Academic Editor: Peter A. McCullough

Left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction and systolic anterior motion

(SAM) of the mitral valve (MV) occurs in 70% of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

(HCM) patients. In individuals undergoing septal myectomy, concomitant MV surgery

is considered for SAM with residual LVOT obstruction or mitral regurgitation

(MR); however, the optimal approach remains debated. A literature search was

performed in Pubmed, EMBASE, Ovid, and the Cochrane library of published articles

through June 2021 reporting on combined septal myectomy and edge-to-edge MV

repair for obstructive HCM. Continuous variables were weighted and compared using

a student’s t-test, and categorical variables using a chi-square test

with Yates correction. Six studies with 158 total patients were included. The

mean follow-up was 2.8

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetic disorder with a prevalence of 1 in 200 to 500, a heterogeneous phenotypic expression, and a widely variable clinical course [1, 2]. It is characterized by left ventricular (LV) wall thickening and hypertrophy, which is often in an asymmetric pattern and may be associated with abnormalities of the mitral valve (MV) and subvalvular apparatus [3]. Approximately 70% of HCM patients have left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction secondary to LV hypertrophy, anatomic narrowing of the LVOT, and systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the MV [4, 5, 6]. As a result, patients present with dyspnea, angina, or syncope, and significant mitral regurgitation is a common co-morbidity [3, 7].

Individuals with symptomatic obstructive HCM on maximally-tolerated guideline-directed medical therapy may undergo septal myectomy to relieve LVOT obstruction, reduce heart failure symptomatology, and improve quality of life [8, 9]. Concomitant MV surgery is considered in cases of valvular pathology, severe SAM with residual LVOT obstruction, or significant mitral regurgitation (MR). One approach is the performance of an edge-to-edge MV repair (‘Alfieri stitch’) which approximates the anterior and posterior leaflets at their A2 and P2 scallops, respectively [10]. This anchors the MV coaptation point more central in the LV cavity and limits anterior leaflet excursion into the LVOT, thereby reducing SAM. While use of the edge-to-edge MV repair in primary and secondary MR has been well described, the literature regarding outcomes in obstructive HCM are less robust [11, 12, 13, 14].

In the present systematic review, we sought to assess the published studies on combined septal myectomy and edge-to-edge MV repair for patients with refractory obstructive HCM, with a focus on echocardiographic and clinical outcome measures.

The study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [15, 16]. A systematic literature review was performed, using Pubmed, EMBASE, Ovid, and the Cochrane library, of all scientific articles published through June 2021. The search terms were: [(hypertrophic cardiomyopathy OR hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy OR HOCM) AND (edge-to-edge OR edge-to-edge repair OR E2E OR Alfieri OR Alfieri stitch)]. Two authors (C.G.M., E.E.) independently screened the identified studies, as well as the cited references of each study to ensure the inclusion of all relevant publications. The criteria for study inclusion in the systematic review were: (1) patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM; (2) performance of septal myectomy for relief of LVOT obstruction; and, (3) concomitant use of an edge-to-edge MV repair. The exclusion criteria were non-English language studies, HCM studies with septal myectomy only, HCM studies without MV intervention, incomplete or suboptimal reporting of clinical and echocardiographic outcomes, non-HCM studies, case reports, and review articles.

Two authors (C.G.M., R.F.) reviewed and extracted the data from the studies. The baseline characteristics and demographics included number of patients, age, gender, clinical risk factors, New York Heart Association function class, medications, presence of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, and prior percutaneous septal alcohol ablation. Operative techniques used for the septal myectomy and edge-to-edge MV repair were reviewed and described. The echocardiographic variables analyzed included measures of LV size, function, and interventricular septal wall thickness, maximum LVOT gradient, and the presence of moderate or greater MR, SAM, or mitral valve apparatus abnormalities. The data extracted from the last available follow-up included operative death, cumulative survival, recurrence of moderate or greater MR, transmitral Doppler gradients, reoperation for recurrent MR, need for permanent pacemaker implantation, and persistence of New York Heart Association Functional Classification III or IV heart failure symptoms. The study quality and risk of publication bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias.

The systematic review was performed using Review Manager 5.3 software (Nordic

Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark). The results are presented as frequency and

percentage and mean

A total of 35 studies were identified, of which 6 met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed [17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]. The reasons for exclusion of the remaining 29 studies were: case reports of HCM with surgical or percutaneous MV edge-to-edge repair (N = 8), HCM studies without MV intervention (N = 7), HCM studies with MV intervention lacking data (N = 6), societal guideline documents (N = 3), review papers (N = 3), and non-HCM studies (N = 2). Of the 6 included studies, there was 1 randomized controlled trial in which participants underwent septal myectomy combined with either MV edge-to-edge repair versus secondary chordal cutting. The remaining 5 studies were retrospective analyses.

There were 158 patients included in the studies. The mean age was 51

| Study | N | Age | Female | Hypertension | Diabetes | NYHA Class III/IV | Beta-Blockers | Ca |

ICD | Prior EtOh Ablation |

| Jiang 2021 [17] | 51 | 47 |

22 (43%) | 23 (45%) | 5 (10%) | 16 (31%) | 35 (69%) | 13 (25%) | NA | NA |

| Afanasyev 2021 [18] | 24 | 51 |

10 (42%) | NA | NA | 24 (100%) | NA | NA | NA | 0 |

| Lapenna 2020 [19] | 26 | 59 |

6 (23%) | 7 (27%) | 2 (8%) | 13 (50%) | 16 (62%) | 11 (42%) | 3 (11%) | 0 |

| Obadia 2017 [20] | 22 | 49 |

9 (41%) | 3 (14%) | 4 (18%) | 12 (55%) | 20 (91%) | 3 (14%) | 5 (23%) | 2 (9%) |

| Collis 2017 [21] | 11 | 48 |

4 (36%) | NA | NA | 11 (100%) | NA | NA | NA | 0 |

| Shah 2016 [22] | 24 | 57 |

11 (46%) | NA | NA | 20 (83%) | NA | NA | NA | 0 |

| Total | 158 | 51 |

62/158 (39%) | 33/99 (33%) | 11/99 (11%) | 96/158 (61%) | 71/99 (71%) | 27/99 (27%) | 8/48 (17%) | 2/107 (2%) |

| EtOh,-Alcohol; N, Number; NYHA, New York Heart Association. | ||||||||||

The indication for septal myectomy was drug-refractory symptomatic LVOT obstruction in all participants. The indication for edge-to-edge repair was SAM plus moderate to severe MR in 2 studies, reduced septal thickness necessitating a limited septal myectomy with or without MV abnormalities in 2 studies, moderate or greater MR and a small LV cavity in 1 study, and SAM with or without MV abnormalities in 1 study. Additional MV pathology included an elongated anterior MV leaflet in 57 (36%) patients, and papillary muscle abnormalities in 13 (8%).

The Morrow procedure was used to perform the septal myectomy in all patients (Figs. 1,2,3, Ref. [25]) [23, 24, 25]. A classic technique was utilized in the 2 studies which included patients with reduced septal thickness necessitating a limited septal myectomy, and who had intrinsic MV abnormalities. This generally involves resection limited to the basal interventricular septum. In 4 studies, a modified technique was utilized in which the resection extends to the mid-ventricular level, from the interventricular septum distal to the anterior MV leaflet contact site. All edge-to-edge MV repairs were performed by suture approximation of the A2 and P2 scallops of the anterior and posterior leaflets, respectively (Fig. 4). A transaortic surgical approach was utilized in 3 studies, a transmitral approach was performed 2, and 1 study utilized both according to surgeon preference. In 4 (2%) patients with myxomatous MV disease and posterior leaflet prolapse, a 35-mm St. Jude Tailor annuloplasty ring was implanted for annular support (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA); the remaining repairs were completed without use of a ring.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Surgeon’s view of the interventricular septum and mitral valve via an aortotomy and transaortic approach. A transverse aortotomy exposes the aortic valve. The subaortic structures are visualized by using pericardial sutures on the right margin of the aortotomy to position the apex posteriorly, and inferior sutures to aid in retracting the aortic valve cusps. The mitral valve is seen near the 7 o’clock position and the interventricular septum near the 2 o’clock position. Reproduced with permission from reference [25].

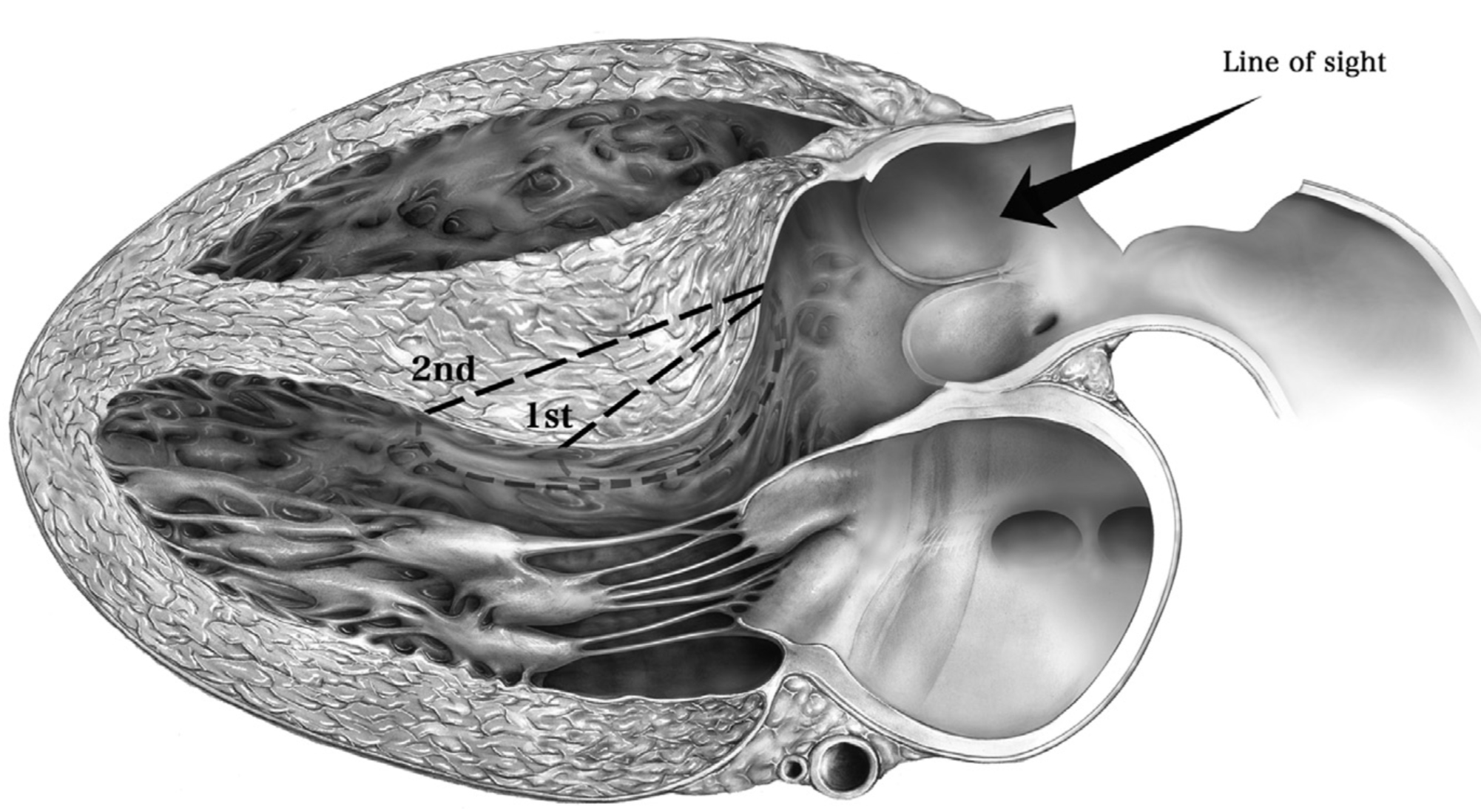

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Sagittal long-axis view of the left heart. Depicted is the viewpoint (‘line of sight’) through the aortotomy in a sagittal orientation of the hypertrophied basal interventricular septum. A classic Morrow procedure can be performed by resecting the marked 1st segment of interventricular septum, or extended distal to the mid-ventricular level to include the 2nd marked segment. Reproduced with permission from reference [25].

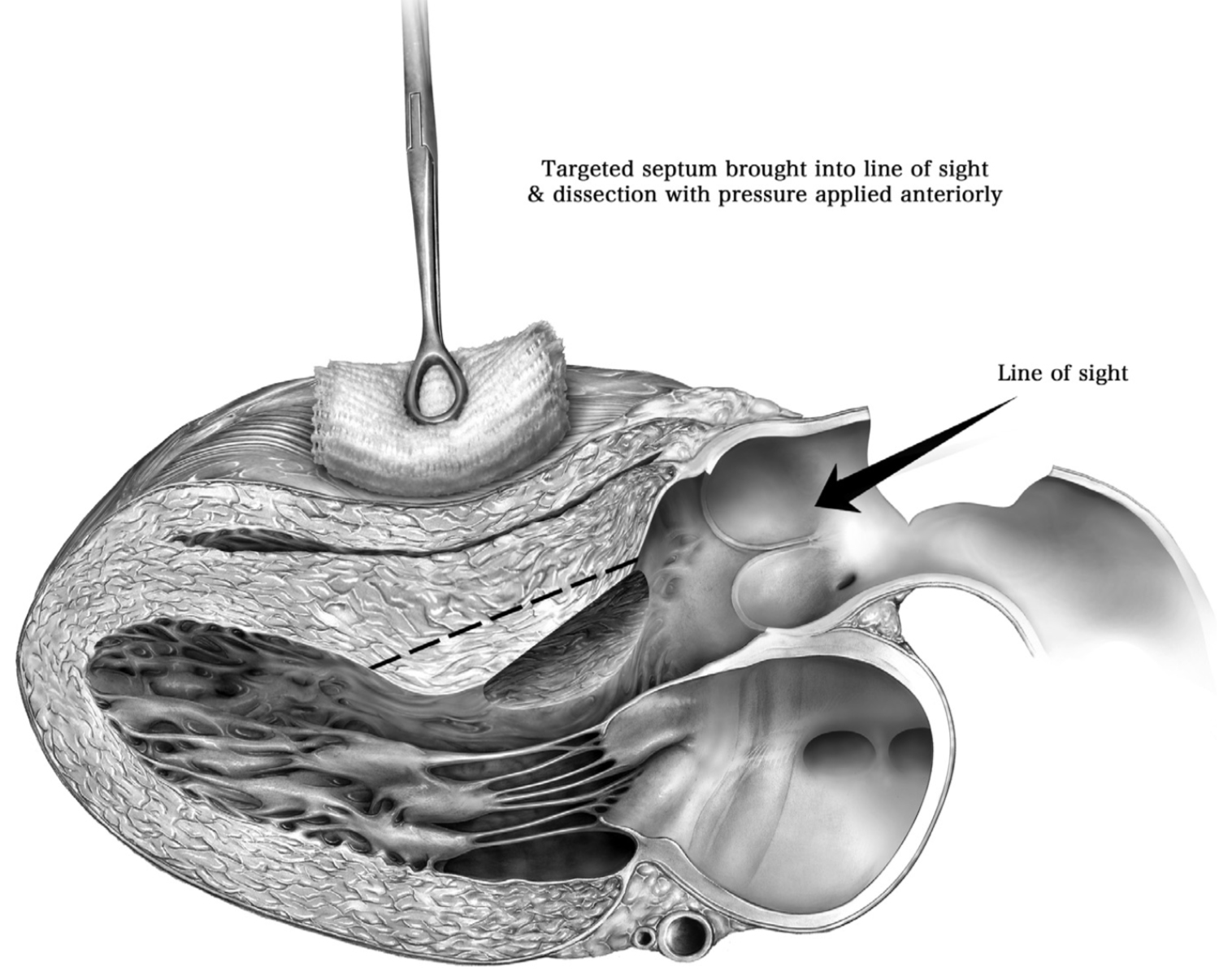

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Sagittal long-axis view of the left heart during septal myectomy. Depicted is the viewpoint (‘line of sight’) through the aortotomy in a sagittal orientation of the basal interventricular septum status post myectomy. As noted, the septum can be displaced into the surgical view by applying external anterior pressure, as needed. Reproduced with permission from reference [25].

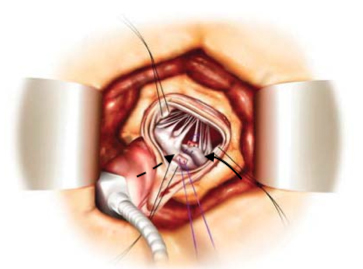

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Surgeon’s view of the mitral valve via an aortotomy and transaortic approach. The anterior and posterior mitral valve leaflets are visualized with the middle A2 and P2 scallops approximated and sutured together. Dashed black arrow, anterior mitral leaflet; solid black arrow, posterior mitral leaflet.

Additional procedures included 8 left atrial appendage ligations, 7 ablations

for atrial fibrillation, 4 aortic valve replacements, 1 coronary artery bypass

grafting, 1 subaortic membrane resection, and 1 tricuspid valve repair. The mean

cardiopulmonary bypass time was 79

The mean follow-up was 2.8

| Study | LV ejection fraction (%) | LVOT gradient (mmHg) | Interventricular septal thickness (cm) | LV internal diastolic diameter (cm) | Moderate or greater mitral regurgitation | Mitral valve systolic anterior motion |

| Jiang 2021 [17] | ||||||

| Preoperative | NA | 97 |

2.4 |

4.2 |

51 (100%) | 51 (100%) |

| Follow-up | NA | 19 |

1.5 |

4.4 |

0 | 0 |

| Afansayev 2021 [18] | ||||||

| Preoperative | 74 |

93 |

2.5 |

4.1 |

24 (100%) | 24 (100%) |

| Follow-up | 59 |

20 |

1.8 |

4.6 |

0 | 0 |

| Lapenna 2020 [19] | ||||||

| Preoperative | 62 |

63 |

NA | NA | 19 (73%) | 19 (73%) |

| Follow-up | 57 |

9 |

NA | NA | 6 (23%) | 0 |

| Obadia 2017 [20] | ||||||

| Preoperative | 71 |

75 |

2.6 |

4.1 |

11 (50%) | 22 (100%) |

| Follow-up | NA | 5 |

1.9 |

NA | 0 | 0 |

| Collis 2017 [21] | ||||||

| Preoperative | 72 |

60 |

1.8 |

4.6 |

NA | 11 (100%) |

| Follow-up | 64 |

21 |

1.6 |

4.5 |

NA | 0 |

| Shah 2016 [22] | ||||||

| Preoperative | NA | 78 |

NA | NA | 19 (89%) | 24 (100%) |

| Follow-up | NA | 19 |

NA | NA | 1 (4%) | NA |

| Totals | ||||||

| Preoperative | 69 |

82 |

2.4 |

4.2 |

124/147 (84%) | 151/158 (96%) |

| Follow-up | 59 |

16 |

1.7 |

4.4 |

7/146 (5%) | 0/133 |

| p |

p |

p |

p = 0.32 | p |

p | |

| LV, Left ventricle; LVOT, Left ventricular outflow tract; NA, Not available. | ||||||

Within the follow-up period there were 3 additional deaths resulting from congestive heart failure in 2 patients and sudden cardiac death in 1 patient, with a cohort survival rate of 97%. There were 3 (2%) re-operative MV replacements for recurrent severe MR: 1 patient with myxomatous MV disease that had persistent posterior leaflet prolapse, and 2 patients with abnormal papillary muscles resulting in residual LVOT obstruction and valve dysfunction. Finally, 4 (3%) patients remained in New York Heart Association functional class III/IV due to progressive heart failure and diastolic dysfunction, and 8 (6%) who required permanent pacemaker implantation (Table 3, Ref. [17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]).

| Study | Mortality | Permanent pacemaker implantation | NYHA functional class III/IV | Mean transmitral gradient (mmHg) | Mitral valve reoperation |

| Jiang 2021 [17] | 0 | 1 (2%) | NA | 3 |

0 |

| Afanasyev 2021 [18] | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 0 | 4 |

0 |

| Lapenna 2020 [19] | 3 (12%) | NA | 2 (8%) | 3 |

2 (8%) |

| Obadia 2017 [20] | 0 | 2 (9%) | 0 | 4 |

0 |

| Collis 2017 [21] | 0 | 1 (9%) | 2 (18%) | NA | 1 (9%) |

| Shah 2016 [22] | 1 (4%) | 3 (13%) | 0 | 5 |

0 |

| Total | 5/157 (3%) | 8/131 (6%) | 4/106 (4%) | 4 |

3/157 (2%) |

| NA, Not available; NYHA, New York Heart Association. | |||||

In the present systematic review of septal myectomy plus edge-to-edge MV repair for obstructive HCM, the following findings were observed at an early to mid-term follow-up of 2.8 years: (1) the classic or modified Morrow technique was performed for septal myectomy, and nearly all edge-to-edge MV repairs were completed without an annuloplasty ring; (2) there were significant reductions in the peak LVOT gradient, interventricular septal wall thickness, and moderate or greater MR, with elimination of SAM in all patients; (3) while there was a decrease in the LV ejection fraction, there was favorable chamber geometry as evidenced by a stable LV internal diastolic diameter; and, (4) clinical outcomes were quite satisfactory, with a survival rate of 97%, re-operative MV surgery in 2%, persistent New York Heart Association functional class III/IV heart failure symptoms in 3%, and permanent pacemaker implantations in 6%.

Septal myectomy using the classic Morrow technique was introduced in 1968 and

involves resection of the basal interventricular septum, which allows for an

increase in the LVOT diameter; however, there is risk of residual SAM due to

persistent abnormal flow vortices or MV apparatus geometry, particularly in

patients with more extensive hypertrophy [26, 27, 28]. In the modified Morrow

technique, the resection is extended to the mid-ventricular level distal to the

point of anterior MV leaflet-septal contact [24, 25]. This results in a larger

streamlined LVOT and avoidance of residual septal bulging, with improvement in

symptoms and a long-term survival commensurate to the age and sex-matched general

population [29]. Nevertheless, registry data has reported a variable risk of

persistent SAM or MR after myectomy alone, particularly in the presence of

intrinsic MV apparatus abnormalities [30, 31]. In a study by the Cleveland Clinic

group of 115 patients with HCM and MV disease, MV pathology included restrictive

leaflets (70%), elongated leaflets (56%), degenerative changes (31%),

myxomatous disease (20%), papillary muscle abnormalities (20%), and restrictive

chordae (19%) [32]. Over a third of the patients in the present study had

elongated anterior MV leaflets, and a small group had papillary muscle pathology.

Thus, the European Society of Cardiology recommendations for MV surgery in HCM

include: (1) symptomatic patients with an LVOT gradient

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Adult Cardiac Surgery Database cites a

34% incidence of concomitant MV surgery during myectomy for obstructive HCM in

the United States, of which 60% are repairs and 40% replacements [33]. It is

notable that concomitant myectomy and MV surgery is associated with a higher

morbidity and mortality when compared with myectomy alone (odds ratio [OR] 1.81,

95% Confidence Interval [CI] 1.39–2.36), with MV replacement conferring a

higher adjusted composite risk than repair (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.55–3.16 vs 1.61,

95% CI 1.18–2.18). When performing MV repair in the setting of septal myectomy

for obstructive HCM, utilization of the edge-to-edge technique offers several

advantages. It is a straightforward repair technique that is reproducible, and

adds a relatively small amount of time to the duration of cross-clamping and

cardiopulmonary bypass [10]. The A2 and P2 scallops of the MV are well seen

through the aortic valve orifice which avoids the necessity for an atriotomy, and

limits surgical dissection and trauma to the mitral valve [34]. The latter point

is salient, as a transmitral myectomy requires incision and dissection of the

anterior mitral leaflet to expose the interventricular septum and subvalvular

apparatus, which then requires surgical repair. Nevertheless, a transmitral

approach to myectomy followed by edge-to-edge repair can be applied if it is

preferred or indicated. The primary concerns regarding the use of the

edge-to-edge MV repair are lack of an annuloplasty ring in the majority of cases,

and the risk of functional mitral stenosis. In patients with preserved annular

anatomy and lack of dilatation (end-systolic diameter

Reported demographics from the STS of HCM patients who undergo septal myectomy and MV repair includes a median age of 58 years, 48% female, 67% New York Heart Association functional class III/IV symptoms, and a mean LV ejection fraction of 67% [33]. The current cohort of pooled patients appears representative of this population. In the STS database of 500 concomitant septal myectomy and MV repair operations, operative mortality was 2%, 5% required a permanent pacemaker, and 0.6% developed a ventricular septal [33]. In 67 patients with HCM and intrinsic MV disease at the Cleveland Clinic, operative mortality was 3%, freedom from moderate-to-severe recurrent MR at 1-year was 90%, and 1-year and 5-year survival were 91% and 81%, respectively [32]. Of note only 16% of patients received an annuloplasty ring as part of the MV repair, and 13% were treated with an edge-to-edge stitch in that report. Placed within the context of these data, the current study supports the edge-to-edge MV repair as a viable treatment option for carefully selected HCM patients undergoing septal myectomy and confers outcomes similar to historical and conventional series.

There are several limitations to consider when interpreting the current data. Firstly, 5 of the 6 included studies were retrospective in nature which confers an inherent selection bias. Additionally, the data are essentially observational due to the lack of a comparative control group. Secondly, the sample size was small which decreases statistical power, and not all of the measured variables were available uniformly across the studies. This latter point is important as it represents a form of attrition bias. Thirdly, a substantial number of patients had abnormalities of the MV apparatus in the form of anterior MV leaflet elongation or papillary muscle pathology, or underwent other surgical procedures in addition to septal myectomy and edge-to-edge MV repair. Furthermore, the operations were performed using transaortic access or through an atriotomy, with no specific details regarding outcomes based on the approach. The heterogeneity of the population in terms of pathology, as well as in the additional cardiac procedures performed in a small subgroup of patients, impacts the operative risk and is a form of performance bias. Finally, the follow-up was limited to approximately 3 years. Given the relatively young age of the population and typical clinical course of HCM, these results cannot be interpreted as representative of long-term outcomes.

In conclusion, combined septal myectomy and edge-to-edge MV repair is a safe and viable treatment strategy in the surgical management of HCM. The current data are best interpreted as supporting the effectiveness of this approach in carefully selected patients, with larger and longer-term studies warranted to assess clinical benefit and durability.

CGM, EE, and FN—study design; CGM, RF—data analysis; CGM, EE, RF—methodological assessment and results; CGM, EE, RF, FN—manuscript writing. All authors read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Christos G. Mihos and Francesco Nappi are serving as the Guest editors of this journal. We declare that Christos G. Mihos and Francesco Nappi had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Peter A. McCullough.