1 School of Management, Xuzhou Medical University, 221004 Xuzhou, Jiangsu, China

2 Medical Affairs Department, The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, 221006 Xuzhou, Jiangsu, China

3 Research Center for Psychological Crisis Prevention and Intervention of College Students in Jiangsu Province, Xuzhou Medical University, 221004 Xuzhou, Jiangsu, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

The family plays a vital role in adolescents’ development, shaping their self-concept, which in turn affects their social adaptation, academic achievement, and overall well-being. This study examines the impact of family care on college students’ self-concept and explores how emotions mediate this relationship.

A cluster random sampling survey was conducted among 1058 college students from three universities. This questionnaire included the general sociodemographic characteristics of college students, as well as the Wallace Self-Concept Scale (WSCS), the Family Adaptation, Partnership, Growth, Affection, and Resolve (APGAR) Index, and the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS). Data analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0.

Family care, emotions, and self-concept varied based on gender, only-child status, and residence. Boys showed higher levels of positive emotion and self-concept than girls. Only children experienced more positive emotion and received more family care than non-only children, while urban residents reported more family care than rural residents. Family care was positively correlated with self-concept and positive emotion (r = 0.086, 0.078; p < 0.01) and negatively correlated with negative emotion (r = –0.065, p < 0.001). Positive emotion fully mediated the relationship between family care and self-concept (β = 0.795, p < 0.001); negative emotion partially mediated this relationship (β = –0.551, p < 0.001).

This study shows a strong link between family care and college students’ self-concept, with emotions playing a mediating role in this connection. The findings offer both theoretical insights and practical suggestions for supporting mental health and personal growth. It recommends strengthening cooperation between home and school and increasing family support to encourage positive emotions and enhance self-concept among college students.

Keywords

- family care

- self-concept

- positive and negative emotions

- college students

Contemporary college students are in the “new adulthood” stage (Boyes et al, 2023). They are vulnerable to influences such as interpersonal sensitivity (Xu et al, 2022; Mi et al, 2025), learning adjustment (Kan and Xu, 2024), and adverse life events (Liu et al, 2025), which can lead to mental health issues caused by cognitive problems, including symptoms of depression and anxiety (Li et al, 2022b). Self-concept is a predictor of mental health (Rao and Tamta, 2015), and individuals with high self-concept tend to have better mental health compared to those with low self-concept (Lee and Kim, 2022). The family, as a key area of socialization, has a significant impact on the development of self-concept among adolescents and young adults (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006). Especially in the context of East Asian family culture, family members are interdependent, and family care culture has a significant impact on an individual’s behavior, cognitive processes, and interpersonal interactions (Yang, 2024). Therefore, studying how family care impacts self-concept is especially important in understanding college students’ mental health.

Self-concept, as the foundation of personality development, plays a vital role in psychological well-being and behavioral regulation during personal growth (Rogers, 1951; Pérez-Sánchez et al, 2024; Vega-Díaz et al, 2023). Building a stable self-concept system is essential and represents a key developmental challenge for teenagers (Erikson, 1968; Cheng et al, 2021). As early as the beginning of the 20th century, American social psychologist Cooley introduced the concept of “mirror self”. He believed that the formation of self-concept is achieved through an individual’s perception of how others view them, thus enabling the development of self-awareness. Subsequently, another American social psychologist, Mead, further proposed that individuals constantly adjust their behavior based on feedback from others and form their identities through interactive life experiences (Wang, 2023). Early researchers believed that the general self-concept was at the highest level and could be divided into academic self-concept and non-academic self-concept (Shavelson et al, 1976). Harter (2012) proposed and confirmed that the self-concept of children and adolescents is a multi-dimensional and hierarchical structure. A recent study has shown that adolescents’ self-concept develops through a continuous transformation from concrete, simple, and unified to abstract, complex, and diverse (Crone et al, 2022). It does not have a positive linear relationship with age; instead, it follows a curving trend, reaching its lowest point in junior high school (Tamm et al, 2024). Recently, the dynamic nature of self-concept and its dependence on circumstances have gained increased attention. Self-concept is not only a systematic recognition and evaluation of one’s abilities, traits, values, and social roles (Shavelson et al, 1976) but also continuously adapts through social comparisons and domain-specific feedback loops (Eccles and Wigfield, 2020). Eccles et al. (2023) identify supportive assessments from family and teachers as critical external factors in the ongoing adjustment of self-concept. Studies have shown that academic self-concept significantly influences students’ motivation and achievement through social comparisons (Murn and Steele, 2020) and mediates the relationship between achievement goals and students’ perceptions of feedback (Guo and Xu, 2025). Another study indicates that vocational self-concept clarity can effectively predict proactive career behaviors among higher vocational students (Zhao et al, 2025).

Family care is typically defined as emotional support, quality of communication, and functional adaptability among family members (Smilkstein, 1978). According to ecological theory, families shape an individual’s developmental path through direct interactions (such as parent-child communication) and indirect factors (such as economic resources) (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). At present, the widespread adoption of online education has blurred the boundary between family and other social settings, making it more likely for adolescent self-concept development to be influenced by family environment factors (Branje et al, 2021). A study focusing on adolescents found that a cohesive, organized, and proactive family environment supports the development of self-concepts (Xiang et al, 2022). Among different parenting styles, nuclear families and authoritative parenting help reduce negative emotions in adolescents and enhance their self-concept. Conversely, closed and authoritarian parenting styles can hinder social cognitive development, indirectly impacting their self-concept (Jabeen et al, 2024). Additionally, research suggests that parents with high levels of self-concept clarity may have children with clearer self-concepts (Crocetti et al, 2016), highlighting the important role family members play in shaping their children’s self-views. Strong family support is more likely to create a stable and supportive environment that fosters growth, benefitting adolescents in forming an explicit self-concept (Xiang et al, 2022). However, most research focuses on children and early teenagers, with limited attention given to college students. College students face challenges related to role changes, independent decision-making, and interpersonal restructuring (Yang, 2024). The way family support is provided may shift from direct intervention to emotional companionship (Arnett, 2000). As college students enter their early adulthood, the role of parents gradually changes. Although parents still provide financial support, they increasingly become the source of emotional support (Bartoszuk et al, 2019). The latest research reveals that the physical distance between college students and their families has increased, with family care now relying more on emotional support rather than direct intervention (Zhou et al, 2024). This shift in family care dynamics requires further exploration to understand its impact on development.

Emotion is a response to the cognitive evaluation of an event’s meaning during a person’s interaction with their environment (Lazarus, 1991), serving as a key element of information processing (Schwarz and Clore, 1983). It influences how individuals cognitively assess family interactions (Clore and Gasper, 2000). Empirical research shows that emotions can predict changes in the content and structure of self-concept (Showers et al, 1998), and negative emotions have a direct negative relationship with self-concept (Zhang et al, 2022). Research indicates that positive emotions expand cognitive resources and improve efficacy, while negative emotions can limit reflection through cognitive narrowing (Nolen-Hoeksema et al, 2008). A study involving 1210 teenagers found that individuals with social anxiety disorder are more sensitive to negative information related to themselves, which can lead to self-doubt and lower their self-concept (Xiang et al, 2023). Insights into the link between emotions and self-concept suggest that self-concept significantly impacts people’s emotions (Lohbeck et al, 2018) and their close relationships (Dailey et al, 2022; Wareham and Wagers, 2020). Individuals strengthen the integration and consistency of their self-concept through cognitive reappraisal, increase positive emotional experiences, and reduce negative emotions (Colombo et al, 2021). Non-adaptive strategies, such as suppression or rumination, can fragment the self-concept and cause self-cognition dissonance (Bahl and Ouimet, 2022). Based on emotion regulation strategies (Masters, 1991), this study proposes reasonable hypotheses: Emotions (positive/negative) serve as mediators between Family Care and Self-concept.

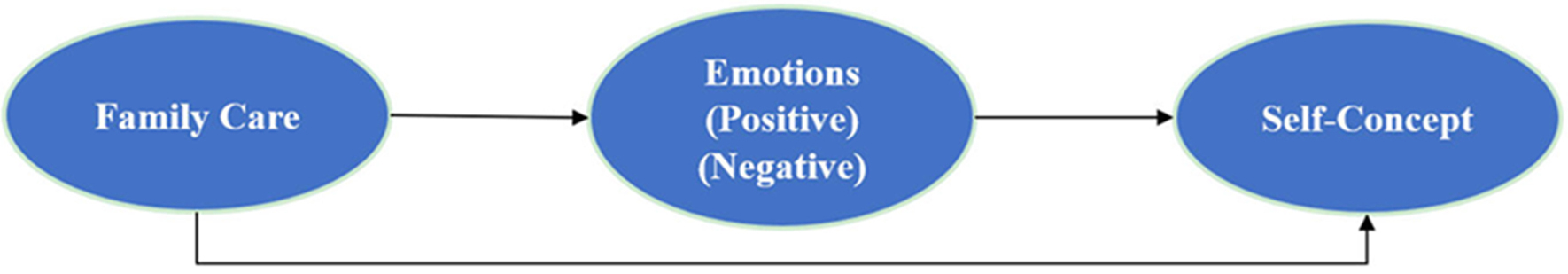

Previous studies primarily examined the direct effects of family factors on adolescents’ self-concept (Crocetti et al, 2016; Chen et al, 2022; Xiang et al, 2022). Some research also indicates that family care enhances emotional adaptability through situational choices, such as creating a low-conflict environment, and cognitive reappraisal, which involves positively reinterpreting setbacks, thereby helping to build a positive self-concept (Gross, 2015). In contrast, less attention has been given to the mechanisms that connect these factors. Additionally, studying how family care influences self-concept and the mediating role of emotions within the context of popular collective culture in East Asia can offer valuable theoretical insights and practical advice for mental health and development. Based on a review of relevant literature, we propose a hypothetical model showing how emotions mediate the relationship between family care and self-concept (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A mediation model based on hypotheses: emotions (positive/negative) as a mediating role between family care and self-concept.

At the end of the semester, just before summer vacation in early July, we surveyed college students from 30 classes across three universities in Jiangsu Province using cluster random sampling. After counselors explained the research purpose, students logged into the online survey tool “Wenjuanxing” (https://www.wjx.cn/) by scanning a quick response (QR) code and signed the electronic informed consent form. The questionnaire gathered social demographic information, including gender, grade, whether they were an only child, and place of residence, along with measurement data such as self-concept, family care, and positive and negative emotions. To encourage participation, students received a random red envelope reward after completing the survey.

Based on the ratio of items to sample size required for empirical research (Costello and Osborne, 2005), the sample size needed for this study was at least 10 to 20 times the number of scale items (Fang, 2007). This study had 40 measurement items, so the estimated sample size should have been between 400 and 800. Additionally, a 20% invalid response rate was taken into account. Ultimately, 1080 students participated in the survey, and 1058 valid questionnaires were collected, resulting in a response rate of 97.96%.

The exclusion criteria for the sample data are as follows: (1) Incorrect responses to the preset lie detector questions; (2) Missing answers to the questionnaire items; (3) A consistent response pattern; (4) Answering randomly and incoherently (for example, if the age was clearly outside the normal range).

We used the self-concept scale developed by Wallace (1990), which has been

validated by Chinese scholars and is considered reliable and valid (Yang, 2002). This scale is a single-dimensional scale without sub-dimensions, which

measures an individual’s overall self-concept by pairing 15 antonyms. It employs

a 7-point scale, with each item scored from 1 to 7, and six items are

reverse-scored. The score range is from 15 to 105, and the higher the score, the

better the individual’s self-awareness of various aspects of themselves. The

Cronbach’s

The Family APGAR Index was developed by Smilkstein (1978) and is based on

attributes of family functioning. Zhen (1996) has shown that it has good

reliability and validity when used with Chinese populations. It mainly assesses

how satisfied family members are with their family’s functioning. The

questionnaire contains five items: adaptability, cooperation, continuity,

emotional connection, and intimacy. Questions focus on these five areas to

evaluate family functioning, with responses scored as follows: 0 for “rarely”,

1 for “sometimes”, and 2 for “often”. The scores from these five questions

are summed; a higher total indicates better family functioning and more family

care. A total score of 7–10 signifies good family functioning, 4–6 indicates

moderate dysfunction, and 0–3 reflects severe dysfunction. The Cronbach’s

We used the PANAS (Watson et al, 1988), which has been validated by Chinese

researchers and demonstrates good reliability and validity (Huang et al, 2003). The scale contains 20 adjectives and assesses two emotional dimensions:

positive and negative emotions. It is analyzed statistically with two factors:

positive emotion scores (items 1, 3, 5, 9, 10, 12, 14, 16, 17, 19) and negative

emotion scores (items 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11, 13, 15, 18, 20). Higher scores in each

dimension indicate a higher level of that emotion. A high positive emotion score

suggests that an individual has abundant energy, can focus fully, and feels

emotionally happy, while a low score indicates a lack of emotional engagement. A

high negative emotion score reflects experiences of confusion and pain, whereas a

low score indicates calmness. In this study, the Cronbach’s

The Common Method Bias (CMB) was assessed using Harman’s single-factor test

(Zhou and Long, 2004), which checks if one factor explains most of the data variance.

Descriptive statistics were calculated and presented as mean (

Mediation effects were analyzed using Hayes’ PROCESS macro v4.1 and its Model 4 (Hayes and Rockwood, 2020), which employed bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to estimate 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Positive and negative emotions served as mediating variables, with self-concept as the outcome. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA).

The Harman univariate method was used to evaluate CMB. The exploratory factor analysis identified six factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, with the first factor explaining 28.988% of the variance, which is below the recommended threshold of 40% (Zhou and Long, 2004). This shows that the questionnaire survey results in this study are not significantly affected by CMB.

According to the analysis results in Table 1, the numerical features of the

surveyed college students’ demographic variables are presented, showing their

distribution. The mean reflects central tendency, while the SD indicates

variability. Table 1 also reveals significant differences between males and

females in positive and negative emotions, as well as in self-concept. Males have

higher levels of both positive and negative emotions and self-concept compared to

females (p

| Variables | N (%) | Self-concept | Family care | Positive emotion | Negative emotion | |||||

| ( |

t (p) | ( |

t (p) | ( |

t (p) | ( |

t (p) | |||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 306 (28.9) | 5.02 |

–2.174 (0.030) | 7.32 |

1.938 (0.053) | 3.56 |

3.735 ( |

2.52 |

3.101 (0.002) | |

| Female | 752 (71.1) | 5.16 |

7.17 |

3.39 |

2.35 | |||||

| Residence | ||||||||||

| Urban | 631 (59.6) | 5.14 |

1.093 (0.275) | 7.82 |

27.443 ( |

3.46 |

1.536 (0.125) | 2.37 |

–1.427 (0.154) | |

| Rural | 427 (40.4) | 5.08 |

6.33 |

3.41 |

2.44 | |||||

| Only child statue | ||||||||||

| Yes | 535 (50.6) | 5.15 |

1.342 (0.180) | 7.81 |

20.302 ( |

3.48 |

2.055 (0.040) | 2.37 |

–1.432 (0.153) | |

| No | 523 (49.4) | 5.08 |

6.61 |

3.40 |

2.43 | |||||

The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to examine the relationships between variables. As shown in the correlation analysis results in Table 2, all variables exhibited significant correlations with a p-value less than 0.01.

| Self-concept | Positive emotion | Negative emotion | Family care | |

| Self-concept | 1 | |||

| Positive emotion | 0.542** | 1 | ||

| Negative emotion | –0.454** | –0.159** | 1 | |

| Family care | 0.086** | 0.078* | –0.065* | 1 |

*, p

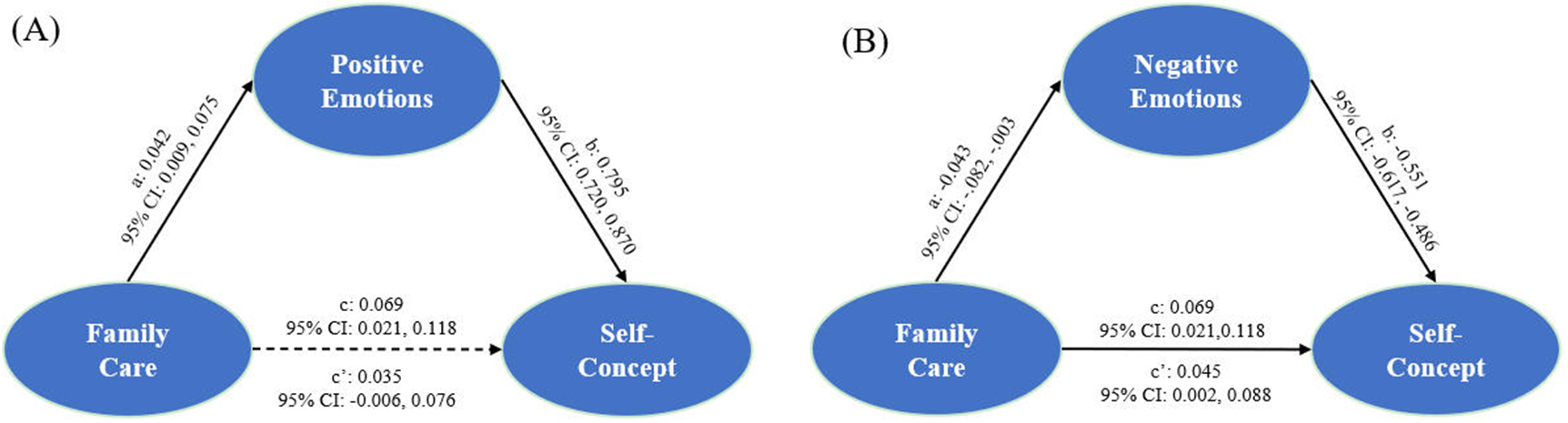

In the model with positive emotion as the mediator, family care had a significant positive effect on positive emotion (a: 0.042, 95% CI: 0.009 to 0.075), and positive emotion significantly influenced self-concept (b: 0.795, 95% CI: 0.720 to 0.870). After including positive emotion as a mediator, the effect of family care on self-concept became non-significant (c’: 0.035, 95% CI: –0.006 to 0.076), indicating that positive emotion fully mediated the relationship between family care and self-concept (indirect effect = 0.034, 95% CI: 0.078 to 0.589). Refer to Table 3 and Fig. 2A.

| Self-concept | Positive emotion (M1) | Self-concept | ||||||||||

| SE | 95% CI | SE | 95% CI | SE | 95% CI | |||||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||

| (Constant) | 4.620 | 0.180 | 4.268 | 4.973 | 3.136 | 0.122 | 2.897 | 3.375 | 2.129 | 0.193 | 1.750 | 2.508 |

| Family Care | 0.069 | 0.025 | 0.021 | 0.118 | 0.042 | 0.017 | 0.009 | 0.075 | 0.035 | 0.021 | –0.006 | 0.076 |

| Positive emotion | 0.795 | 0.038 | 0.720 | 0.870 | ||||||||

SE, standard error; LL, lower confidence limit; UL, upper confidence limit.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The mediating role of individual emotions in the relationship between family care and self-concept. (A) It shows the mediating role of positive emotions among college students in the relationship between family care and self-concept. (B) It indicates the mediating role of college students’ negative emotions in the relationship between family care and self-concept. a represents the effect of the independent variable (Family Care) on the mediating variable (Positive/Negative Emotion. ). b represents the effect of the mediating variable (Positive/Negative Emotion) on the dependent variable (Self-Concept). c’ represents the effect of the independent variable (Family Care) on the dependent variable (Self-Concept) after considering the mediating variable (Positive/Negative Emotion). c represents the total effect, which is c = ab + c’.

In the model where negative emotions act as the mediating variable, family care has a significant negative effect on negative emotions (a: –0.043, 95% CI: –0.082 to –0.003), and negative emotions have a significant negative impact on self-concept (b: –0.551, 95% CI: –0.617 to –0.486). This indicates that family care significantly influences self-concept (c’: 0.045, 95% CI: 0.002 to 0.088). At this point, negative emotions partially mediate the relationship between family care and self-concept (indirect effect = 0.024, 95% CI: 0.001 to 0.047). See Table 4 and Fig. 2B.

| Self-concept | Negative emotions (M2) | Self-concept | ||||||||||

| SE | 95% CI | SE | 95% CI | SE | 95% CI | |||||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | Se | LL | |||||||

| (Constant) | 4.620 | 0.180 | 4.268 | 4.973 | 2.710 | 0.147 | 2.422 | 2.998 | 6.115 | 0.185 | 5.753 | 6.477 |

| Family Care | 0.069 | 0.025 | 0.021 | 0.118 | –0.043 | 0.020 | –0.082 | –0.003 | 0.045 | 0.022 | 0.002 | 0.088 |

| Negative emotion | –0.551 | 0.034 | –0.617 | –0.486 | ||||||||

This study explored how positive and negative emotions mediate the link between family care and college students’ self-concept. Supporting prior research (Hong et al, 2022; Milenkova and Nakova, 2023; Sánchez-Urrea et al, 2024), our data revealed that positive emotion fully mediates this connection, while negative emotion only partially mediates it.

The self-concept score of college students exhibits a strong positive correlation with positive emotions and a strong negative correlation with negative emotions. Family support is positively linked to the self-concept score, suggesting that increased family support is associated with a more positive self-concept. Furthermore, family support is significantly positively associated with positive emotions and negatively associated with negative emotions, indicating that greater family support correlates with higher positive emotion and lower negative emotion.

Family care, an essential part of socialization, plays a vital role in shaping self-concept by providing support and nurturing its members. This study examines the strong positive relationship between family care and self-concept among college students, which aligns with Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory. This theory suggests that families influence individuals’ psychological growth through direct interactions (such as emotional support) and indirect resources (like economic security). Specifically, family care helps establish stable emotional bonds, as indicated by the ‘adaptability’ and ‘closeness’ dimensions of the APGAR scale, providing college students with a strong foundation for a positive self-view (Shavelson et al, 1976). Furthermore, recent research (Eccles and Wigfield, 2020) indicates that such care promotes the development of positive perceptions of abilities and worth. For instance, effective communication within families significantly enhances a person’s social role identity. Additionally, a healthy family environment, characterized by ‘cooperativeness’ and ‘continuity’, reduces role conflicts and clarifies self-concept (Cummings and Davies, 2010). A study on the self-concept of patients with brain trauma indicates that adaptability, as one of the five dimensions of the APGAR scale, is positively correlated with self-concept (Li-hon, 2014). Research on the correlation between collaboration degree and self-concept indicates that when family members discuss issues together and participate in decision-making, there is a positive correlation. Such a collaborative environment can enhance an individual’s autonomy and thereby improve their self-concept (Elvira et al, 2023). Family functions shape attachment patterns, thereby influencing the self-concept. Affinity reflects an individual’s emotional expression and acceptance. Research has found that attachment avoidance is negatively correlated with the self-concept, while secure attachment can enhance the stability of self-awareness (Kural and Kovács, 2022).

Family care, an essential psychological nurturing resource, not only directly shapes an individual’s self-concept but also profoundly influences their psychological development by regulating emotional states. Studies have shown that when teenagers receive emotional support from their parents, their positive emotions increase; conversely, when they experience emotional neglect, their negative emotions rise (Griffith and Hankin, 2025). Wang et al. (2022) found that adverse family environments—such as high conflict and low cohesion—along with inappropriate parenting styles and low-quality parent-child relationships, contribute to an increase in teenagers’ negative emotions, and in severe cases, may lead to depression. This phenomenon can be explained by the emotion regulation theory proposed by Gross (2015). This indicates that family care can not only foster a positive family atmosphere and reduce conflicts but also enhance individuals’ positive emotions. It can also guide teenagers to view and handle adverse events, such as setbacks, from a more positive perspective. Additionally, the ‘adaptive’ characteristic of family function—the ability to respond flexibly to external environmental changes—can effectively decrease negative emotional responses caused by uncertainty (Smilkstein, 1978), thereby providing strong support for individual mental health.

The primary finding of this study is the distinct mediating effects of emotions: positive emotions fully mediate the relationship between family care and self-concept, whereas negative emotions only partially mediate it. The following section explores the reasons behind this difference in terms of functional pathways and theoretical mechanisms. Emotions, as the primary response of an individual to the environment (Lazarus, 1991), have been confirmed in this study as an important mediator in shaping self-concept. The results indicate that positive emotions are positively associated with self-concept, while negative emotions are negatively associated with it. This supports the Broaden-and-Build Theory (Fredrickson, 2001), which suggests that positive emotions can expand cognitive resources and boost an individual’s confidence in abilities, such as ‘concentration’ and ‘happiness’, leading to positive self-evaluation. For example, students experiencing high levels of positive emotions are more likely to see academic challenges as opportunities for growth, which enhances their academic self-concept (Murn and Steele, 2020). Conversely, negative emotions limit reflection through the narrowing of the cognitive effect (Nolen-Hoeksema et al, 2008). Additionally, the negative link between negative emotions and self-concept aligns with the Mood-Congruence Hypothesis (Schwarz and Clore, 1983), which states that emotional states activate self-cognitive content consistent with those emotions. This mechanism explains why individuals with stronger negative emotions tend to develop a negative self-concept.

The discovery of the fully mediating role of positive emotions shows that the effect of family care on self-concept is entirely mediated through positive emotions. This finding aligns with the resource gain model (Hobfoll, 2001), which suggests that family support enhances self-concept by promoting positive emotions and facilitating the development of psychological resources, such as optimism and resilience (Nurhidayati et al, 2023). Specifically, the sense of security provided by family care makes people more likely to experience positive emotions, such as happiness and interest, which then boost self-evaluation through cognitive growth. Positive emotions broaden attention, encouraging individuals to recognize their strengths more widely (Fredrickson, 2001). Improving social connections: People with high positive emotions are more likely to form supportive relationships, which offer external feedback that helps strengthen their self-concept (Wareham and Wagers, 2020).

Research suggests that, through its partial mediating role in negative emotions, family care indirectly strengthens self-concept by reducing negative emotions and directly has a positive impact on self-concept. This phenomenon can be understood from multiple perspectives. First, the effect of family care is complex and likely involves several unknown intermediary variables, such as social support (Camara et al, 2017; Triana et al, 2019), which influence self-concept through various regulatory mechanisms. These variables are vital in the intricate interaction between family care and self-concept. College students who faced adverse events early in adolescence are more prone to develop negative self-evaluations and social withdrawal (Pan et al, 2024). A high-functioning family environment helps individuals build a positive self-view and improves their ability to manage interpersonal conflicts by offering emotional support and recognition of their individuality (Qian et al, 2022). Additionally, triggering negative emotions may activate a person’s defense mechanisms (Frederickson et al, 2018). Such adaptive responses, including problem-focused coping strategies (Ewing and Hamza, 2024), assist individuals in actively adjusting their self-evaluation, thereby somewhat reducing the harmful effects of these emotions. For instance, students who feel they lack adequate family care might seek support from peers to fill emotional gaps (Sahi et al, 2023). This compensatory behavior can help lessen the negative effects of emotions. Moreover, the partial mediating role of negative emotions highlights its inherent ‘double-edged sword’ nature: moderate negative emotions, like mild anxiety, can encourage self-reflection and foster growth (Tietjen, 2020); however, when negative emotions become overwhelming, they can lead to self-criticism (Jin et al, 2022), adversely affecting mental health. Therefore, family care’s role is not only to diminish negative emotions but, more importantly, to assist individuals in developing and improving emotional regulation strategies to maintain emotional balance and promote positive development of their self-concept (Lei et al, 2022; Zhou et al, 2023).

The family plays a vital role in the development of teenagers’ self-awareness (Milenkova and Nakova, 2023). Good family care can boost positive emotions in teenagers, lessen negative emotions, and thus improve their self-concept (Griffith and Hankin, 2025). In daily life, consistent with this research perspective, we recommend that parents engage in more emotional communication with their teenagers and build emotional bonds (Ratliff et al, 2023). For fostering positive emotions, encouragement and prompt positive responses should be provided. When negative emotions occur, it is important to guide individuals to view setbacks correctly and to analyze and handle negative events from a positive angle (Eisenberg et al, 2008). For teenagers, Li et al. (2022a) discovered that gratitude plays a crucial bridging role between parent-child relationships and the development of teenagers. Therefore, we suggest that schools implement gratitude education for teenagers, encouraging and guiding them to communicate more with their families and to recall more instances of gratitude shared with their families. Through parental and student interventions, promote effective two-way communication, establish strong emotional bonds, and enhance teenagers’ self-concept.

Although this study shows how family care influences self-concept through emotional mediation, it still has some limitations. First, because of its cross-sectional design, it cannot establish causality. Emotions and self-concept may influence each other in both directions; future research should use longitudinal studies or experimental methods to clarify the causal relationship. Second, a limitation is that the sample only includes college students across three universities in Jiangsu Province, which may not represent other regions. Increasing the sample size is important to see if these findings apply more broadly. Future research could explore cross-cultural differences, such as how family care works in collectivist versus individualist cultures, by analyzing how individualism impacts emotional mediation in Western families. This study focused solely on the family as an external factor. Future studies should include more social and school factors, such as teachers and peers.

This study shows that family care significantly influences college students’ self-concept, impacting both positive and negative emotions. Positive emotions fully mediate this relationship, whereas negative emotions only partially do. The results highlight the importance of family support and emotional regulation in shaping self-concept. Future studies should use longitudinal designs and include diverse groups to validate these findings further. Interventions focused on family support and emotional well-being are advised to improve college students’ mental health.

The data used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

HX and XL conceived the study, supervised the process, and performed the analyses. TY developed and executed the literature search strategy, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscripts. LP and CZ compiled the data and conducted the data analysis. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Research was carried out following the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and received approval (Approval Number: XMUs-22/0406) from the Ethics Committee of Xuzhou Medical University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The authors express gratitude to all participants in this study.

This study belongs to the Special Subject Key Project ‘Jiangsu Higher Education’ of the Jiangsu Higher Education Association (2022JSGJKT008).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.