- Academic Editor

†These authors contributed equally.

The incidence of endometriosis-associated malignancies (EAMs) is approximately 1%, with the majority occurring in the ovaries. This condition is often referred to as endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer (EAOC). However, the EAMs are rarer occurrences at other sites, such as the rectovaginal septum, abdominal wall, or perineal incision.

This case involves a 51-year-old female hospitalized at Zhuhai Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Hospital with abdominal pain and constipation. Colonoscopy revealed a rectal mass, and histopathological analysis indicated adenocarcinoma, suggesting endometrial cancer metastasis. However, following total laparoscopic hysterectomy, rectal resection, and lymph node dissection, pathological examination confirmed a final diagnosis of rectal endometriosis-associated malignancy (EAM) combined with endometrial cancer. Following surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, the patient remained disease-free during a 2-year follow-up period.

This case is rare and noteworthy, involving EAMs of the rectum combined with EC. Surgical intervention followed by adjuvant treatment could improve survival outcomes. Therefore, an accurate diagnosis is critical for effective management.

Endometriosis is a benign disease, yet it exhibits biological characteristics of malignant tumors, including proliferation, infiltration, diffusion, recurrence, and even metastasis [1]. Although endometriosis-associated malignancies (EAMs) are rare, they occur in approximately 0.7%–1% of cases, with the ovary being the most common site for endometriosis and its malignant transformation, which accounts for 76% of the cases [2]. The rectum and sigmoid colon are common sites of endometriosis-associated intestinal tumors (EAITs) primarily presenting as adenocarcinoma [3].

Distinguishing adenocarcinoma caused by an endometriosis-associated malignancy (EAM) from primary intestinal adenocarcinoma is challenging, particularly when the malignant transformation of rectal endometriosis is combined with endometrial cancer (EC), posing challenges for clinical and pathological diagnosis [3]. The management of rectal EAM, primary rectal cancer, and rectal metastasis from EC is critical to determining prognosis. In this case report, a case of rectal and fallopian tube EAM combined with EC has been presented. Additionally, we have identified the differential diagnosis of EAITs (rectum and sigmoid colon), primary rectal adenocarcinoma, and endometrial cancer with rectal metastasis through comprehensive histopathological examination. This accurate identification enables clinical doctors to develop clear diagnoses and guide subsequent treatment plans.

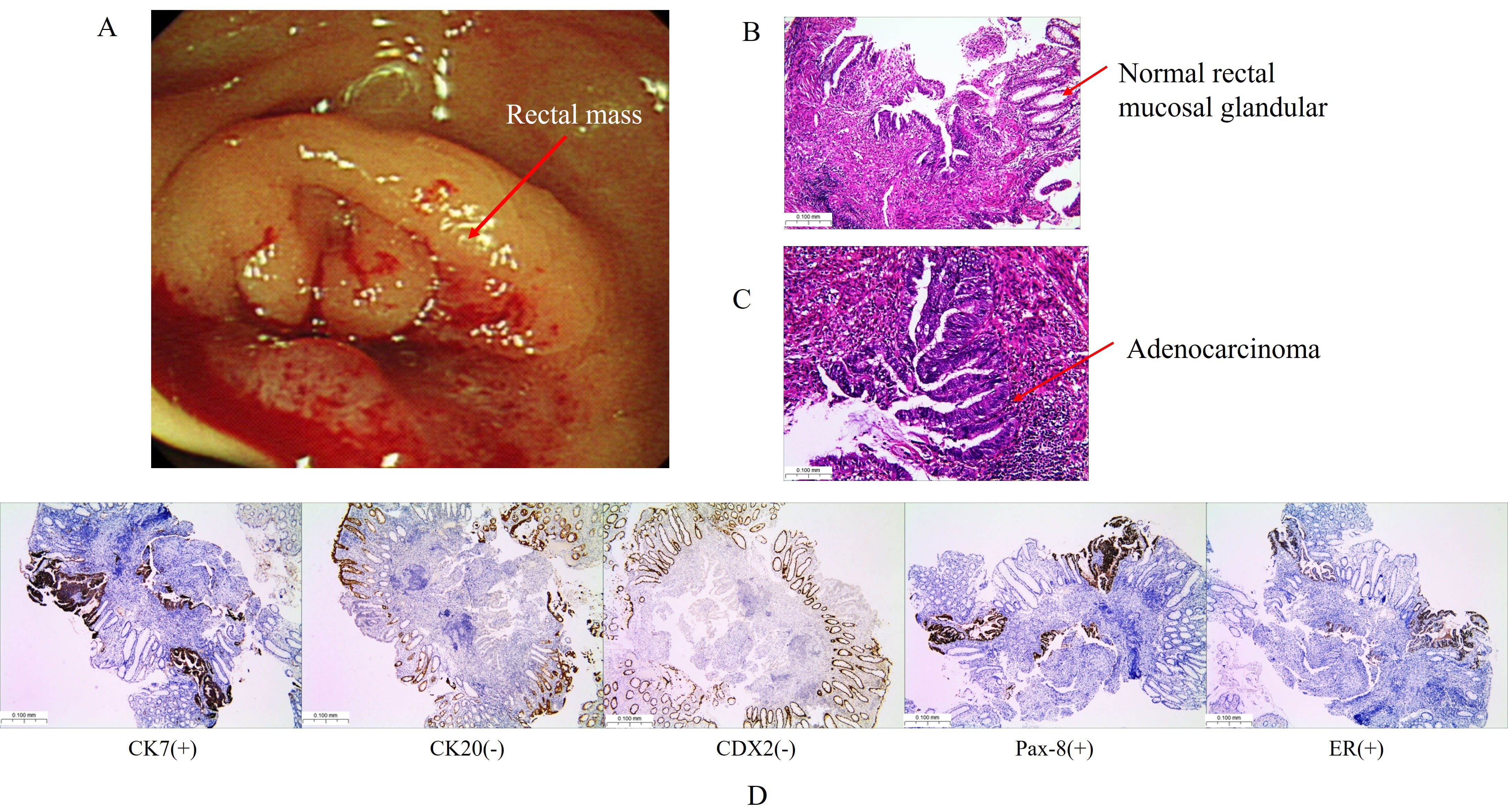

A 51-year-old female presented with abdominal pain and difficulty in defecation persisting for over 2 weeks. Her menstrual cycles were regular, and had one prior vaginal delivery. She had no significant past medical history (e.g., diabetes, hypertension) and no family history of cancer or inherited disorders. She was admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology at Zhuhai Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine. Enteroscopy CF-H260AZI (Olympus Corporation, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) revealed at 6 cm from the anal verge, a circumferential mass with dam-like intraluminal protrusion was observed. The lesion demonstrated irregular topography with ill-defined margins and ulcerated surfaces, exhibiting marked tissue friability manifesting as contact bleeding. Significant luminal stenosis (endoscope CF-H260AZI non-passable) was noted (Fig. 1A). Endoscopic evaluation reveals a transmural rectal mass demonstrating mucosal-to-serosal progression. Six targeted biopsies were obtained from the lesion and pathological examination confirmed adenocarcinoma, potentially representing metastasis from EC (Fig. 1B–D).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Colonoscopy and pathology findings. (A) Colonoscopy reveals a circular mass (red arrow) in the rectum, located 6 cm from the anus. (B) Hematoxylin-eosinstaining (H&E) demonstrating normal colonic mucosal glands and disorganized glandular configuration, the disorganized glandular configuration continues down to the muscularis mucosae (red arrow). (C) H&E staining confirms moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with infiltrative glands (red arrow). (D) Immunohistochemistry showed cytokeratin (CK) 7 (+), CK20 (–), caudal type homeobox (CDX) 2 (–), paired box gene 8 (Pax-8) (+), estrogen receptor (ER) (+). Scale bar = 100 μm

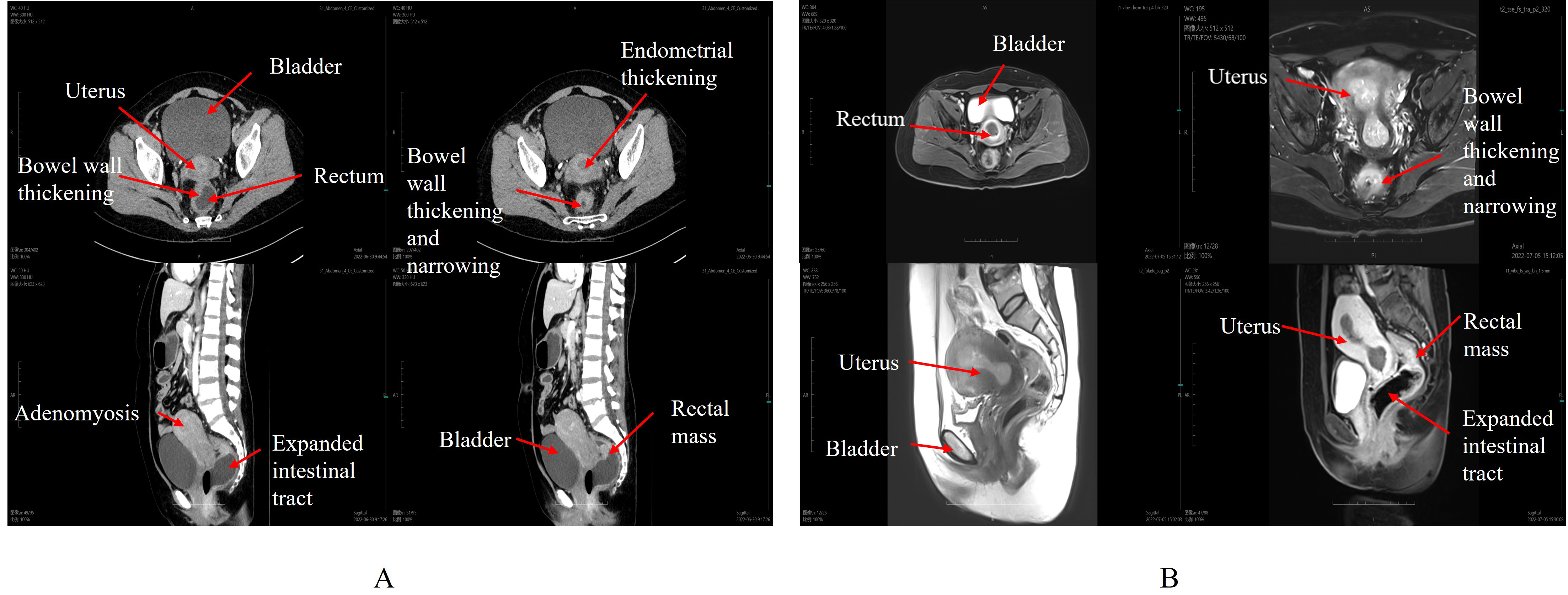

Full abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast revealed (Fig. 2A): a

mass at the rectosigmoid junction; a mass measuring approximately 58 mm

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Full abdominal computed tomography (CT) and pelvic cavity magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). (A) CT Imaging. (B) MRI Imaging. The CT and MRI demonstrate increased uterine volume with a spherical shape and asymmetry of the anterior and posterior walls. The heterogeneous endometrial thickening measuring 24.6 mm. Additionally, there is a thickening of the rectal and intestinal tracts, along with dilation of the sigmoid colon. The red arrow represents the organ part, and explanations are provided next to the red arrow (in white font).

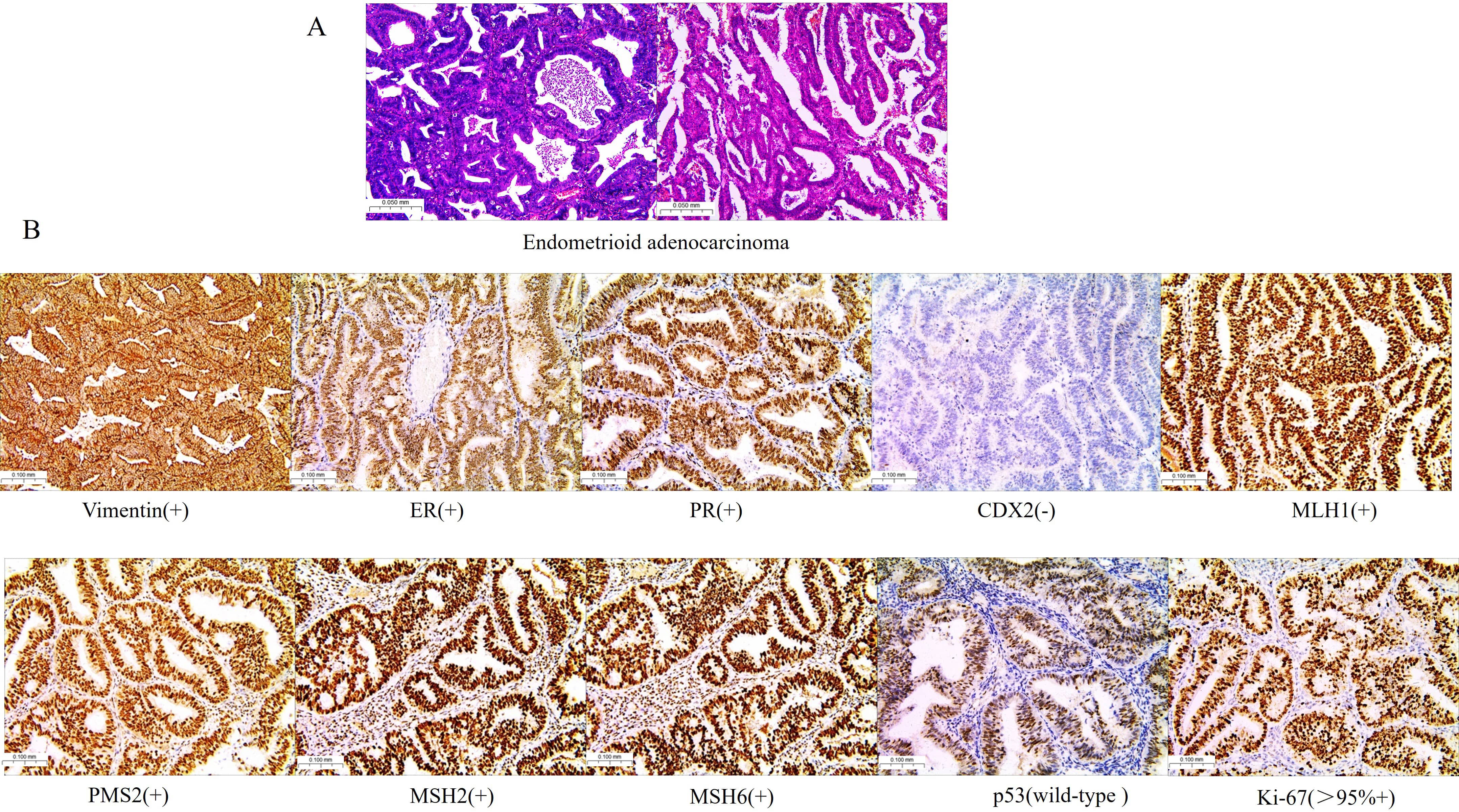

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Pathological and immunohistochemical in endometrial tissues. (A) H&E staining revealed endometrioid adenocarcinoma. (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of Vimentin, ER, progesterone receptor (PR), CDX2, MutL homologue 1 (MLH1), postmeiotic segregation increased 2 (PMS2), MutS homologue 2 (MSH2), MSH6, tumor protein 53 (p53), and marker protein Ki-67 in endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Scale bar = 100 μm

Based on CT, MRI, and pathological findings, the patient underwent surgery,

which included: total laparoscopic hysterectomy, bilateral oophorectomy, double

salpingectomy, pelvic lymph node dissection using indocyanine green tracking,

para-aortic lymph node dissection, rectal resection, mesenteric lymph node

dissection, and sigmoid colon rectal anastomosis. During intraoperative

exploration, the anatomical relationship between the rectal serosa and the

posterior wall of the uterus remains unclear. It is worth noting that there seem

to be some purple blue nodules visible in the pelvic floor, but they cannot be

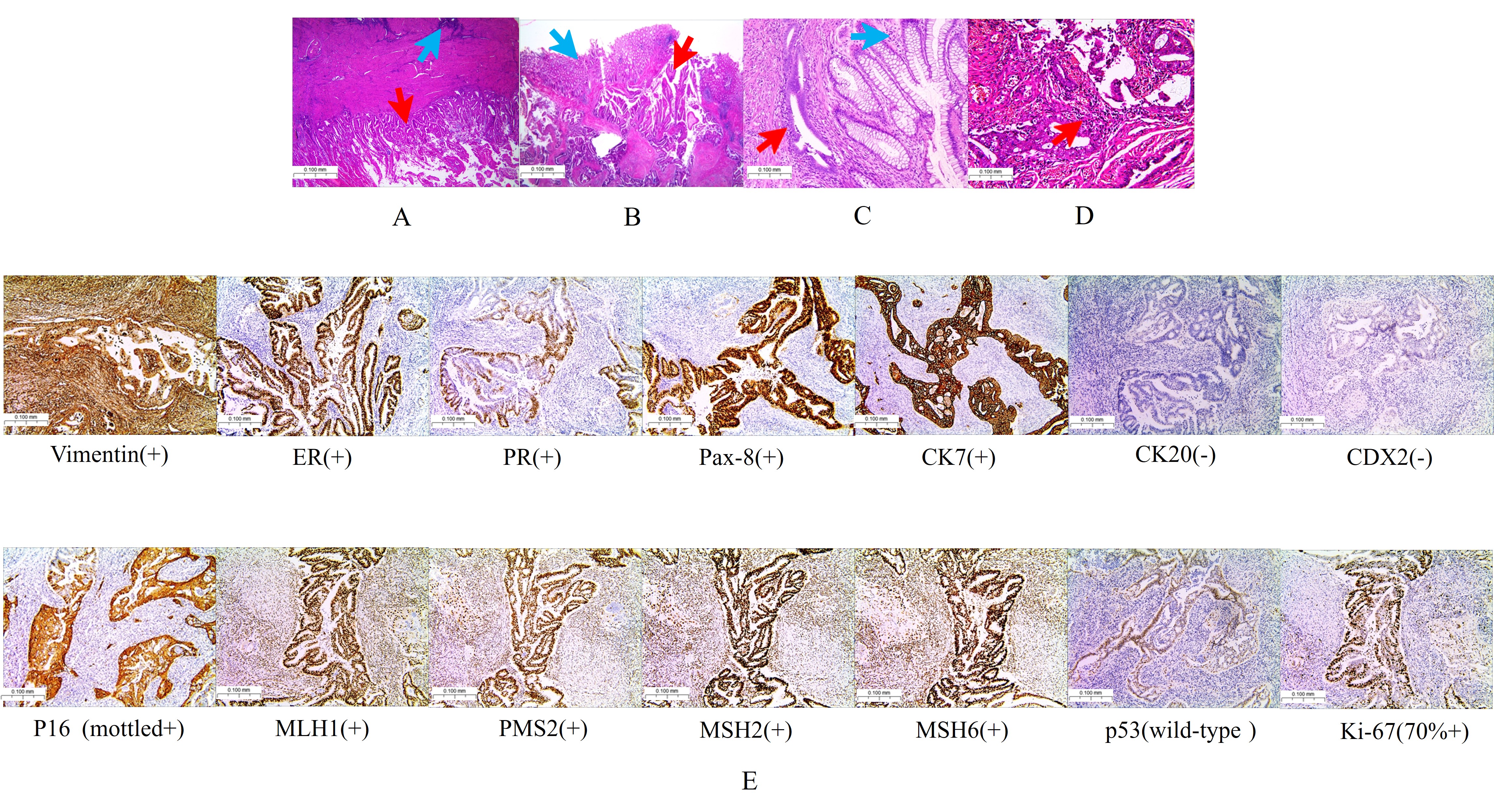

determined. The final post-surgical pathology revealed the following (Fig. 4A–D): Uterus: Highly differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous

cell metaplasia (FIGO stage I); tumor confined to the endometrium with focal

infiltration into the superficial muscle layer (

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Pathology and immunohistochemistry. (A) Endometrium: Endometrioid adenocarcinoma exhibiting focal infiltration into the superficial muscle layer (the red arrow represents endometrioid adenocarcinoma, and the blue arrow represents adenomyosis). (B) Rectal lesions (the red arrow represents endometrioid adenocarcinoma, and the blue arrow represents normal intestinal mucosa). (C) Endometriosis of the rectum (the red arrow represents endometriosis, and the blue arrow represents normal intestinal mucosa). (D) Endometrioid adenocarcinoma identified in the left fallopian tube (the red arrow). (E) Immunohistochemical markers (rectal lesions): Vimentin (+), ER (+), PR (+), Pax-8 (+), CK7 (+), CK20 (–), CDX2 (–), P16 (+), MLH1 (+), PMS2 (+), MSH2 (+), MSH6 (+), p53 (wild-type), Ki-67 (70% +). Scale bar = 100 μm

Based on postoperative and pathological findings, the rectal lesions were determined to be endometriosis with malignant transformation, rather than EC metastasis. Notably, gynecologists attribute the left tubal malignancy to metastasis from extra-tubal malignant transformation of endometriosis. The patient underwent six courses of chemotherapy (carboplatin combined with paclitaxel) and 25 sessions of radiotherapy. After 2 years of follow-up, the patient recovered without recurrence.

In this case, clarifying the diagnosis was crucial for guiding treatment and

improving prognosis. EC commonly occurs in women around menopause and

postmenopausal women, with peak incidence between ages 50 and 54 [4].

Approximately 70% of EC cases are detected when the tumour is confined to the

uterine body, considered early-stage and generally associated with a favourable

prognosis [5, 6]. However, 10% to 20% of patients with EC present with distant

metastasis, and their 5-year survival rate is

In this case, the pathology of the EC revealed that the lesion infiltrated only the superficial muscle layer, with no evidence of lymphovascular invasion or lymph node metastasis, and the tumor was ER and PR positive. This classifies the EC as Type I, FIGO 2009 stage IA2. Given the characteristics of EC metastasis, metastasis to the rectum and fallopian tubes was not considered in this case. In this case, the endometrial carcinoma demonstrated positive expression of ER, PR, and mismatch repair proteins, with somatic gene mutations detected in both tumor tissue and peripheral blood, including phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) p.R38H, PIK3CAp.Y1021C, Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homologue p.G12V, phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) p.R130Q, PTENp.K13, AT-rich interaction domain 1A p.Q1499Hfs*7, and neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homologue p.G12V, with no pathogenic or potentially pathogenic germline mutations. The molecular classification of the EC was determined to be a non-specific molecular profile.

The origin of the malignant tumor in the left fallopian tube remains uncertain. The gynecologists’ perspective—that it represents malignant transformation and metastasis from endometriosis—is based on two key observations: (1) hysteroscopy revealed no visible lesions at the left tubal ostium, and (2) the primary endometrial cancer was staged as FIGO 2009 stage IA2. They interpret the absence of visible tubal ostium involvement as evidence against direct extension from the endometrial primary. However, this view may not fully account for the established biological behavior of endometrial cancer, where direct tubal invasion can occur even in Stage I disease. Crucially, pathological examination of the left fallopian tube tissue revealed no evidence of underlying benign endometriosis. Based on the pathological findings and the recognized potential for occult tubal involvement by endometrial carcinoma, we favor the interpretation that the left tubal malignancy most likely represents metastatic spread from the primary endometrial cancer.

In primary intestinal adenocarcinoma, 75% to 95% of cases are CK7-negative and CDX2- and CK20-positive. However, 80% to 100% of endometrioid adenocarcinomas express CK7 positivity, with CK20 and CDX2 negativity [11, 12, 13]. In this case, CDX2 and CK20 were negative, while ER, PR, and CK7 were positive. More importantly, endometriosis lesions were found in the patient’s rectal tissue. Therefore, the rectal malignancy was not primary. Given the patient’s history of adenomyosis, the rectal lesion was ultimately diagnosed as EAITs.

EAMs are exceedingly rare, particularly those occurring outside the ovaries [14]. Therefore, there is no standardised treatment protocol for postoperative EAMs management [15]. The treatment of endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer (EAOC) should adhere to the principles of ovarian cancer management, including platinum-based chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy [16]. The efficacy and selection of EAMs chemotherapy agents remain inconclusive, although paclitaxel combined with carboplatin is considered a viable option for patients with EAMs outside of ovarian cancer [17]. Many researchers suggest that localised pelvic EAMs might benefit from adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy [15, 17]. In this case, the patient underwent chemotherapy and radiotherapy, with no recurrence after 2 years of follow-up.

This case is rare and noteworthy, involving EAMs of the rectum combined with EC. Surgical intervention followed by adjuvant treatment could improve survival outcomes. Therefore, an accurate diagnosis is critical for effective management. Although endometriosis is increasingly being diagnosed in young people, caution should be exercised towards EAM (especially EAOC) in perimenopausal women. Therefore, it is recommended to conduct regular follow-up evaluations every 3–6 months for patients with endometriosis during perimenopause.

All data used in this study can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author via e-mail at 739367458@qq.com.

YB, DZ, and WH: Wrote the original draft, methodology, and performed analyses. SF, CC, and HC: Collect clinical data and immunohistochemistry. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the patient provided written informed consent and agreed to publish it, and the Ethics Committee of Zhuhai Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine approved the study (approval number: 20240113006 and 2025-LW-006-E01).

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/CEOG39232.

During the preparation of this work the authors used DeepSeek in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.