1 Department of Education, Valencian International University, Faculty of Education, 46002 Valencia, Spain

2 Department of Basic Psychology, University of Valencia, Faculty of Psychology, 46010 Valencia, Spain

Abstract

In adolescence, personality traits and emotion regulation strategies play a key role in psychosocial development. However, literature shows inconsistencies in how these variables interact and how gender may influence this relationship.

The study involved 703 Spanish adolescents (49.9% boys) aged 15 to 18. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) assessed cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, while the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) measured the Big Five personality traits. Correlational analyses and path models were conducted, separated by gender.

Extraversion and emotional stability were positively associated with cognitive reappraisal and negatively with expressive suppression. These associations were stronger in girls, where extraversion also predicted cognitive reappraisal. Traits like agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness showed no consistent significant associations with emotion regulation strategies.

Extraversion and emotional stability stand out as key predictors of emotion regulation during adolescence. These findings support the promotion of these traits in educational interventions to foster adaptive emotional strategies.

Keywords

- big five personality traits

- emotion regulation

- adolescence

- cognitive reappraisal

- expressive suppression

Research on personality has tended to focus more on adult age and less on earlier ages (Chopik and Kitayama, 2018; Schmitt et al, 2017). However, in recent years, research focused on adolescence and emerging adulthood has emerged (Borghuis et al, 2017). Personality traits refer to specific psychological processes, which, together with adaptations derived from environmental influences, determine relatively permanent patterns of thought, feelings and behaviour (DeYoung, 2015; Hughes et al, 2020; McCrae and Costa Jr, 2003; McCrae and Sutin, 2018). The permanent nature of traits is weaker in adolescence, a stage during which people become more unstable (Canals et al, 2005). Accordingly, research has shown that adolescence is linked to changes in patterns of behaviour and temperament that are influenced by environment (Kawamoto and Endo, 2019; McCrae and Sutin, 2018; Van den Akker et al, 2021).

The five-factor model of personality (FFM) reflects a two-dimensional approach based on polar opposites: extraversion-introversion, agreeableness-antagonism, neuroticism-emotional stability, conscientiousness-negligence and openness-closedness (Nichols and Pace, 2020). Research has shown strong relationships of covariance between them (Van der Linden et al, 2016), implying that they can be structured around a higher-order personality factor and a general factor of personality (van der Linden et al, 2017).

Various studies have shown that age, sex and social and cultural context are related to individuals’ development of personality traits. In relation to age, a longitudinal study from adolescence to emerging adulthood verified that variations are greater at the beginning of adolescence and that, as an individual matures, personality traits become more stable (Borghuis et al, 2017). The evolution of an individual’s personality follows a U-shaped curve, with emphasis on agreeableness, awareness, openness and emotional stability, during the maturational change from early adolescence to late adolescence. These changes are linked to self-regulation mechanisms such as positive cognitive reappraisal of threatening events, and they encourage trait stability at a later stage (Denissen et al, 2013; Hallion and Ruscio, 2011).

Regarding sex, the differences between men and women are more pronounced in advanced societies with greater economic development (Schmitt et al, 2017). However, the literature is inconclusive on sex differences, owing to the large number of factors potentially involved. Such factors range from physiological aspects to cultural and social aspects such as gender roles (Bunnett, 2020).

In relation to culture, a study with U.S. and Japanese respondents confirmed significant differences in extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness and agreeableness but not in openness (Chopik and Kitayama, 2018). The same authors concluded that these differences are linked to culture and the transitions of values and social roles (Wagner et al, 2016). They even observed that patterns of change tend to be more consistent in U.S. Americans and more random in the Japanese (Chopik and Kitayama, 2018).

Another key concept is emotion regulation. It alludes to the processes that allow people to manage their emotions to respond in an adaptive manner to the demands of the environment and to manage emotions in social interactions (Gross and John, 2003; Tamir et al, 2020; Zimmermann and Iwanski, 2014). It entails the management of positive and negative emotions by up- or down-regulating them (McRae and Gross, 2020). Scholars have found that difficulties in emotion regulation are related to emotional dependence (Momeñe et al, 2017). Therefore, there is growing interest in analysing the ways in which people regulate and manage their emotions (Cameron and Overall, 2018; Cludius et al, 2020; English et al, 2012).

The model of emotion regulation processes (Gross, 2015) comprises two dimensions related to the use of emotion regulation strategies. The expressive dimension (cognitive reappraisal) alludes to strategies that are activated before the emotional experience occurs. This dimension is cognitive and refers to antecedent-focused strategies. The repressive dimension (expressive suppression) alludes to strategies that are implemented once the emotional process has been activated. This dimension refers to inhibitory, response-focused strategies (Gross, 2015; McRae and Gross, 2020). This model explains the emotional, social, cognitive and physiological costs associated with the use of expressive suppression strategies, as well as the benefits of cognitive reappraisal strategies (Gross and Cassidy, 2019).

Studies have shown that these two types of strategies follow different emotion management processes and occur independently of approach or avoidance social goals in social relationships (Cameron and Overall, 2018). The use of these strategies varies throughout the life cycle. Response-focused strategies are more common in childhood, whereas antecedent-focused (expressive) strategies usually become more common with maturity. As people get older, they learn to manage their emotions effectively (Haga et al, 2009; Stifter and Augustine, 2019). Successful emotion regulation can be considered a basic part of the transition from childhood to adulthood (Perry et al, 2020).

Scholars have shown that the use of cognitive reappraisal provides intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits and has more adaptive outcomes. For example, it enables better interactions with others and reduces the symptoms of primary and secondary psychopathology such as manipulative behaviour, pathological lying, antisocial behaviour, an unstable lifestyle, impulsiveness and criminality (Cludius et al, 2020; Walker et al, 2022). Conversely, expressive suppression incurs high intrapersonal costs and is linked to a lower level of well-being and greater difficulties in establishing social relationships (Cameron and Overall, 2018; English and Eldesouky, 2020), as well as psychopathological behaviour (Walker et al, 2022). In general, expressive suppression tends to be maladaptive in the long term, although it may be adaptive in certain stressful or traumatic situations (Harrington et al, 2020; Westphal et al, 2010).

Regarding differences by sex, the literature provides inconclusive findings, although it seems that men tend to have greater emotion self-regulation (Falcó et al, 2020). In terms of cognitive reappraisal, some studies have not found significant differences (Balzarotti et al, 2010; Gross and John, 2003; Haga et al, 2009), whereas others have found small significant differences between men and women, with lower levels in men (Gullone et al, 2010; Kokkinos et al, 2019). In terms of expressive suppression, the literature reports higher levels in boys (Gross and John, 2003; Gullone et al, 2010; Haga et al, 2009). However, it seems that adolescent boys tend to employ not only more adaptive emotional strategies but also more maladaptive ones (Sabatier et al, 2017). Therefore, the differentiating role of sex in emotion regulation variables in adolescents is unclear, and further analysis is of interest (Kokkinos et al, 2019).

Personality traits may be involved in the way that people regulate their own and others’ emotions in order to achieve their goals (Hughes et al, 2020). Scholars have found that personality traits can predict emotion regulation in emerging adults and adults (Eldesouky and English, 2019), although the findings are inconclusive. For example, the positive predictive variables of cognitive reappraisal have been observed to be extraversion and conscientiousness among Iranians (7% of the variance) but extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness among Indonesians (25.8% of the variance). For expressive suppression strategies, the positive predictive variables were observed to be extraversion and conscientiousness in Iranians (8% of variance). Among Indonesians, the negative predictive variables were agreeableness and extraversion, while neuroticism acted as a positive predictor explaining 24.9% of variance (Purnamaningsih, 2017; Sadr, 2016).

In a recent meta-analysis, Barańczuk (2019) found that high scores in extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness, together with low scores in neuroticism, were positively associated with cognitive reappraisal and negatively associated with suppressive strategies.

Overall, research on the relationships between personality traits and emotion regulation strategies has provided inconsistent findings, revealing country- and culture-based differences. Cognitive reappraisal seems to be positively related to extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience and negatively related to neuroticism, as supported by findings in studies with U.S., European and Australian respondents (Balzarotti et al, 2010; Barańczuk, 2019; Gračanin et al, 2020; Gresham and Gullone, 2012; Gross and John, 2003) and with Indonesian and Chinese respondents (Purnamaningsih, 2017; Shi et al, 2018). Some studies have also shown that cognitive reappraisal is related to extraversion and emotional stability-neuroticism. These studies considered participants from Australia and the United States (Haga et al, 2009), China (Wang et al, 2009), Poland (Kobylińska et al, 2020), Iran (Sadr, 2016) and Spain (Cabello et al, 2013). However, other studies have failed to find significant relationships between cognitive reappraisal and neuroticism or openness to experience among Iranians (Sadr, 2016) and between cognitive reappraisal and conscientiousness among Spaniards (Cabello et al, 2013) and Germans (Schindler and Querengässer, 2019).

Regarding relationships with personality traits, expressive suppression is associated positively with neuroticism and negatively with extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness (Barańczuk, 2019). These findings are similar to those observed with respondents from China (Shi et al, 2018; Wang et al, 2009) and Poland (Kobylińska et al, 2020). However, some studies have failed to show significant relationships between expressive suppression and some personality traits such as agreeableness among Iranians (Sadr, 2016), openness to experience among Australians (Gresham and Gullone, 2012), conscientiousness among Spaniards (Cabello et al, 2013) and agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and openness among Croats, Germans (Gračanin et al, 2020; Schindler and Querengässer, 2019) and Indonesians (Purnamaningsih, 2017).

The most divergent relationship is between expressive suppression and neuroticism. Several key aspects are worth noting. First, studies have confirmed negative relationships between these two variables (Cabello et al, 2013; Ioannidis and Siegling, 2015). Second, positive relationships between neuroticism and expressive suppression have been observed (Kobylińska et al, 2020; Gresham and Gullone, 2012; Sadr, 2016; Shi et al, 2018). Third, in a meta-analysis by Barańczuk (2019), the relationship was not found to be significant when expressive suppression was divided into two dimensions (suppression of thoughts and emotions and suppression of emotional expression). Gross and John (2003) and Haga et al (2009) have also reported the absence of a link between neuroticism and expressive suppression in respondents from the United States, Australia and Norway. A possible explanation for these somewhat inconsistent findings may relate to cultural phenomena. The instrumental value of emotions and the way they are expressed may be determined by whether cultures are more collectivist, such as Oriental cultures, or more individualistic, such as European or North American cultures (Ma et al, 2018; Matsumoto, 2006).

Finally, there seems to be a consensus regarding the negative relationships between expressive suppression and extraversion, regardless of the country of origin of the sample (Balzarotti et al, 2010; Barańczuk, 2019; Cabello et al, 2013; Gračanin et al, 2020; Ioannidis and Siegling, 2015; Kobylińska et al, 2020; Purnamaningsih, 2017; Sadr, 2016; Schindler and Querengässer, 2019; Shi et al, 2018; Wang et al, 2009).

Considering these findings, this study examines the links between personality traits and the use of emotion regulation strategies, which, so far, have not been studied in adolescent populations. As mentioned earlier, in this development stage, personality goes through a process of changes and adjustments, linked to development. Based on statistical procedures of path analysis, this study provides descriptive and explanatory insight into the possible relationships between these variables (Ato et al, 2013).

Specifically, this study has two aims: (i) to analyse the relationships between personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability and openness to experience) and emotion regulation strategies (expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal) and (ii) to analyse the role of personality traits on emotion regulation considering the adolescents’ sex. This study uses emotional stability instead of neuroticism, based on the approach of polar opposites in personality traits (Nichols and Pace, 2020). The theoretical model is presented graphically in Appendix Fig. 2. Supported by this literature review, the following two hypotheses are proposed: (1) The personality traits of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability and openness to experience are negatively related to expressive suppression and positively related to cognitive reappraisal, and (2) personality traits, especially extraversion and emotional stability, predict cognitive reappraisal positively and expressive suppression negatively.

Participants were 703 adolescents, of whom 351 were boys (49.9%) and 352 were girls (50.1%). They were aged 15 to 18 years (M = 15.86, SD = 0.30). The distribution by age was as follows: 15 years (35.7%), 16 years (46.2%), 17 years (13.9%) and 18 years (4.1%). They were enrolled in the fourth year of compulsory secondary education and post-16 education in eight schools in the province of Valencia (Spain). Of these participants, 49.5% studied in public (state) schools, and 50.5% studied in semi-private schools.

Regarding family structure, 78.7% of participants belonged to two-parent families, and 17.8% to single-parent families. Regarding the family’s country of origin, 92.7% were Spanish, 1.4% were from the rest of Europe, 5.1% were Latin American, 0.3% were from sub-Saharan Africa and 0.4% were from Southeast Asia.

The level of studies of the parents was as follows: incomplete primary studies (fathers 2%, mothers 0.6%), complete primary studies (fathers 28.2%, mothers 23.6%), post-16 studies (fathers 43.7%, mothers 41.7%) and university (fathers 25.3%, mothers 33.7%). There were no data on this item for 1.3% of parents.

(a) Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross and John, 2003), adapted to Spanish by Cabello et al (2013). The ERQ evaluates the use of two emotion regulation strategies: cognitive reappraisal (e.g., “When I want to feel more positive emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation”) and expressive suppression (e.g., “I keep my emotions to myself”). It consists of 10 items presented on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). A total score is obtained for each subscale by adding the direct responses. A higher score indicates greater use of the strategy. Cognitive reappraisal refers to the cognitive change that occurs before the emotion is triggered and modifies the emotional impact of the situation, while cognitive suppression occurs after the emotion is generated and involves an inhibition of emotional expression. Cronbach’s

(b) Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI; Gosling et al, 2003), adapted to Spanish by Romero et al (2012). The TIPI is a brief measurement instrument (10 items) that evaluates the big five personality traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experiences. Items are answered on a 1–7 scale (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = totally agree). Each personality trait is evaluated through two items, one represses the positive pole of the dimension and the other the negative pole (e.g., extraversion-introversion to the question “How do you see yourself” as “Extraverted, enthusiastic, cheerful” or “Reserved, quiet”). Each factor results from adding the direct and inverse scores of the corresponding items. The higher the score, the more the personality trait is reported. The TIPI is conceptualised following behaviour domain theory in terms of behaviour domains, estimating constructs through inference based on generalisations to the population (Myszkowski et al, 2019). Short personality questionnaires based on the five-factor model of personality (FFM) have been found to have acceptable psychometric properties. They tend to be validated in different countries and languages for reasons of economy of effort (Gignac and Szodorai, 2016; Nunes et al, 2018; Robles-Haydar et al, 2022; Romero et al, 2012). The questionnaire performed similarly to other longer personality questionnaires (Gosling et al, 2003; Myszkowski et al, 2019). Cronbach’s alpha for each factor was as follows: extraversion

This study was cross-sectional. Sample selection considered the list of secondary schools and the type of ownership (public or semi-private) of schools in the province of Valencia (Spain). The aim was to cover the school student population enrolled in both types of schools. The study received approval from the schools and families. The study followed the ethical guidelines stipulated in the Declaration of Helsinki for research of this type. The families and students gave their consent. Participation was voluntary, anonymous and confidential. Students could withdraw from the study at any time if they so wished. However, no student withdrew. The evaluation was performed in groups in the classroom. Two professional experts and one schoolteacher were present in the classroom during the evaluation to answer questions and avoid missing data. The sessions lasted approximately 45 minutes. There were no missing data.

Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA, 2016) and Mplus 8 (Muthén and Muthén, Los Ángeles, CA, USA, 2017) (Muthén and Muthén, 2017). First, analysis of differences of means was conducted using the t test for independent samples. The study variables were the Big Five personality traits and the emotion regulation strategies of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. The aim was to observe significant differences by participants’ sex and effect sizes. Second, correlation analysis was conducted, differentiating by sex. Finally, path analysis was performed to evaluate the fit of the proposed theoretical model for the dependent and independent variables. The independent variables were the Big Five personality traits. The dependent variables were cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. The goodness of fit was calculated using the following robust estimators: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) and comparative fit index (CFI). A good fit is indicated by SRMR values of less than 0.05, RMSEA values of less than 0.08 and CFI values of more than 0.90 (Bentler, 1990; Hooper et al, 2008).

The population had mean values (arithmetic means) that were slightly higher than the mean indices for the questionnaire items (Table 1). Openness and agreeableness had higher arithmetic means for both men and women.

| Mean | Standard deviation | Asymmetry | Curtosis | Min | Max | |||||

| M | W | M | W | M | W | M | W | |||

| Extraversion | 4.88 | 4.90 | 1.28 | 1.27 | –0.126 | 0.132 | –0.954 | –0.867 | 2.50 | 7.00 |

| Agreeableness | 4.98 | 5.04 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.011 | 0.066 | –0.850 | –0.919 | 3.50 | 6.50 |

| Conscientiousness | 4.81 | 4.98 | 1.08 | 1.14 | 0.113 | 0.017 | –0.867 | –0.920 | 3.00 | 7.00 |

| Emotional stability | 4.46 | 4.13 | 1.17 | 1.21 | –0.224 | 0.008 | –0.637 | –0.773 | 2.00 | 6.50 |

| Openness | 5.37 | 5.47 | 1.07 | 1.04 | –0.090 | –0.222 | –1.050 | –0.853 | 3.50 | 7.00 |

| Cognitive reappraisal | 4.60 | 4.20 | 0.98 | 0.94 | –0.130 | 0.026 | –0.438 | –0.548 | 2.50 | 6.33 |

| Expressive suppression | 3.87 | 3.58 | 1.28 | 1.23 | –0.047 | 0.063 | –0.990 | –0.927 | 1.50 | 6.00 |

Note: M, men; W, women; p

The results of the correlation analysis appear in Table 2. Adolescent boys’ cognitive reappraisal was significantly and positively associated with all Big Five personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability and openness). However, in adolescent girls, only the relationships with extraversion (r = 0.184; p

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 1. Extraversion | - | 0.049 | 0.144** | –0.141** | 0.320** | 0.110* | –0.268** |

| 2. Agreeableness | –0.038 | - | 0.109* | 0.410** | 0.045 | 0.136* | –0.051 |

| 3. Conscientiousness | 0.081 | 0.191** | - | 0.110* | 0.132* | 0.131* | –0.026 |

| 4. Emotional stability | –0.120* | 0.470** | 0.160** | - | 0.046 | 0.212** | 0.078 |

| 5. Openness | 0.361** | 0.030 | 0.035 | –0.005 | - | 0.148** | –0.080 |

| 6. Cognitive reappraisal | 0.184** | 0.050 | 0.068 | 0.231** | 0.157** | - | 0.048 |

| 7. Expressive suppression | –0.332** | –0.017 | –0.020 | 0.109* | –0.156** | 0.047 | - |

Notes: p

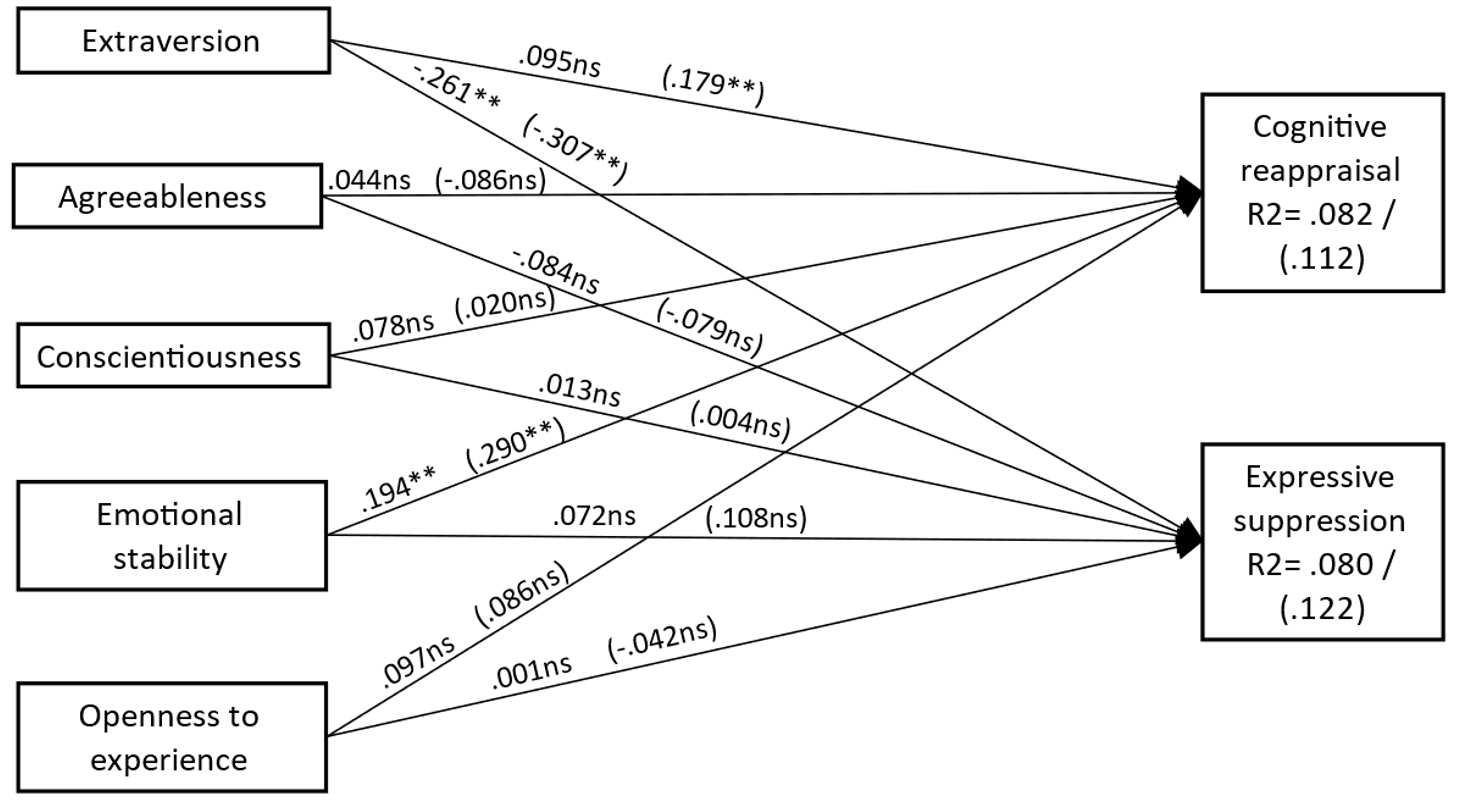

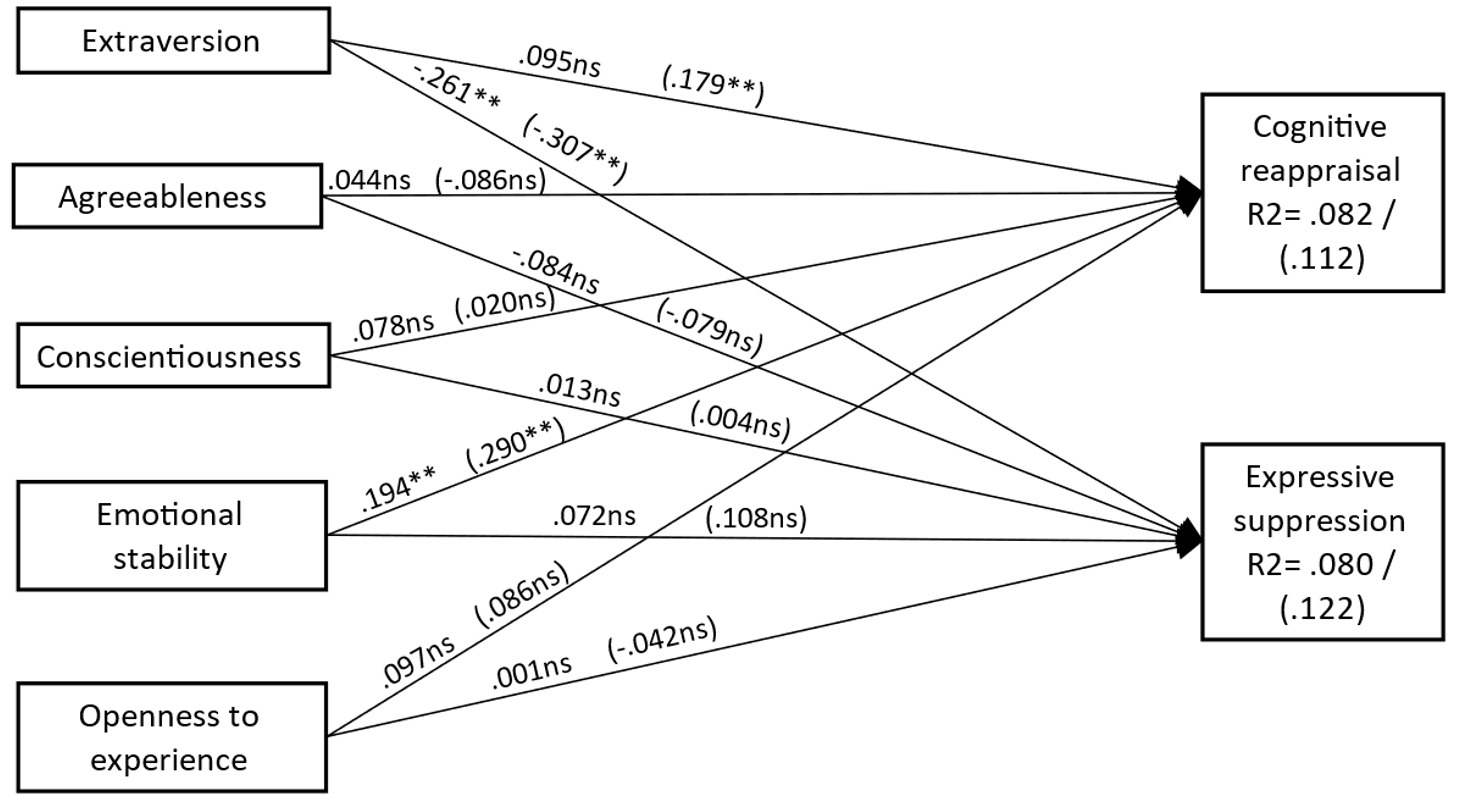

The path analysis model was used to study the effect of each of the Big Five personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability and openness) on cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. The path analysis model was applied for girls and boys to identify any differences in the direct effects of the personality variables on the dependent variables of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. This model was estimated using the direct scores for the items in the TIPI questionnaire because each dimension consisted of two items. All variables were quantitative, so a robust estimator for quantitative variables was chosen, namely maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR). Accordingly, this path analysis had five antecedent (explanatory) variables and two consequent (explained) variables. The resulting model had a satisfactory fit: (

Fig. 1 shows the results for the theoretical model. Significant and non-significant effects for boys and girls are indicated. The standardised effects in the model for the two subsamples are provided. The scores for girls appear in parentheses.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Model of personality and emotion regulation for girls and boys. Notes: Values in parentheses are those for adolescent girls; ns, non-significant. **p

The patterns of relationships were quite similar, with small variations between adolescent girls and boys. The paths from extraversion and emotional stability showed significant relationships with emotion regulation strategies. Extraversion was negatively associated with suppression (

The results revealed a negative effect of extraversion on expressive suppression (in boys and girls). They also showed a positive effect of emotional stability on cognitive reappraisal in boys and girls. Finally, in girls, the results indicated a positive effect of extraversion on cognitive reappraisal. Therefore, among adolescent girls, extraversion and emotional stability seemed to foster cognitive reappraisal. The personality traits of agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience did not have significant relationships with the two dimensions of emotion regulation.

The aim of this study was to analyse the relationships between the Big Five personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability and openness to experience) and the emotion regulation strategies of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Moreover, the study aimed to analyse the effects of these personality traits on emotion regulation, differentiating between the sex of the adolescents participating in the study.

In view of the results, several conclusions can be noted. First, an initial examination shows that cognitive reappraisal is more strongly and positively associated with emotional stability, openness to experience and extraversion in both boys and girls. It seems that adolescents who are more emotionally stable and open to new experiences will be better prepared to cope with situations by using more adaptive regulation strategies that encourage emotional expression and help them achieve their goals (Barańczuk, 2019). This situation is similar for both boys and girls. However, for the current sample of adolescents, the links with agreeableness and conscientiousness are less clear, with weak relationships observed only in boys. A similar situation has been observed with participants from Germany (Schindler and Querengässer, 2019) and China (Shi et al, 2018). Overall, the results of the current study are in line with those of previous research (Balzarotti et al, 2010; Gresham and Gullone, 2012; Gross and John, 2003; Haga et al, 2009; and Purnamaningsih, 2017).

Regarding the relationships between personality traits and expressive suppression, stronger negative links with extraversion are observed. Seemingly, extraverted adolescents are better prepared to curb emotional suppression strategies. These response-focused strategies tend to have more maladaptive social outcomes (Gross and Cassidy, 2019). More extraverted adolescents are better prepared to avoid inhibitory emotional strategies that aim to hide emotions, which can negatively affect personal well-being (Cameron and Overall, 2018; Cludius et al, 2020; English and Eldesouky, 2020).

Prior research has shown certain discrepancies in the relationships between expressive suppression and personality traits. These discrepancies can be summarised as follows: (i) Expressive suppression is negatively related to extraversion (Barańczuk, 2019). (ii) Significant relationships with agreeableness are not observed (Gračanin et al, 2020; Purnamaningsih, 2017; Sadr, 2016; Schindler and Querengässer, 2019). In both cases, the results for extraversion and agreeableness are consistent with those observed in the present study, although other studies have found negative relationships between agreeableness and expressive suppression (Barańczuk, 2019; Cabello et al, 2013; Kobylińska et al, 2020; Purnamaningsih, 2017; Shi et al, 2018). (iii) A similar situation is observed for conscientiousness. Some studies have failed to find significant relationships between these variables, as is the case in the present study (Cabello et al, 2013; Gračanin et al, 2020; Ioannidis and Siegling, 2015; Schindler and Querengässer, 2019). In contrast, other studies have found negative correlations (Barańczuk, 2019; Gresham and Gullone, 2012; Gross and John, 2003; Purnamaningsih, 2017; Shi et al, 2018). (iv) For emotional stability (the opposite of neuroticism), the findings of the present study differ to some degree from certain previous studies (Barańczuk, 2019; Gresham and Gullone, 2012; Sadr, 2016; Shi et al, 2018), which have found a positive relationship between neuroticism and expressive suppression. However, other scholars have reported findings along the lines of those observed in this study. For example, for an Italian sample, Balzarotti et al (2010) found negative relationships between neuroticism and reappraisal and between neuroticism and suppression. (v) Regarding the trait of openness, a negative relationship with expressive suppression is observed among the female sample, echoing the findings of Balzarotti et al (2010), Barańczuk (2019), Gross and John (2003), Sadr (2016) and Shi et al (2018). In contrast, in the male sample, no correlation is observed. This finding supports those of other studies (Gračanin et al, 2020; Gresham and Gullone, 2012; Ioannidis and Siegling, 2015; Purnamaningsih, 2017; Schindler and Querengässer, 2019).

These findings may seem contradictory. A possible explanation could lie in the cultural and instrumental features of the research (Eldesouky and English, 2019; Ma et al, 2018; Matsumoto, 2006). The divergent studies by Gresham and Gullone (2012), Sadr (2016) and Shi et al (2018) used samples from Australia, Iran and China, respectively. In contrast, the studies that provide consistent findings with those of the present study used samples from countries that are geographically and culturally closer such as Italy (Balzarotti et al, 2010), Spain (Cabello et al, 2013), Croatia (Gračanin et al, 2020), Norway (Haga et al, 2009) and Germany (Schindler and Querengässer, 2019). In some specific contexts, expressive suppression has been observed to be adaptive in the short term (Harrington et al, 2020).

Second, it seems that during adolescence, there is also no relationship between cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, as reported by Cameron and Overall (2018) for adult and emerging adult respondents from New Zealand, Asia and Europe. These results are consistent and support the idea that the two dimensions of emotion regulation are distinct processes that operate differently in social interactions.

Third, the path analysis model shows that personality traits and the dimensions of emotion regulation have more robust linkages through extraversion and emotional stability, with small differences between adolescent boys and girls (Hypothesis 2). The values for explained variance are similar in all cases to those reported in prior research. However, prior studies used regression analysis, which could entail greater predictive error (Purnamaningsih, 2017; Sadr, 2016).

Among adolescents, extraverted girls tend to use resources that allow them to approach others to share experiences and feelings. Accordingly, they can increase their cognitive reappraisal strategies to manage their emotional resources in a more adaptive context and encourage closeness in interpersonal relationships (English et al, 2012). In adolescent boys and girls, extraversion can curb repressive and inhibitory strategies, which tend to be more maladaptive. Expressive suppression alludes to efforts to hide emotions, which can increase emotional problems and can affect the physical and emotional well-being of those who employ such strategies (Cameron and Overall, 2018), even though they can prove adaptive in traumatic situations (Gross, 2015; McRae and Gross, 2020). In general, repressing emotions can have negative consequences for people. Such consequences include more depressive moods, lower self-esteem, less life satisfaction and, in short, interpersonal costs (Cameron and Overall, 2018).

In contrast, antecedent-focused cognitive strategies that are activated before an emotional experience occurs enable people to manage emotional situations more effectively and to apply resources to communicate their emotional state. Such strategies thus discharge emotional energy effectively and offer relief for those who apply these strategies (Gross and Cassidy, 2019). In the period from adolescence to adulthood, behavioural patterns linked to personality traits change, in relation to the environment (Kawamoto and Endo, 2019; McCrae and Sutin, 2018). Moreover, adolescents seek a reference group with whom to build fluid interpersonal relationships that give them a sense of security. From this perspective, fostering extraversion and emotional stability through specific programmes could encourage the use of more adaptive strategies to maintain effective interpersonal relationships. It could also help people develop in a more balanced way, preventing them from distancing themselves from others during a stage in which relationships with peers are particularly important (Cameron and Overall, 2018).

In adolescence, intervention programmes should seek to enhance adaptive regulation strategies (Denissen et al, 2013), given that during this stage people mature and experience changes in their personality. Becoming more capable to express emotions can be positive on an intrapersonal and interpersonal level (Cameron and Overall, 2018). Therefore, it is important to understand the repercussions of personality traits for the process of emotion regulation (Eldesouky and English, 2019). This process is crucial during the transition from childhood to adulthood and therefore during adolescence (Perry et al, 2020). To the authors’ knowledge, there is no model that combines all personality traits during adolescence.

In conclusion, emotional stability and extraversion may be crucial for the use of strategies aimed at the reappraisal of emotional states and efforts to share emotional states and foster personal well-being (Gross and John, 2003). The results of this study provide new evidence of the relationships between personality traits and emotion regulation strategies, as well as under-explored aspects of emotion regulation related to sex differences during adolescence. Moreover, the study confirms the importance of considering personality traits in the process of emotion regulation in adolescents, as well as the small variations between girls and boys. Of the Big Five personality traits, among boys, only extraversion predicts expressive suppression (negatively) and only emotional stability predicts cognitive reappraisal. Among girls, both extraversion and emotional stability predict reappraisal and suppression. Extraversion is positively related to reappraisal strategies and negatively related to suppression, whereas emotional stability positively predicts antecedent-focused strategies (cognitive reappraisal).

Therefore, these findings can be valuable for the design of educational programmes for emotion regulation. Such programmes should encourage the communication of emotional states in a balanced, sincere and assertive way, especially in light of the unstable nature of personality traits during this stage of development. Therefore, it may be necessary to consider extraversion and emotional stability when designing more personalised intervention programmes. To the authors’ knowledge, no studies have yet offered such analysis.

This study has some limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study. This design prevents the identification of causal relationships, even though the statistical procedure of path analysis brings the results closer to explaining the effects of the antecedent variables of personality traits on the consequent variables of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression (Ato et al, 2013). Nonetheless, longitudinal analysis would lend greater substance to these findings. Second, the analysed variables were part of a broader study. They may therefore have been subject to a possible bias derived from response overburden, even though this situation was addressed by limiting the duration of the data collection sessions. Third, the study focused on middle adolescence (15 to 18 years), and respondents were mostly Spanish.

In future research, it would be of interest to extend the study to include other cultures in order to compare possible differences linked to cultural background. Such analysis was not possible in this study because of the high percentage of Spanish respondents (almost 93%). It would also be of interest to extend the study to include the period of transition from childhood to adolescence and to cover the whole period of adolescence in order to observe possible changes in personality traits (Borghuis et al, 2017; Kawamoto and Endo, 2019) and emotion regulation strategies (Stifter and Augustine, 2019). Another possible limitation relates to the brevity of the personality questionnaire used in this study. However, this questionnaire was chosen to reduce the response burden. Moreover, its reliability and internal validity have been widely confirmed, with studies revealing comparable psychometric performance to longer questionnaires (Gosling et al, 2003; Myszkowski et al, 2019).

This study shows that cognitive reappraisal strategies are positively associated with emotional stability, openness to experience, and extraversion, in both boys and girls. Adolescents who are more emotionally stable and open to new experiences tend to use more adaptive strategies to regulate their emotions. On the other hand, expressive suppression is negatively related to extraversion, as more extroverted adolescents are less likely to use this regulation strategy, which is generally associated with less adaptive social outcomes.

The analysis of the relationships between personality traits and emotion regulation strategies revealed that sex differences are not significant, although extraversion and emotional stability stand out as important predictors of cognitive reappraisal in both sexes. In girls, both extraversion and emotional stability predict cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, whereas in boys, extraversion predicts expressive suppression and emotional stability predicts cognitive reappraisal.

These findings have implications for the design of educational programs focused on emotion regulation, which should encourage balanced and assertive emotional expression, considering the changing nature of personality traits during adolescence.

The data used and analysed during this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

PD and AT designed the research study. PD and AT performed the research. MVM and AT provided help and advice. MVM made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. PD analysed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients or their relatives/legal guardians obtained informed consent for inclusion before participating in the study. According to Spanish Organic Law 3/2018 on the Protection of Personal Data and the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), research can be conducted once informed consent has been obtained from the participants or, in the case of minors, from their parents or legal guardians.

We sincerely appreciate the participation of the students, their families, and the educational institutions involved in the study.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.