1 Discipline Inspection Committee, Chongqing Medical and Pharmaceutical College, 401331 Chongqing, China

2 School of Public Health, Chongqing Medical University, 401331 Chongqing, China

Abstract

Studies have suggested that medical students experience higher perceived stress, poorer overall health, and a higher incidence of depression, anxiety, and burnout than non-medical students. This study compared sleep quality and mental health (depression, anxiety, and stress) between Chinese medical and non-medical students, and analyzed their distribution across different academic years and sexes, thereby providing a theoretical basis for targeted mental health interventions.

Online questionnaires were distributed across 18 provincial administrative regions in China, covering 15 medical colleges and 55 non-medical universities. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) were used to assess mental health and sleep quality.

A total of 11,972 valid responses were obtained, including 5619 medical students and 6353 non-medical students. We found that medical students exhibited higher psychological stress but did not show significantly worse sleep quality, with some indicators demonstrating a “stress-sleep decoupling” phenomenon. Mental health indicators showed a “peak-trough-peak” pattern across academic year: stress peaked in the second year, improved briefly in the fourth year, and peaked again in the fifth year, accompanied by a synchronous deterioration in sleep quality. Sex-based comparisons indicated that females experienced more pronounced mental stress and sleep problems.

Overall, medical students have poorer mental health, consistent with previous studies. However, the observed “stress-sleep decoupling” phenomenon suggests that the structured environment of medical education may buffer the relationship between stress and sleep. The absence of such decoupling in the fifth year, along with the high-risk characteristics observed in female students, provides key targets for educational practice. This study recommends incorporating “stage-specific and differentiated” support strategies into higher education policies, such as dynamic, grade-based psychological support, sleep hygiene courses targeted at female students, and emotion regulation training. These measures aim to promote the transformation of educational policies from “uniform management” to “precision support”.

Keywords

- medical students

- mental health

- non-medical students

- sleep quality

Sleep disorders and mental health problems have emerged as significant challenges in global public health, exerting substantial effects on individual well-being and social development (Chattu et al, 2018). Epidemiological studies have indicated that nearly one-third of the general population experiences insomnia symptoms (e.g., difficulty falling asleep and/or maintaining sleep), 4%–26% reported excessive daytime sleepiness, and 2%–4% suffered from obstructive sleep apnea (Ohayon, 2011). Currently, approximately 301 million people worldwide have anxiety disorders, and 280 million have depressive disorders, with adolescents aged 10–19 accounting for ~14% of cases (World Health Organization, 2022). Mental health problems are the primary cause of disability among 15–19-year-olds, constituting 45% of their overall disease burden (The Lancet, 2017). Notably, a bidirectional association exists between sleep disorders and mental health problems (Meyer et al, 2024). Individuals with insomnia are 10 times more likely to exhibit clinical depression and 17 times more likely to show anxiety than are non-insomniacs (Taylor et al, 2005). A meta-analysis of 21 longitudinal studies showed baseline insomnia doubles the risk of developing depression during follow-up (Baglioni et al, 2011).

This bidirectional interaction between sleep disorders and mental health problems is particularly prominent among college students. University life, a critical transitional period from adolescence to adulthood, is marked by drastic changes in lifestyle and behavioral patterns—such as living independently away from home, increased social and extracurricular activities, constantly shifting social circles, and rising academic pressures—making college students a high-risk group for sleep problems and psychological disorders. The prevalence of sleep disorders reaches 33% (Deng et al, 2021), and this issue worsened significantly during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, with the prevalence rising to 45.96% (Jahrami et al, 2022). Meanwhile, these lifestyle changes and psychological stressors have fostered unhealthy behaviors like smoking and excessive alcohol consumption (Taylor et al, 2013; Wang and Bíró, 2021). Sleep problems not only impair cognitive functions (e.g., attention, memory) and emotional stability (Maheshwari and Shaukat, 2019) but also negatively affect academic performance (Lawson et al, 2019) and increase depressive susceptibility (Lu et al, 2019).

Among students, medical education’s intensity—heavy coursework, intensive clinical clerkships/internships (Jahrami et al, 2020), and research training (Memon et al, 2021)—exposes medical students to severe challenges (Niño García et al, 2019). A meta-analysis of 57 studies (25,735 medical students) revealed that 52.7% have poor sleep quality, which was highly correlated with anxiety/depression (Rao et al, 2020); sleep-deprived medical students had

International studies have primarily been conducted in Saudi Arabia (Al-Khani et al, 2019), Greece (Eleftheriou et al, 2021), and Dubai (Meer et al, 2022), with limited explanatory power for population characteristics within the Chinese education system. However, it is generally acknowledged that increased stress deteriorates sleep quality, showing a significant positive correlation between the two (Alwhaibi and Al Aloola, 2023; Huang et al, 2024). However, the uniqueness of medical education may introduce variations to this relationship; medical students receive systematic training in health knowledge, and their perception of stress and practice of sleep hygiene may differ from those of non-medical students. Whether such professional backgrounds can lead to the “stress-sleep decoupling” phenomenon—sleep quality does not deteriorate in synchrony with high stress—remains underexplored. Relevant studies in China have been mostly single-institution or small-sample surveys (Wu et al, 2022), lacking nationwide data support, systematic comparisons with non-medical students, investigations into education stage-specific characteristics, and exploration of the potential “decoupling” phenomenon. Based on this, the present study, through a nationwide multi-center, cross-sectional survey, focused on addressing the following questions: Are there significant differences in sleep quality and mental health between the two groups? How do mental states and sleep quality vary across grade (year in school) and sexes? Do the “stress-sleep” association patterns exhibit specificity in the two groups?

This study used a cross-sectional design. An online questionnaire was administered to college students in China via the Wenjuanxing platform, from September 2024 to January 2025, with questionnaires distributed through official university channels. Using a stratified-cluster sampling method, the survey covered 70 universities across 18 provincial administrative regions, including 15 medical colleges and 55 non-medical universities. The specific distribution of regions and the number of universities are shown in Table 1. Notably, this survey was conducted during the post-pandemic normalization of COVID-19 prevention and control. Although potential residual effects of previous pandemic experiences (e.g., long-term impacts on sleep patterns or stress responses) on participants could not be entirely ruled out, the nationwide multi-center sampling strategy—covering diverse regions and educational institutions—minimized biases in comparing group differences between medical and non-medical students. Thus, the core analysis of inter-group disparities remained robust despite these contextual factors, which were acknowledged but not the focus of the present study. All participants’ data were de-identified before retrieval. Privacy information was protected through encrypted storage and restricted access only to authorized members of the research team. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Chongqing Medical and Pharmaceutical College (Approval No.: KYLLSC20240922005) and strictly adhered to the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration.

| Region | Province | Total number of institutions | Number of medical universities | Number of non-medical universities |

| East China | Zhejiang | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| Jiangsu | 0 | 1 | ||

| Anhui | 0 | 1 | ||

| Fujian | 0 | 1 | ||

| South China | Guangdong | 13 | 1 | 8 |

| Hainan | 1 | 1 | ||

| Guangxi | 0 | 2 | ||

| Central China | Hunan | 9 | 3 | 5 |

| Henan | 0 | 1 | ||

| North China | Tianjin | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Beijing | 1 | 3 | ||

| Northwest China | Xinjiang | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| Shanxi | 0 | 1 | ||

| Southwest China | Chongqing | 28 | 3 | 21 |

| Sichuan | 1 | 1 | ||

| Guizhou | 2 | 0 | ||

| Northeast China | Heilongjiang | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Liaoning | 2 | 1 | ||

| Total | 70 | 15 | 55 |

All participants provided online informed consent prior to answering the questionnaire, which acknowledged potential risks and confidentiality measures of the study. The research team ensured data quality through IP-address restrictions and by monitoring response duration (estimated 10–20 minutes). A total of 12,090 initial questionnaires were collected. After excluding 118 invalid questionnaires due to severely unreasonable response time (

In addition to basic information (age, sex, university, grade, major), standard survey tools were used to measure core variables. Mental health was assessed using the DASS-21, a 21-item scale with three subscales (depression, anxiety, stress; 7 items each). Responses use a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never to 3 = always), with subscale scores

Sleep quality was evaluated using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The original PSQI scale was developed by (Buysse et al, 1989) and includes 18 self-rated and 5 observer-rated items, assessing seven components (subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, hypnotic use, daytime dysfunction) over the previous month. Scores range from 0 to 21, with

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R 4.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). First, normality tests (Shapiro-Wilk test) were conducted for continuous variables (DASS subscale scores, DASS total score, PSQI total score). Variables meeting normality were described by mean standard deviation, and independent samples t-tests were used. Since most continuous variables did not follow a normal distribution, they were described by median (interquartile range, IQR). Nonparametric tests were applied for group comparisons: the Mann-Whitney U test for two groups and the Kruskal-Wallis H test for multiple groups (by grade). Categorical variables were presented as frequency (%) and analyzed using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact probability test (when theoretical frequency

To explore the relationship between sleep quality and mental health, Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was used to assess the association strength between PSQI and DASS scores, as well as between sleep quality (PSQI score) and mental health indicators (DASS subscale scores and total score). All significance tests were two-tailed, and p

Significant differences in demographic characteristics were observed between medical and non-medical students. As shown in Table 2, chi-square tests indicated statistically significant differences in grade distribution (

| Variables | Medical student (Yes/No), n (%) | Total | Statistic | p | ||||

| No | Yes | 11,972 | ||||||

| 6353 (53.065%) | 5619 (46.935%) | |||||||

| Grade | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Freshman year | 3070 | 48.32% | 2339 | 41.63% | 5409 | |||

| Sophomore year | 2961 | 46.61% | 2396 | 42.64% | 5357 | |||

| Junior year | 227 | 3.57% | 505 | 8.99% | 732 | |||

| Senior year | 75 | 1.18% | 366 | 6.51% | 441 | |||

| Fifth year | 20 | 0.31% | 13 | 0.23% | 33 | |||

| Sex | 0.918 | |||||||

| Male | 2198 | 34.60% | 1939 | 34.51% | 4137 | |||

| Female | 4155 | 65.40% | 3680 | 65.49% | 7835 | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 180 | 2.83% | 279 | 4.97% | 459 | ||||

| 18 | 2314 | 36.42% | 1709 | 30.41% | 4023 | |||

| 19 | 2485 | 39.12% | 1952 | 34.74% | 4437 | |||

| 20 | 1041 | 16.39% | 1016 | 18.08% | 2057 | |||

| 21 | 226 | 3.56% | 396 | 7.05% | 622 | |||

| 22 | 71 | 1.12% | 201 | 3.58% | 272 | |||

| 23 | 19 | 0.30% | 56 | 1.00% | 75 | |||

| 24 | 17 | 0.27% | 10 | 0.18% | 27 | |||

| Depression score | ||||||||

| 0–9, Normal | 2553 | 40.19% | 2895 | 51.52% | 5448 | |||

| 10–13, Mild depression | 2331 | 36.69% | 1786 | 31.79% | 4117 | |||

| 14–20, Moderate depression | 1413 | 22.24% | 894 | 15.91% | 2307 | |||

| 21–27, Severe depression | 52 | 0.82% | 43 | 0.77% | 95 | |||

| 4 | 0.06% | 1 | 0.02% | 5 | ||||

| Anxiety score, n (%) | ||||||||

| 0–7, Normal | 1153 | 18.15% | 1137 | 20.23% | 2290 | |||

| 8–9, Mild anxiety | 1878 | 29.56% | 1513 | 26.93% | 3391 | |||

| 10–14, Moderate anxiety | 2759 | 43.43% | 2527 | 44.97% | 5286 | |||

| 15–19, Severe anxiety | 495 | 7.79% | 393 | 6.99% | 888 | |||

| 68 | 1.07% | 49 | 0.87% | 117 | ||||

| Stress score | ||||||||

| 0–14, Normal | 5468 | 86.07% | 4509 | 80.25% | 9977 | |||

| 15–18, Mild stress | 723 | 11.38% | 911 | 16.21% | 1634 | |||

| 19–25, Moderate stress | 151 | 2.38% | 190 | 3.38% | 341 | |||

| 26–33, Severe stress | 11 | 0.17% | 9 | 0.16% | 20 | |||

| 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | ||||

| DASS score | 0.982 | |||||||

| 21–38, Mild | 4691 | 73.84% | 4165 | 74.12% | 8856 | |||

| 39–52, Moderate | 1497 | 23.56% | 1309 | 23.30% | 2806 | |||

| 53–65, Severe | 138 | 2.17% | 120 | 2.14% | 258 | |||

| 27 | 0.42% | 25 | 0.44% | 52 | ||||

| PSQI | ||||||||

| Good sleep quality | 1026 | 16.15% | 1295 | 23.05% | 2321 | |||

| Mild sleep problems | 3515 | 55.33% | 3124 | 55.60% | 6639 | |||

| Moderate sleep disorders | 1717 | 27.03% | 1150 | 20.47% | 2867 | |||

| Severe sleep disorders | 95 | 1.50% | 50 | 0.89% | 145 | |||

n, number of samples; DASS, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Due to rounding adjustments for precision, the total percentages may not add up to exactly 100%.

In age distribution, medical students significantly dominated the

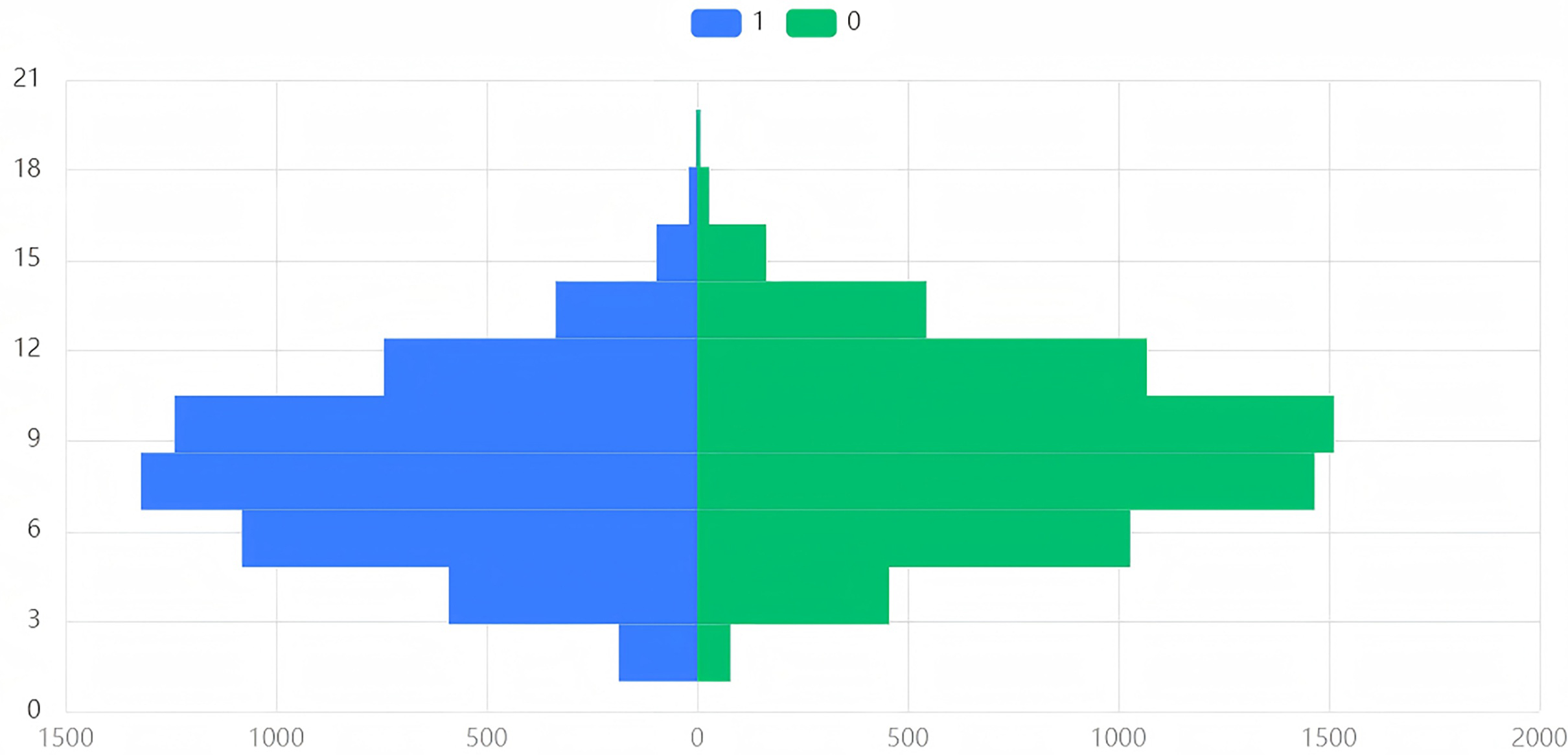

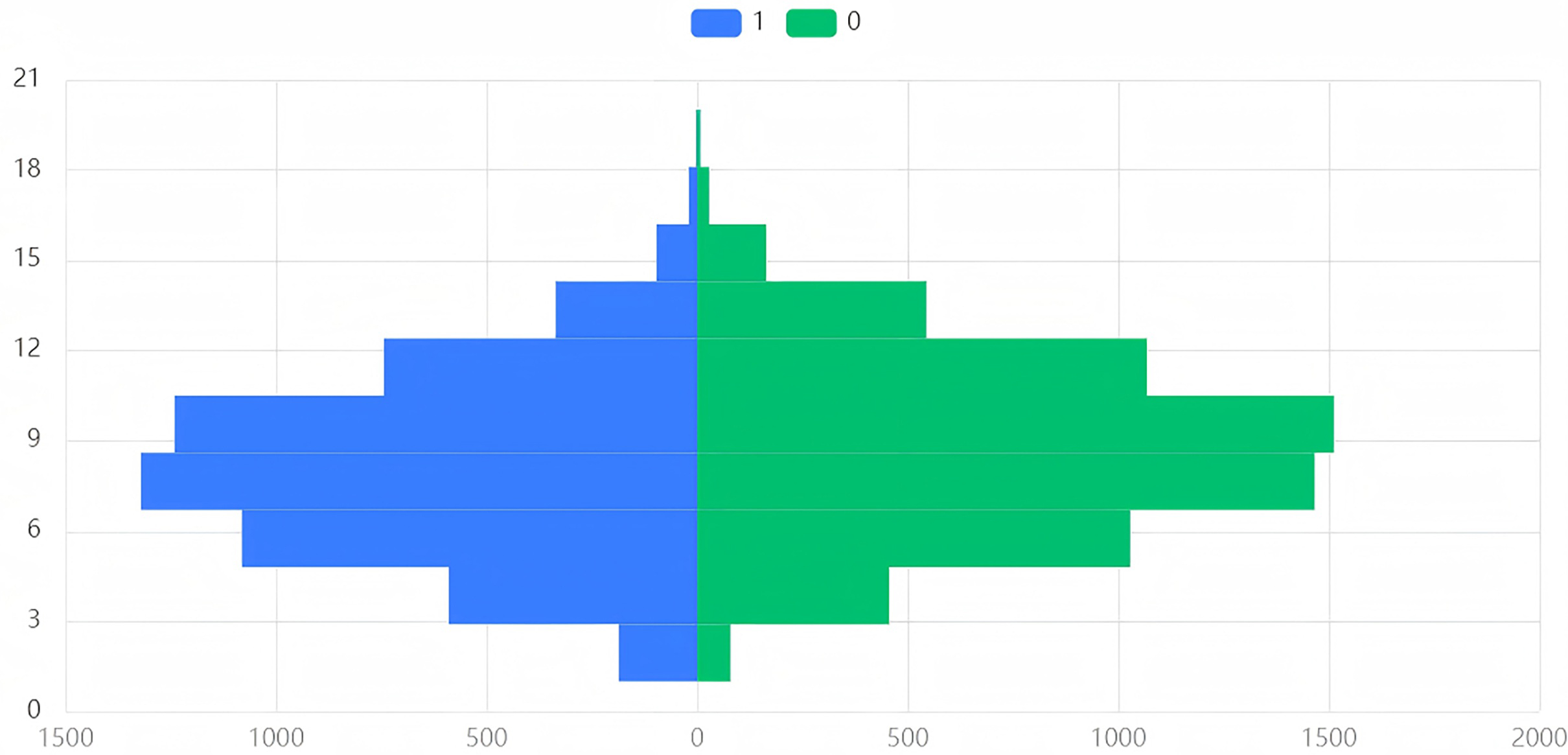

Mann-Whitney U test results showed that the DASS total score distribution in both groups approximated a pyramid, mostly concentrated at 20–30 points (Table 3 & Fig. 1). The median total DASS score for both groups was 31 (p = 0.094). The two groups were not significantly different, and the effect size was extremely small (Cohen’s d = 0.024) (Table 4), indicating that the overall level of psychological distress was similar in both groups. Medical students did not exhibit significantly higher overall distress than did non-medical students, though subtle differences existed in specific dimensions.

| Variable name | Score range | Medical student (Yes/No) | Total | |||

| No (n, %) | Yes (n, %) | |||||

| DASS Score | [21.0, 36.75) | 4355 | 68.55% | 3839 | 68.32% | 8194 |

| [36.75, 52.5) | 1833 | 28.85% | 1635 | 29.10% | 3468 | |

| [52.5, 68.25) | 146 | 2.30% | 128 | 2.28% | 274 | |

| [68.25, 84.0] | 19 | 0.30% | 17 | 0.30% | 36 | |

| Total | 6353 | 5619 | 11,972 | |||

| PSQI Score | [1.0, 5.75) | 1026 | 16.15% | 1295 | 23.05% | 2321 |

| [5.75, 10.5) | 3515 | 55.33% | 3124 | 55.60% | 6639 | |

| [10.5, 15.25) | 1717 | 27.03% | 1150 | 20.47% | 2867 | |

| [15.25, 20.0] | 95 | 1.50% | 50 | 0.89% | 145 | |

| Total | 6353 | 5619 | 11,972 | |||

Due to rounding adjustments for precision, the total percentages may not add up to exactly 100%.

| Variable name | Group | Sample size | Median | Standard deviation | Statistic | p | Median difference | Cohen’s d |

| DASS Score | medical students | 5619 | 31 | 9.055 | 17,533,032 | 0.094* | 0 | 0.024 |

| non-medical students | 6353 | 31 | 9.001 | |||||

| Total | 11,972 | 31 | 9.027 | |||||

| PSQI Score | medical students | 5619 | 8 | 3.121 | 15,474,682 | 0.000*** | 1 | 0.242 |

| non-medical students | 6353 | 9 | 3.078 | |||||

| Total | 11,972 | 8 | 3.120 |

***, * respectively represent the significance levels of 1%, 10%.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Comparison of the distribution of psychological distress levels (total DASS scores) between medical and non-medical students. Note: 1 = Medical students, 0 = Non-medical students, Y axis = n, X axis = DASS score.

Further comparison of DASS-21 subscales revealed (details in Table 2) the following results. Depression: non-medical students reported higher depressive symptoms (59.81% vs. 48.48%), possibly influenced by employment uncertainty. Anxiety: both groups showed high anxiety reporting rates (81.85% vs. 79.77%), with similar severe anxiety proportions (8.86% vs. 7.87%), suggesting universal academic stress. Stress: the prevalence of mild (11.38%) and moderate (2.38%) stress in non-medical students was lower than in medical students (16.21% and 3.38%, respectively); no extremely severe cases were found in either group. Although statistically non-significant, these trends held clinical implications: medical students experienced greater stress but slightly better depression outcomes.

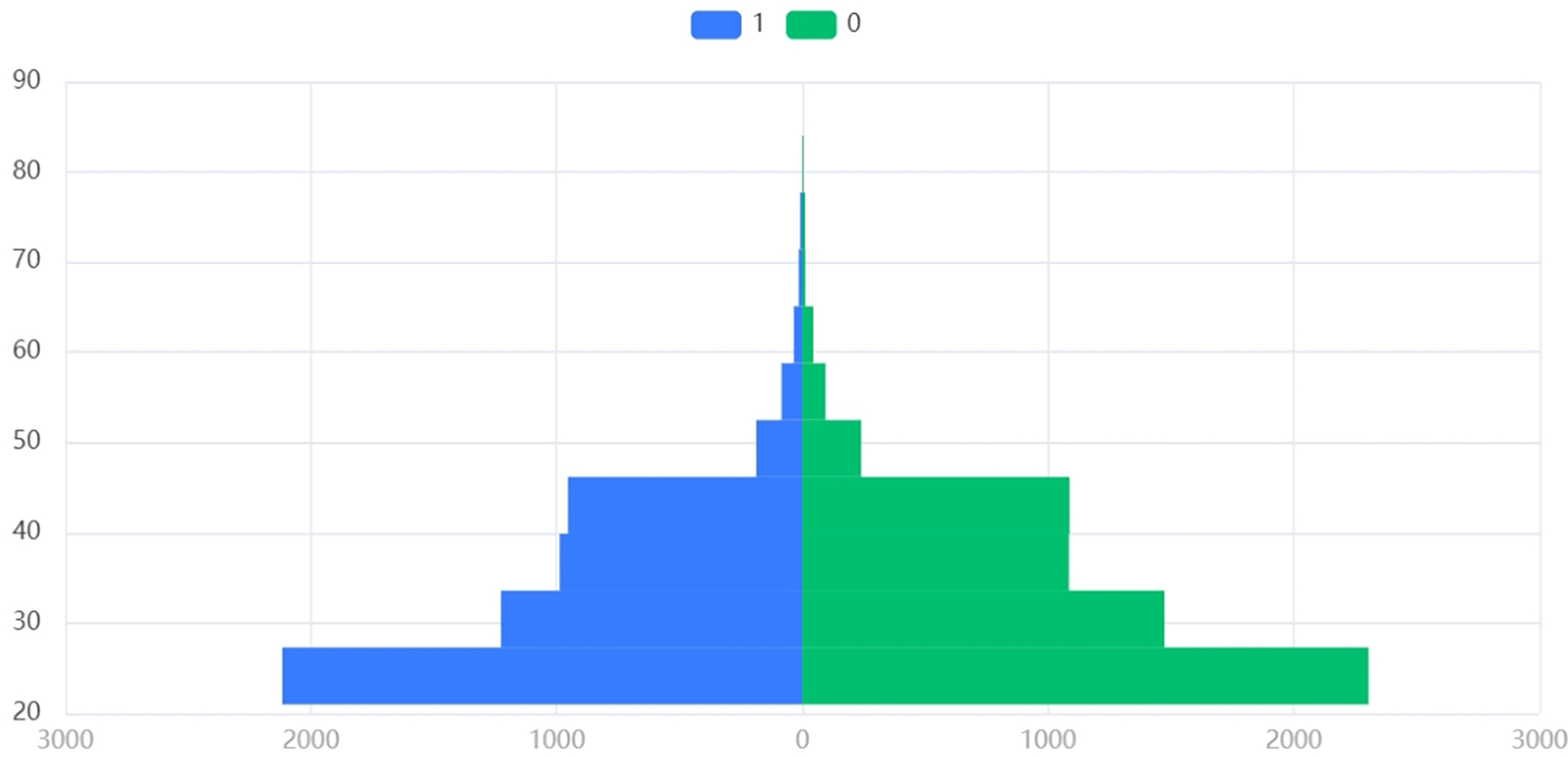

For sleep quality, medical students had a PSQI median of 8 vs. 9 for non-medical students, with a significant difference (p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Differences in the distribution of sleep quality (total PSQI scores) between medical and non-medical students. Note: 1 = Medical students, 0 = Non-medical students, Y axis = n, X axis = PSQI score.

Using sex as the grouping variable, results of the Mann-Whitney U test (Table 5) showed significant differences in both DASS total scores and PSQI total scores between males and females (all p

| Variable name | Group | Sample size | Median | Standard deviation | Statistic | p | Median difference | Cohen’s d |

| DASS Score | female | 7835 | 32 | 8.749 | 18,320,769.5 | 0.000*** | 3 | 0.171 |

| male | 4137 | 29 | 9.449 | |||||

| Total | 11,972 | 31 | 9.027 | |||||

| PSQI Score | female | 7835 | 9 | 3.109 | 18,103,507 | 0.000*** | 1 | 0.200 |

| male | 4137 | 8 | 3.101 | |||||

| Total | 11,972 | 8 | 3.120 |

***, respectively represent the significance levels of 1%.

As shown in Table 6, Kruskal-Wallis H tests comparing mental health (depression, anxiety, stress) and sleep scores across grades revealed significant grade effects (H values: 53.350–230.515, all p

| Analysis item | Grade | Sample size | Median | Standard deviation | Statistic | p | Cohen’s f |

| Depression score | 1 | 5409 | 10 | 3.011 | 169.705 | 0.000*** | 0.005 |

| 2 | 5357 | 10 | 3.287 | ||||

| 3 | 732 | 10 | 3.554 | ||||

| 4 | 441 | 9 | 3.032 | ||||

| 5 | 33 | 12 | 3.964 | ||||

| Total | 119,72 | 10 | 3.197 | ||||

| Anxiety score | 1 | 5409 | 9 | 2.893 | 180.030 | 0.000*** | 0.004 |

| 2 | 5357 | 10 | 3.116 | ||||

| 3 | 732 | 10 | 3.322 | ||||

| 4 | 441 | 9 | 2.949 | ||||

| 5 | 33 | 11 | 3.592 | ||||

| Total | 11,972 | 10 | 3.047 | ||||

| Stress score | 1 | 5409 | 11 | 3.193 | 230.515 | 0.000*** | 0.004 |

| 2 | 5357 | 12 | 3.432 | ||||

| 3 | 732 | 12 | 3.743 | ||||

| 4 | 441 | 10 | 3.324 | ||||

| 5 | 33 | 13 | 3.847 | ||||

| Total | 11,972 | 11 | 3.375 | ||||

| DASS score | 1 | 5409 | 29 | 8.497 | 217.812 | 0.000*** | 0.004 |

| 2 | 5357 | 33 | 9.224 | ||||

| 3 | 732 | 32 | 10.085 | ||||

| 4 | 441 | 28 | 8.799 | ||||

| 5 | 33 | 36 | 10.808 | ||||

| Total | 11,972 | 31 | 9.027 | ||||

| PSQI score | 1 | 5409 | 8 | 3.005 | 53.350 | 0.000*** | 0.002 |

| 2 | 5357 | 9 | 3.204 | ||||

| 3 | 732 | 8 | 3.170 | ||||

| 4 | 441 | 8 | 3.185 | ||||

| 5 | 33 | 9 | 3.249 | ||||

| Total | 11,972 | 8 | 3.120 |

***, respectively represent the significance levels of 1%; Cohen’s f represents the effect size, with the thresholds for small, medium, and large effect sizes being 0.1, 0.25, and 0.40.

Specifically, in terms of mental health, the stress level of sophomores showed the first significant peak: the median score of the DASS stress subscale for sophomores was 12, which is 1 point higher than that of freshmen. Additionally, 52.8% of sophomores scored

PSQI also fluctuated by grade but followed a different pattern than mental health indicators. Sophomores and fifth-year students had PSQI medians of 9 (vs. 8 for freshmen, juniors, and seniors), indicating poorer subjective sleep during high-stakes academic periods (sophomore year) and pre-graduation (fifth year). Notably, seniors showed reduced mental stress (DASS) but unchanged PSQI (median = 8), suggesting asynchronous mental health and sleep dynamics. This dissociation implies that sleep may be influenced by independent variables like internship schedules or behavioral habits, beyond psychological stress. In sophomore and fifth-year students, a bidirectional stress-sleep deterioration pattern emerged: academic/employment stress

The statistical results and trends of the aforementioned grade differences indicate that the dynamic impact of grade on college students’ psychology and sleep is characterized by “stage-specific fluctuations and interweaving of multiple factors”. There are statistically significant differences in mental health and sleep characteristics among students of different grades, which provides an important reference for understanding the stage-specific characteristics of the group. However, it should be noted that the effect sizes in some multiple-group comparisons were small, suggesting that this phenomenon may not have reflected strong individual correlations. Moreover, the independent impact of grade was limited; actual differences are also influenced by multiple moderating factors such as living habits, social support, and academic pressure. The clinical significance of the dynamic impact of grade on college students’ psychology and sleep needs to be comprehensively judged by combining the core stressors of each grade and group characteristics.

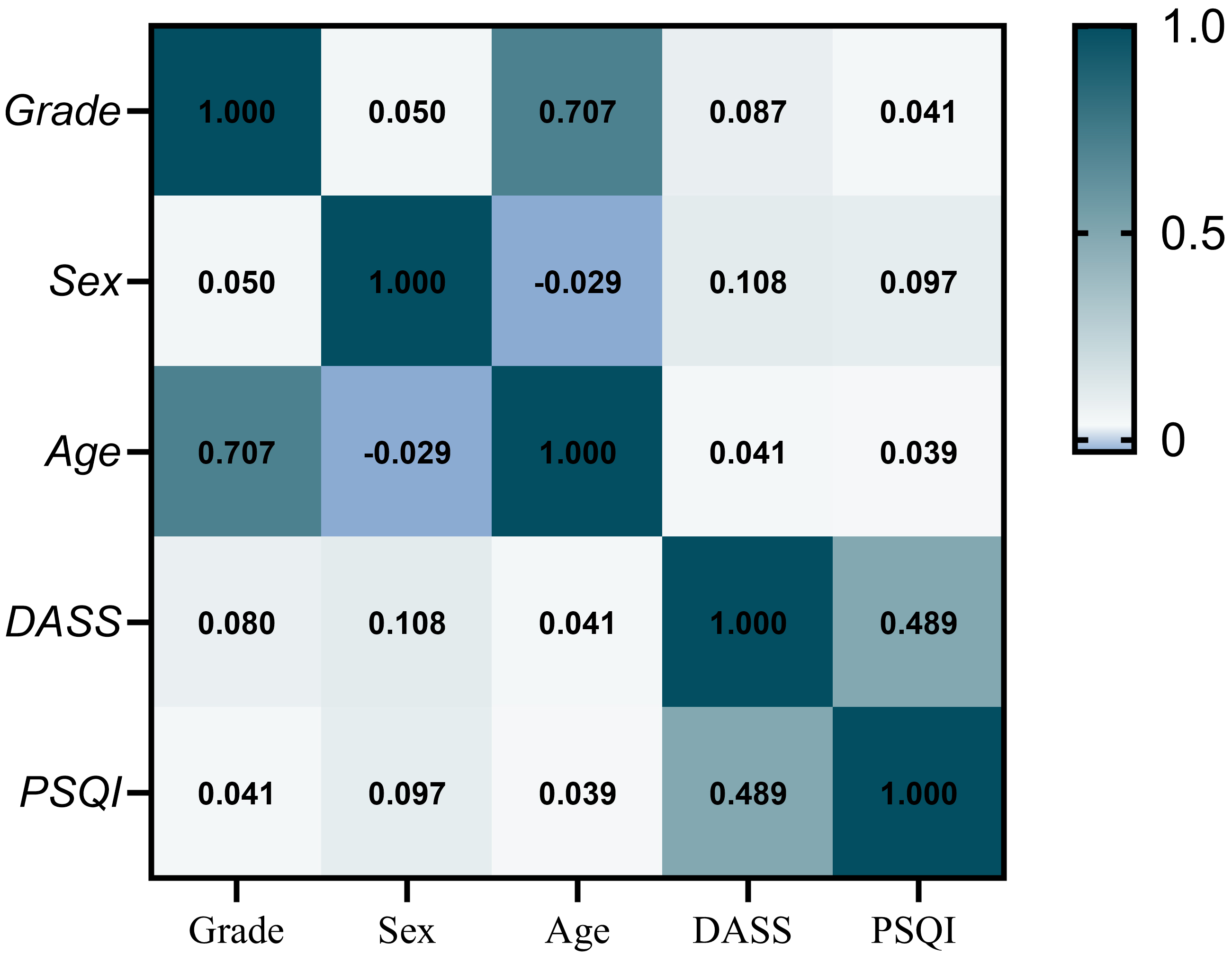

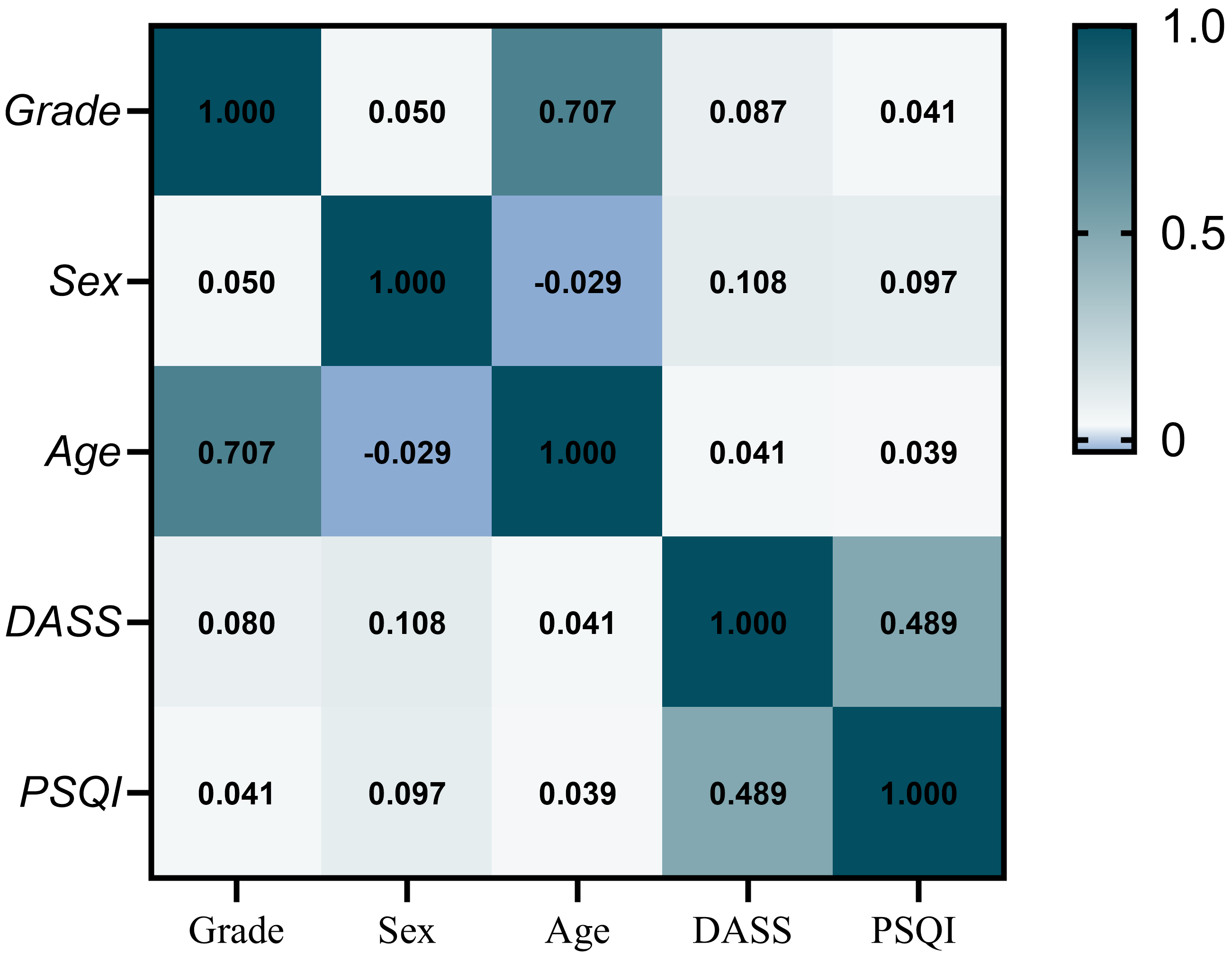

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were used to examine the association between PSQI total scores and DASS subscale scores (Fig. 3). The p-values for all pairwise correlations in this analysis are provided in Supplementary Material. All primary variables showed statistically significant pairwise correlations (p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Spearman correlation heatmap: Associations between mental health indicators, sleep quality, and demographic factors. Supplementary data tables with p-values for association analysis are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Contrary to our expectations and the common understanding in previous studies that “stress and sleep deteriorate synchronously” (Alwhaibi and Al Aloola, 2023; Huang et al, 2024), our study observed that although medical students had significantly higher DASS stress scores than did non-medical students (positive rate of the stress scale: 19.75% vs. 13.93%), their median PSQI total score was slightly lower (8 vs. 9). That is, a “stress-sleep decoupling” occurred in the medical student population: subjective sleep quality did not decrease with increased psychological stress, and some sleep indicators were even better than those of non-medical students. We should emphasize that because these were cross-sectional observational findings, this phenomenon reflected the association pattern at a specific time point, and cannot rule out the influence of unobserved variables (such as socioeconomic factors, technology use, social support scales, comorbidities, exercise, etc.), and requires verification of a causal relationship and mediating effects through longitudinal studies. Despite needing verification of its mechanism and stability, this phenomenon—observed in a large sample of Chinese medical students—suggests a unique stress-sleep association pattern in medical education, offering a new perspective for understanding sleep quality’s protective mechanisms in high-stress environments.

The strict and regular curriculum and clinical-rotation schedules in medical schools impose external constraints that objectively regulate sleep-wake cycles, potentially reducing common bedtime procrastination (Kroese et al, 2016). That helps stabilize circadian rhythms and avoid extreme sleep irregularities. Additionally, medical education integrates health management knowledge, leading to significantly higher health literacy among medical students than among students in other disciplines (Mullan et al, 2017; Rababah et al, 2019), particularly among clinical medicine students (Budhathoki et al, 2019). When experiencing sleep disturbances, they are more inclined to self-regulate (e.g., by reducing unnecessary late-night activities or napping during breaks). Thus, despite heavy academic loads, the “structural protection” of their environment and self-health awareness appears to mitigate the negative impact of stress on sleep.

By contrast, non-medical students lack such external constraints and health education, often sacrificing sleep to cope with academic pressures, leading to more pronounced sleep-quality decline. This suggests that university educators could adopt elements of medical education—such as strict sleep-wake management and sleep-health education—for non-medical students, e.g., promoting regular bedtimes, limiting late-night activities, to foster healthier sleep patterns. In addition, the PSQI should be incorporated into annual, routine, mental health screenings. A dynamically updated electronic archive of college students’ sleep and stress should be established to realize a closed-loop management process of “assessment-early warning-intervention”.

It is critical to note that the “stress-sleep decoupling” in medical students may partially mask underlying issues through behavioral compensation. To cope with high stress, medical students often adopt strategies like relying on caffeine, napping to compensate for sleep deprivation, or maintaining rigid schedules. Although these tactics may temporarily preserve cognitive function and academic efficiency, excessive caffeine intake and irregular napping can disrupt sleep architecture, leading to chronic sleep deprivation (Navarro-Martínez et al, 2020). The synchronous deterioration of sleep and mental health among fifth-year medical students indicates that decoupling has thresholds; when stress exceeds limits (e.g., graduation pressure, job competition), sleep becomes vulnerable. Thus, decoupling may represent a delayed or buffered impact rather than absence of stress-sleep association. Longitudinal studies tracking medical students into graduate training or careers are needed to verify long-term consequences, as initial decoupling might transition to coupled deterioration, unmasking hidden sleep issues in medical education.

Therefore, in medical education, it is necessary to provide additional psychological support for senior students, such as career guidance and stress-reduction courses, to help them smoothly go through the transitional period and prevent psychological problems caused by accumulated stress. Furthermore, we suggest attending to potential sleep-compensation behaviors among medical students and providing them with proper guidance, such as moderating caffeine consumption, avoiding accumulating sleep debt due to persistently staying up late, and conducting regular objective sleep assessments (e.g., polysomnography monitoring) to understand their actual sleep status, so as to prevent problems before they occur.

The present study revealed a “peak-trough-peak” fluctuation in mental health and sleep across grades, a non-linear pattern indicating that different academic years entail distinct stressors and adaptation tasks.

Sophomores exhibited a significant stress peak, confirming the “sophomore slump” (Webb and Cotton, 2019). In the second year, many students may be confronted with challenges such as a step-up increase in the difficulty of their major courses and the need to reposition themselves. Meanwhile, some universities carry out major diversion or selection in the second year, and students may encounter a “major commitment crisis”, that is, they may waver in their initial major choice due to the gap between their ideals and reality, academic pressure, or doubts about their career prospects (Yu et al, 2023). These factors interact to reduce self-efficacy, amplify self-doubt, and erode psychological resilience, triggering acute stress. Freshmen benefit from a “novelty buffer” in the new environment, whereas sophomores lose this protection amid escalating challenges, leading to the slump. This pattern appears in both medical and non-medical students, though medical sophomores may experience more severe stress due to core medical curricula and intensive knowledge acquisition.

To deal with this phenomenon, educators can take some intervention measures, such as setting up special psychological counseling courses in the sophomore year to help students adjust their unreasonable cognition and cultivate their ability to withstand pressure. It is necessary to balance the difficulty of examinations and evaluations appropriately in order to avoid overly undermining students’ confidence. The academic guidance and care from mentors for sophomore students should be strengthened to help them smoothly get through this adaptation stage.

The results of this study showed that the psychological stress of respondents in their fifth year of undergraduate study reached the peak among all grades. The essence of this is the superimposed effect of multiple stress sources. First, all graduates are facing the structural squeeze in the job market. According to the statistics of the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (2024), the number of college graduates in China in 2025 is expected to be 12.22 million, an increase of 430,000 over the previous year. Fierce competition causes severe employment pressure on college students, which in turn leads to unstable emotions and anxiety (Tu and Liu, 2025). Second, medical students also face the complex pressure specific to their profession. During the senior year, medical students are at a crucial stage of transition from campus to clinical or workplace settings. The source of their stress shifts from “academic competition” to “clinical responsibility and patient interaction”. They need to transform theoretical knowledge into clinical skills and independently complete high-risk tasks such as the collection of medical histories and the formulation of treatment plans. This process is often accompanied by “ability panic”. The impact of clinical decision-making responsibility on mental health significantly exceeds that of regular workload (Song et al, 2017). If there is a lack of sufficient support and preparation, individuals may find it difficult to bear, resulting in a rapid deterioration of mental health. Although the sample size of the fifth-year students in the present study was relatively limited (n = 33, 0.54%), this distribution difference was highly consistent with the characteristics of medical education stages. The low participation rate of fifth-year students in surveys due to clinical internships, job search preparations, and other factors is a common phenomenon in cross-sectional studies in the medical field (Al-Khani et al, 2019; Rababah et al, 2019). Nonetheless, the study results still showed the trend of “synchronous deterioration of stress and sleep quality” among fifth-year medical students, suggesting that the graduation season may be a high-risk window for medical students’ mental and sleep health. This study provided preliminary evidence for subsequent targeted interventions for the graduating class.

Based on the above findings, we recommend that (a) education authorities and medical colleges establish a systematic psychological support system for graduating medical students, including implementing a progressive clinical-competency training program with phased increases in clinical responsibilities; (b) establish a regular tutor-communication mechanism to promptly address confusion during internships; and (c) integrate group psychological supervision sessions once every two weeks into internship rotations in combination with mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) training, so as to balance clinical competency development and mental health maintenance (An et al, 2022). These measures will help medical students smoothly transition from school to clinical practice and prevent mental health problems caused by maladaptation.

This study confirmed that female college students exhibit poorer mental health and sleep quality than do male students, consistent with prior research: women have 1.4 times higher insomnia susceptibility than men (Zhang and Wing, 2006), nearly double the likelihood of poor sleep quality (Madrid-Valero et al, 2017), and higher rates of depression, anxiety, and neuroticism (Sung and Kim, 2020; Kajonius et al, 2025).

These sex differences may relate to females’ stress processing styles and hormonal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle (Lok et al, 2024). The HPA axis is more sensitive to stress in females, with more frequent or prolonged stress-hormone secretion. This heightened physiological sensitivity means that females experience more intense or enduring anxiety in identical stress contexts, predisposing them to sleep disorders and anxiety-related symptoms (Kudielka and Kirschbaum, 2005). Cyclic estrogen fluctuations and their interaction with melatonin may also disrupt sleep-rhythm stability. For example, sleep quality declines during the luteal phase in some women (Baker and Driver, 2007). Additionally, gendered coping styles play a role: females tend to express emotions and seek help, which may inflate self-reported stress and sleep problems due to greater symptom awareness and reporting bias.

Conflicts in social role expectations impose additional stress on females. Sex inequality remains deeply entrenched in the labor market. As reported by the United Nations (2023), the sex gap in leadership positions persists; at the current pace of progress, the next generation of women will still spend 2.3 more hours daily on unpaid care and household labor than will men. This inequality manifests itself not only in time allocation but also in economic income. Globally, women earn just 51 cents for every dollar earned by men, a wage gap that exacerbates financial insecurity and amplifies psychological burdens. Additionally, sex disparities in labor force participation are striking: only 61.4% of prime-working-age women engage in the labor market, compared to 90% of men. These differences reflect both career advancement barriers for women and societal stereotypes about female roles, as women are often expected to assume more family responsibilities. In China, although higher education expansion has narrowed sex gaps in educational attainment, women face relatively fewer labor market opportunities than do men post-expansion, potentially reinforcing traditional gendered family arrangements (Si, 2022).

Integrating the above bio-psycho-social factors helps explain why female college students are disadvantaged in mental health and sleep. To address this disparity, educators and healthcare providers should design targeted support programs for female students within mental health services, such as emotion-management groups and female career development forums, to alleviate stress from role conflicts. For sleep interventions, female students should be encouraged to adopt good sleep hygiene practices, reduce blue-light exposure before bedtime, and seek professional help when necessary (e.g., psychotherapy or sleep clinics).

This study has some limitations that should be noted when interpreting the results. First, restricted causal inference: the cross-sectional design only reflects the association patterns between stress and sleep (e.g., the “decoupling” phenomenon) at a specific time point, and cannot verify dynamic causal relationships or long-term stability. Subsequent longitudinal studies are needed for further validation. Second, sample representativeness and heterogeneity: medical sub-disciplines (e.g., clinical medicine vs. basic medicine) were not differentiated, which may mask inter-subdiscipline differences; the fifth-year sample accounted for only 0.54%, potentially underestimating the actual stress levels of senior students. Future studies should optimize this issue through targeted sampling. Third, measurement and selection biases: reliance on subjective scales (PSQI, DASS-21) may lead to underestimation of real problems due to medical students’ cognitive tendencies related to health knowledge; survival bias may weaken the assessment of cumulative effects of stress/sleep problems. Subsequent research can be improved by combining objective monitoring (e.g., polysomnography) and longitudinal designs.

Based on a nationwide survey of 11,972 college students, this study revealed the similarities and differences in the relationship between sleep and mental health between medical students and non-medical students, as well as their distribution characteristics across different grades and sexes. We recommended that educational administrative departments and colleges formulate differentiated support strategies targeting different majors, grades, and genders; establish a longitudinal monitoring system for sleep and mental health to dynamically track group trends; and strengthen psychological counseling and sleep management at key stages to create a supportive educational environment.

The data used in this study have been anonymized and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The questionnaires and scales employed in this research were either authorized for use or obtained from public sources. For access to the raw data or copies of the measurement instruments, please contact the corresponding author.

ZS was responsible for conceptualization, project administration, manuscript drafting, and revision. TW participated in conceptualization, investigation, and original manuscript drafting. XZ and JW each made contributions to data curation, data analysis, and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Chongqing Medical and Pharmaceutical College (Approval No.: KYLLSC20240922005) and was conducted in strict accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study.

Not applicable.

This study was funded by Project of the 14th Five-Year Plan for Educational Science of Chongqing in 2025 (K25ZG3030226); 2025 Humanities and Social Sciences Projects of Chongqing Medical and Pharmaceutical College (YGZSK2025207); 2024 Healthy School Research Project of Chongqing School Health Association (WXC2024013).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used DeepSeek V3 in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31084/BP44349.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.