1 Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Extremadura, 06006 Badajoz, Spain

Abstract

Psychological violence is the most common form of aggression in intimate partner relationships. The lack of agreed theoretical explanations and instruments to identify its multiple manifestations hinders early detection and effective intervention against psychological violence. Therefore, the present study aims to design and validate an instrument for measuring psychological violence in relationships and to determine its psychometric properties.

The study was carried out with 684 university students, 389 females and 295 males, aged between 17 and 23 years (M = 19.8; SD = 2.58). Different sources of validity for The Questionnaire on Psychological Violence in Intimate Partner Relationships (CVPPar) were analysed.

First, the factor structure was determined. The results of the exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis supported the 46-item, seven-factor structure for CVPPar. This structure accounted for 83.39% of the variance explained. Furthermore, reliability was examined showing a high internal consistency (α = 0.955; ω = 0.957). Finally, CVPPar scores were found to correlate with the CTS-2 and BSI-18.

The study concludes that CVPPar has optimal and robust psychometric properties for the assessment of manifestations of psychological violence in intimate partner relationships.

Keywords

- psychological violence

- couple relationships

- validation

- questionnaire

- psychometric properties

Psychological violence is currently the commonest form of aggression in intimate partner relationships (Dokkedahl et al, 2022). There are numerous studies that recognise the especially pernicious nature of this phenomenon. Such assertions are based on findings that point towards psychological violence being not only the predecessor of other typologies, but also on the impact it has on the physical and mental health of the individual, through which the victims’ deterioration equals or even surpasses that of physical and sexual violence (Carreño, 2017; Doyle, 2020; Gabster et al, 2022; Kanemasa et al, 2022).

Among the psychological consequences of this type of violence, of particular importance are anxiety and depression, low self-esteem, social and family isolation, emotional dependence, insecurity, submission, and a lack of social adaptation. In addition, it is also related to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the consumption of toxic substances and/or drugs, and suicidal tendencies (Chust-Morató et al, 2021; Dokkedahl et al, 2022; Esteves-Pereira et al, 2020; Rowther et al, 2023).

The lack of any agreed theoretical explanatory approaches concerning psychological violence, together with the absence of evaluation instruments and techniques, which would allow us to identify its diverse manifestations, constitutes a problem that severely hinders early detection and any consequent intervention when faced with such situations (Jaramillo-Correa et al, 2023).

It would thus seem that the first challenge in order to establish healthy relationships between couples is to exhaustively define psychological violence in its diverse manifestations. This is an arduous task, not only because of the multidimensional nature of the indicators present from the start, but also because of the normalization process to which it is currently subjected. Although we must stress the subtle forms that such violence can take on when it appears and becomes an integral part of the couple; we cannot forget the socio-cultural recognition that surrounds it due to the idealised model of romanticism that reigns still in our society (Fedele et al, 2019; Martín and Moral Jiménez, 2019).

Despite these difficulties that lead to psychological violence being the least studied form of aggression, there are theoretical approaches whose aim is to throw light on the concept. The idea most commonly accepted is that psychological violence can be understood as any form of conduct that causes the destruction of or emotional harm to an individual, damaging their personal development, either visibly or invisibly, through coercive tactics (Molina et al, 2014; Páramo et al, 2021; Tutiven-Abad et al, 2022; Vidal et al, 2024).

The greatest disagreement seems to lie in the mechanisms used to do so. Initially, O’Leary (1999) stated that psychological violence was exercised through such acts as recurrent criticism, verbal aggression and attacks towards the partner’s self-esteem. This definition set the basis for other, more recent definitions that stress the role of verbal aggression that harms the individual’s psychological stability, but without ignoring the importance of non-verbal expressions as a form of exercising violence through omission (Olivera-Carhuaz et al, 2022). Similarly, Colque (2020) and Tourné et al (2024) agree with the above definition, in that the destruction of the other’s self-esteem is a key means to inflicting psychological abuse. However, they add elements which they consider to be of equal relevance, such as generating feelings of guilt in the partner through intimidation and making them feel valueless.

There are many classifications of the manifestations of psychological violence which stress the indicators of a most generic psychological and verbal nature; even though reality teaches us that it is a complex phenomenon that can either have the clearest of evidence or only the slightest of visible manifestations (Villavicencio-Aguilar and Jaramillo-Paladinez, 2020).

Taverniers (2001), for his part, presents a categorization of the manifestations of psychological violence that offers a high level of exactitude when describing its forms of expression. She points out that psychological violence in intimate partner relationships can show itself through acts that make the victim fell valueless, invalidating the victim’s reality through ridicule, disqualification, trivialization, constant opposition and disdainful attitudes towards the other (Güleç and Özbay, 2024). Furthermore, she contemplates such behaviour patterns as reproaches, considered to be one of the most frequent forms of violence, insults and threats. She also takes into account less evident manifestations, such as a lack of empathy and support, indifference, and monopolising the victim’s interests, opinions or needs.

In the classification, Taverniers (2001) also incorporates behaviour that intimidates the victim on a verbal level (judging everything they do or say, criticising them for not thinking in the same way, and constantly correcting them), as well as through the expansive and violent use of the physical space (threatening postures and gestures and destructive behaviour aimed at objects of sentimental value or pets). His classification also includes one of the most destructive mechanisms of psychological violence: “gaslighting”. Here, the aggressor makes the victim doubt their own perceptions, their memory and even their mental health, negating or distorting the facts and accusing the victim of lying, imagining and inventing facts, and blaming them (Arabi, 2023; Huang et al, 2024). The imposition of behaviour is also considered by the author as a mechanism for exercising psychological violence, as an attempt to obtain absolute control over the victim, blocking social interaction. Similarly, in order to set these violent mechanisms in motion, aggressors can simulate love, interest and concern for the victim, in an attempt to justify their actions with the label of “apparent kindness”, which masks the implicit violence of abusive acts, generating profound emotional damage in the victim (Martínez et al, 2024).

On the basis of the above, the creation of an evaluation instrument to detect and measure psychological violence in intimate partner relationships is crucial if we wish to prevent it and achieve an effective treatment. There is currently no agreed definition of psychological violence that takes into account both its clearest manifestations (verbal attacks such as insults, threats, reproaches, orders, destructive behaviour…) and the least visible ones (gaslighting, negation, apparent kindness, trivializations, deflections, abusive insistence…). Neither are there precise evaluation techniques in the context of psychological violence within intimate partner relationships that can allow us to identify such manifestations with sufficient exactitude and detail.

It is also true that such instruments which have been created and used to evaluate psychological violence are aimed at measuring the general nature of the violence within the couple’s relationship, or within the context of gender related violence (Heise et al, 2019; Tourné et al, 2024). Most of the available instruments include psychological violence as a subscale, together with physical violence and sexual abuse. This could be considered the case of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2), by Straus et al (1996), one of the most commonly used scales in the sphere of intimate partner violence to measure psychological abuse; it also contemplates negotiation, physical aggression, sexual coercion and injuries. However, it does not include such important manifestations of psychological violence as trivialization, humiliation, indifference, intimidation (judging, criticising and correcting), manipulating reality, behavioural impositions (deflections) or even (gaslighting). Nevertheless, it is still an instrument of reference and remains one of the most commonly used.

In addition, there are other instruments of great impact, such as the Index of Spouse Abuse (ISA), proposed by Hudson and McIntosh (1981), which evaluates violence within couples, and in particular the magnitude and severity of the psychological aggression. However, it only contemplates a limited number of violent behaviour patterns. We should also mention other instruments, such as the Abuse Behavior Inventory (ABI), by Shepard and Campbell (1992), which does include such categories of psychological abuse as humiliation, isolation, intimidation and economic abuse. It also contemplates physical abuse, as it was originally designed for abusers.

As for specific measures, we should mention the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (PMWI), by Tolman (1989), which focused on evaluating control through Dominance/Isolation and Emotional/Verbal Abuse. Nevertheless, it was originally designed for women who had suffered psychological maltreatment by their male partners. We should also mention Marshall’s Subtle and Overt Psychological Abuse of Women Scale (SOPAS) (2000, as cited in Buesa and Calvete, 2011), which, although it does contemplate a wider range of abusive behaviour, is an instrument validated and aimed exclusively at the female population.

A review of the most relevant scales or inventories used, both nationally and internationally, to analyse psychological violence reveals the need to create an instrument that can measure this phenomenon in both an integral and bidirectional way. That is, considering that psychological violence can be perceived from the perspective of both members of the couple and not only from the prism of gender.

Thus, the objective of this paper is to construct and validate psychometrically the Questionnaire on Psychological Violence in Intimate Partner Relationships (“Cuestionario de violencia psicológica en la pareja”, CVPPar). We analyse the validity of the questionnaire’s construct, confirming its reliability and examining the convergent validity with respect to other psychological measures. Unlike the reviewed instruments, the questionnaire is expected to allow psychological violence within couples to be evaluated independently of the member exercising said violence, considering the ample and complex spectrum of manifestations it presents and the subtle or overt nature of the same (Arabi, 2023).

The sample is made up of 684 students from the University of Extremadura (Spain); 389 female (56.9%) and 295 male (43.1%), between 17 and 23 years of age (M = 19.8; SD = 2.58). A non-probability convenience sampling was performed within various different university degree courses: Psychology (34.79%), Health Sciences & Medicine (15.64%), Enterprise Administration & Management, Economics & Labour Relations & Human Resources (6.58%), Sciences (29.97%), Documentation & Communication Sciences (2.78%), and Engineering (10.24%). The participants in the study came from families with a medium cultural and socioeconomic level as far as income, studies and work situation are concerned.

(a) Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2; Straus et al, 1996),

Spanish version by Graña et al (2013). This instrument evaluates the

degree to which the members of an intimate partner relationship use physical or

psychological violence against the other, as well as the use of negotiation and

reasoning to resolve conflicts. It consists of 78 items organized in a double

question format, one as perpetrator and the other as victim. It has five

subscales: (1) Negotiation with 6 items (“I showed my partner I cared even

though we disagreed”, “My partner showed care for me even though we

disagreed”); (2) Physical aggression with 12 items (“I twisted my partner’s arm

or hair”, “My partner did this to me”); (3) Psychological abuse with 8 items

(“I shouted or yelled at my partner”, “My partner did this to me”); (4)

Sexual coercion with 7 items (“I insisted on sex when my partner did not want to

(but did not use physical force)”, “My partner did this to me”); and (5)

Injuries with 6 items (“I passed out from being hit on the head by my partner in

a fight”, “My partner passed out from being hit on the head in a fight with

me”). The response format goes from 1 (once in the past year) to 6 (more than 20

times in the past year). It also includes the values 7 (not in the past year, but

it did happen before) and 0 (this has never happened). Correction and

interpretation is done through three criteria (frequency, prevalence and severity

of physical violence). The frequency score is obtained by adding the scores of

the items in each subscale. The prevalence score is considered if some of the

behaviours included in the subscales are present or not, giving them a value of 0

(absent) and 1 (present), except for the Negotiation subscale. And the severity

score is obtained by summing the responses of the Physical aggression subscale.

The internal consistency (Cronbach’s

(b) Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18; Derogatis, 2001), Spanish

version by Departamento de I+D de Pearson Clinical y Talent Assessment (2013).

This is the abbreviated version of Symptoms Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R;

Derogatis, 1994) and Brief

Symptoms Inventory (BSI; Derogatis and Melisaratos, 1983)

The BSI-18 was designed to evaluate the suffering or

psychological distress of the person at that particular time, as well as the

psychopathological symptoms in the general and medical population. The temporal

timeframe it covers is the previous seven days, giving an indication of the

degree of distress caused by each of the symptoms presented. It is made up of 18

Likert type items that evaluate three symptomatic dimensions of psychopathology:

(1) Somatization with 6 items (“Faintness or dizziness”); (2) Depression with 6

items (“Feeling no interest in things”); and (3) Anxiety with 6 items

(“Nervousness or shakiness inside”); and a Global Distress Index (GSI-Global

Severity Index). There are five options to respond: 0 (none), 1 (a little), 2

(moderately), 3 (quite a lot) and 4 (a lot). Correction is made by summing the

responses for each symptomatic dimension and the total of the items for the

global index. The scores are then converted into percentile scores and compared

with the scale tables to determine the high, low or normality of each dimension.

The internal consistency (Cronbach’s

(c) Questionnaire on Psychological Violence in Intimate Partner

Relationships (“Cuestionario de violencia psicológica en la pareja”,

CVPPar). This instrument has been developed in this study in order to evaluate

the different manifestations of psychological violence in intimate partner

relationships, based on the indicators described by Taverniers (2001). It

consists of 46 Likert type items aimed at detecting manifestations of

psychological violence from seven factors: (1) Devaluation with 10 items (“My

partner makes fun of me in public and then says it was a joke”); (2) Hostility

with 6 items (“My partner threatens to hurt him/herself if I leave him/her”);

(3) Indifference with 4 items (“My partner is not willing to adapt to my needs

and expectations”); (4) Intimidation with 6 items (“My partner constantly

corrects me whatever I do”); (5) Imposition of behaviour with 12 items (“My

partner does not want me to do activities that could help me advance in any

sphere of my life”); (6) Blaming with 6 items (“My partner denies having said

things that she/he did say to me”); and (7) Apparent kindness with 2 items (“My

partner says he/she insults me so I can learn how to do things well”). The scale

consists of possible responses corresponding to the degree of agreement or not

with the statement: 0 (never), 1 (rarely), 2 (sometimes), 3 (frequently) and 4

(always). Correction is made by adding up the responses in each factor to obtain

partial scores for the manifestations of psychological violence. Similarly, the

total score is obtained by summing the responses to the total number of items,

where a higher score indicates a greater presence of manifestations of

psychological violence in intimate partner relationships. The internal

consistency (Cronbach’s

The study was carried out in different stages. The first was a bibliographical review of the state-of-the-art and of the national and international scales commonly utilised to provide internal coherence to the instrument. Then, given the lack of any specific validated instrument for the screening or diagnosing of psychological violence in intimate partner relationships in its own right in Spain which contemplates subtle and overt manifestations in both the male and female populations, we proceeded to build the CVPPar instrument on the basis of the model for psychological violence proposed by Taverniers (2001). The items were created and clearly and precisely formulated on the basis of our own conceptual analysis of the model. We took into account linguistic factors and possible cultural differences, with the objective of making them capable of evaluating psychological violence in intimate partner relationships.

Having completed the questionnaire, we requested authorization from the pertinent university authorities of the faculties that were to participate in the research. They were informed of the study’s content and aims. We then informed the lecturers and proceeded to administer the different instruments. The students gave their consent to participation in the study and received information beforehand concerning it, as well as concerning their right to stop participating at any time. The instruments were applied collectively, ensuring anonymity and data confidentiality. The time taken to complete the tests was approximately 45–50 minutes. The evaluators were present at every moment during the implementation of the instruments to resolve doubts and check that the questionnaires were correctly completed, it being necessary to answer all the items.

All the procedures carried out complied with the directives concerning their adaptation to the International Test Commission (ITC; Hambleton, 2001), as well as to the ethical standards of the University of Extremadura (Ref.: 92/2020) and to the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later modifications or comparable ethical standards.

The data analysis was carried out using the statistical programme SPSS version 27.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and Jamovi version 2.3.21 (The jamovi project, Sydney, Australia).

A descriptive analysis was first carried out using the subjects’ responses to the CVPPar instrument in order to organise, summarise and analyse the information collected concerning the manifestations of psychological violence in intimate partner relationships.

We then proceeded to check the construct’s validity by means of factorial

analysis to find the minimum number of dimensions capable of explaining the

highest percentage of information contained within the data. The sample was

randomly divided into two equal halves (n = 342) and (n = 342)

respectively. We then performed the exploratory factorial analysis (EFA) of the

data from subsample 1 to look for a structure within the data and to examine the

underlying dimensions of the observed variables in greater detail. Principal

components was selected as the factorial extraction method in order to maximise

the explained variance. The rotation criterion chosen to reduce the number of

high-weight factors in a factor was Varimax. Additionally, one aspect to be taken

into account is that the selected items should be those that present the highest

factorial weights and the greatest item-dimension correlations. We then performed

the confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA) for the data of subsample 2. To do so,

we used the Jamovi (2.3.21) programme. The maximum verisimilitude method was used

to perform the CFA, and such indices as the

Having obtained the final model, the reliability was found through internal

consistency via Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega. A result between 0.70 and

0.80 is considered an acceptable coefficient, while 0.80 to 0.90 is an indicator

of good internal consistency, with values

Finally, evidence of convergent validity was obtained by means of Pearson’s correlations between the CVPPar and the CTS-2 and BSI-18 tests.

The descriptive analysis of the CVPPar demonstrated that the scores of the participants ranged from 0 to 4. The highest average score was for item 6 (M = 3.06; SD = 0.950) in the dimension Indifference, showing manifestations of a lack of empathy and support, as well as monopolization. The lowest score corresponded to item 43 (M = 1.03; SD = 0.492) in the dimension Apparent kindness. In turn, the asymmetry and kurtosis coefficients were calculated in order to examine the distribution of the items (Table 1).

| Factors and items | M | SD | Asymmetry | Kurtosis | |

| Devaluation | 2.01 | 0.617 | –0.067 | –1.693 | |

| Item 1 | 2.28 | 0.601 | 0.465 | 1.138 | |

| Item 5 | 2.44 | 0.873 | –0.641 | 1.286 | |

| Item 9 | 2.02 | 0.765 | –0.758 | 1.179 | |

| Item 10 | 2.85 | 1.051 | –0.142 | 0.153 | |

| Item 14 | 1.21 | 0.572 | 0.367 | 1.002 | |

| Item 15 | 1.25 | 0.658 | 0.379 | 1.159 | |

| Item 17 | 2.73 | 0.987 | –0.273 | 0.995 | |

| Item 19 | 2.32 | 0.733 | –0.927 | 1.077 | |

| Item 27 | 1.4 | 0.730 | 0.547 | 1.077 | |

| Item 28 | 1.5 | 0.850 | –0.964 | 1.395 | |

| Hostility | 1.86 | 0.336 | –0.951 | 1.587 | |

| Item 4 | 2.1 | 0.527 | 0.246 | 1.174 | |

| Item 8 | 1.48 | 0.885 | 0.542 | 1.164 | |

| Item 13 | 2.01 | 0.989 | 0.626 | 1.219 | |

| Item 23 | 2.16 | 0.509 | 0.314 | 1.314 | |

| Item 24 | 1.83 | 0.617 | 0.374 | 1.294 | |

| Item 29 | 2.11 | 0.395 | 0.278 | 1.376 | |

| Item 47 | 1.31 | 0.809 | –0.852 | 1.114 | |

| Indifference | 1.8 | 0.614 | 1.129 | 0.276 | |

| Item 6 | 3.06 | 0.950 | 0.589 | 1.281 | |

| Item 12 | 2.15 | 0.880 | 0.511 | 1.289 | |

| Item 25 | 1.48 | 0.925 | –0.454 | 1.182 | |

| Item 37 | 1.1 | 0.691 | 0.419 | 1.147 | |

| Item 48 | 1.21 | 0.599 | –1.318 | 1.148 | |

| Intimidation | 2.08 | 0.590 | –1.941 | 1.394 | |

| Item 2 | 2.11 | 0.770 | 0.662 | 1.189 | |

| Item 16 | 2.19 | 0.532 | 2.236 | 1.355 | |

| Item 20 | 2.04 | 0.311 | 3.344 | 1.317 | |

| Item 32 | 1.24 | 0.574 | 0.418 | 1.050 | |

| Item 39 | 2.06 | 0.241 | 0.248 | 1.294 | |

| Item 40 | 2.36 | 0.608 | 0.328 | 1.169 | |

| Imposition of behaviour | 1.54 | 0.587 | 0.462 | –1.270 | |

| Item 3 | 1.53 | 0.907 | –0.518 | 1.038 | |

| Item 7 | 2.01 | 0.627 | 1.013 | 1.215 | |

| Item 11 | 2.14 | 0.567 | 0.246 | 1.046 | |

| Item 18 | 2.06 | 0.259 | 0.231 | 1.165 | |

| Item 22 | 1.32 | 0.807 | 0.396 | 1.171 | |

| Item 26 | 1.36 | 0.715 | 0.503 | 1.010 | |

| Item 30 | 1.46 | 0.882 | 0.521 | 1.137 | |

| Item 31 | 1.3 | 0.787 | 0.343 | 1.045 | |

| Item 34 | 1.22 | 0.557 | 0.394 | 1.078 | |

| Item 42 | 1.04 | 0.856 | 0.514 | 1.233 | |

| Item 44 | 1.06 | 0.909 | 0.506 | 1.175 | |

| Item 45 | 1.49 | 0.796 | 0.615 | 1.117 | |

| Item 50 | 2.01 | 0.498 | 0.200 | 1.031 | |

| Blaming | 1.71 | 0.619 | 1.099 | 0.649 | |

| Item 21 | 1.58 | 0.953 | 0.608 | 1.016 | |

| Item 33 | 2.85 | 0.722 | 1.028 | 1.026 | |

| Item 35 | 1.85 | 0.575 | 1.017 | 1.105 | |

| Item 36 | 1.18 | 0.606 | 0.297 | 1.284 | |

| Item 38 | 2.13 | 0.480 | 0.270 | 1.110 | |

| Item 46 | 1.21 | 0.631 | 0.332 | 1.124 | |

| Item 49 | 1.2 | 0.656 | 0.304 | 1.292 | |

| Apparent kindness | 1.53 | 0.664 | 0.380 | 0.651 | |

| Item 41 | 1.97 | 0.294 | 0.170 | 1.045 | |

| Item 43 | 1.03 | 0.492 | 0.223 | 1.082 | |

Below are the findings with respect to the results obtained from the validated instrument.

As for the gender differences among the participants, we observed significant differences for the scores in the Devaluation, Intimidation and Imposition of behaviour factors, with higher scores for females. However, no statistically significant differences were found in the Hostility, Indifference, Blaming and Apparent kindness factors.

When comparing for age groups of 17 to 20 and 21 to 23 years, significant differences were obtained for the scores of the Devaluation, Imposition of behaviour and Blaming factors, with higher scores in the older group. No statistically significant differences were found in the remaining factors.

The results also show that there were no statistically significant differences between the results of the factors of the CVPPar and the socioeconomic level (Table 2).

| Subescales of CVPPar | Gender | Age (years) | Socioeconomic level | |||||||||||

| Women | Men | 17–20 | 21–23 | Low | Medium | High | ||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Devaluation | 2.16* | 0.637* | 1.84* | 0.575* | 1.65* | 0.623* | 2.37* | 0.599* | 1.87 | 0.424 | 2.11 | 0.619 | 1.32 | 0.617 |

| Hostility | 1.91 | 0.391 | 1.85 | 0.283 | 1.88 | 0.353 | 1.85 | 0.312 | 1.85 | 0.206 | 1.89 | 0.366 | 1.43 | 0.336 |

| Indifference | 2.09 | 0.919 | 1.50 | 0.682 | 1.82 | 0.820 | 1.77 | 0.799 | 1.73 | 0.735 | 1.91 | 0.857 | 1.37 | 0.814 |

| Intimidation | 2.21* | 0.371* | 1.79* | 0.412* | 2.01 | 0.389 | 2.09 | 0.370 | 1.95 | 0.315 | 2.10 | 0.347 | 1.41 | 0.390 |

| Imposition of behaviour | 1.75* | 0.441* | 1.31* | 0.294* | 1.19* | 0.473* | 1.96* | 0.264* | 1.48 | 0.314 | 1.66 | 0.477 | 1.15 | 0.387 |

| Blaming | 1.72 | 0.629 | 1.69 | 0.602 | 1.51* | 0.630* | 1.99* | 0.587* | 1.55 | 0.323 | 1.81 | 0.585 | 1.22 | 0.619 |

| Apparent kindness | 1.54 | 0.686 | 1.51 | 0.643 | 1.55 | 0.651 | 1.51 | 0.665 | 1.37 | 0.345 | 1.59 | 0.614 | 1.09 | 0.664 |

Note: *p

The EFA has allowed us to examine the instrument’s underlying structure in

greater detail. To do so, we first of all checked compliance with the criteria

concerning the viability of applying the EFA. The indices obtained (correlation

matrix determination of 0.001; Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin = 0.905; Bartlett’s sphericity

test with significance p

The analysis establishes that the communalities are situated between 0.732 and 0.906, making the test both adequate and reliable. We then carried out a principal components factorial analysis with Varimax rotation. The factorial solution resulted in seven factors with 83.39% of the variance explained. Thus, from the rotated factors of the matrix and the factorial weight of each one of the items, it can be observed that they have factorial loads above 0.30, being grouped into seven factors. In this sense, the items with loads above 0.30 that appear in more than one factor have been placed taking into account the higher factorial load, given the selected orthogonal procedure (Varimax). On the other hand, we considered eliminating those elements with factorial loads below 0.30. Thus, the items 23, 36, 48 and 50 were excluded from the CVPPar (Table 3).

| Items | Components | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Item 19 | 0.830 | ||||||

| Item 1 | 0.810 | ||||||

| Item 14 | 0.783 | ||||||

| Item 9 | 0.765 | ||||||

| Item 28 | 0.751 | ||||||

| Item 17 | 0.748 | ||||||

| Item 5 | 0.726 | ||||||

| Item 10 | 0.627 | ||||||

| Item 27 | 0.614 | ||||||

| Item 15 | 0.611 | ||||||

| Item 4 | 0.857 | ||||||

| Item 8 | 0.734 | ||||||

| Item 24 | 0.722 | ||||||

| Item 29 | 0.697 | ||||||

| Item 13 | 0.660 | ||||||

| Item 47 | 0.551 | ||||||

| Item 23 | |||||||

| Item 25 | 0.901 | ||||||

| Item 37 | 0.867 | ||||||

| Item 6 | 0.858 | ||||||

| Item 12 | 0.796 | ||||||

| Item 48 | |||||||

| Item 39 | 0.831 | ||||||

| Item 16 | 0.819 | ||||||

| Item 2 | 0.794 | ||||||

| Item 20 | 0.776 | ||||||

| Item 40 | 0.711 | ||||||

| Item 32 | 0.702 | ||||||

| Item 34 | 0.812 | ||||||

| Item 31 | 0.801 | ||||||

| Item 11 | 0.788 | ||||||

| Item 26 | 0.786 | ||||||

| Item 7 | 0.782 | ||||||

| Item 30 | 0.752 | ||||||

| Item 42 | 0.730 | ||||||

| Item 18 | 0.724 | ||||||

| Item 44 | 0.724 | ||||||

| Item 22 | 0.661 | ||||||

| Item 3 | 0.653 | ||||||

| Item 45 | 0.617 | ||||||

| Item 50 | |||||||

| Item 35 | 0.827 | ||||||

| Item 49 | 0.816 | ||||||

| Item 38 | 0.793 | ||||||

| Item 21 | 0.780 | ||||||

| Item 46 | 0.750 | ||||||

| Item 33 | 0.707 | ||||||

| Item 36 | |||||||

| Item 41 | 0.906 | ||||||

| Item 43 | 0.853 | ||||||

Note: 1 = Devaluation; 2 = Hostility; 3 = Indifference; 4 = Intimidation; 5 = Imposition of behaviour; 6 = Blaming; 7 = Apparent kindness. The values of items 23, 36, 48, and 50 are not shown because they correspond to the items excluded from the CVPPar after the statistical analyses.

As a final result of this analysis, we obtained a scale with 46 items divided into seven factors that showed an adequate and optimum fit. Lastly, the factors were given names, taking into account the common characteristics of the elements of each and following the conceptualisation of Taverniers (2001). Thus, factor 1 is called Devaluation, factor 2 Hostility, factor 3 Indifference, factor 4 Intimidation, factor 5 Imposition of behaviour, factor 6 Blaming and factor 7 Apparent kindness.

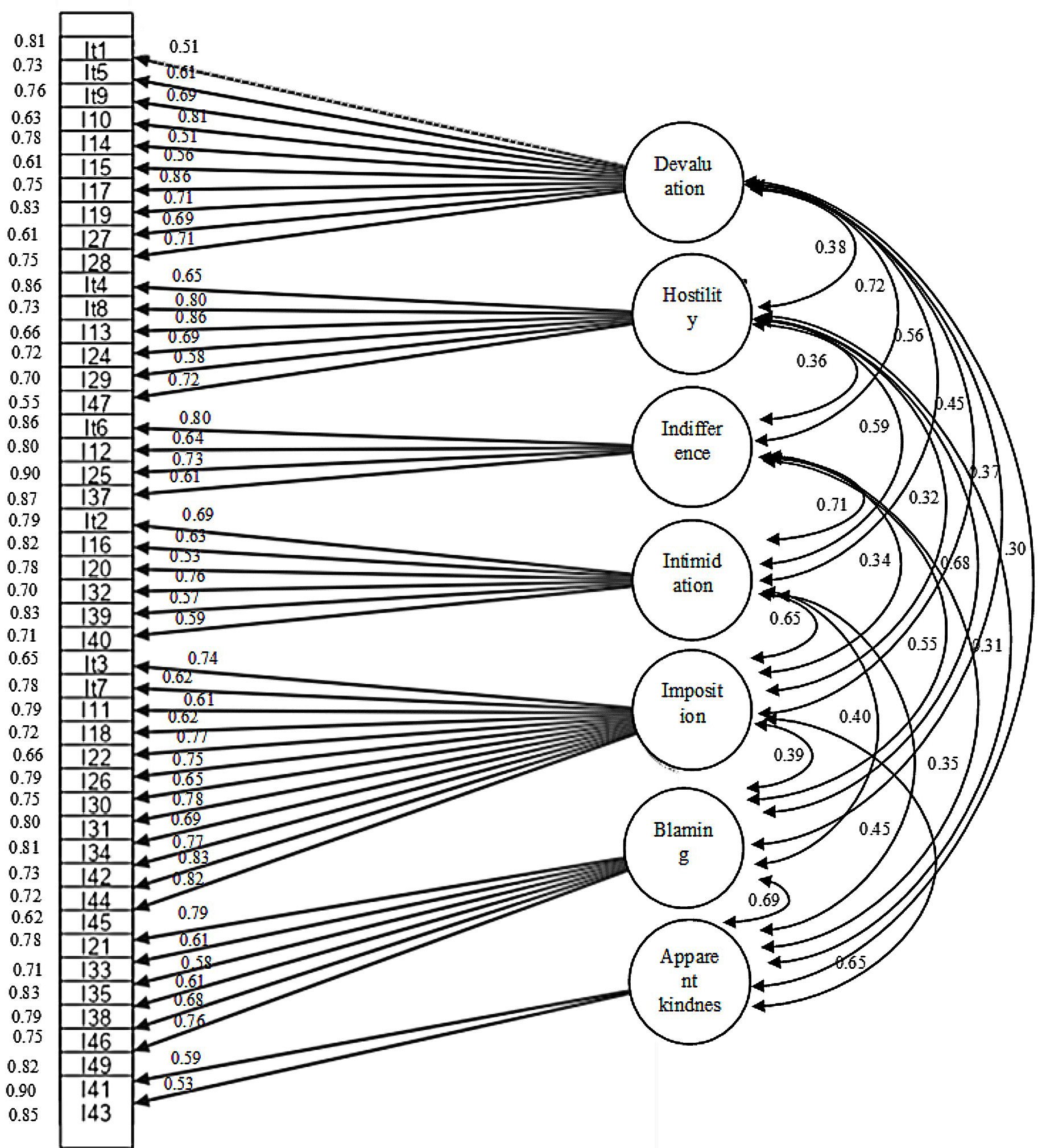

The model obtained from the EFA needs to be confirmed using the CFA. The parameters for the CFA were extracted using the maximum verisimilitude estimation method. On utilising the CFA to check the composition with seven factors, the results obtained told us the following:

The model formulated provides adequate indices with

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Structure of the seven factor model from confirmatory factorial analysis.

We decided to carry out an invariance analysis to check whether the factorial structure of the CVPPar differs depending on the gender of the participant. First of all, it showed that there were no statistically significant differences observed in the configuration invariance (M1) according to gender. Thus, we can conclude from the obtained indices that the structure of the CVPPar is similar for both males and females and we can assume configuration invariance according to gender. Metric invariance (M2) between genders can also be assumed as no statistically significant differences were observed in this respect. As for scalar invariance (M3), the equality restriction is imposed in the intersections and, after comparing the model’s fit with the metric invariance, the results show that it is not statistically significant. In addition, it is evident that the differences in the incremental adjustment indices are below the established criteria. We can therefore state that there is scalar invariance in the groups compared (Table 4). Consequently, the CVPPar can be considered as having a structure that adjusts to the factorial invariance model.

| Model | df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | ||||

| Male | 219.79 | 152 | 0.974 | 0.967 | 0.048 | 0.047 | |||

| Female | 228.12 | 152 | 0.959 | 0.978 | 0.049 | 0.054 | |||

| Configural model | 275.08 | 151 | 0.956 | 0.967 | 0.053 | 0.057 | |||

| Metric Model | 273.64 | 163 | 0.966 | 0.973 | 0.054 | 0.066 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.009 |

| Scalar model | 276.42 | 169 | 0.965 | 0.968 | 0.052 | 0.067 | –0.005 | –0.002 | 0.001 |

Notes: TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, Root

Mean Square Error of Approximation; SRMR, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual;

We used Cronbach’s

It was observed that the elimination of any element from the questionnaire did

not lead to a notable increase in either Cronbach’s

A correlation analysis showed significant associations between the CVPPar scores and other, theoretically related variables. The different CVPPar factors were significantly correlated in a positive form with the measures of physical aggression, psychological abuse, sexual coercion, injuries, somatization, anxiety and depression. The CVPPar factors therefore correlated in a significant and negative way with negotiation. As expected, those of the CVPPar showed stronger factor correlations with such convergent measures as psychological abuse (Table 5).

| CVPPar | ||||||||

| CTS-2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Negotiation | –0.22* | –0.27* | –0.26* | –0.17* | –0.20* | –0.25* | –0.22* | |

| Physical aggression | 0.40* | 0.49* | 0.48* | 0.57* | 0.54* | 0.41* | 0.38* | |

| Psychological abuse | 0.71* | 0.69* | 0.70* | 0.77* | 0.75* | 0.78* | 0.68* | |

| Sexual coercion | 0.43* | 0.37* | 0.44* | 0.51* | 0.58* | 0.54* | 0.49* | |

| Injuries | 0.43* | 0.50* | 0.51* | 0.46* | 0.47* | 0.49* | 0.51* | |

| BSI-18 | ||||||||

| Somatization | 0.35* | 0.31* | 0.37* | 0.32* | 0.36* | 0.29* | 0.30* | |

| Depression | 0.43* | 0.49* | 0.36* | 0.42* | 0.51* | 0.48* | 0.43* | |

| Anxiety | 0.54* | 0.51* | 0.49* | 0.63* | 0.49* | 0.48* | 0.47* | |

Notes: CVPPar, Questionnaire on Psychological Violence in

Intimate Partner Relationships; CTS-2, Revised Conflict Tactics Scales; BSI-18,

Brief Symptom Inventory 18; 1 = Devaluation; 2 = Hostility; 3 = Indifference; 4 =

Intimidation; 5 = Imposition of behaviour; 6 = Blaming; 7 = Apparent

kindness. *p

In accordance with the objective of the study proposed in this paper and due to the lack of a tool to study psychological violence in an integral way, we addressed the creation of a valid and reliable research instrument to study the said phenomenon and its manifestations in intimate partner relationships. The Questionnaire on Psychological Violence in Intimate Partner Relationships (“Cuestionario de violencia psicológica en la pareja”, CVPPar) is thus presented as a tool to provide an in depth evaluation of psychological violence and its manifestations in intimate partner relationships, from the most overt to the most subtle levels of expression (Appendix Table 6).

As indicated in the results section, the instrument possesses psychometric properties which make it a relevant indicator of psychological violence in intimate partner relationships, independently of the gender of the perpetrator. Therefore, and unlike the majority of studies concerning psychological violence in intimate partner relationships, it is not necessarily directed at evaluating the violence of men against women, as a variant of gender based violence (Ahmed et al, 2024).

In this sense, its perpetration can be related to any member of a romantic couple, with profound and lasting consequences that affect the victim’s wellbeing. In this respect, prior research works have established that psychological violence has a serious impact on the victim’s health. The development of PTSD is in fact one of the main characteristics of the psychopathological profile, and added to that are other clinical symptoms such as depression or anxiety, as well as suicidal tendencies and a profound lack of social adaptation and interference in daily functioning (Esteves-Pereira et al, 2020). Apart from the evident repercussions this type of violence can have, this phenomenon is insidious, subtle and difficult to detect. As did previous works of research, this fact underlines the critical need for an effective, reliable and valid method with which to identify and accurately and systematically evaluate this form of violence in the male and/or female population (Almendros et al, 2009; Arabi, 2023).

Thus, starting with the exhaustive categorization of the manifestations of psychological violence carried out by Taverniers (2001), and based on the theoretical considerations, the CVPPar is clearly an instrument that is responsive to a wide range of violent behaviour and experiences that occur within intimate partner relationships. Examining the information provided by this instrument concerning such dimensions of psychological violence in intimate partner relationships as devaluation, hostility, indifference, intimidation, imposition of behaviour, blaming and apparent kindness, facilitates the goal of eventually eradicating this phenomenon which gradually and progressively degrades and negates the victim (Tourné et al, 2024).

Unlike other studies that measure intimate partner violence in general, contemplating only a limited number of violent behaviour types, this research stresses the need to explore the most difficult manifestations to detect precisely because of their inherent danger (Heise et al, 2019). Such is the case of trivialization (which includes devaluation), blaming (including gaslighting, denial) and abusive insistence and deflecting, as ways of imposing behavioural restrictions and manipulating reality as though such manipulation were an act of apparent kindness.

Such instruments as the widely used CTS-2 of Straus et al (1996) provides a

robust framework for evaluating violence within couples, with the global scale

achieving a Cronbach’s

Furthermore, from this perspective, having valid and reliable psychometric instruments is essential as a source of quantitative data to understand the differences, patterns and correlations of psychological violence according to the different variables. In this respect, significant differences have been found in devaluation, intimidation and imposition of behaviour according to gender, the scores being greater in women. In addition, concerning age, we have shown that the older age group (21 to 23 years) has higher scores in devaluation, imposition of behaviour and blaming. In this sense, different studies indicate that women suffer intimate partner violence to a greater extent, as well as coactive interaction patterns at a young age (Caldwell et al, 2012; Hokoda et al, 2012).

Among the study’s limitations, we must mention the low reliability presented by the Apparent kindness factor. This dimension is represented by smaller number of items, the number being theoretically fundamental in order to show the manipulation of reality contemplated by Taverniers (2001) in his categorization. Simulating love and interest in order to justify violent conduct is an apparent act of kindness which hides the manipulation of reality (Martínez et al, 2024). Along these lines, given the theoretical relevance and clinical implications, the need to include a factor with these characteristics is justified. Furthermore, the selection procedure for the sample limits the representative nature of the said selection, as well as the generalisation of the results obtained. Therefore, in future studies, it would be interesting to use a probabilistic sampling. On the other hand, we would not have a measure completely equivalent to the CVPPar, taking into account the fact that we would be analysing the validity by means of variables that are theoretically related.

The present investigation aims to design and validate an instrument for measuring psychological violence in relationships and to determine its psychometric properties. To conclude, we must point out that the Questionnaire on Psychological Violence in Intimate Partner Relationships (“Cuestionario de violencia psicológica en la pareja”, CVPPar) is the product of a complex and prolonged process of design and validation, in which the applied techniques offer a psychometric guarantee of validity and reliability for its use by the scientific community. Similarly, this questionnaire not only constitutes a complete tool for acquiring a global vision of psychological violence and its manifestations in intimate partner relationships, but it is also a resource with an important value for application in clinical psychology, propitiating the detection of this problem for prevention and/or treatment of the victims. It will allow concrete measures to be taken aimed at the manifestations of psychological violence suffered by each and every victim, thus achieving an adequate adjustment to the particular circumstances surrounding each individual situation.

The authors confirm that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conceptualization, LP-D, MB-A and JMM-M; methodology, LP-D, MB-A and JMM-M; software, LP-D, MB-A and JMM-M; formal analysis, LP-D, MB-A and JMM-M; investigation, LP-D, MB-A and JMM-M; writing, LP-D, MB-A, and JMM-M; supervision, MB-A and JMM-M. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All the procedures carried out complied with the directives concerning their adaptation to the International Test Commission (ITC; Hambleton, 2001), as well as to the ethical standards of the University of Extremadura (Ref.: 92/2020) and to the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later modifications or comparable ethical standards. All subjects gave informed consent for inclusion before participating in the study.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See Table 6.

| Below, we present a series of statements concerning your intimate partner relationship. Read each statement and mark the number that best coincides your degree of agreement or disagreement, using the following scale: 0. Never 1. Rarely 2. Sometimes 3. Frequently 4. Always | |

| 1. My partner publicly makes fun of me and then says it was a joke. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 2. My partner constantly corrects me in everything I do. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 3. My partner accuses me of preferring my hobbies to him/her. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 4. My partner threatens me with harming him/herself if I leave him/her. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 5. My partner rejects my displays of affection. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 6. My partner is not willing to adapt to my needs and expectations. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 7. My partner believes that she/he has the right to force me to do things. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 8. My partner recalls things from the past in order to hurt me. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 9. My partner tells me I don’t know what I am talking about. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 10. My partner tells me I get angry over nothing. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 11. My partner doesn’t want me to do activities that can promote me in any sphere of my life. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 12. My partner doesn’t take my feelings into account. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 13. My partner usually reproaches me for not acting as I should. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 14. My partner makes jokes about my complexes. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 15. My partner justifies her/his attacks by saying I am too sensitive. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 16. My partner usually comes too close to me when reproaching me for something. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 17. My partner gets angry if I don’t agree with him/her. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 18. My partner tries to stop me seeing my family. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 19. My partner shows disdain towards me when we argue. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 20. My partner has broken my personal objects more than once during arguments. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 21. My partner denies having said things to me that she/he did say. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 22. My partner reads the messages in my mobile phone. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 23. My partner threatens me with ending the relationship. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 24. My partner insults me. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 25. My partner takes for granted that I want to do the same things as she/he does. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 26. My partner complains if I don’t obey his/her whims. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 27. My partner gets very angry if I disagree with his/her opinions. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 28. My partner always compares me to her/his friends’ partners. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 29. My partner shames me in public. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 30. When my partner doesn’t want to talk about something, he/she quickly interrupts me. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 31. My partner doesn’t like me to go out with my friends. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 32. My partner criticises and judges every decision I take. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 33. My partner accuses me of constantly imagining things that do not happen. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 34. My partner constantly interrogates me if I say hello to someone he/she doesn’t know. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 35. My partner denies insulting me when she/he gets angry. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 36. My partner accuses me of being the cause of all her/his problems. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 37. My partner decides on his/her own important matters that affect us both. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 38. My partner accuses me of inventing the fact that he/she is hurting me. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 39. My partner physically pushes me around when angry with me. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 40. When my partner gets angry, he/she punches the table, doors, etc. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 41. My partner says she/he insults me so I can learn how to do things well. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 42. Mi partner cuts off our conversations whenever she/he feels like it. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 43. My partner says he/she doesn’t like me going places without him/her because he/she is trying to protect me. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 44. My partner is very persistent, until he/she gets what he/she wants of me. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 45. My partner insists repeatedly in his/her opinions until I agree. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 46. My partner accuses me of not being “normal like other men/women”. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.