1 Department of Social and Organizational Psychology, National University of Distance Education (UNED), 28040 Madrid, Spain

2 Department of Microbiology, University of Malaga, 29071 Malaga, Spain

Abstract

This review provides a foundational overview on the relationship between the gut microbiome (GM) and borderline personality disorder (BPD), first inquiring into the etiology of BPD, then examining the role of the GM and its microbial products on the pathophysiology of BPD, and finally exploring microbial associations with personality traits across childhood and adulthood.

A non-systematic, narrative approach is employed. The literature search was conducted across the PubMed and Scopus databases without restrictions on language and publication date.

The development of BPD is influenced by the interaction of biological and psychosocial factors, especially genetic predisposition and adverse childhood experiences. Specific gut microorganisms and their products play important roles in host mechanisms, modulating the host immune system, regulating inflammatory processes, and influencing brain function and behavior.

Current evidence indicates that the etiology and symptoms of BPD involve disruptions and imbalances within the GM, as it generates metabolites capable of influencing brain functions via pathways such as the vagus nerve and immune system. Undoubtedly, more studies will be necessary to establish further evidence on the role of the GM in BPD.

Keywords

- borderline personality disorder

- gut microbiome

- personality traits

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a psychological condition characterized by significant difficulties in emotional regulation and impulse control (Lieb et al, 2004; Rössler et al, 2022). As main symptoms, BPD often implies volatile emotional states, intense feelings of emptiness and impulsive conducts, which together can lead to maladaptation along with significant deterioration in psychosocial functioning, including suicidal behaviors and an increased risk of perpetrating acts based on physical and verbal violence (Esguevillas et al, 2018; Hughes et al, 2012; Neukel et al, 2022; Rössler et al, 2022; Scott et al, 2017).

The prodromal indicators that herald later personality disorders tend to present

during adolescence (Bozzatello et al, 2019). The development of BPD is

influenced by the interaction between biological factors and adverse early-life

experiences (Leichsenring et al, 2011; Lin et al, 2022). Exposure to

childhood trauma is related to subsequent alterations in the

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis response, including heightened cortisol

reactivity over the long term (Rinne et al, 2002; Watson et al, 2007).

Moreover, individuals with BPD exhibited significantly reduced hippocampal

volumes compared to matched controls (Sala et al, 2011). Changes in

opioidergic activity, including fluctuations in the ratio of the µ-

to

The human gut microbiome (GM) is composed by a diverse microbial community, with a population density of about 1011 to 1012 microbial cells/mL (Rinninella et al, 2019). It encompasses a wide array of microbial taxa, including archaea, bacteria, fungi, protozoa and viruses, with the bacterial domain being the most abundant (Borrego-Ruiz and Borrego, 2024a; Lloyd-Price et al, 2016). According to Kim et al (2021), more of 5000 prokaryotic species are included in the genomes of the human GM. Furthermore, the domain bacteria is composed by around 100 species that belong to the following eight phyla: Actinomycetota (formerly Actinobacteria), Bacillota (formerly Firmicutes), Bacteroidota (formerly Bacteroidetes), Campylobacterota, Fusobacteriota (formerly Fusobacteria), Pseudomonadota (formerly Proteobacteria), Thermodesulfobacteriota and Verrucomicrobiota (formerly Verrucomicrobia) (Reynoso-García et al, 2022; Rinninella et al, 2019; Ruan et al, 2020).

A lot of evidence has shown the connection between brain and gut through the vagus nerve and diverse chemical molecules (metabolites, hormones and neurotransmitters) (Bonaz et al, 2018; Fülling et al, 2019; Simpson et al, 2022). Specific gut microorganisms and their products play important roles in host mechanisms, modulating the host immune system (Belkaid and Hand, 2014; Zheng et al, 2020), regulating inflammatory processes (Blander et al, 2017; Clemente et al, 2018) and influencing brain function and behavior (Dinan et al, 2015; Huang et al, 2019). However, the alteration of the bacterial composition of the GM in BPD patients and its influence on the symptomatology of this disorder have been scarcely studied (Rössler et al, 2022).

Based on the potential implication of the human GM in the onset and development of several psychiatric and psychological disorders (Borrego-Ruiz and Borrego, 2024a), in the present narrative review we aim to provide a foundational overview on the relationship between the GM and BPD, addressing a topic that, to our knowledge, has not previously been specifically explored. For this purpose, this review first inquiries into the etiology of BPD, later examines the role of the GM and its microbial products on the pathophysiology of BPD, and finally explores microbial associations with personality traits across childhood and adulthood.

The present study employs a non-systematic, narrative review approach (Sukhera, 2022) primarily aimed at assessing existing literature on the relationship between GM and the pathophysiology of BPD, while also considering linked or potentially pertinent correlates. To ensure a comprehensive understanding of the current state of research on this topic, the information was gathered from a range of scientific studies related to the subject matter.

The search was conducted across the PubMed and Scopus databases to ensure access to a broad spectrum of articles without limitations on publication date. No language restrictions were applied, allowing for a potentially wider inclusion of studies, although the search keywords were limited to English terms. Keywords were selected and combined using Boolean operators. Specifically, the search strategy included diverse combinations with the following terms: (gut microbiome OR gut microbiota OR microorganisms) AND (borderline personality disorder) AND (personality traits) AND (pathophysiology OR influence OR symptomatology OR etiology) AND (childhood OR adulthood) AND (trials). Additionally, reference lists from prior studies were also reviewed to identify further articles of potential relevance.

The selection process involved an initial retrieval based on the predefined search criteria. Each article was subjected to a two-step screening process to ensure relevance. First, titles and abstracts were reviewed and studies not directly aligned with the research focus were excluded. Second, full-text assessments of the remaining articles were conducted to evaluate their pertinence to the objectives of the study, focusing on whether they provided substantial information.

Inclusion criteria were defined based on whether they examined the effects of GM on BPD, explored related physiological, neuropsychiatric, or psychological mechanisms, provided empirical or hypothetical insights into the process by which GM impacts on BPD, examined the etiology of BPD and factors linked to its onset and development, or offered relevant data on the microbial associations with various personality traits in childhood and adulthood. Exclusion criteria involved: (i) articles focusing on different mental disorders; (ii) articles focused on microbial infections; (iii) articles related to metabolic diseases; (iv) opinion articles, perspective articles, theses and proceedings; (v) articles lacking relevant or sufficient data.

The search and data extraction were conducted between June and July 2024. Articles considered irrelevant based on initial assessments and established criteria were excluded from the review and only those studies meeting all criteria and providing significant findings related to the central objectives of the study were retained and included in the review.

The biosocial developmental model of BPD (Crowell et al, 2009, 2014; Linehan, 1993), later evolved to a biopsychosocial model (Bozzatello et al, 2021; Lazzari and Rabottini, 2023), hypothesizes that this disorder is provoked by the interaction of biological and psychosocial factors, especially genetic predisposition (e.g., temperamental traits, genetic polymorphisms) and early life stress (e.g., different types of abuse, maladaptive parenting, trauma) (Anderson, 2020; Cattane et al, 2017; Leichsenring et al, 2011; Skodol et al, 2002; Winsper et al, 2017). Traumatic experiences may also be related to neuromorphological irregularities and to neuroendocrine fluctuations (i.e., HPA axis activation) that are detected in individuals with early BPD and a background of childhood adversities (Mainali et al, 2020).

Several studies show that BPD is moderately heritable, but no specific genes have yet been identified (Perez-Rodriguez et al, 2018; Sharp and Fonagy, 2015). A reduction in the size of the frontolimbic network, encompassing the orbitofrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex, is the main structural disturbance in both adolescents and adults with BPD (Sharp and Fonagy, 2015; Uzar et al, 2023). There is some evidence suggesting a possible link between altered amounts of neuropeptides, such as oxytocin and vasopressin, and the development of BPD (Stanley and Siever, 2010). Impairments in the functioning of the HPA axis, through the block or delayed release of cortisol (Guilé et al, 2018; Sharp and Fonagy, 2015), have also been observed in adolescents with BPD.

As noted above, several studies suggest that social factors play an important role within the etiology of BPD. Regarding the impulsive acts related to BPD, self-harm and suicidal behavior are recognized as core issues (Baus et al, 2014; Kaplan et al, 2016; Leichsenring et al, 2023; Nakar et al, 2016) and childhood traumatic events have been proposed as predictive factors for suicidality in BPD (Alberdi-Paramo et al, 2020; van Geel et al, 2014). Goodman et al (2017) found that approximately 90% of BPD patients reported self-harm and over 75% admitted to having attempted suicide, most commonly by overdose (over 50%). However, there are notable distinctions in self-aggressive behaviors between groups; adolescents with BPD are significantly more prone to frequent autolytic behaviors, whereas adults tend to report more suicide attempts.

Diverse studies have found a high concomitance of BPD in adolescent outpatients and inpatients with both internalizing (e.g., anxiety and depression) and externalizing (e.g., disruptive behavior and substance abuse) disorders, compared to adolescents without or with different personality disorders (Leichsenring et al, 2023; Norup and Bo, 2019; Shah and Zanarini, 2018). Currently, it is acknowledged that BPD occupies a unique position at the intersection of internalizing and externalizing disorders, possessing traits of both while not fitting squarely into either category and exhibiting in turn high comorbidity with both (Norup and Bo, 2019).

Temperamental traits and personality features in childhood and adolescence are early predictors of BPD (Bozzatello et al, 2019). There is a widespread agreement that temperamental vulnerability, coupled with childhood adversities, contribute to the development of traits associated with BPD (Bozzatello et al, 2021). The main traits identified in children and adolescents with BPD are aggression, emotional instability, excessive irritability, impulsiveness, low self-control and negative affectivity, which may predispose to the disorder in question (Belsky et al, 2012; Hecht et al, 2014). Vaillancourt et al (2014) found that aggressive behavior was a predictor of early diagnosis of BPD (at age 14) with gender variations, as relational aggression was the primary predictor for boys, whereas physical aggression was the most influential predictor for girls. Besides, it has been highlighted the negative emotional reactivity as another potential marker of vulnerability, strongly linked to family adversities, which can increase the risk of developing BPD symptoms (Stepp et al, 2016). Moreover, other studies have shown that emotional instability, impulsivity and low self-control, which are three closely related traits, can also be regarded as predictors of early-onset BPD (Gratz et al, 2009; Tragesser et al, 2010). Although there is evidence that temperamental traits could increase susceptibility to the development of BPD, said traits have to interact with aversive environmental factors to induce the disorder (Jovev et al, 2013). Maternal externalizing disorders, such as anxiety or depression during pregnancy, are epigenetic predictors also associated with early BPD in offspring (Conway et al, 2015).

Only one study has reported on the composition of the GM in BPD patients and in

its influence on the symptomatology of this disorder.

Rössler et al (2022) stated that there were no significant differences in

High levels of dysphoria, stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by the

BPD bidirectionally contribute to gut microbial dysbiosis and increase gut

permeability, resulting in an alteration of µ- and

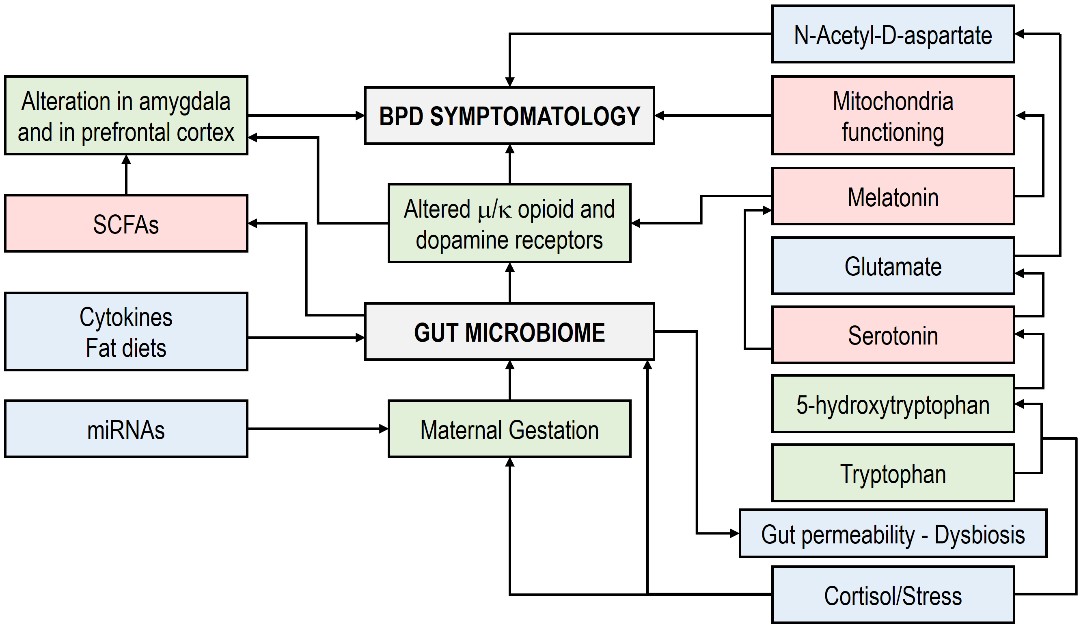

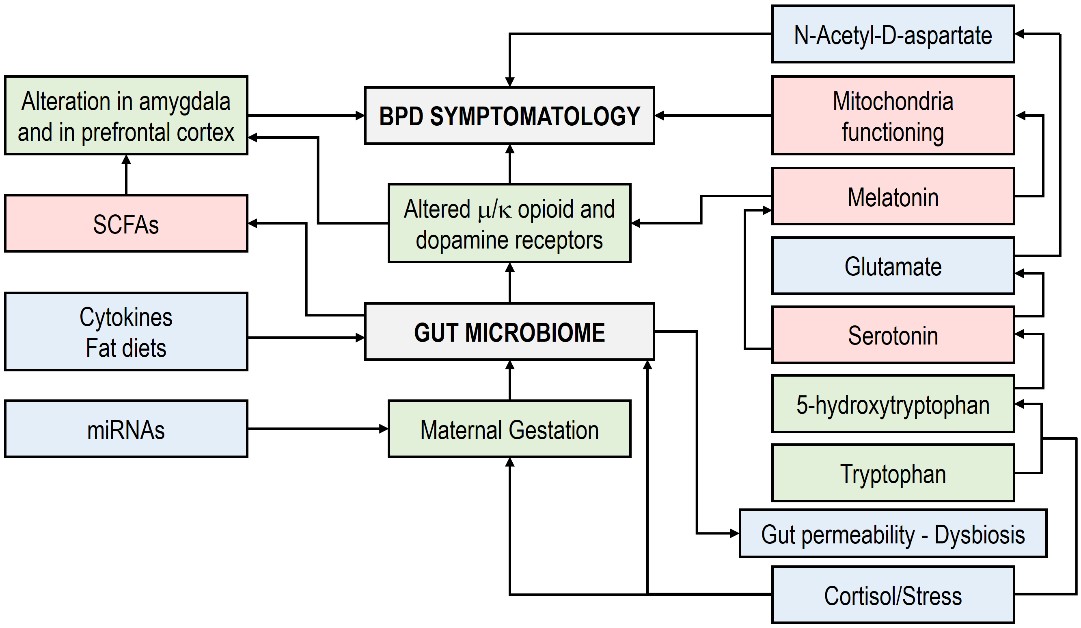

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Prenatal factors involved in the BPD susceptibility and symptomatology (modified from Anderson, 2020). Note: Rectangles in red, decrease; rectangles in blue, increase; rectangles in green, modulation/regulation. SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; BPD, borderline personality disorder.

Interestingly, Anderson (2020) proposed the existence of a link between prenatal factors and amygdala-prefrontal cortex interactivity, mediated by changes in the initial enteric development, the GM and the mucosal immune system. Therefore, the early developmental pathophysiology of BPD could be determined by prenatal processes affecting the GM and also linked to heightened levels in gut permeability and mucosal immunity. Multiple effects of the GM dysbiosis are influenced by a diminishment in the availability and in the uptake of butyrate, a GM-derived SCFA that has the capability to maintain the integrity of the gut barrier. Additionally, butyrate constitutes a histone deacetylase inhibitor, induces melatonin synthesis, optimizes mitochondrial functions and has immunosuppressive effects (Anderson and Maes, 2020).

Several studies have shown that SCFA-producing bacteria are less profuse in

individuals with mental disorders, including BPD (McGuinness et al, 2022; Rössler et al, 2022). SCFAs, a major product of microbial metabolism, are

generated when indigestible carbohydrates are fermented by gut bacteria,

including mainly acetate, propionate and butyrate. Thus, their production is

dependent on both diet and microbiota composition (Morrison and Preston, 2016). SCFAs are ligands for free fatty acid receptors 2 and 3 (FFAR 2/3), as

well as GPR109a, OR51E2 and PPAR

Modulation of the GM through diet or specific nutritional compounds has been identified as a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of various mental disorders (Borrego-Ruiz and Borrego, 2025). Multiple studies have been suggested that the supplementation of omega-3 fatty acid, or the adoption of diets rich in this fatty acid, significantly improves some symptoms associated with BPD, such as impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol, outbursts of anger and self-harm (Karaszewska et al, 2021; Zanarini and Frankenburg, 2003). Moreover, combined therapy of omega-3 with valproic acid has been found to be superior to monotherapy for controlling impulsivity in the treatment of BPD symptoms (Bellino et al, 2014; Bozzatello et al, 2018). Interestingly, omega-3 affects the GM of the subjects with BPD, inducing a decrease in the abundance of Faecalibacterium and an increase in the butyrate-producing bacteria belonging to the Lachnospiraceae family, bacterial taxa that produce anti-inflammatory compounds, such as SCFAs, which contributes to beneficial effects on inflammatory intestinal diseases (Costantini et al, 2017). Therefore, it can be stated that omega-3 fatty acid may exert a positive action on the intestinal wall integrity, interacting with host immune cells (Fu et al, 2021).

The initial microbiome of infants is formed by microbial transfer of the mother during and before birth (Walker et al, 2017). Multiple factors such as the way of delivery (vaginal or cesarean), gestation time, antibiotic exposure, diet, genetics, stress exposure and social and environmental interactions (Borrego-Ruiz and Borrego, 2024c; Laursen et al, 2021) influence the development of the infant microbiome, which is criss-crossed with early brain (Maiuolo et al, 2021) and immune system development (Sarkar et al, 2021). The GM stabilizes around the age of 3 years, aligning closely with that of young adults (Borrego-Ruiz and Borrego, 2024c). At this stage, its composition is mainly influenced by horizontal transmission, such as social interactions (Johnson, 2020). However, it continues to develop and change in accordance with different life stages.

Early infant GM composition is characterized by the predominance of the genus Bifidobacterium (based on milk diet), but as the infant begins to consume other foods (e.g., starch), the genus Bacteroides (and other Bacteroidota genera) increases due to a higher microbial diversity and richness of the GM. At 12 months, the GM community is dominated by Bacteroides and this fact has been linked to better cognitive development at 24 months (Carlson et al, 2018). Moreover, other genera are also important indicators of health (e.g., Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus), disease (e.g., several Pseudomonadota genera) and behavioral disturbances (e.g., Dialister and Veillonella) (Carlson et al, 2018, 2021; Loughman et al, 2020). In adults, the major microbial enterotypes, Bacteroides, Prevotella and Ruminococcus, have been stated to depend in part on the host’s long-term dietary pattern (Allen et al, 2017; Borrego-Ruiz and Borrego, 2025). Besides, these bacteria have been related to personality traits such as openness and to distinct forms of brain functioning, emotion processing and psychopathology predisposition (Lee et al, 2020).

Temperamental traits are considered to be at the core of personality and are associated with developmental psychopathology (Alving-Jessep et al, 2022; Bates et al, 2014). In infant at 18–27 months, the microbiome diversity is linked to surgency/extraversion (Christian et al, 2015), as well as to the relative abundance of Dialister and Ruminococcaceae (phylum Bacillota) and Parabacteroides and Rikenellaceae (phylum Bacteroidota). In other study, the abundance of Bifidobacterium and Streptococcus evaluated at 2.5 months was linked to later surgency evaluated at 6 months (Aatsinki et al, 2019). Furthermore, higher levels of Bifidobacterium and Enterobacteriaceae and lower levels of Bacteroides, were linked to emotional regulation (Aatsinki et al, 2019).

The role that plays the GM in modulating negative emotions can change depending mainly of diet and infant brain development. In neonates (25 days old), the abundance of Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum was related to negative emotional states, while emotional addressing was related to the abundance of B. pseudocatenulatum and B. catenulatum. However, higher Bifidobacterium and lower Clostridium levels were linked to reduced “fear bias” (i.e., attention directed to fearful versus happy/neutral faces) at 8 months of age (Aatsinki et al, 2022). In addition, in a pilot study composed of 34 infants at 1 year of age, Carlson et al (2021) found that a lower abundance of Bacteroides and a higher abundance of Veillonella, Dialister, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus and members of the order Clostridiales were significantly associated with increased fear-related behavior. Correspondingly, in a Chinese cohort study with participants of 12 months, Bifidobacterium was associated with soothability (Wang et al, 2020), whereas Hungatella was associated with decreased cuddliness (Sumich et al, 2022). In fact, several other bacterial families and species have been related to the fear response, such as Rikenellaceae (18–27 months) (Christian et al, 2015), Parabacteroides distasonis, Bilophila spp. and Roseburia intestinalis (5–7 years) (Flannery et al, 2020) and Lachnospiraceae and Bacteroides (5–11 year) (Callaghan et al, 2020). Moreover, Streptococcus salivarius has been linked to both emotional reactivity and externalizing behavior in children, while Akkermansia muciniphila has been associated with depression (Flannery et al, 2020). Table 1 shows microbial associations with several personality traits in childhood.

| Traits | Positive association | Negative association | Reference |

| Surgency/Extraversion | Dialister | Christian et al (2015) | |

| Parabacteroides | |||

| Rikenellaceae | |||

| Ruminococcacea | |||

| Bifidobacterium | Bacteroides | Aatsinki et al (2019) | |

| Enterobacteriaceae | |||

| Streptococcus | |||

| Emotional reactivity | Erwinia | Aatsinki et al (2019) | |

| Rothia | |||

| Serratia | |||

| Streptococcus | Flannery et al (2020) | ||

| Bifidobacterium | Aatsinki et al (2022) | ||

| Fear response | Rikenellaceae | Christian et al (2015) | |

| Atopobium | Aatsinki et al (2019) | ||

| Peptoniphilus | |||

| Bacteroides | Callaghan et al (2020) | ||

| Lachnospiraceae | |||

| Bilophila | Flannery et al (2020) | ||

| Parabacteroides | |||

| Roseburia | |||

| Bifidobacterium | Bacteroides | Carlson et al (2021) | |

| Dialister | |||

| Lactobacillus | |||

| Veillonella | |||

| Bifidobacterium | Clostridium | Aatsinki et al (2022) | |

| Depression | Akkermansia | Flannery et al (2020) | |

| Soothability | Bifidobacterium | Wang et al (2020) | |

| Cuddliness | Hungatella | Sumich et al (2022) |

In terms of adult personality, several pathobionts belonging to the phylum Pseudomonadota have been associated with neuroticism and even with major depressive disorder (Kiecolt-Glaser et al, 2015; Talarowska et al, 2020). In addition, conscientiousness was characterized by lower levels of members of Pseudomonadota and by higher abundance of the family Lachnospiraceae, which contain butyrate-producing bacteria associated with anti-inflammatory mechanisms (Kim et al, 2018). Bacterial diversity has been linked to agreeableness and openness, which may display a higher inclination regarding explorative behaviors and social proximity (Sumich et al, 2022). Johnson (2020) reported that sociability (a combined measure of extraversion, social skills and communication) was positively associated with Akkermansia, Lactococcus and Oscillospira (genera with anti-inflammatory properties), but negatively with Desulfovibrio and Sutterella (genera involved in systemic inflammation). Besides, the neurotic tendency (a combined measure of neuroticism, anxiety and stress) was found to be negatively associated with Corynebacterium and Streptococcus (Johnson, 2020). In older adults, Megamonas (a propionate producer) was negatively related to conscientiousness, neuroticism and openness and positively related to agreeableness, whereas Fusobacterium (a pathobiont) was negatively related to extraversion and openness (Renson et al, 2020).

Park et al (2021) found significantly lower microbial diversity

richness in the high anxiety and vulnerability group compared to the low anxiety

and vulnerability group. Additionally, there was significant difference between

low and high anxiety, self-consciousness, impulsivity and vulnerability groups

regarding to microbial

| Traits | Positive association | Negative association | Reference |

| Neuroticism | Haemophilus | Odoribacter | Kim et al (2018) |

| Corynebacterium | Johnson (2020) | ||

| Streptococcus | |||

| Megamonas | Renson et al (2020) | ||

| Pseudomonadota | Talarowska et al (2020) | ||

| Haemophilus | Park et al (2021) | ||

| Bifidobacterium | Jia et al (2023) | ||

| Desulfovibrio | |||

| Conscientiousness | Lachnospira | Pseudomonadota | Kim et al (2018) |

| Lachnospiraceae | |||

| Megamonas | Renson et al (2020) | ||

| Alistipes | Park et al (2021) | ||

| Sudoligranulum | |||

| Sociability | Akkermansia | Desulfovibrio | Johnson (2020) |

| Lactococcus | Sutterella | ||

| Oscillospira | |||

| Openness/Extraversion | Fusobacterium | Renson et al (2020) | |

| Happiness | Bifidobacterium | Jia et al (2023) | |

| Clostridium |

Several biological factors have been suggested to be associated with the onset and symptomatology of BPD, including various mechanisms dependent on the gut-brain axis. However, scarce research has been conducted to determine the role that the GM plays in the BPD pathophysiology. Regarding personality traits, the results obtained by recent studies are varied and difficult to compare with each other. Several confounding factors may explain this disparity, such as microbial sequencing techniques, dietary habits, geographic locations and lifestyle. Other aspects to consider in the reviewed studies are the small sample size and the different type of interventions, few of which have a longitudinal design. Due to these methodological shortcomings and the inconsistency of the results, we consider that the reviewed studies lack sufficient power to unambiguously identify the microbial taxa involved in specific personality traits. In this respect, this review emphasizes the considerable variability in how human GM data is collected and reported. Methodological variations in microbiome research significantly affect outcomes and the establishment of standardized practices, underscoring the need for transparent reporting and careful consideration of these limitations. Small sample sizes and absence of power calculation protocols for microbiome research make it difficult to determine whether studies are statistically strong to detect meaningful differences. Furthermore, factors such as dietary patterns, drug use, lifestyle habits and environmental exposures are strongly linked to shifts in the GM. Therefore, exhaustive data collection on these factors and their rigorous integration into analyses is essential for accurate interpretation.

Gut-brain research is prone to inconsistencies between studies on many levels, especially due to methodological divergences in the measurement of microbiota and of psychological function (Hooks et al, 2019). In fact, different bacterial species belonging to the same genus may differentiate some psychological functions. For instance, childhood impulsivity is positively related to Bacteriodes xylanisolvens, but negatively associated with B. fragilis (Gassen and Hill, 2019). For this reason, associations based on microbial metabolites, such as the production of SCFAs, bile acids, or pro/anti-inflammatory molecules, may be a more accurate predictor of the influence of biological factors on human behavior (Gassen and Hill, 2019). The relationship among GM and metabolomes, peptidomes, transcriptomics and brain function is yet unknown. Hence, the combined analysis of multi-omics will provide greater insight into GM framework. Despite lack of animal models close to humans, preclinical experiments are still crucial to identify the specific mechanisms of gut microbiota in personality traits and in BPD.

BPD is linked to significant functional impairment and, consequently, to an increased reliance on health services (Hughes et al, 2012; Leichsenring et al, 2011). While treatments such as dialectical behavior therapy, mindfulness training and psychodynamic therapy are recommended (Keefe et al, 2021; Kounidas and Kastora, 2022; Liakopoulou et al, 2023), pharmacological treatments have not been shown to improve the primary symptoms of BPD and reduce its severity (Gartlehner et al, 2021; Leichsenring et al, 2023). Empirical support through randomized controlled trials exists for various therapeutic approaches, including mentalization-based therapy, transference-focused therapy and schema therapy; however, none of them have established efficacy in controlled clinical trials regarding aspects such as hospitalization, recurrences, or suicidal behavior (Leichsenring et al, 2024). Thus, compared to standard psychiatric treatments, psychotherapy seems to be more effective, but there is a need for systematic clinical research on its application to BPD in order to show its true usefulness. Although pharmacotherapy does not consistently show efficacy for the core features of BPD and should be strictly limited, may be beneficial for treating determinate aspects of the clinical picture of this disorder and its comorbidities, including psychotic-like manifestations and eating disorders (Bozzatello et al, 2020; Pascual et al, 2023). Additionally, the application of psychobiotics seems to offer promising outcomes in the treatment of stress, anxiety and depression (Borrego-Ruiz and Borrego, 2024b), which are often concomitant symptoms of BPD. Addressing BPD through nutritional interventions may benefit from a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids, as it has been suggested its efficacy in alleviating BPD symptoms (Karaszewska et al, 2021). Plant-based diets, rich in fiber, antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds, contribute to a healthy GM, potentially alleviating BPD symptoms through reduced inflammation and modulation of the gut-brain axis (Borrego-Ruiz and Borrego, 2025). In this regard, plant-based diets that include omega-3-rich nutritional components, along with ongoing psychotherapy and supplementation with psychobiotics, may represent a potential therapeutic approach to help mitigate adverse symptoms of BPD and other psychological comorbidities. Nevertheless, further research is required to assess the effects of dietary components and the efficacy of such integrated therapies.

Early diagnosis and intervention will be pivotal for reducing both personal suffering and societal costs associated with BPD. Research indicates that BPD patients tend to have lower expectations of social acceptance and to adjust their behavior less cooperatively following positive social feedback (Liebke et al, 2018). This altered response to social acceptance can hinder the formation of stable, cooperative relationships, adversely affecting future interpersonal interactions, including those related to the clinical context. Moreover, intentional harm by peers during childhood may serve as a precursor to developing BPD (Sansone et al, 2010; Wolke et al, 2012). A possible way to address this issue is to investigate the emotional experience of bullying victims from a psychosocial perspective, with the objective of gaining a greater understanding of the key factors involved, which could contribute to the development of tools aimed at mitigating the emotional trauma associated with bullying victimization (Borrego-Ruiz and Fernández, 2024). Furthermore, it is essential for clinicians to be trained in order to inquire about and also to deal with, adverse peer experiences in mental health assessments and interventions.

The present review identifies several limitations that need to be considered when interpreting its results. First, regarding the central objective of the review, it was found only one study on the relationship between the GM and BPD, which is exiguous evidence to infer causality on this specific link. Second, the geographical variation in sample origins may have introduced bias, as distinct regions are likely to exhibit different microbial profiles, potentially influencing the outcomes. Third, while this review primarily focused on research examining the bacterial components of the GM, it is important to note that the gut harbors a diverse array of microorganisms, including archaea, viruses, protozoa and fungi, all of which could exert influence on host mental health, including BPD. Fourth, the use of 16S rRNA gene sequencing has inherent limitations, such as reduced resolution and sensitivity, which may affect the reliability of microbiome composition data. In this regard, as the field advances, the integration of other omics techniques such as metagenomics, metabolomics and meta-transcriptomics will likely provide a more comprehensive understanding of the GM, extending beyond its bacterial composition, which could offer valuable benefits for psychiatry and psychology, disciplines that still lack biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and a clear etiological framework for several mental disorders. Finally, our synthesis may be influenced by unaccounted confounders, as the data collected from the studies varied considerably and few studies accounted for potential confounding variables in their analyses.

BPD is a mental health condition influenced by multiple factors. Current evidence indicates that its etiology involves disruptions and imbalances within the gut microbial ecosystem, which forms the structural basis for the association between BPD and the gut-brain axis. The symptom fluctuations observed in individuals with BPD are considered to be associated with the GM, as it generates metabolites capable of influencing brain functions via pathways such as the vagus nerve and immune system. Thus, identifying specific GM types and elucidating their mechanisms of action in BPD is essential for advancing future treatment approaches. Undoubtedly, more studies will be necessary to establish further evidence on the role of GM on BPD.

Conceptualization, AB-R and JJB; Investigation, AB-R and JJB; Writing—Original Draft, AB-R and JJB; Writing—Review and Editing, AB-R; Supervision, JJB. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.