of Interventions: while current research focuses on the impacts of high androgen levels on offspring, there is limited exploration of how interventions might mitigate these effects. Evaluating the effectiveness of various intervention strategies in reducing the adverse impacts of prenatal androgen exposure is essential. This includes testing different therapeutic approaches and preventive measures to determine their impact on improving offspring health. These studies will help uncover the fundamental causes of sex-specific differences, leading to the development of more effective interventions to prevent and mitigate the adverse effects of prenatal hyperandrogenism on offspring.

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGpt-3.5 in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation was performed by WC. The first draft of the manuscript was written by DL and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. QZ: project development, manuscript editing. DL: project development, manuscript writing. WC: manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us while writing this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Qian Zhong is serving as one of the Guest editors of this journal. We declare that Qian Zhong had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Maria E. Street.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.