1 Department of Anesthesia, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Yunnan University of Chinese Medicine, Kunming Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 650500 Kunming, Yunnan, China

2 Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Baoying People’s Hospital, 225800 Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China

3 Department of Nursing, Haikou Orthopedic and Diabetes Hospital of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, 570100 Haikou, Hainan, China

4 College of Nursing, Yunnan University of Chinese Medicine, 650500 Kunming, Yunnan, China

5 Department of Clinical Medicine, Baoying People’s Hospital, 225800 Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Recently, there has been a surge in virtual reality (VR)-based training for upper limb (UL) rehabilitation, which has yielded mixed results. Therefore, we aimed to explore the effects of conventional therapy combined with VR-based training on UL dysfunction during post-stroke rehabilitation.

Studies published in English before May 2023 were retrieved from PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library. We also included randomized controlled trials that compared the use of conventional therapy and VR-based training with conventional therapy alone in post-stroke rehabilitation. The meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager Software (version 5.3; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; Copenhagen, Denmark) and Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp, LLC, College Station, TX, USA). Univariate and multivariate meta-regression analyses were performed to investigate the effects of stroke duration, VR characteristics, and type of conventional therapy on VR-based training.

In total, 27 randomized controlled trials were included, which enrolled 1354 patients. Our results showed that conventional therapy plus VR-based training is better than conventional therapy alone in UL motor impairment recovery measured using Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.32, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.07–0.57, Z = 2.52, p = 0.01). Meta-regression showed that stroke duration had independent effects on Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity scores of VR-based training in rehabilitation (p = 0.041). Furthermore, in subgroup analysis based on stroke duration, stroke duration >6 months was statistically significant (SMD = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.01–0.39, Z = 2.06, p = 0.04). No relevant publication bias (p = 0.1303), and no significant difference in activity limitation assessed using the Box-Block Test (mean difference [MD] = 2.79, 95% CI: –0.63–6.20, Z = 1.60, p = 0.11) was observed. Regarding the functional independence measured using the Functional Independence Measure scale, studies presented no significant difference between the experimental and control groups (MD = 1.15, 95% CI: –1.84–4.14, Z = 0.76, p = 0.45).

Conventional therapy plus VR-based training is superior to conventional therapy alone in promoting the recovery of UL motor function after stroke. Therefore, VR-based training may be a potential option for improving UL motor function. The study was registered on PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/), registration number: CRD42023472709.

Keywords

- meta-analysis

- meta-regression

- post-stroke rehabilitation

- upper limb dysfunction

- virtual reality

Stroke is a prevalent condition that significantly threatens human health and is

the second leading cause of disability worldwide [1, 2]. Annually, approximately

101 million individuals live with post-stroke syndrome, and one in four people

experiences stroke during their lifetime, representing a 50% increase over the

past 17 years [3]. The estimated global economic burden of stroke exceeds

Stroke mortality rates have remained stable over the past decade; however, its prevalence has notably increased [6]. This upward trajectory has led to substantial enduring disabilities in adults [7], characterized by profound brain tissue damage and numerous neurological deficits, of which limb dysfunction is the most prevalent and severe. Furthermore, upper limb (UL) function recovery is particularly complex, with relatively poor outcomes, significantly impacting the patients’ independence in daily activities, severely diminishing their quality of life, and thus imposing a substantial burden on families and society. Therefore, enhancing the UL functional status and optimizing functional independence in post-stroke individuals is imperative.

Contemporary clinical interventions for UL rehabilitation focus on fostering neuroplasticity post-brain injury [8, 9]. Conventional therapies, such as occupational and physical treatments, help ameliorate UL motor deficits post-brain injury [10]. However, these methods are time-consuming and monotonous and often rely on the expertise of medical personnel. This has initiated the development of novel and efficacious therapeutic approaches, such as virtual reality (VR)-based training [11].

VR is an innovative intervention in rehabilitation nursing that harnesses integrated technologies to construct realistic three-dimensional environments by amalgamating visual, auditory, and tactile components. Users immerse themselves in the simulated scenarios, interact with their environment, and receive real-time feedback, thereby fostering immersive experiences for stroke rehabilitation. VR interventions featuring repetitive activities and tasks facilitate limb function recovery post-stroke [12]. Their engaging and motivating nature provides entertainment and immediate feedback on motor performance. This fosters increased patient engagement, resulting in high patient compliance and cost-effectiveness.

The research team led by Laver et al. [11] assessed 22 studies that were either randomized or quasi-randomized in a controlled format, and they found no substantial proof to suggest that VR outperforms traditional treatments when it comes to enhancing arm functionality. However, a subsequent review by Zhang et al. [13] reached a different conclusion, stating that VR-based training effectively enhanced UL motor function in patients with stroke. Recently, there has been a surge in VR-based training for UL rehabilitation, which has yielded mixed results. Consequently, we implemented a meta-analysis incorporating a pooled analysis and a multifactorial design, focusing on various effect modifiers and meta-regression.

This meta-analysis synthesis sought to assess the impact of VR-based exercises on UL impairments in post-stroke individuals.

The current investigation adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement and its accompanying checklist (see Supplementary Tables 1,2) and was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023472709).

We thoroughly searched PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library from their inception to May 9, 2023. The search terms included (1) patients (cerebrovascular disorders, stroke, cerebral, or hemorrhage) and (2) interventions (virtual reality exposure therapy, virtual, virtuality, or VR).

Studies were included if they were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published

in English. These trials assigned participants to a VR group that received

VR-based training and conventional therapy or a control group (CG) that received

only conventional therapy. The participants were adults (aged

We selected the following primary outcomes: (1) The Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity (FMUE) measure was proposed to evaluate impairments in UL motor function [14]. It comprises 33 items with a total score of 66 points (range: 0–66); the lower the score, the more severe the motor dysfunction. (2) The Box-Block Test (BBT) is used to measure UL activity limitation and can be judged by the number of blocks the affected UL can grasp and release in 1 min. Healthy and affected hands were scored, with higher scores indicating better hand dexterity. The Functional Independence Measure scale (FIM) was used as a secondary outcome measure to assess functional independence. The FIM is a comprehensive 18-item measurement tool that explores the physical, mental, and interpersonal aspects that reflect patients’ daily functions [13]. It has a total score of 126, with higher scores indicating better functional independence in life activities in patients with stroke.

Research articles were omitted when they fulfilled these conditions: (1) the intervention focused on lower extremity rehabilitation. (2) No information on the outcomes of interest. (3) Review articles, case reports, editorials, or abstracts. (4) Inaccurately extractable or missing data. (5) For identical studies that were published more than once, the one providing the fullest dataset was chosen.

Two independent authors initially assessed the studies for potential inclusion. The screening process involved reviewing the titles and abstracts identified through the search and thoroughly examining the full texts based on the predefined inclusion criteria. In cases of disagreement regarding the extracted data, a consensus was reached through discussion or consultation with a third author.

In total, an initial count of 3115 references was pinpointed. After removing duplicates, a total of 2327 papers were assessed for qualification, with 308 research papers advancing to the comprehensive full-text examination subsequent to evaluating their titles and abstracts. However, 27 studies were included after reviewing the full texts [8, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40]. Fig. 1 shows the flowchart of the search and screening.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the search and screening. RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

The Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool was used to assess the risk of bias in the randomized controlled study [41]. We conducted an assessment of the potential bias risk present in each qualifying article, examining eight distinct domains where bias might occur: (i) the creation of a random sequence for participant selection, (ii) the secrecy of allocation assignment, (iii) the masking of participants and staff, (iv) the masking involved in outcome evaluation, (v) the completeness of the outcome data, (vi) the reporting bias, and (vii) additional sources of bias. Two researchers separately reviewed the pertinent articles, and any discrepancies were settled through agreement with the input of a third researcher.

Two researchers systematically annotated the features of the studies under analysis, employing a uniform data abstraction template. In cases of discord, a third researcher’s input was sought to achieve consensus. The information gathered encompassed aspects such as first author, the year of publication, country, patient characteristics (stroke duration, sample size, age, and proportion of males), intervention characteristics (VR session duration, training frequency, and period), comparison characteristics (conventional therapy), outcome measures, and critical elements of the risk of bias evaluation.

Notably, all analyses were conducted using the Review Manager Software (version 5.3; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; Copenhagen, Denmark) and Stata/MP 17.0 software (Stata Corp, LLC, College Station, TX, USA). The outcomes included in the analysis were continuous data. Pooled results were estimated by calculating the mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The I2 statistic was used to assess the heterogeneity between trials. Random-effect models were used to evaluate the pooled treatment effect and minimize the impact of heterogeneity across the studies.

Meta-regression analysis was performed using Stata/MP 17.0 software (Stata Corp,

LLC, College Station, TX, USA) to explore the sources of heterogeneity, and

subgroup analysis was performed based on the sources of heterogeneity [42].

Additionally, sensitivity analyses were also conducted to evaluate the robustness

of the summary estimates and detect whether any individual study accounted for a

large proportion of heterogeneity [43]. For a graphical depiction of the combined

impact, forest plots were created, while funnel diagrams and Begg’s method were

used to ascertain possible publication bias [44]. Notably, all statistical

evaluations were two-sided, with a threshold for statistical relevance

established at a p-value

The 27 RCTs comprised 1354 patients with post-stroke UL dysfunction. Notably, 760 and 594 patients were assigned to the experimental group (EG) and the CG, respectively. In the EG, participants received VR-based training and conventional therapy. However, those in the CG underwent only conventional therapy, which included various modalities such as conventional training, occupational therapy, physical therapy, usual care alone, UL conventional therapy, and conventional rehabilitation. The duration of the VR-based interventions ranged from 2 to 12 weeks, with session durations varying between 30 and 120 min. The average frequency of VR-based training was twice to thrice weekly. Table 1 (Ref. [8, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40]) presents the key characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Country | Stroke duration (month) | Experimental group | Control group | Outcome | |||||||||

| Sample size | Age (year) | Male (%) | Intervention | Each VR (min/session) | VR frequency (times/week) | Total VR (wks) | Sample size | Age (year) | Male (%) | Intervention | ||||

| Park et al., 2019 [32] | Korea | 13 | 53.50 |

53.80 | VR+OT | 30 | 5 | 4 | 13 | 51.50 |

61.50 | OT | FMUE | |

| Rogers et al., 2019 [35] | Australia | 10 | 64.30 |

40.00 | VR+CT | 30 | 3 | 4 | 11 | 64.60 |

45.00 | CT | BBT | |

| Marques-Sule et al., 2021 [30] | Spain | 15 | 61.50 |

60.00 | VR+PT | 30 | 2 | 4 | 14 | 58.20 |

64.30 | PT | FMUE | |

| Ikbali Afsar et al., 2018 [22] | Turkey | 19 | 69.42 |

63.16 | VR+CT | 30 | 5 | 4 | 16 | 63.44 |

50.00 | CT | FMUE, BBT | |

| In et al., 2012 [23] | Korea | 11 | 63.45 |

63.64 | VR+CT | 30 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 64.50 |

50.00 | CT | FMUE, BBT | |

| Yin et al., 2014 [40] | Singapore | 11 | 62.67 |

54.55 | VR+CT | 30 | 5 | 2 | 12 | 56.00 |

83.33 | CT | FMUE | |

| Kim et al., 2018 [24] | Korea | 12 | 56.70 |

58.30 | VR+OT | 30 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 57.20 |

90.90 | OT | FMUE, BBT | |

| Turolla et al., 2013 [39] | Italy | 263 | 60.20 |

60.00 | VR+ULC | 120 | 5 | 4 | 113 | 65.40 |

64.00 | ULC | FMUE, FIM | |

| Kiper et al., 2018 [25] | Italy | 68 | 62.50 |

54.40 | VR+CR | 120 | 5 | 4 | 68 | 66.00 |

63.20 | CR | FMUE, FIM | |

| Patel et al., 2019 [33] | USA | 7 | 57.14 |

71.43 | VR+UC | 60 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 62.00 |

66.67 | UC | FMUE | |

| Choi and Paik, 2018 [18] | Korea | / | 12 | 61.00 |

58.33 | VR+OT | 30 | 5 | 2 | 12 | 72.10 |

60.00 | OT | FMUE |

| Saposnik et al., 2016 [8] | Canada | 71 | 62.00 |

65.00 | VR+CT | 60 | 5 | 2 | 70 | 62.00 |

69.00 | CT | BBT, FIM | |

| Rodríguez-Hernández et al., 2021 [34] | Switzerland | / | 23 | 62.60 |

78.30 | VR+CT | 50 | 5 | 3 | 20 | 63.60 |

85.00 | CT | FMUE |

| Lee et al., 2016 [28] | Korea | 10 | 69.20 |

50.00 | VR+CT | 60 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 73.13 |

37.50 | CT | BBT | |

| Aşkın et al., 2018 [16] | Turkey | 20 | 53.27 |

72.00 | VR+PT | 60 | 5 | 4 | 20 | 56.55 |

70.00 | PT | FMUE, BBT | |

| da Silva Cameirão et al., 2011 [19] | Spain | 10 | 63.00 |

50.00 | VR+CT | 20 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 58.56 |

60.00 | CT | FMUE | |

| Shin et al., 2016 [38] | Korea | / | 24 | 57.20 |

79.20 | VR+OT | 30 | 5 | 4 | 22 | 59.80 |

77.30 | OT | FMUE |

| Kwon et al., 2012 [26] | Korea | 13 | 57.15 |

69.23 | VR+CT | 30 | 5 | 4 | 13 | 57.92 |

38.46 | CT | FMUE | |

| Lee et al., 2016 [27] | Korea | 5 | 62.50 |

60.00 | VR+CR | 30 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 66.20 |

40.00 | CR | FMUE | |

| Choi et al., 2014 [17] | Korea | 10 | 64.30 |

50.00 | VR+OT | 30 | 7 | 4 | 10 | 64.70 |

50.00 | OT | FMUE, BBT | |

| Gueye et al., 2021 [20] | Germany | 25 | 66.56 |

56.00 | VR+PT | 45 | 4 | 3 | 25 | 68.12 |

60.00 | PT | FMUE, FIM | |

| Huang et al., 2022 [21] | China | 15 | 50.80 |

27.00 | VR+OT | 60 | 2–3 | 4 | 15 | 58.33 |

40.00 | OT | FMUE | |

| Huang et al., 2022 [36] | China | 20 | 63.30 |

65.00 | VR+CR | 30 | 5 | 3 | 20 | 65.05 |

55.00 | CR | FMUE | |

| Shin et al., 2015 [37] | Korea | 16 | 53.30 |

68.75 | VR+OT | 30 | 5 | 4 | 16 | 54.60 |

81.25 | OT | FMUE | |

| Long et al., 2020 [29] | China | 30 | 53.28 |

72.00 | VR+CR | 45 | 5 | 3 | 30 | 54.11 |

59.00 | CR | FMUE | |

| Norouzi-Gheidari et al., 2019 [31] | Canada | / | 9 | 42.20 |

55.56 | VR+CT | 40 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 57.60 |

55.56 | CT | FMUE, BBT |

| Ahmad et al., 2019 [15] | Malaysia | 18 | 57.00 |

94.44 | VR+PT | 30 | 1 | 8 | 18 | 62.94 |

77.78 | PT | FMUE | |

Abbreviations: VR, virtual reality; CT, convention training; OT, occupational therapy; PT, physical therapy; UC, usual care alone; ULC, upper limb conventional; CR, conventional rehabilitation; FMUE, Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity; BBT, box and block test; FIM, Functional Independence Measure.

The evaluation was conducted adhered to the risk-of-bias evaluation criteria outlined in the Cochrane Evaluation Manual version 5.1.0 [45]. The methodological quality of the included studies was examined by scrutinizing each dimension of the risk of bias. Notably, all the studies provided complete outcome data. Furthermore, most studies thoroughly reported their approaches for random sequence generation, blinding of outcome assessment, and selective reporting bias; however, only six trials reported blinding of participants, and 14 studies adequately described their method of concealment assignment. Participant blinding in all included trials is unlikely based on the nature of VR-based interventions; however, this lack of blinding does not significantly affect the findings, as the assessment of each outcome indicator is fairly unbiased. Fig. 2 shows the assessments of the included studies.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Overall risk of each type of bias or risk of bias in each study.

The FMUE scores were reported in 24 studies, which included 1140 cases. A

random-effects model was used due to the presence of heterogeneity (p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the effect of virtual reality-based training on FMUE in upper limb dysfunction during post-stroke rehabilitation. IV, Inverse variance; SD, Standard Deviation; CI, Confidence Interval.

Therefore, to further investigate the sources of heterogeneity affecting FMUE, a

meta-regression analysis was conducted to explore whether stroke duration, VR

characteristics, and the type of conventional therapy were associated with the

effect of VR-based training. Stroke duration was divided into three groups (

| Characteristics | Coefficient | t | p | 95% CI |

| Stroke duration (month) | –0.246 | –2.16 | 0.042 | [–0.482, 0.009] |

| VR session duration (min) | 0.000 | –0.03 | 0.973 | [–0.010, 0.010] |

| VR frequency (times per wk) | 0.039 | 0.47 | 0.641 | [–0.132, 0.209] |

| VR period (wks) | –0.098 | 0.35 | 0.726 | [–0.671, 0.475] |

| Conventional therapy | 0.016 | 0.17 | 0.866 | [–0.182, 0.215] |

Note: Stroke duration (month):

| Characteristics | Coefficient | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke duration (month) | –0.344 | –2.22 | 0.041 | [–0.672, 0.017] |

| VR session duration (min) | 0.004 | 0.62 | 0.542 | [–0.009, 0.016] |

| VR frequency (times per wk) | 0.011 | 0.10 | 0.918 | [–0.208, 0.229] |

| VR period (wks) | –0.517 | –1.51 | 0.150 | [–1.241, 0.206] |

| Conventional therapy | 0.056 | 0.50 | 0.627 | [–0.183, 0.296] |

Subsequently, a subgroup analysis of the FMUE was conducted, excluding four

studies (Choi and Paik, 2018 [18]; Rodríguez-Hernández et al.,

2021 [34]; Shin et al., 2016 [38]; Norouzi-Gheidari et al.,

2019 [31]) that did not report stroke duration. The subgroup analysis based on

stroke duration revealed that durations

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

FMUE subgroup analysis of stroke duration.

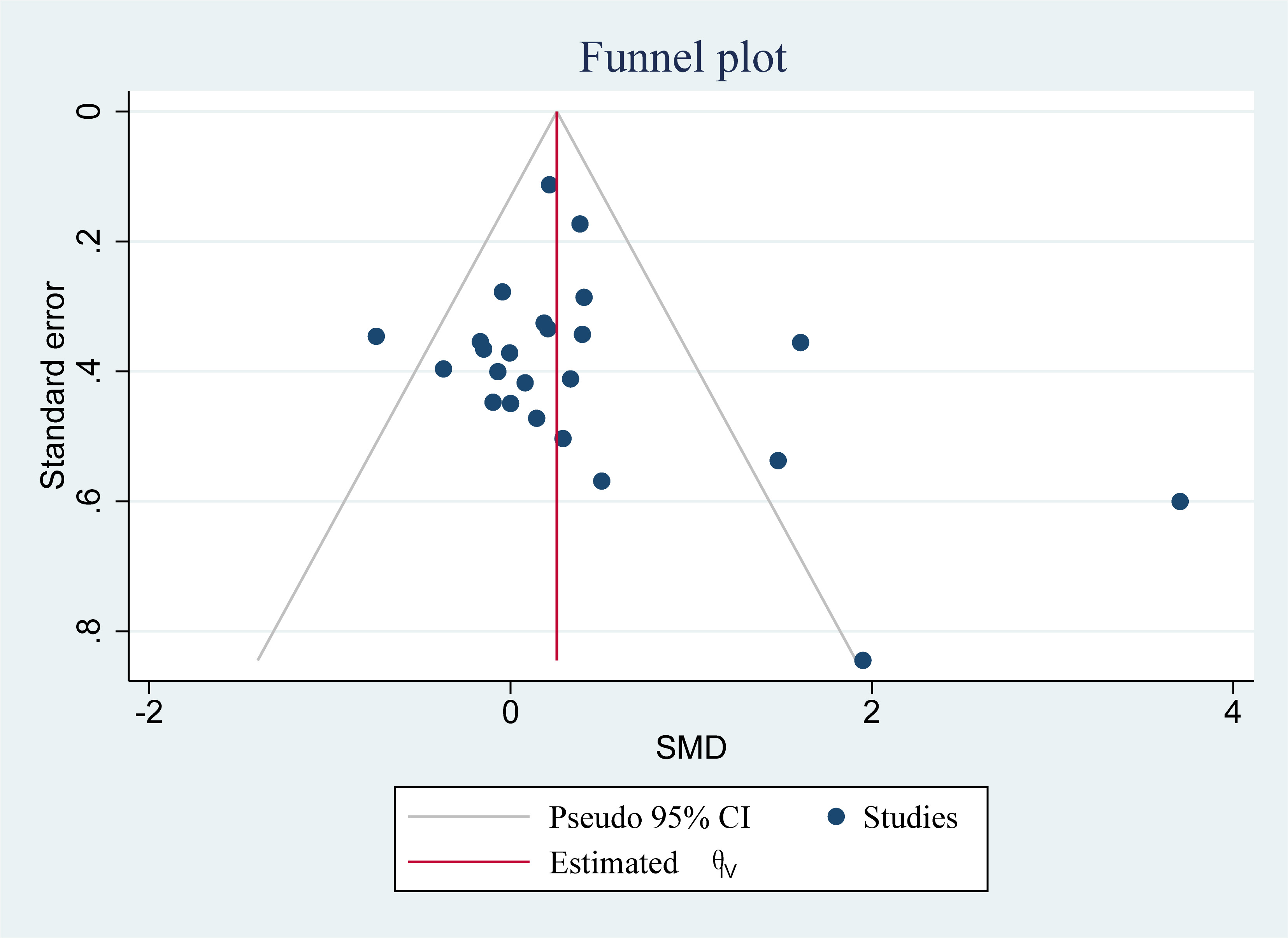

The Cochrane Group suggested using a funnel plot to detect publication bias when at least 10 studies were included. The FMUE analysis, which included 24 studies, met this criterion. Fig. 5 shows a funnel plot of the effect of VR-based training on FMUE in patients with UL dysfunction during post-stroke rehabilitation. Begg’s funnel plot for FMUE demonstrated symmetry and indicated no significant publication bias (p = 0.1303; Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Funnel plot of the effect of virtual reality-based training on FMUE in upper limb dysfunction during post-stroke rehabilitation. SMD, standardized mean difference.

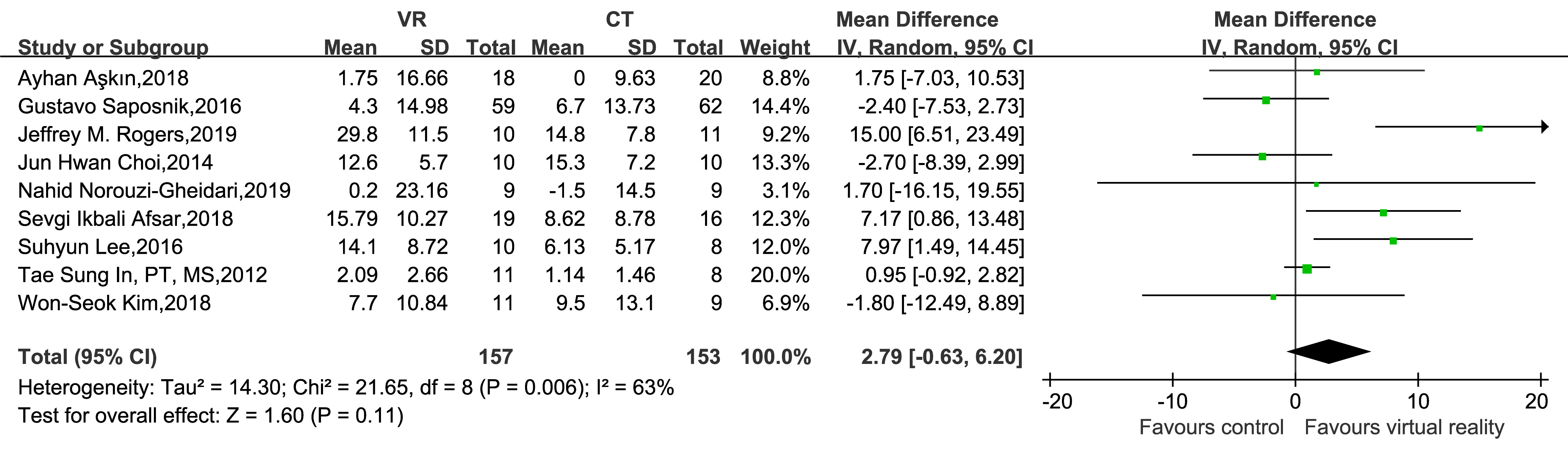

Nine studies (comprising 310 participants) used BBT as an outcome measure. Moderate heterogeneity was detected among the studies (p = 0.006, I2 = 63%); therefore, a random-effects model was adopted for the meta-analytic assessment. The analysis revealed no significant differences in BBT scores between EG and CG concerning activity limitation in UL dysfunction during post-stroke rehabilitation (MD = 2.79, 95% CI: –0.63–6.20, Z = 1.60, p = 0.11; Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of the effect of virtual reality-based training on BBT in upper limb dysfunction during post-stroke rehabilitation. BBT, Box-Block Test.

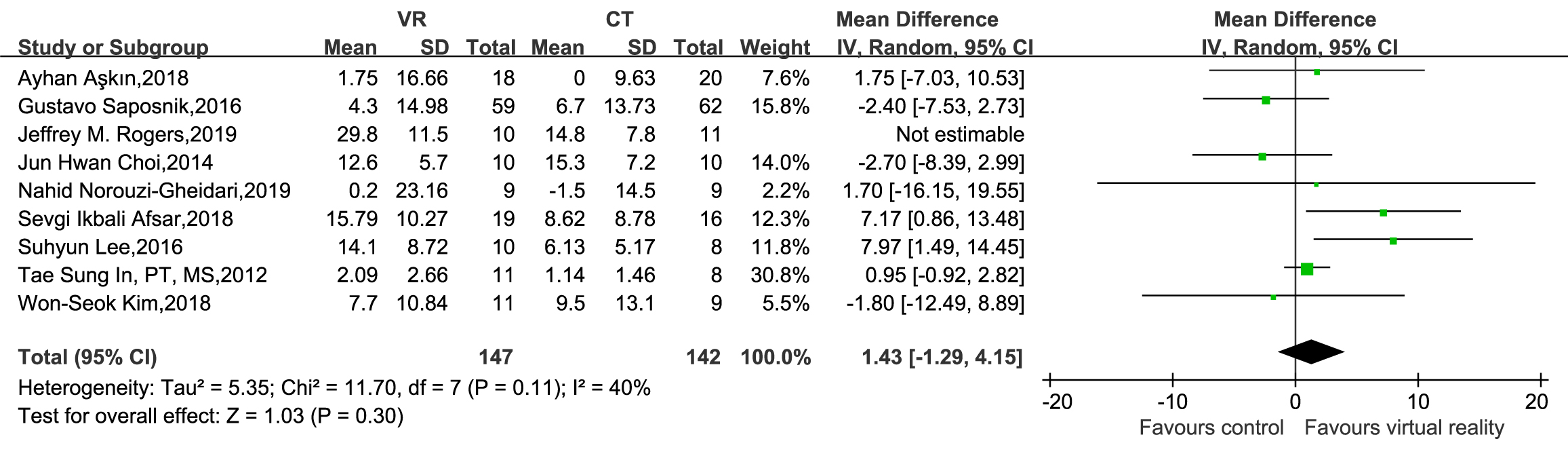

A subsequent sensitivity analysis identified Rogers’s 2019 study [35] as a source of heterogeneity. After excluding this study, the heterogeneity decreased (p = 0.11, I2 = 40%), indicating the stability of all the results (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Sensitivity analysis of BBT.

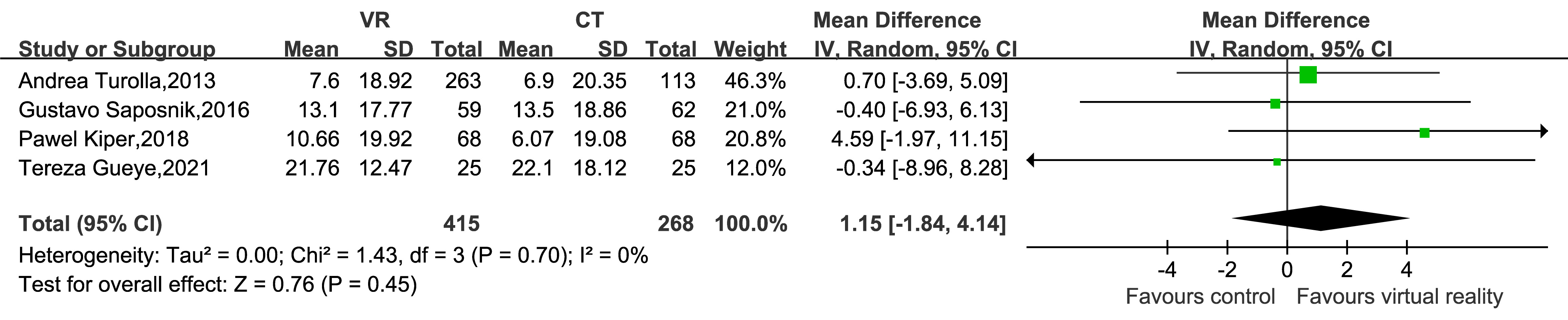

FIM data were reported in four studies, which included 683 patients. The meta-analysis indicated no significant differences in FIM scores between EG and CG regarding functional independence in UL dysfunction during post-stroke rehabilitation (MD = 1.15, 95% CI: –1.84–4.14, Z = 0.76, p = 0.45; Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Forest plot of the effect of virtual reality-based training on FIM in upper limb dysfunction during post-stroke rehabilitation. FIM, Functional Independence Measure scale.

In this study, 27 RCTs involving 1354 patients were included. Our findings

revealed statistically significant differences across various outcome indicators

between conventional therapy plus VR-based training and conventional therapy

alone. Specifically, VR-based training was significantly superior to conventional

therapy for post-stroke UL motor function rehabilitation. Overall, the

meta-analysis of FMUE scores yielded favorable results. Moreover, the

meta-regression and subgroup analyses indicated that stroke duration could

influence the effectiveness of VR-based training on UL function during

post-stroke rehabilitation. Notably, patients with a stroke duration

However, conclusive evidence is unavailable to support the superiority of conventional therapy combined with VR-based training over conventional therapy alone in improving activity limitations and functional independence. Only four studies investigating functional independence showed no significant differences between the EG and CG. However, the lack of statistically significant differences in BBT and FIM scores between the EG and CG in this study should be interpreted cautiously, possibly because of the small sample sizes, which may not have been adequate for detecting potential differences.

Our primary objective in this research was to assess the impact of VR-based training on UL impairment; therefore, we selected the FMUE scale to evaluate UL motor impairment. The FMUE is widely used to assess motor impairment associated with stroke and has been established to possess high validity and reliability [46]. The observed effectiveness of VR-based training on FMUE scores can be attributed to its emphasis on specific motor skills, which are directly addressed in VR environments, fostering neuroplasticity and targeted motor learning. In contrast, the BBT evaluates broader functional capabilities requiring integrated coordination and cognitive engagement [47], which may take longer to manifest as improvement.

Our study further confirmed that the rehabilitative effect of conventional therapy combined with VR-based training significantly surpasses that of conventional therapy alone in improving UL motor function. Consistent with several previous reviews [46, 48, 49, 50, 51], our findings indicate similar improvements in motor impairment. A previous research [52] has demonstrated that VR-based training technology can induce the cortical reorganization of neuromotor pathways. Pre-VR training, bilateral activation occurred in the patient’s primary motor, ipsilateral sensorimotor, and motor accessory area cortices. However, post-training, these areas were inhibited, whereas the contralateral sensorimotor cortical areas were activated, facilitating the compensation and performance of lost motor functions.

However, the findings of a Cochrane review by Laver et al. [11]

contradicted our results. This may be due to discrepancies in the article

inclusion criteria between the two reviews. For instance, Laver et al.

[11] included studies that employed VR combined with robotics, making it

uncertain whether their findings were solely attributable to VR or robotic

training. Similarly, our study, consistent with previous research [53], found a

significantly greater effect of VR-based training on UL motor function in

patients with stroke with durations

Nevertheless, the conclusions drawn from a systematic review conducted by Laver and colleagues [11] were at odds with our own observations. It is plausible that the variance in outcomes stems from variations in the selection criteria for articles between the two reviews. For example, Laver et al. [11] incorporated research that utilized a combination of VR and robotic technology, casting doubt on whether their conclusions were exclusively linked to VR or the robotic aspect of the training. Similarly, our study, consistent with previous research [30], found a significantly greater effect of VR-based training on upper limb motor recovery in stroke survivors who had experienced symptoms for over half a year. This enhanced effect is thought to result from the capacity of VR training to enhance the intensity, repetition, and task-specific nature of exercises within the post-stroke recovery process.

Regarding activity limitations, the benefits of VR were only evident in gross motor function rather than in hand dexterity and flexibility, potentially explaining the negative results in this aspect. This may account for the unfavorable outcomes witnessed in that particular sphere. Such an observation aligns with the conclusions drawn from numerous prior research endeavors [53, 54]. Conversely, the lack of differences in FIM scores may be attributed to the characteristics of the FIM assessment tool [55]. Furthermore, this therapeutic approach may not always influence FIM scores as they encompass aspects such as communication, self-care, and social interaction.

The research incorporated into our analysis failed to adequately differentiate between the degrees of stroke severity and the distinct varieties of VR programs. This lack of distinction precluded a comprehensive examination of the impacts of VR-based rehabilitation on individuals experiencing different levels of stroke severity and different VR applications. Additionally, the variations in duration and frequency across studies limited our ability to fully assess how total dose influences outcomes. These inconsistencies may lead to difficulties in conducting in-depth analysis from the available data. Future research is essential to address these gaps and yield more definitive conclusions.

This study also has some limitations: (1) the inclusion of a narrow range of studies, resulting in a small overall sample size; therefore, implementing double-blinding was challenging due to experimental constraints, potentially introducing bias into the results; (2) only published literature was included, and grey literature was not retrieved, which may have led to publication bias.

One of the most prevalent and widely acknowledged impairments resulting from stroke is UL dysfunction, which focuses on restoring the impaired motor and related functions. Rehabilitation is crucial in helping patients with stroke regain their function. Repetitive task training within VR environments optimizes motor retraining and enhances patient motivation and compliance during rehabilitation. As VR technology advances, future clinical studies with larger sample sizes will aim to explore optimal intervention protocols, including individualized motor presentations, treatment dosages, and the interplay between the two, thereby facilitating the development of personalized rehabilitation training programs. Therefore, we are committed to including more RCTs in subgroup analyses in future studies to explore the efficiency of different types of VR interventions.

Overall, combining conventional therapy with VR-based training is valuable for improving UL motor function in post-stroke patients. Therefore, the advancement of scientific and systematic VR rehabilitation therapy based on conventional therapy can be a method for effectively rehabilitating patients with post-stroke limb disorders in the future.

VR, virtual reality; UL, upper limb; RCT, randomized controlled trials; BBT, Box-Block Test; FMUE, Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity; FIM, Functional Independence Measure scale; EG, experimental group; CG, control group.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

JZ and XJ designed the research. JZ, XJ and QX completed data selection and extraction. EC, HD, JZ and QX contributed to participated in data analysis. XJ, HD and QX participated in writing original draft. JZ, XJ, EC and HD were responsible for revising manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Medical Research Project of Yangzhou Municipal Health Commission (2023-2-23).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.jin2312225.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.