1 Department of Psychology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Rey Juan Carlos University, 28922 Alcorcón, Spain

2 Departament of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Biomedical and Health Sciences, Alfonso X el Sabio University (UAX), 28691 Madrid, Spain

3 Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Medicine, Health and Sports, European University of Madrid, 28670 Villaviciosa de Odón, Spain

4 Department of Physiotherapy, LUNEX International University of Health, Exercise and Sports, 4671 Differdange, Luxembourg

Abstract

This study aimed to explore the true potential of the Spanish Version of the Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI) in a sample of 262 chronic pain patients.

We employed Confirmatory Factor Analysis to evaluate the fit of the data to the factorial solutions most commonly proposed in previous literature. Loadings of items covering the psychological manifestations of central sensitization, in comparison to other manifestations of this phenomenon, were examined. Convergence with psychological measurements was analyzed. Concurrent validity was examined by estimating the wind-up ratio (WUR) values from temporal summation of pain to repetitive pinprick stimulation in a subsample of 87 patients.

A bifactor model with a general factor and four orthogonal factors was the best solution. Loadings on the general factor of items examining the psychological concomitants of central sensitization were significantly higher than those of the items examining physiological symptoms.

Our results indicate that this instrument may be more appropriate to assess aspects associated to cognitive-emotional sensitization or hypervigilance in patients with chronic pain rather than physiological alterations related to sensitization.

Keywords

- chronic pain

- central sensitization

- central sensitization inventory

- temporal summation

- psychophysical tests

- quantitative sensory testing

Central Sensitization (CS), an amplification of neural signaling within the central nervous system eliciting pain hypersensitivity, it’s significant in chronic pain and is considered a key mechanism explaining the transition and perpetuation of pain in different chronic conditions (den Boer et al, 2019; Villafañe et al, 2019). Several physiological mechanisms are involved, such as the facilitation of temporal summation of pain (TS) and/or impairment of conditioned pain modulation (CPM) (den Boer et al, 2019; Nijs et al, 2021a; Villafañe et al, 2013). Moreover, psychological factors also play a role, namely depression, anxiety, catastrophizing and hypervigilance, among others (Arendt-Nielsen et al, 2018). TS refers to the surrogate model of explanation of the windup phenomena observed in preclinical studies. This windup mechanism reflects the process of homosynaptic facilitation between the first and second order neurons at the spinal cord in response to noxious/non- noxious stimuli, resulting in primary hyperalgesia, as well as expansion of receptive fields (secondary hyperalgesia) (Hoegh, 2023a; Hoegh, 2023b; Woolf, 2011). As a correlate, TS reflects an increase in the excitability of dorsal horn neurons due to repetitive noxious stimulation of C/A

The evaluation of the presence of central sensitization is usually done using two different types of measures. On the one side, self-report instruments, most remarkably the Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI), have been employed to assess the different symptoms typically present in patients suffering CS (Mayer et al, 2012), providing a wide range of evidence on different populations with different proposed factorial structures. The original development for English speakers was conducted in a chronic pain sample of patients with fibromyalgia (FM), chronic widespread pain without FM, chronic low back pain and healthy controls (HC). This study initially found a 4-factor structure including physical, emotional, jaw/headache and urological symptoms (Mayer et al, 2012). This same factorial solution has been observed by other authors in populations with different forms of chronic musculoskeletal pain, namely Dutch (unspecified chronic pain sample) (Kregel et al, 2016), Portuguese (adolescents, non-specified chronic pain sample) (Andias and Silva, 2020) or Brazilian (osteoarthritis, myofascial pain syndrome, chronic tension-type headache, fibromyalgia and HC) (Caumo et al, 2017). Apart from slight differences in nomenclature, these studies also describe factors with items that were essentially the same as those in the original one. Furthermore, all of these studies include several CSI items under the category of ‘emotional distress’ as one of the factors, just like the original version by Mayer.

Beyond the previously mentioned 4-factor structure, other specific samples have been tested obtaining different solutions, e.g., Spanish cancer survivors (1-factor structure) (Roldán-Jiménez et al, 2021) or knee osteoarthritis Korean patients (6-factor structure) (Kim et al, 2020). Regarding the original Spanish version, examined on subjects with low back pain, neck pain, knee pain, back pain and osteoarthritis, a 1-factor solution was obtained, where all items reflecting signs and symptoms compatible with the whole central sensitization construct (Cuesta-Vargas et al, 2016).

Moreover, the bifactor structure seems to be also one of the most appropriate solutions for this questionnaire, in which a general factor (general CS factor) is able to cover all central sensitization features, but with 4-orthogonal factors (including a factor covering emotional characteristics). This has been shown in a pooled multi-country sample (Cuesta-Vargas et al, 2018), and in the German adaptation in patients with different pain disorders, such as fibromyalgia, multisite chronic pain, chronic back and neck pain, rheumatoid arthritis, regional chronic pain, and healthy controls (Klute et al, 2021).

About the possible impact of demographic variables on CSI scoring, sex may play a role, with higher but weak scores in women compared to men (Klute et al, 2021), or, in contrast significantly higher in older women (Ide et al, 2021). For age, correlations have been shown to be non-significant or weak (Klute et al, 2021; Schuttert et al, 2023). Despite this, to the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence of different factor structures depending on sociodemographic variables.

On the other side, alternatively to the use of psychometric measures, psychophysical tests such as the Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST) have been proposed as surrogate measures of central pain mechanisms and are used to estimate the presence and magnitude of CS. Specifically, pressure pain thresholds (PPT), different protocols for the evaluation of CPM and TS of pain have been used (den Boer et al, 2019; Villafañe et al, 2013).

There is emerging evidence regarding the predictive value for central sensitization of both the CSI and psychophysical tests. However, conflicting findings for CSI have been shown in several musculoskeletal conditions (Cliton Bezerra et al, 2021; Gervais-Hupé et al, 2018; Proença et al, 2021). Recently, a meta-analysis by Adams et al. (2023), concluded there is no strong evidence to suggest that the CSI reflects CS, arguing that this tool seems to identify people with a psychological vulnerability that is associated with pain (a hypervigilant state that is common in many patients with chronic pain), rather than with CS itself (Adams et al, 2023).

The primary objective of this study was to delve into the validity of the Spanish version of the CSI, ensuring it is both culturally appropriate and structurally sound for Spanish-speaking populations. Firstly, the best factorial solution for the Spanish version was examined. This was followed by analyzing the reliability of the scale. Secondly, the study assessed the convergence between CSI scores and other self-report measures capturing psychological phenomena related to central sensitization. We also tested the concurrence with a psychophysical test associated with CS findings: the facilitation of TS. While the original goal of the Spanish validation study was to culturally adapt the CSI for the European Spanish language, no analysis of criterion-related validity was ever conducted (Cuesta-Vargas et al, 2016). According to the results by Adams et al. (2023), a predominance of items covering the psychological symptoms contributing to the measurement of CS was expected, in comparison to those focused on the physiological symptoms. We expected a higher convergence of the CSI with the measurements of psychological phenomena in the domain of CS, rather than with the measurements of the physiological component of CS (Adams et al, 2023).

This was an observational study with a cross-sectional design, following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) recommendations (von Elm et al, 2014). It was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Móstoles in Spain (06-30-2021, approval number 2020/048). All participants enrolled in the study gave written informed consent to participate. The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

The study was conducted in the Pain Management Unit of the University Hospital of Móstoles, between July 2021 and July 2022. In the one-day study, several self-administered questionnaires were completed by a total sample of 262 consecutive adults (+18), they were all patients suffering diverse chronic pain conditions (persistent or recurrent pain lasting longer than 3 months) who had been referred to a Pain Management Unit of a large hospital in Spain. The exclusion criteria were to be suffering from heart failure, dermatological or mental diseases, pregnancy, and showing poor Spanish language comprehension. Quantitative Sensory Testing was performed in a subsample of 87 participants incidentally selected among those willing to participate. The intensity of pain was evaluated using a numerical rating scale (NRS) and the duration of the symptoms was also registered.

Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI). The original English version was developed by Mayer et al. (2012) on 451 subjects and validated into several languages and cultures, including Brazilian-Portuguese (Caumo et al, 2017), Dutch (Kregel et al, 2016), French (Pitance et al, 2016), Italian (Chiarotto et al, 2018) and Spanish (Cuesta-Vargas et al, 2016), among others. In addition, the combination of data coming from these studies were analyzed in a pooled multi-country study (Cuesta-Vargas et al, 2018).

The CSI consists of a self-administered questionnaire with two different parts. Part A consists of 25 items assessing different symptoms usually present in chronic pain patients with central sensitization features. Using a five-point Likert Scale, patients respond to the degree of severity of these symptoms. The scale scores range between 0 and 100, with 40 points as a cut-off indicating the possible involvement of central sensitization (Neblett et al, 2013). In Part B, patients can indicate if they suffer several chronic pain diagnoses compatible with CS conditions.

Multiple factor structure solutions have been proposed in the diverse adaptations of the scale, namely a four-factor structure (representing physical symptoms, emotional distress, jaw/headache symptoms and urological symptoms theoretically linked to central sensitization) (Andias and Silva, 2020; Mayer et al, 2012; Pitance et al, 2016), a one-factor structure representing general central sensitization (Chiarotto et al, 2018; Düzce Keleş et al, 2021), or a bifactor structure (combining the general factor plus the four additional group factors) in a pooled multi-country sample with 1987 participants (Cuesta-Vargas et al, 2018). Specifically, for the Spanish version, a one-factor solution was the best solution in the study by Cuesta-Vargas et al. (2016). The CSI has shown very good reliability throughout the different versions of the scale (Andias and Silva, 2020; Cuesta-Vargas et al, 2018; Feng et al, 2022). In particular, the Spanish version (Cuesta-Vargas et al, 2016) showed high internal consistency (Cronbach Alpha = 0.872) and a high test-retest reliability (r = 0.91), for the general scale coming from the one factor solution. This version was intended to be based on previous evidence on the utility of the CSI in chronic samples (Neblett et al, 2015). Nonetheless, the authors did not mention prior evidence on concurrent validity of the instrument, including its concurrence with the psychophysical performance of participants.

Other self-report questionnaires. To examine the convergence of central sensitization scores with other psychological features several self-administered questionnaires were included, namely the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) (Quintana et al, 2003), the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) (García Campayo et al, 2008), the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI) (Sandin et al, 1996), the Highly Sensitive Person Scale (HSPS) (Smolewska et al, 2006) and the Negative dimension of the Positive Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (Díaz-García et al, 2020).

256 mN PinPrick Stimulator (MRC Systems GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). The 256 mN PinPrick stimulator was used to assess mechanical pain sensitivity through quantitative sensory testing (QST). This device applies a calibrated force of 256 millinewtons via a standardized 0.25 mm diameter metal tip, designed to activate cutaneous nociceptors without causing tissue damage. Its use enables precise and reproducible stimulation, suitable for detecting phenomena such as hyperalgesia or mechanical allodynia. This model is part of the validated set by the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (DFNS) and is widely used in clinical and research settings due to its reliability and standardization.

Temporal Summation (TS) was evaluated by pinprick stimulation. This psychophysical test was performed to assess the presence of TS facilitation as the human surrogate of windup phenomena, a feature observed in central sensitization (den Boer et al, 2019; Weaver et al, 2022). TS reflects increased excitability of neurons in the dorsal horn by repetitive stimulation of C/A

Differences between the total sample and the Quantitative Sensory Testing subsample in sociodemographic and clinical variables were examined. Gender distribution differences were analyzed using a chi-square test. For age, intensity of pain (numeric rating scale, NRS), and duration of symptoms, t-tests for the difference between means were employed, and Cohen’s d effect sizes were computed.

The data set distribution was assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In cases of non-normality, univariate outliers were identified using standardized scores exceeding 3.29 (p

Different factor structures for the Spanish CSI were tested using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) on the whole sample of 262 participants. This sample size was enough to conduct CFA (Myers et al, 2011; Wolf et al, 2013). In spite of the data’s non-normality, Maximum Likelihood estimation was used to determine factor weight estimates due to its potential advantages over other methods, even though it is not as robust to non-normality (Kilic and Dogan, 2021; Kilic et al, 2020). However, it was complemented with bootstrapping, for which 2000 bootstrap replications were used. Three models were evaluated: a 4-factor model (original English version), a 1-factor model (Spanish validation), and a bifactor model. Fit indices such as chi-square, the Bollen-Stine corrected p value of the chi-square (Byrne, 2010), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) were calculated using AMOS 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences in

To examine convergent validity, correlations between the CSI and self-reported psychological variables were estimated. After analyzing outliers in the wind-up ratio measurements, concurrent validity was examined by calculating Pearson correlations with CSI scores on the subsample of 87 participants. Additionally, a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was used to determine whether the 40-point cut-off in the CSI could discriminate patients with potential central sensitization involvement, based on the results of the temporal summation (pinprick) assessment.

The Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied, setting statistical significance at p

The sample comprised 262 patients, 172 of them were women (65.6%) and 90 were men (34.4%), with a mean age of 58.59 (

Non-normal distributions were observed in 13 items of the CSI (items 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 11, 14, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25), in the general index of the PCS and its dimensions, and in the general index of the ASI and its somatic and cognitive dimensions. Only two outliers were detected in items 11 and 20 of the CSI (z scores

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (0.889) and Bartlett’s Sphericity Test [

| Model | χ2 | df | p-value χ2 | diff χ2/df | p-value diff χ2/df | B-S | RMSEA | TLI (NNFI) | CFI |

| 1-factor | 778.835 | 275 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.73 | 0.75 | ||

| 4-factor | 663.711 | 269 | 0.000 | 115.124/6 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.80 | |

| Bifactor | 428.929 | 244 | 0.000 | 234.782/25 | 0.002 | 0.05 | 0.89 | 0.91 |

Note.

Table 2 shows the factor loadings in the bifactor model. Loadings for all items within the General Factor model yielded values above the 0.4 cutoff, as proposed by Mayer et al. (2012), ranging from 0.41 to 0.68, except for items 11, 20, 21, and 25. Importantly, the Emotional Distress items within the General Factor showed the best factor loadings.

| Central sensitization items | Bifactor model | ||||

| General Factor | Physical Symptoms | Emotional Distress | Headache/Jaw Symptoms | Urological Symptoms | |

| 1. I feel unrefreshed when I wake up in the morning | 0.61 | 0.26 | |||

| 2. My muscles feel stiff and achy | 0.57 | 0.26 | |||

| 3. I have anxiety attacks | 0.41 | 0.29 | |||

| 4. I grind or clench my teeth | 0.55 | 0.59 | |||

| 5. I have problems with diarrhea and/or constipation | 0.49 | –0.01 | |||

| 6. I need help in performing my daily activities | 0.44 | 0.48 | |||

| 7. I am sensitive to bright lights | 0.53 | 0.06 | |||

| 8. I get tired very easily when I am physically active | 0.55 | 0.51 | |||

| 9. I feel pain all over my body | 0.63 | 0.19 | |||

| 10. I have headaches | 0.47 | 0.22 | |||

| 11. I feel discomfort in my bladder and/or burning when I urinate | 0.32 | 0.35 | |||

| 12. I do not sleep well | 0.49 | –0.11 | |||

| 13. I have difficulty concentrating | 0.67 | –0.33 | |||

| 14. I have skin problems such as dryness, itchiness, or rashes | 0.44 | 0.04 | |||

| 15. Stress makes my physical symptoms get worse | 0.68 | 0.16 | |||

| 16. I feel sad or depressed | 0.63 | 0.25 | |||

| 17. I have low energy | 0.67 | 0.47 | |||

| 18. I have muscle tension in my neck and shoulders | 0.58 | –0.21 | |||

| 19. I have pain in my jaw | 0.56 | 0.57 | |||

| 20. Certain smells, such as perfumes, make me feel dizzy and nauseated | 0.36 | 0.03 | |||

| 21. I have to urinate frequently | 0.27 | 0.72 | |||

| 22. My legs feel uncomfortable and restless when I am trying to go to sleep at night | 0.52 | 0.06 | |||

| 23. I have difficulty remembering things | 0.57 | –0.56 | |||

| 24. I suffered trauma as a child | 0.41 | –0.09 | |||

| 25. I have pain in my pelvic area | 0.30 | 0.20 | |||

| Cronbach Alpha ( | 0.898 | 0.834 | 0.731 | 0.698 | 0.477 |

| McDonald’s Omega (ω) | 0.900 | 0.843 | 0.735 | 0.711 | 0.510 |

Data of internal consistency from the Central Sensitization Inventory are also presented in Table 2. The total score of the CSI (0.898) showed good internal consistency (Terwee et al, 2007). Furthermore, Cronbach

Correlations between the Central Sensitization Inventory and self-reported psychological variables are presented in Table 3. All correlations were high and positive, ranging from 0.39 (ASI-somatic) to 0.68 (HADS-anxiety) for the total score (general factor) of the CSI. Correlations between CSI subscales and psychological variables were also high for CSI-Physical Symptoms and CSI-Emotional Distress, ranging from 0.36 to 0.68. Correlations of psychological variables with CSI-Headache/Jaw and CSI-Urological symptoms were, however, lower, ranging from 0.17 to 0.49.

| HADS | HADSA | HADSD | PCS | PCSR | PCSM | PCSH | ASI | ASIS | ASIC | ASIs | HSPS | PANAS | |

| CSI total | 0.676* | 0.681* | 0.542* | 0.497* | 0.410* | 0.432* | 0.522* | 0.443* | 0.398* | 0.402* | 0.403* | 0.569* | 0.527* |

| CSI-PS | 0.663* | 0.626* | 0.574* | 0.508* | 0.414* | 0.430* | 0.543* | 0.420* | 0.391* | 0.364* | 0.380* | 0.478* | 0.458* |

| CSI-ED | 0.693* | 0.692* | 0.562* | 0.512* | 0.423* | 0.465* | 0.528* | 0.436* | 0.377* | 0.442* | 0.360* | 0.539* | 0.580* |

| CSI-HS | 0.389* | 0.492* | 0.210* | 0.256* | 0.215* | 0.216* | 0.270* | 0.283* | 0.254* | 0.243* | 0.278* | 0.491* | 0.369* |

| CSI-US | 0.300* | 0.294* | 0.249* | 0.195* | 0.173* | 0.182* | 0.191* | 0.230* | 0.187* | 0.210* | 0.250* | 0.334* | 0.255* |

Note. *: Pearson correlation coefficient are significant at the level 0.0008 (Bonferroni correction); CSI total, total score of CSI; CSI-PS, CSI Physical Symptoms; CSI-ED, CSI Emotional Distress; CSI-HS, CSI Headache/Jaw Symptoms; CSI-US, CSI Urological Symptoms; HADS, Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale; HADSA, Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale Anxiety; HADSD, Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale Depression; PCS, Pain Catastrophizing Scale; PCSR, PCS Rumination; PCSM, PCS Magnification; PCSH, PCS Helplessness; ASI, Anxiety Sensitivity Index; ASIS, ASI Somatic; ASIC, ASI Cognitive; ASIs, ASI social; HSPS, Highly Sensitive Person Scale; PANAS, negative dimension of Positive and Negative Affect Schedule.

Prior to analyzing the concurrence between the Central Sensitization Inventory and wind-up ratio (WUR) measurements, outlier detection was carried out for WUR scores. From the total temporal summation subsample (n = 87), six single pinprick values were identified as outliers (z scores

| WUR 1 | WUR 2 | WUR 3 | WUR 4 | WUR 5 | ||

| WUR 1 | r | NA | ||||

| N | 73 | |||||

| WUR 2 | r | 0.540* | NA | |||

| N | 69 | 76 | ||||

| WUR 3 | r | 0.530* | 0.585* | NA | ||

| N | 70 | 72 | 76 | |||

| WUR 4 | r | 0.396* | 0.678* | 0.443* | NA | |

| N | 70 | 73 | 74 | 78 | ||

| WUR 5 | r | 0.451* | 0.529* | 0.473* | 0.632* | NA |

| N | 71 | 75 | 74 | 75 | 78 | |

| WUR mean | r | 0.727* | 0.825* | 0.700* | 0.858* | 0.827* |

| N | 73 | 75 | 76 | 78 | 78 | |

Note. *: Pearson correlation coefficient (r) significant at the level 0.003 (Bonferroni correction). TS, Temporal Summation; WUR, wind-up ratio; NA, Not applicable. Each correlation has different samples depending on the number of patients responding 0 in individual pinprick pain rating and outliers treated as missing data.

| Descriptive analysis of WUR | Pearson’s correlations between CSI and wind-up ratio measurements | |||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Total score | CSI-PS | CSI-ED | CSI-HS | CSI-US | |

| WUR 1 | 73 | 2.5766 | 1.67009 | 1.666 | 2.967 | 0.271 | 0.314† | 0.294† | –0.001 | 0.171 |

| WUR 2 | 76 | 2.2513 | 1.36147 | 1.515 | 2.955 | 0.218 | 0.211 | 0.249 | 0.093 | 0.104 |

| WUR 3 | 76 | 2.4974 | 1.52067 | 1.665 | 2.927 | 0.149 | 0.153 | 0.132 | 0.087 | 0.075 |

| WUR 4 | 79 | 2.7912 | 2.11241 | 1.864 | 2.958 | 0.150 | 0.175 | 0.155 | –0.004 | 0.109 |

| WUR 5 | 80 | 2.9942 | 2.03916 | 1.648 | 2.756 | 0.253 | 0.220 | 0.325 | 0.096 | 0.144 |

| WUR mean | 81 | 2.7230 | 1.53685 | 1.478 | 2.075 | 0.225 | 0.213 | 0.267† | 0.077 | 0.133 |

Note. †: Pearson correlation coefficient are significant at the level 0.01; WUR, wind-up ratio (number indicates the series). WUR mean, mean of the five wind-up ratio series; CSI-PS, CSI Physical Symptoms; CSI-ED, CSI Emotional Distress; CSI-HS, CSI Headache/Jaw Symptoms; CSI-US, CSI Urological Symptoms. No significant correlations were observed at the 0.002 level (Bonferroni correction).

Table 4 shows the correlations between the five series of the WUR. They were significant, especially yielding a strong correlation between WUR mean and all individual measurements. In fact, the five independent measurements, taken together, showed good internal consistency (

Correlations between Central Sensitization Inventory scores and wind-up ratio measurements are presented in Table 5. Correlations with p-values below 0.01 were only observed between the CSI ‘Physical Symptoms’ subscale (CSI-PS) and the first WUR series, and between the ‘Emotional Distress’ subscale (CSI-ED) and the first and fifth WUR series, respectively. However, they were far from being significant once the Bonferroni correction was applied (p

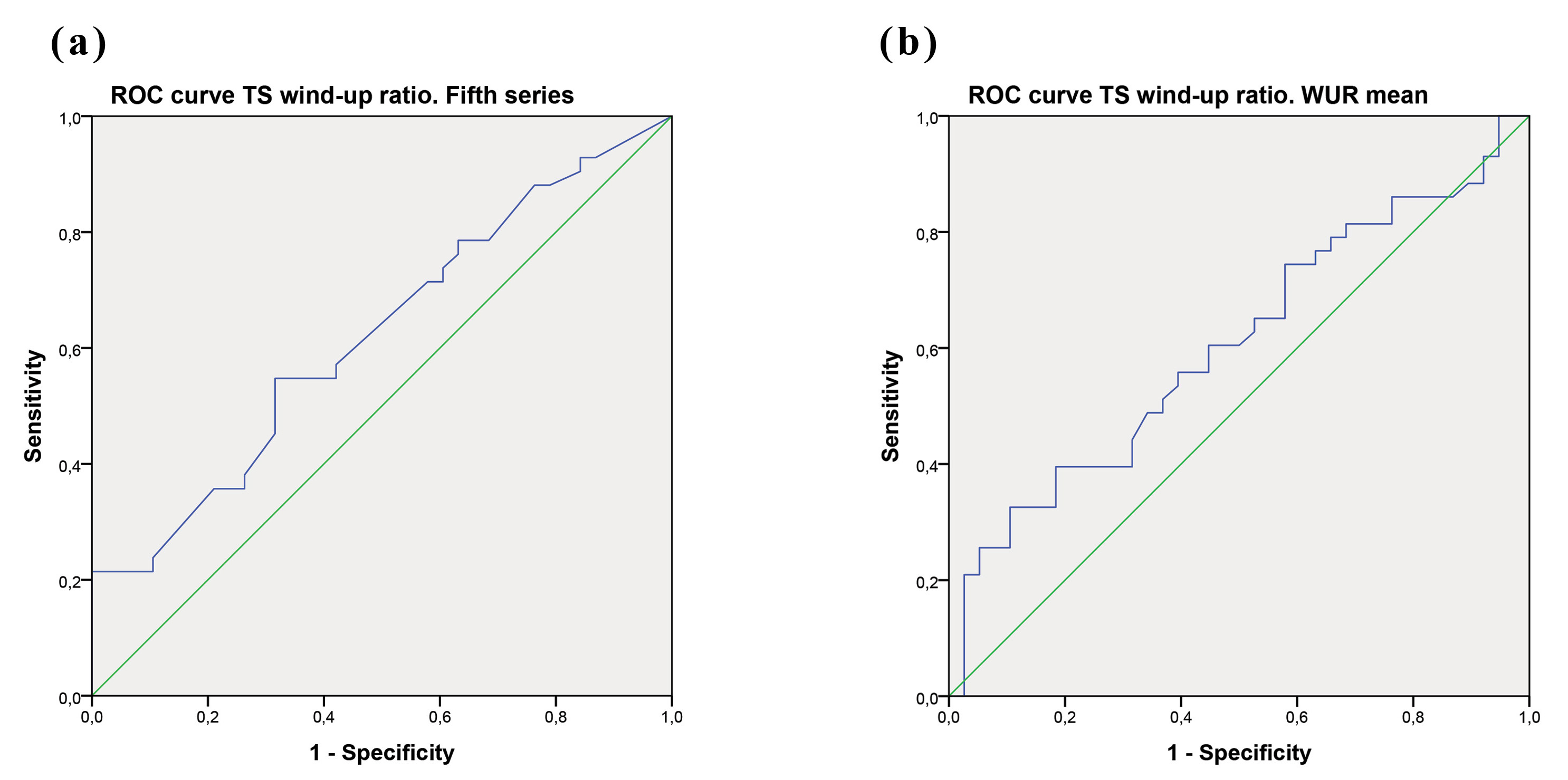

Finally, ROC curve analysis showed non-significant association for the WUR mean (area under the curve (AUC) = 0.606; p = 0.103) by using the CSI dichotomic cutoff (

| N (total) | N = | N = | AUC | Sig. | |

| WUR 1 | 73 | 34 | 39 | 0.538 | 0.573 |

| WUR 2 | 76 | 37 | 39 | 0.576 | 0.255 |

| WUR 3 | 76 | 35 | 41 | 0.541 | 0.542 |

| WUR 4 | 79 | 37 | 42 | 0.547 | 0.470 |

| WUR 5 | 80 | 38 | 42 | 0.621 | 0.063 |

| WUR mean | 81 | 38 | 43 | 0.606 | 0.103 |

Note. WUR, wind-up ratio; ROC, Receiver Operating Characteristic; AUC, Area Under the Curve; Sig., significance (p value).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. ROC curve TS wind-up ratio for the fifth series (a) and WUR mean (b).

The findings of this study contribute to our understanding of the psychometric properties and criterion validity of the Spanish version of the Central Sensitization Inventory and, in consequence, to our knowledge regarding its potential to measure central sensitization. Our data suggest, in accordance with previous research (Adams et al, 2023), that the Spanish version of the CSI is more adequate to assess cognitive-emotional aspects of CS rather than physiological factors.

The CFA supported the bifactor structure as the best solution for the Spanish version, contradicting the original Spanish validation study on 395 subjects by Cuesta-Vargas et al. (2016), but in line with the second big study with a pooled multicountry sample (n = 1033) by Cuesta-Vargas et al. (2018), or for the German adaptation by Klute et al. (2021). The bifactor model fitted better than the other models, suggesting the existence of four latent factors (Physical Symptoms, Emotional Distress, Headache/Jaw Symptoms and For Urological Symptoms) encompassing specific features, along with a general factor for what is common to central sensitization. Unsurprisingly, the loadings for the general factor of the items examining the psychological concomitants of CS were significantly higher than for the items examining the physiological symptoms. This leads to questioning the true nature of this general factor that theoretically is aimed at measuring CS (Adams et al, 2023).

Regarding the concurrence between the Central Sensitization Inventory scores and TS results, although we found correlations with p-values below 0.01 between the emotional factor of the instrument (CSI-ED) and the first and fifth WUR series, they were not significant once the Bonferroni correction was applied. Plus, by using the 40-point cutoff of the CSI scores as the criteria for determining the presence or absence of central sensitization, the ROC curve showed a non-significant association with any WUR measurement. The best performance was observed for the models corresponding to the fifth series and the WUR mean. Overall, these findings showed a limited capacity of the CSI for the prediction of TS, reinforcing the idea of the weakness of this tool in correlating with psychophysical testing, but rather with psychological features. Specially, this ability was however clearly insufficient when using the CSI for binary classification purposes. This aspect of the CSI may be interpreted as new evidence of the lack of canonical understanding of CS claimed by Adams et al. (2023).

The total score (general factor) of the Central Sensitization Inventory yielded positive and significant correlations (above 0.5 in most of the cases) with all measurements of psychological variables commonly identified as closely linked to central sensitization (p

Our data suggests that the Spanish version of the Central Sensitization Inventory, like the original tool and its successive adaptations to other languages, does not strictly measure the physiological aspects of central sensitization, but rather a psychological disturbance that usually comes along with CS or, in the words of Adams et al. (2023), a “psychological hypervigilance that increases responsiveness of nociceptive neurons”. Several of our findings support this. Firstly, we found that there were higher loadings of the items measuring the psychological symptoms of CS. Secondly, correlations between the CSI and wind-up ratio measurements were not found. Furthermore, the fact that the ROC curve showed non-significant associations with any WUR measurement, and the positive and significant correlations observed with all psychological measurements all supported this idea.

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, a larger presence of mild severity chronic pain patients and/or healthy participants would have been desirable, this would help to know more about the potential of the scale for classificatory purposes, as this scale could only have the potential to discriminate between healthy people and chronic pain patients in line with what has been recently claimed by Adams et al. (2023). Secondly, in relation to the management of the sample: we approached the sample like an undifferentiated chronic pain group of participants. A larger sample with an adequate representation of diverse chronic pain disorders might be useful to increase the external validity of the study, increasing the power of the factorial solution and making it comparable to those of the large samples used in pooled multi-country approaches (even though these are samples not circumscribed to a single speaking population, as this study is). Third, despite TS being the most important among the surrogate measures of central sensitization, so far it is impossible to directly measure CS (Quesada et al, 2021). An optimal method to able to assess the construct validity of the Central Sensitization Inventory as an accurate indicator of CS in humans is yet to come. Finally, the design of this study was cross-sectional, with a single one-day evaluation, further studies with a cohort design and repetitive assessments should be carried out. In conclusion, our study contributes to the emerging literature evidencing that the CSI should not be a canonical measurement of CS (Adams et al, 2023; Cliton Bezerra et al, 2021; Matesanz-García et al, 2022).

The Spanish version of the CSI exhibits outstanding correlations with psychological measures and a doubtful predictive capacity for TS assessments. It is possible that this instrument is more appropriate for evaluating aspects related to cognitive-emotional sensitization or hypervigilance, rather than physiological alterations associated to sensitization. In this regard, considering the context of the different professionals involved in the management of a patient with chronic pain, the CSI can be both appropriate and applicable to assess the presence of CS in clinical practice. Therefore, it can be considered as a relevant tool not only in medical contexts, but also for other health professionals, where, for example, the role of psychologists specializing in this type of patient is fundamental to understanding central sensitization. For instance, it is noteworthy that higher CSI scores in cancer survivors correlate with higher levels of catastrophizing (De Groef et al, 2017, 2018). Similarly, the convergent validity of the instrument has been demonstrated with severity measures specific to FM, a condition with a high cognitive-emotional burden.

In conclusion, we recommend the use of this instrument with caution when measuring central sensitization and always within a multi-method approach. In our opinion, in the field of self-report assessments there is an urgent need to develop more suitable methods of evaluation for CS, especially in regards to the recent insights about what it actually is. Meanwhile, CSI is intended as a useful tool for identifying, within the clinical assessment of patients with chronic pain, those who exhibit particularly significant cognitive-emotional sensitization—a common feature of nociplastic pain, primarily driven by central sensitization—serving as an indicator that warrants further evaluation of the physiological component (Fitzcharles et al, 2021; Neblett et al, 2024; Nijs et al, 2021b).

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the OSF repository https://osf.io/2x3rd/.

Design: MALdP, JLGG and ALL; sample and assessment: MALdP; data analysis: MALdP and JLGG; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work: JHV and CC; supervision writing original manuscript: all authors (MALdP, JLGG, JHV, CC, ALL). All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Research approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Móstoles (06-30-2021, approval number 2020/048). All participants enrolled in the study gave written informed consent to participate.

The authors thank the participation of all patients and the assistance of all staff of the Pain Management Unit of the University Hospital of Móstoles.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/BP45892.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.