- Academic Editor

Acute gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) effects of alcohol consumption are well-known, whereas prior research has yielded inconsistent findings regarding on adaptations of the GABAergic neurotransmitter system to chronic alcohol use. Previous studies indicate either elevated or reduced GABA levels in cortical regions such as the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) in persons with alcohol use disorder (AUD). We tested the hypothesis that active alcohol consumption compared to abstinence contributes to GABA levels as observed in prior research on chronic alcohol use.

We investigated GABA levels in the ACC of 31 healthy controls (low risk, LR), 38 high risk individuals providing an active drinking pattern (high risk, HR) and 27 recently detoxified alcohol-dependent (AD) subjects via proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS).

GABA levels in the ACC were significantly lower in HR compared with AD, but did neither differ between LR and AD nor between LR and HR. Also, we observed a quadratic effect indicating a distribution of GABA levels in the ACC as follows: LR > HR < AD. GABA levels were not associated with abstinence duration in AD.

This study suggests that the GABAergic neurotransmitter system is blunted in AUD. More precisely GABA levels in the ACC seem to be higher in recently detoxified AD patients than in individuals at high risk which might suggest that GABA levels may increase after abstinence. No correlation was found between GABA levels and abstinence duration. Longitudinal studies are required to investigate alterations in the GABAergic system throughout the development and maintenance of AUD.

No: NCT02094196. Registered 20 March 2014, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02094196.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a mental condition associated with premature death and disability worldwide [1]. It can manifest as a chronic relapsing disorder with severe mental and physical consequences for the individual as well as their friends and families [1]. The pathogenesis of AUD is not yet completely understood, and different neurotransmitter systems have been implicated during the development and maintenance of the disease. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system [2] and GABA receptors are activated by acute alcohol consumption leading to pleasurable behavioral effects such as anxiolysis and sedation. The GABAergic neurotransmitter system appears to be dysfunctional in AUD, although the precise mechanisms remain unclear [3, 4, 5]. Several studies have reported decreased GABA concentration within the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) of individuals with AUD relative to healthy controls (HC) [6, 7]. In contrast, other studies did not find differences of GABA levels between HC and persons with AUD in the ACC [8, 9]. Taken together, the authors reviewing these studies conclude that GABA seems to be increased or decreased before initiating abstinence, then decreased during early abstinence and increase or normalize again during prolonged abstinence [3]. GABAergic neurotransmission significantly influences the dopaminergic system [10], underscoring the role of GABA in modulating reward pathways, a key factor in the etiology of AUD. Our research group recently identified a negative correlation between GABA concentration in the ACC and dopamine D2/3 receptor availability within the associative striatum in healthy control subjects. This relationship was not observed in individuals at high risk for or recently detoxified from alcohol-dependent (AD) [11]. This potential regulatory cortical mechanism of the mesolimbic reward system appears to be disrupted in AUD, suggesting a complex interaction of multiple neurotransmitter systems in the development and maintenance of the condition.

This study aimed to investigate GABA levels in the ACC of healthy controls (low risk, LR), actively drinking individuals at high risk (HR) for alcohol dependence, and recently abstinent alcohol-dependent (AD) patients. Based on previous research, we hypothesized that GABA levels would be decreased in HR individuals compared to LR. Additionally, we hypothesized an increase in GABA levels in AD patients relative to HR individuals. Furthermore, we explored the correlation between abstinence duration and GABA levels in the ACC of AD patients.

The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin; EA1/245/11), and all patients or their families/legal guardians gave written consent before participating in the study. A subsample of this proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) data has already been published together with 18F-fallypride positron emission tomography (PET) data [11]. This study was a component of a large, multi-site study examining the neurobiological and cognitive alterations associated with the onset and persistence of AUD (LeAD study; Project 5, The Role of Dopaminergic and Glutamatergic Neurotransmission for Dysfunctional Learning in Alcohol Use Disorders, https://gepris.dfg.de/gepris/projekt/209293518, clinical trial number: NCT02094196).

The study sample consisted of 96 participants divided into three groups: 31 LR individuals, 38 HR individuals, and 27 recently detoxified AD patients. The three groups were comparable in terms of age, handedness, and smoking status (see Table 1 (Ref. [12, 13, 14]) for detailed demographic information). Although we tried to match groups carefully, there was a trend towards a significant difference in the smoking status between groups which is why we included smoking as a covariate in our analyses. LR control participants were recruited from the general population, while AD patients were enrolled from various inpatient psychiatric clinics in Berlin. HR individuals were also recruited from the community and classified as such based on an Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) score exceeding eight [15]. To ensure diagnostic accuracy, all participants underwent a Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) to exclude alcohol dependence according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition (DSM-IV) criteria in HR and LR groups and to rule out any history of other substance use disorders [16, 17].

| Group (N = 96) | ANOVA | ||||

| Demographic Variables | LR (n = 31) | HR (n = 38) | AD (n = 27) | F/p value | |

| Gender | 6 female, 25 male | 4 female, 34 male | 5 female, 22 male | 0.018/0.893 | |

| Handedness | 31 right-handed | 31 right-handed | 26 right, 1 left-handed | 1.32/0.271 | |

| Smokers, % | 71% | 95% | 89% | 3.92/0.051 | |

| Mean (SD) | |||||

| Age, years | 46.3 (9.8) | 43.1 (9.0) | 45.6 (10.3) | 2.47/0.332 | |

| Education, years | 14.5 (2.8) | 16.3 (4.1) | 15.2 (3.6) | 0.831/0.672 | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Duration of abstinence, days | - | - | 36.2 (20.1) | - | |

| Symptom severitya | 3.0 (3.9) | 7.8 (6.8) | 16.4 (6.2) | 4.68/ | |

| Cravinga | 2.8 (3.2) | 8.2 (5.3) | 13.7 (8.3) | 4.08/ | |

| Anxietya | 2.5 (2.3) | 7.5 (3.3) | 5.3 (3.6) | 1.74/0.093 | |

| Depressive symptomsa | 2.2 (2.6) | 5 (3.2) | 3.3 (3.2) | 0.90/0.537 | |

| Age at first drink | 14.9 (1.9) | - | 14.3 (3.7) | - | |

| Age of first AD diagnosis | - | - | 32.1 (11.8) | - | |

| Years since AD diagnosis | - | - | 12.7 (9.5) | - | |

aSymptom severity of alcohol-related symptoms measured via ADS Score [12], Craving symptoms measured via OCDS [13], Anxiety symptoms measured via HADS-A [14], Depressive symptoms measured via HADS-D [14]. *Significant difference. AD, alcohol-dependent; ANOVA, analysis of variance; LR, low risk; HR, high risk; SD, standard deviation; ADS, Alcohol Dependence Scale; OCDS, Obsessive-Compulsive Drinking Scale; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - Anxiety symptoms; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - Depressive symptoms.

All AD patients completed an inpatient detoxification program prior to study

enrollment. Participants were diagnosed with AD according to both the

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health

Problems 10th revision (ICD-10) and DSM-IV criteria by a qualified clinician and

had a minimum of three years of AD history. To minimize pharmacological

influences, AD subjects were medication-free for at least four half-lives of any

previously prescribed psychotropic drug and exhibited mild withdrawal symptoms

(Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) - Score

MRI data were acquired using a 3 Tesla Verio scanner (Siemens Healthcare,

Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a 32-channel receive-only head coil. Following a

localization scan, high-resolution anatomical images were obtained using a

three-dimensional T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition with

gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence. Image acquisition parameters included a

repetition time (TR) of 2.3 ms, an echo time (TE) of 3.03 ms, a flip angle of

9°, a 256

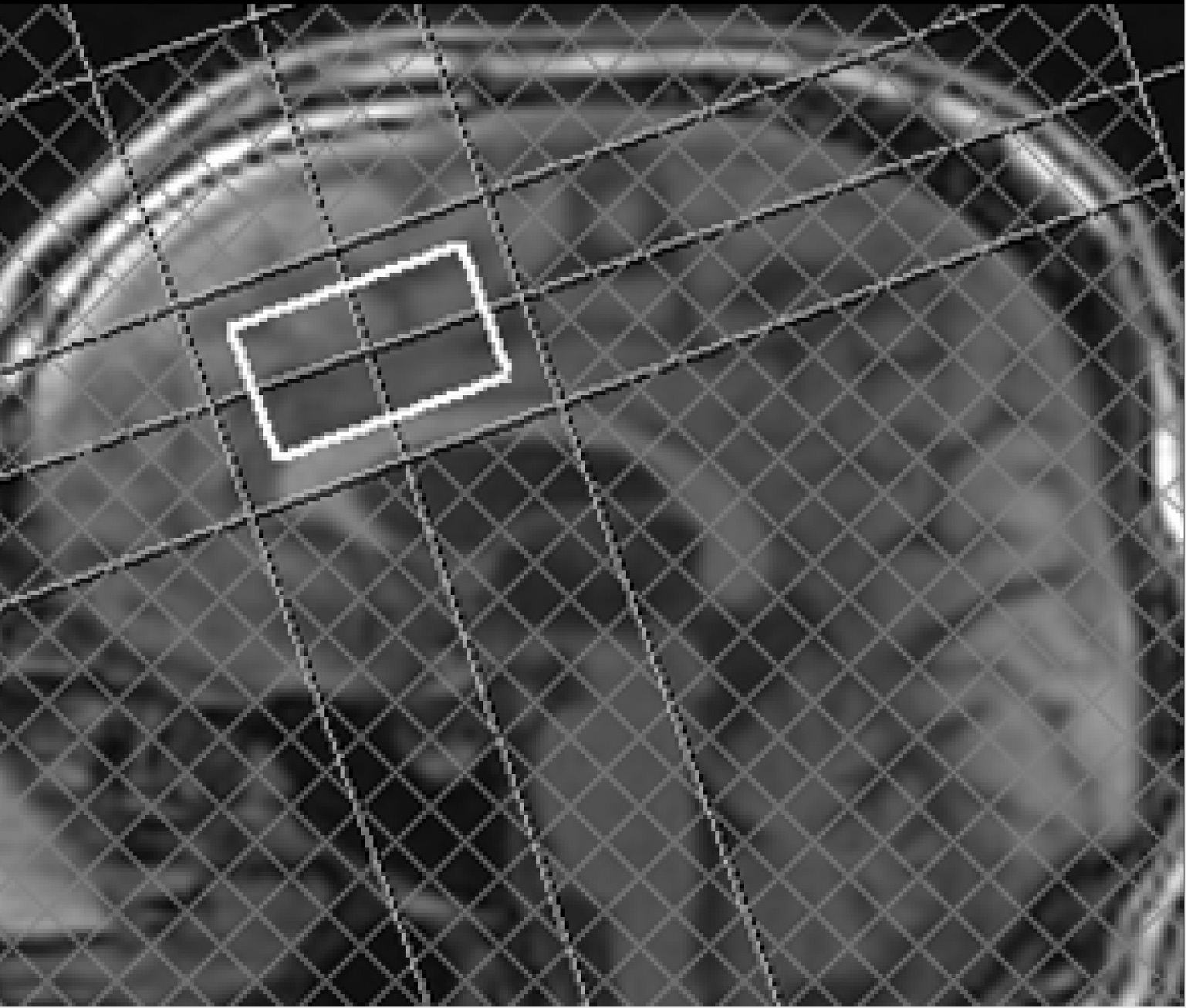

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) voxel

position of the voxel of interest in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) with a

voxel size of 25

Statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Statistics Version 29.0.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). From the total sample size of 96 subjects GABA levels in the ACC were available for 92 subjects. Further, outliers were visually identified and consecutively excluded. We excluded two outliers in the LR, one in the HR and one in the AD group with a resulting sample size of 88 (LR = 28, HR = 35, AD = 25). After the exclusion of outliers’ normal distribution was achieved and statistically confirmed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test.

We included smoking status as a covariate into the analyses as it has been shown

that smoking seems to influence cortical GABA levels in HC as well as AD [28] and

our groups differed marginally significant in their smoking status (see

descriptive statistics, Table 1). We performed the group comparison of GABA

levels in the ACC with an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and consecutive post

hoc tests. To analyze the relationship between the alcohol use pattern and GABA

levels, planned contrast weights were investigated for a (negative) quadratic (LR

There was a significant effect of group (LR/HR/AD) on GABA levels in the ACC

F(2, 84) = 4.08, p = 0.020. Further, we observed a significant quadratic

trend F(2, 85) = 4.99, p = 0.030 throughout the sample, indicating a

distribution of GABA levels as follows: LR

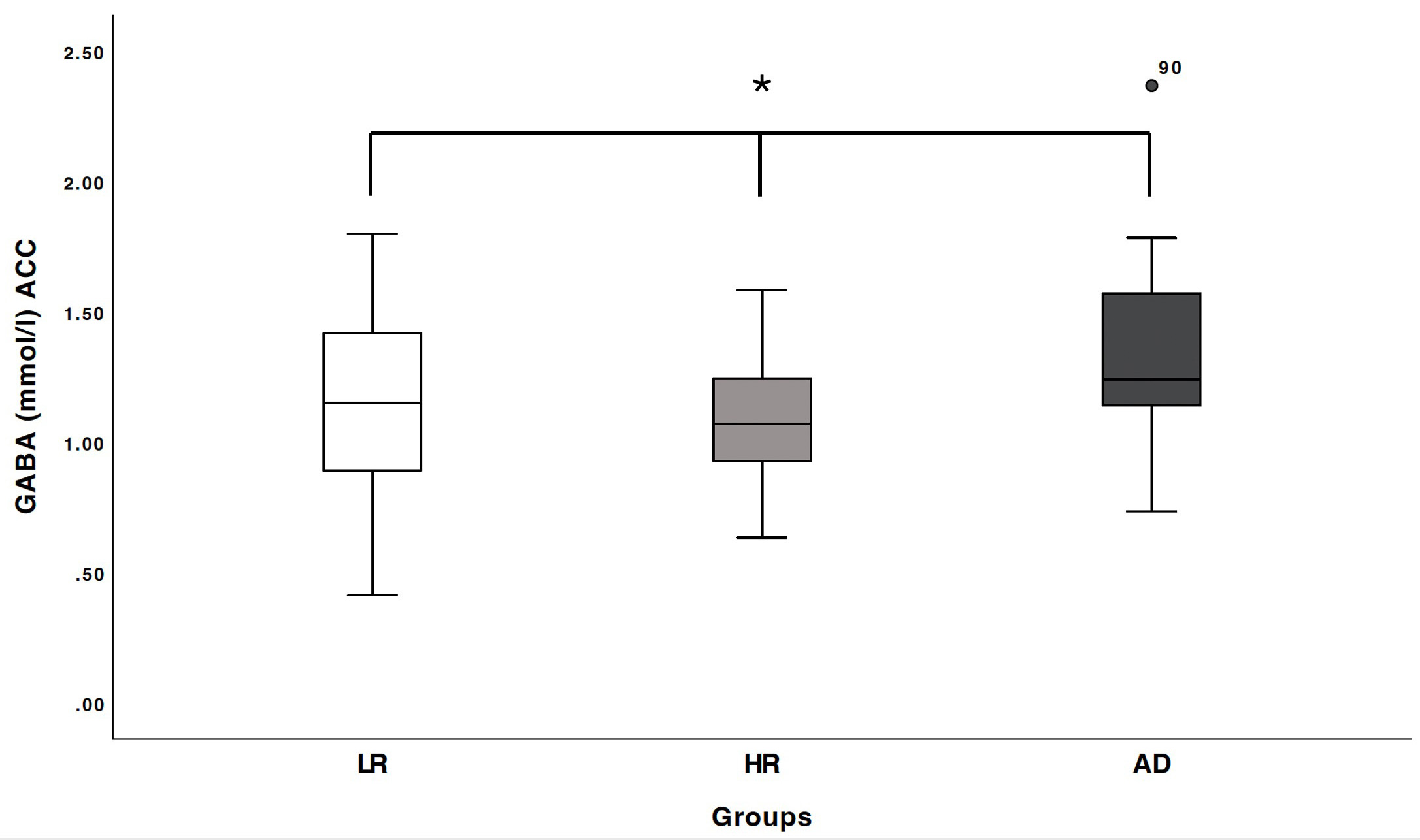

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Boxplots of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) concentration (in

mmol/L) within the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) were generated for three

groups: low-risk healthy controls (LR), individuals at high risk of alcohol use

disorder (HR), and recently detoxified alcohol-dependent patients (AD). *a

significant group difference was observed (F(2,85) = 4.14, p = 0.019),

as well as a significant quadratic trend (F(2,85) = 4.99, p = 0.028),

indicating a GABA concentration distribution of LR

Abstinence duration in AD (mean: 36.2 days, minimum: 8 days, maximum: 95 days, standard deviation: 20.1) was not correlated with GABA levels in the ACC Pearson correlation: r = –0.165, p = 0.431. Furthermore, GABA levels in the ACC were not correlated with craving symptoms (OCDS), symptom severity of alcoholism (ADS), depressive or anxiety symptoms (HADS) across the entire sample or within either the HR or AD groups.

GABA concentrations within the ACC were significantly elevated in recently

detoxified AD patients compared to high-risk individuals, consistent with our

initial hypothesis. However, no significant difference in GABA levels was

observed between AD patients and LR individuals. Furthermore, a significant

negative quadratic trend in GABA levels across the entire sample was identified,

suggesting a distribution pattern of GABA concentrations as follows: LR

Our findings are in line with the literature indicating that in actively

drinking individuals and in early abstinence the GABA levels seem to be decreased

compared to healthy controls [6, 29]. Although GABA levels were not significantly

reduced in HR compared to LR subjects, the significant quadratic effect (LR

As the GABAergic system seems to modulate the dopaminergic neurotransmitter system, it may interplay with the reward system that plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of additive disorders [10]. More specifically, potential cortical regulatory mechanisms exerted by GABA on mesolimbic dopamine function may be disrupted in AUD. This hypothesis is supported by our recent findings of a negative correlation between GABA levels in the ACC and dopamine D2/3 receptor availability within the dorsal striatum in healthy controls, a relationship absent in both high-risk individuals and recently detoxified AD patients [11].

Clinical implications of the modulated GABAergic neurotransmitter system may be deduced from the effective use of baclofen to improve abstinence in AUD [30, 31, 32]. Baclofen is a derivate of GABA which seems to activate GABA receptors and baclofen seems to reduce the total alcohol consumption although long-term effects are questionable [31]. In this study, we were not able to find an association of clinical variables with GABA levels in AD, and abstinence duration was not correlated with GABA levels in the ACC of AD subjects. This may be due to the three subgroups and the resulting relatively small sample size of this subgroup (n = 25).

In general, limitations of this study are the relatively small sample size of the subgroups due to the study design with three subgroups representing different stages of AUD. We accepted this limitation due to the dimensional approach of this study. Also, although effects of smoking on GABA levels were observed, groups trended towards a significant difference in smoking status which was subsequently included as a covariate. Another limitation is the informative value of 1H-MRS in general, as the total level of a neurotransmitter is calculated in the voxel of interest, but it is not clear whether the neurotransmitter is located pre- or postsynaptic and therefore the functional relevance is to somewhat degree restricted.

GABA concentrations within the ACC were significantly elevated in abstinent AD

subjects compared to those with an active drinking pattern. This observation

suggests a potential recovery of GABA levels towards the levels observed in LR

controls (low risk use, healthy controls) following a prolonged abstinence period

(mean: 36.2 days, approximately five weeks). This interpretation is supported by

our finding of a quadratic trend (LR

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

JG, AH, and FS were responsible for the study concept and design. GS, TG, AR and LMM analyzed the data and wrote the draft. GS, FS and SA further designed the experimental procedures and collected the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin; EA1/245/11) and all patients or their families/legal guardians gave written consent before participating in the study.

We thank Ralf Mekle for providing the SPECIAL sequence.

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Grant/Award Numbers: GA 707/6-1, HE 2597/14-1, HE 2597/14-2, HE 2597/15-1, HE 2597/15-2, RA 1047/2-1, RA 1047/2-2, SFB TRR 265.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.