1 Radiology Center, Bach Mai Hospital, 100000 Hanoi, Vietnam

2 Vietnam National Heart Institue, Bach Mai Hospital, 100000 Hanoi, Vietnam

3 Department of Medical Imaging and Intervention, Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, 333 Taoyuan City, Taiwan

Abstract

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a primary cardiac disorder characterized by myocardial hypertrophy without increased afterload. This study set out to describe the cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging characteristics of HCM and to evaluate correlations of selected CMR parameters with echocardiography.

This cross-sectional study enrolled 46 patients diagnosed at the Vietnam Heart Institute with HCM and underwent CMR at the Radiology Center, Bach Mai Hospital, from July 2021 to September 2022.

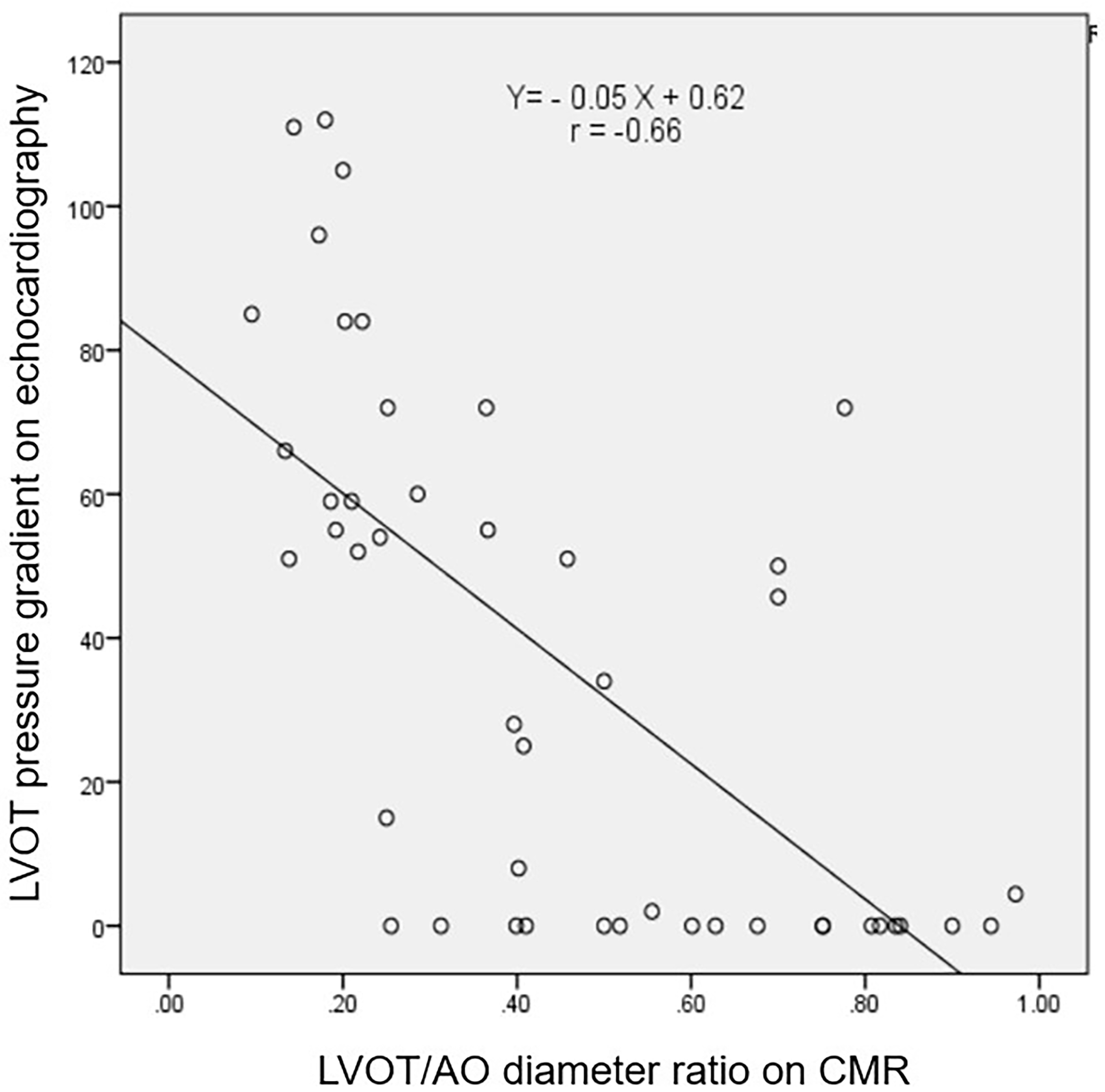

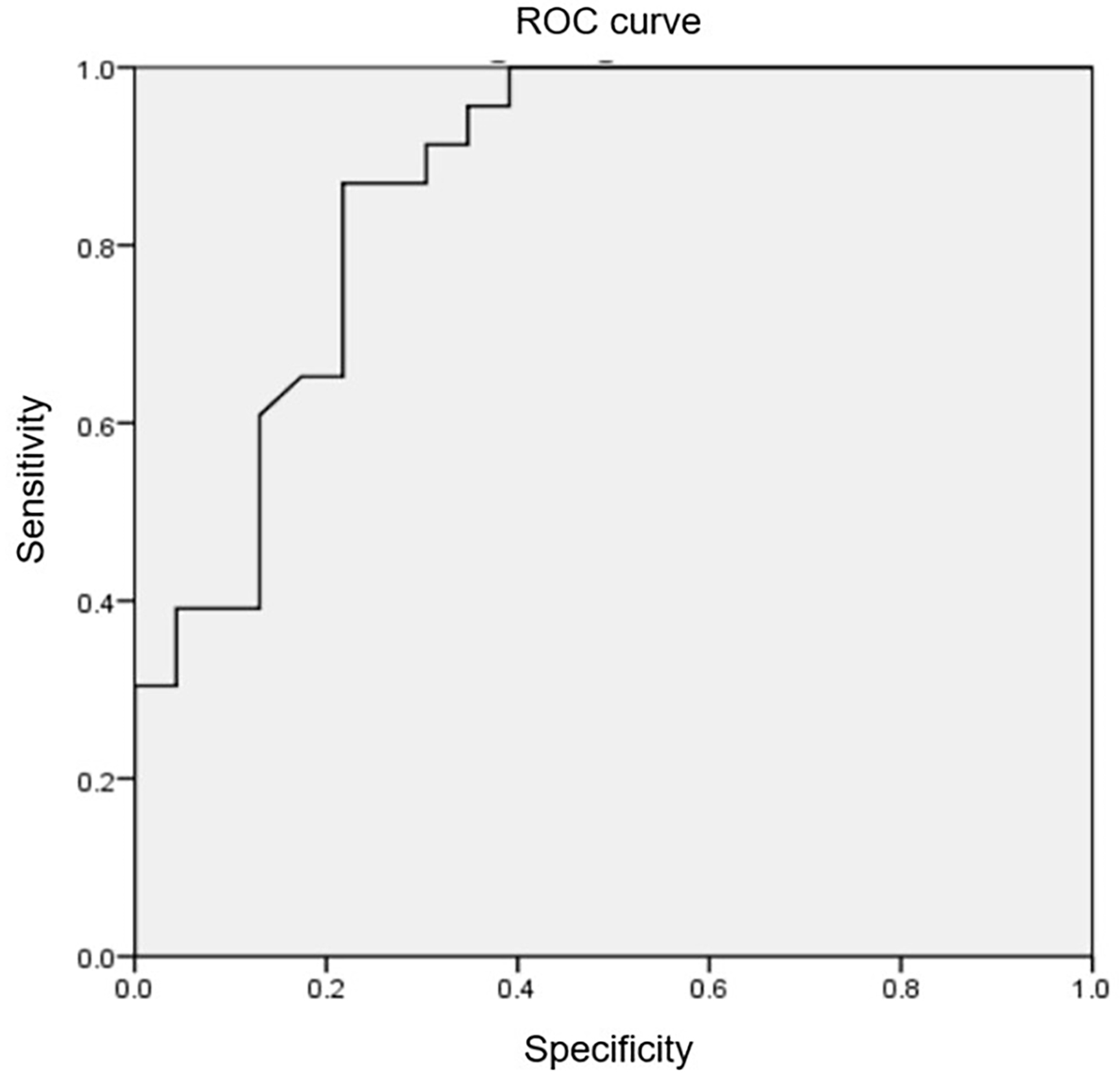

A left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT)/aortic valve (AO) diameter ratio of ≥0.38 on CMR was consistent with an LVOT pressure gradient (PG) of <30 mmHg on echocardiography. The LVOT diameter and the LVOT/AO diameter ratio differed significantly between obstructive and non-obstructive HCM. The predominant phenotypes were diffuse asymmetric HCM (32.6%) and septal HCM (37%), followed by apical HCM (6.5%). Most late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) lesions were observed in the mid-wall of the hypertrophic segments. The mean LGE mass was significantly higher in the obstructive group than in the non-obstructive HCM group (p < 0.05). A strong negative correlation (r = –0.66) was found between the LVOT/AO diameter ratio on the CMR and the LVOT PG via echocardiography. Moreover, echocardiography detected morphologic risk factors for sudden cardiac death (SCD) in 80.4% of patients, whereas the corresponding proportion detected by CMR was 91.3%. Patients with systolic anterior motion (SAM) had a risk for a LVOT/AO diameter ratio <0.38, which was 5.7 times the risk observed in their counterparts without SAM.

The LVOT/AO diameter ratio detected by CMR is a precise index for classifying hemodynamic HCM groups. CMR was better than echocardiography for SCD risk stratification.

Keywords

- hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- magnetic resonance imaging

- echocardiography

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a primary cardiac disorder characterized by myocardial hypertrophy in the absence of any detectable increase in afterload (i.e., systemic hypertension or aortic stenosis). Still considered a disease burden worldwide, HCM has an estimated population prevalence of 0.2% (1/500) and is among the most common causes of sudden cardiac death (SCD), especially in patients under 35 years of age [1]. Therefore, the early and accurate diagnosis of HCM is crucial in the direction of care, timely treatment, and preventing complications.

HCM is divided into obstructive and non-obstructive groups based on peak gradient at the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) or mid-left ventricular cavity. LVOT obstruction is defined as a gradient greater than 30 mmHg that can lead to adverse outcomes. Usually, echocardiography is used to assess LVOT obstruction; however, echocardiography may not always be sufficient to diagnose HCM definitively, particularly in patients whose ultrasound window is limited and whose signs of hypertrophy are unclear [2]. In recent years, the emergence of cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging has overcome these echocardiography limitations and presents many obvious advantages, such as visualization of the myocardium and high reproducibility. CMR is now considered the reference standard for quantifying left ventricular (LV) volume, mass, wall thickness, function, and phenotypic classification. CMR has been recommended to aid echocardiography in definitive diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment of HCM [3]. However, the correlation between the LVOT/aortic valve (AO) diameter ratio on CMR imaging and the LVOT pressure gradient (PG) on echocardiography has yet to be assessed adequately. In addition, HCM phenotypes vary among Europeans and Asians [4] and different countries within Asia [5, 6]. Therefore, we conducted this study to provide additional information on the imaging characteristics of HCM in Asians and evaluate the correlations of selected CMR parameters with echocardiography.

Following the initial selection of 52 patients, 6 patients were excluded due to the non-diagnostic quality of CMR images. Finally, 46 patients diagnosed at the Vietnam National Heart Institute with HCM and underwent CMR at the Radiology Center, Bach Mai Hospital, from July 2021 to September 2022 were included.

• The patient was diagnosed with HCM according to the European Society of Cardiology 2014 guidelines.

• The patient provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

• The patient had a CMR contraindication (metal foreign body in the orbit, skull, heart, etc., or an implantable medical device such as a hearing aid or pacemaker).

• The patient had a medical, surgical, metabolic, or occupational condition that could be responsible for myocardial hypertrophy, such as hypertension or amyloidosis.

• The patient was allergic to contrast agents or had severe renal failure.

• The magnetic resonance images obtained were of non-diagnostic quality.

• The patient had claustrophobia or could not cooperate during CMR imaging.

Images were acquired using a 3T magnetic resonance imaging machine (SIGNA Architect: GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL, USA). Heart MR images were obtained using a 30-channel adaptive image receive (AIR) anterior array coil and a 40-channel posterior array coil. Multiple-plane localizers were taken first, including axial, coronal, sagittal, two-chamber, three-chamber, four-chamber, short-axis, and LVOT views. Two-chamber, four-chamber, short-axis cine sequences (8–10 slices) from base to apex were obtained next. Then, 3-chamber and LVOT cine sequences were used to assess systolic anterior motion (SAM). One midventricular short-axis view for native T1 was acquired using modified look–locker inversion recovery, with 11 images and 17 heartbeats 3-(3)-3-(3)-5 balanced steady-state free precession sequences. The same short-axis view for T2 mapping was obtained using a T2 steady-state free precession sequence. Subsequently, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) images with one slice on two-chamber and four-chamber views and eight slices on a short-axis view from base to apex were acquired 10 min after intravenous administration of gadolinium-based contrast (Dotarem: Guerbet, Villepinte, France) at a dose of 0.2 mmol/kg and a rate of 2–3 mL/s, followed by administration of 20–25 mL saline. Finally, postcontrast modified look–locker inversion recovery T1 mapping was obtained on the same short-axis slice previously used for the precontrast T1 mapping. Two radiologists with over five years of experience analyzed the data using MR Workspace (Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) with CVi42 software (Circle Cardiovascular Imaging, Calgary, AB, Canada). LV mass, ejection fraction (EF), LV end-systolic volume, end-diastolic volume, wall thickness, and LVOT diameter were calculated. Consensus was obtained following a discussion of any discrepancies between the two radiologists.

Data are presented as the mean

The 46 study patients comprised 27 men (58.7%) and 19 women (41.3%). The mean

age in the cohort was 51.2

Concerning clinical characteristics, 15 patients (32.5%) had a family history of HCM, 14 (30.4%) had a family history of SCD, 1 (2.2%) had a family history of implantable cardioverter–defibrillator, 34 (73.9%) had dyspnea, and 36 (78.3%) had chest pain. The echocardiogram features and phenotypic findings for HCM are shown in Supplementary Tables 1,2, respectively.

HCM was classified as obstructive or non-obstructive on CMR based on comparing the LVOT/AO diameter ratio with the LVOT PG on echocardiography, using a receiver operating characteristic curve to determine the cut-off point (Figs. 1,2). Of the 46 patients, 21 (45.7%) had obstructive HCM based on the LVOT/AO diameter ratio.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Correlation between the LVOT PG on echocardiograph and the LVOT/AO diameter ratio on cardiac magnetic resonance image. The figure shows a strong negative correlation (r = –0.66) between the LVOT PG on echocardiography and the LVOT/AO diameter ratio on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; AO, aortic; PG, pressure gradient; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The receiver operating characteristic curve and the cut-off

point of LVOT/AO diameter ratio. Utilizing the receiver operating characteristic

curve, the LVOT/AO diameter ratio on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was

identified as 0.38, with an area under the curve of 0.87, a sensitivity of 87%,

and a specificity of 78.3%, allowing for the detection of an LVOT PG

The assessment of LVOT/AO diameter ratio on the 3-chamber steady-state free precession CMR image, cine 4-chamber view obtained at end-diastolic phase, the severe LVOT obstruction with positive SAM on cine 3-chamber and LVOT views, and late gadolinium enhancement with a transmural and mid-wall pattern are shown on Supplementary Figs. 1–4, respectively.

Table 1 compares the LV parameters on the CMR between the obstructive and

non-obstructive HCM groups. No significant differences were observed

between the groups (p

| Parameters | Obstructive HCM (n = 21, |

Non-obstructive HCM (n = 25, |

p-value |

| LV EDV (mL) | 110.7 |

117.3 |

0.46 |

| LV ESV (mL) | 34.2 |

42.95 |

0.117 |

| LV EF (%) | 69.03 |

64.3 |

0.119 |

| LV mass (g) | 165.3 |

182.3 |

0.332 |

| Maximum wall thickness (mm) | 22.4 |

22.8 |

0.805 |

| LVAi (mL/m2) | 53.4 |

41.2 |

0.09 |

| LVOT diameter (mm) | 4.5 |

13.3 |

0.00 |

| LVOT/AO diameter ratio | 0.22 |

0.65 |

0.00 |

| Native T1 (ms) | 1259 |

1198 |

0.014 |

LV, left ventricular; EDV, end-diastolic volume; ESV, end-systolic volume; EF, ejection fraction; LAVi, left atrial volume index; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; AO, aortic; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Table 2 presents the HCM phenotypes for the CMR. Of the 46 patients, 3 (6.5%) had bilateral ventricle hypertrophy, and 4 (8.7%) had concentric HCM. Septal HCM accounted for the highest proportion of cases (37%, 17/46), followed by diffuse symmetric HCM (32.6%, 15/46). Notably, the proportion of the septal phenotype in the two groups was significantly different (p = 0.009).

| HCM phenotypes on the cardiac magnetic resonance imaging | Obstructive (n = 21) | Non-obstructive (n = 25) | Total (n = 46) | p-value | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| LV (n = 43) | Asymmetric HCM (n = 39) | Diffuse asymmetric HCM | 5 | 23.8 | 10 | 40.0 | 15 | 32.6 | 0.24 |

| Septal HCM | 12 | 57.1 | 5 | 20.0 | 17 | 37.0 | 0.009 | ||

| Mid septal HCM | 0 | 0 | 3 | 12.0 | 3 | 6.5 | 0.24 | ||

| Apical septal HCM | 1 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.2 | 0.5 | ||

| Apical HCM | 2 | 9.5 | 1 | 4.0 | 3 | 6.5 | 0.6 | ||

| Concentric HCM | 0 | 0 | 4 | 16.0 | 4 | 8.7 | 0.1 | ||

| Both left and right ventricles | 1 | 4.8 | 2 | 8.0 | 3 | 6.5 | 0.7 | ||

HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LV, left ventricular.

LGE was observed via CMR imaging for 23 patients (Table 3). The mean LGE mass in

the obstructive group was higher than in the non-obstructive group (20.6

| LGE (n = 23) | Obstructive (n = 9) | Non-obstructive (n = 14) | Total (n = 23) | p-value | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Hypertrophic segment | 8 | 88.9 | 12 | 85.7 | 20 | 87.0 | 0.6 | |

| Distribution | Subendocardial | 2 | 22.2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8.7 | 0.08 |

| Epicardial | 2 | 22.2 | 4 | 28.6 | 6 | 26.1 | 0.4 | |

| Mid-wall | 6 | 66.7 | 10 | 71.4 | 16 | 69.6 | 0.5 | |

| Transmural | 1 | 11.1 | 4 | 28.6 | 5 | 21.7 | 0.3 | |

| Patterns | Nodule | 3 | 33.3 | 4 | 28.6 | 7 | 30.4 | 0.8 |

| Patchy | 7 | 77.8 | 12 | 85.7 | 19 | 82.6 | 0.7 | |

| Linear | 5 | 55.6 | 4 | 28.6 | 9 | 39.1 | 0.2 | |

| LGE mass (g/m2) | 20.6 |

10.8 |

14.6 |

0.04 | ||||

LGE, late gadolinium enhancement.

Table 4 shows that 52.2% of patients had SAM, and 10.9% had ventricular aneurysms. The SAM was significantly more common in obstructive HCM than in non-obstructive HCM (90.5% vs. 20.0%, p = 0.00).

| Obstructive (n = 21) | Non-obstructive (n = 25) | Total (n = 46) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Systolic anterior motion | 19 | 90.5 | 5 | 20.0 | 24 | 52.2 | 0.00 |

| Ventricular aneurysm | 1 | 4.0 | 4 | 19.0 | 5 | 10.9 | 0.1 |

Table 5 indicates that CMR was better for evaluating maximum wall thickness

| Echocardiography (n, %) | CMR (n, %) | Kappa value | |

| Wall thickness |

3 (6.5) | 6 (13.0) | 0.3 |

| Ventricular aneurysm | - | 5 (10.9) | - |

| LGE | - | 23 (50.0) | - |

| EF |

2 (4.3) | 4 (8.7) | 0.3 |

| SCD risk | 37 (80.4) | 42 (91.3) | 0.2 |

| SAM | 25 (54.3) | 24 (52.2) | 0.6 |

HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; EF, ejection fraction; SCD, sudden cardiac death; SAM, systolic anterior motion.

Supplementary Table 3 showed that patients with SAM exhibited a 5.7

times higher risk of having an LVOT/AO diameter ratio

In this cohort, the 46 patients diagnosed with HCM had an average age of 51.2

In this study, patients experienced syncope, dyspnea, and chest pain as their most common symptoms. The prevalence of dyspnea, at 73.9% (approaching New York Heart Association class II), was comparable to findings reported by Alashi et al. [10]. However, the rates of chest pain and syncope in the current study (78.3% and 23.9%, respectively) were higher than the 19% and 12% reported in the study by Alashi et al. [10], although the variations in age distribution and a higher proportion of patients with heart failure in the current study might have influenced these differences.

Our study revealed a strong negative correlation between LVOT PG on

echocardiography and the LVOT/AO diameter ratio on CMR (r = –0.66). Using a

receiver operating characteristic curve, we established that an LVOT/AO diameter

ratio of 0.38 measured by CMR, with an area under the curve of 0.87, a

sensitivity of 87%, and a specificity of 78.3%, allowed for the detection of an

LVOT PG

The mean maximum LV wall thickness observed in this study was similar to the

previously reported value of 22

An outstanding advantage of CMR imaging compared with echocardiography is the detection of myocardial fibrosis by LGE, not only in hypertrophic segments but also in non-hypertrophic areas. LGE mass plays a role in disease progression and prognosis and is possibly the cause of ventricular arrhythmias. Half of the study patients had LGE, a proportion lower than that reported by Thao et al. [13] (88.9%), likely because of differences in sample size, study location, time, and disease stage. Some studies have revealed that the rate of LGE varies and can be as high as 60%–70% in adults and 46% in children [13, 15]. These results are similar to those reported by Mentias et al. [16]. The distribution of LGE mainly in the mid-wall of the hypertrophic segments with plaque pattern in the current study accords with findings in a previous series [17]. These features are consistent with the characteristics of nonischemic cardiomyopathy and do not fall into coronary artery territory. The LGE measurement indicated the amount of fibrous tissue, denoting disease progression and prognosis. In this study, the mean LGE mass in the obstructive HCM group was twice that in the non-obstructive HCM group. In addition, native T1 values could reflect histologic remodeling of the myocardium and become widely used in clinical practice [18]. In this study, the native T1 value was higher in the obstructive HCM group than in the non-obstructive HCM group, denoting more advanced myocardial tissue remodeling in the obstructive group.

In cardiovascular disease, echocardiography is a non-invasive, widely available,

and valuable diagnostic tool, whereas CMR is a high-cost test that can complement

and address the limitations of echocardiography. A LV wall thickness

The 2020 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline

outlines seven risk factors for HCM SCD risk stratification, including a family

history of sudden death from HCM, wall thickness

This study further identified a negative correlation between the LVOT/AO

diameter ratio according to CMR and the LVOT PG according to echocardiography,

consistent with previous reports [11, 23]. SAM of the mitral valve narrows the

LVOT, reducing the LV ejection volume. As a compensatory mechanism, the heart

contracts rapidly and forcefully, elevating the velocity through the LVOT and

resulting in increased LVOT PG. In this study, without examining LVOT PG

directly, we found that those with SAM had a 5.7 times greater likelihood of

having an LVOT/AO diameter ratio

This study has certain limitations. First, it was conducted at a single center with a relatively small sample size. Second, genetic testing was only performed on some patients. Finally, the follow-up duration was short; only seven patients underwent myomectomy. Subsequently, further research is needed to address these issues.

The LVOT/AO diameter ratio measured by CMR represents a precise index for categorizing hemodynamic HCM groups. The findings of this study suggest that CMR outperforms echocardiography in the stratification of SCD risk.

The datasets analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; LV, left ventricular; LVOT, LV outflow tract; AO, aortic valve; PG, pressure gradient; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; SCD, sudden cardiac death; SAM, systolic anterior motion.

VDL and PMH, YLW designed the research study. PBN, VTKT, NNT and NKV performed the research. HTVH, NTH and LTTL analyzed the data. PBN, NNT and NTH wrote the manuscript. NNT and YLW revised the manuscript and gave final approval of the version. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript and approved the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam approval for this study (ID # 2338), and the board decided to waive the requirement for obtaining informed consent, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1989) by the World Medical Association.

We would like to thank all cardiologists from Vietnam National Heart Institute for their support.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Yung Liang Wan is serving as Guest Editor of this journal. We declare that Yung Liang Wan had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Sophie Mavrogeni and John Lynn Jefferies.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.rcm2509341.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.