- Academic Editors

†These authors contributed equally.

Premature rupture of the membranes (PROM) occurring after the 37th week of gestation, prior to the onset of regular contractions, affects approximately 8% of pregnancies and typically leads to the spontaneous onset of labor. A prolonged interval between PROM and delivery increases the risk of maternal infection and early neonatal sepsis. This prospective, randomized study aimed to assess the efficacy, safety, and maternal satisfaction associated with the use of a vaginal prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) delivery system compared to expectant management approach following PROM.

Term pregnant women with a singleton cephalic presentation, who experienced PROM within 4–12 hours and had an unripe cervix, were randomized into 2 groups. The intervention group received labor induction using a slow-release 10 mg dinoprostone (PGE2) vaginal delivery system, whereas the control group underwent expectant management. If active labor had not commenced within 24 hours of enrollment, labor was induced with oxytocin in both groups.

In this prospective randomized study, 74 pregnant women with PROM after the 37th week of gestation, prior to before the onset of active labor, were enrolled. Active labor began within 24 hours after enrollment in 54% of the control group and 77% of the intervention group (p = 0.036). The intervention group had a 3.42-hour shorter interval from randomization to delivery; however, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.067). When analyzing time to spontaneous vaginal delivery, administration of PGE2 in the intervention group was associated with a 4.3-hour reduction in delivery time (p = 0.029). There was no statistically significant difference regarding mode of delivery between the groups, with 6% of cesarean section in the intervention group vs. 15% in the control group (p = 0.343). No significant differences were observed between the groups in oxytocin use, labor complication rates, neonatal outcomes, or participant satisfaction. Notably, in a significant proportion of participants (37%) in the intervention group, the vaginal PGE2 delivery system was unintentionally expelled prior to the onset of active labor.

The slow-release PGE2 vaginal system reduced the time from randomization to the onset of active labor and to vaginal delivery in pregnant women after PROM, without impacting the mode of delivery maternal and neonatal complications rates, or satisfaction rate compared to expectant management approach. Early induction of labor following PROM with a PGE2 vaginal system represents an effective and safe alternative to expectant labor management.

This study is registered at https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ (registration number: NCT05430711).

Premature rupture of membranes (PROM) refers to the rupture of the fetal membranes and subsequent drainage of amniotic fluid before the onset of labor. PROM affects approximately 8% of pregnancies prior to the onset of regular contractions after 37 weeks (PROM at term) and typically leads to a rapid onset of labor [1]. In the absence of induced labor spontaneous labor initiates in approximately 60% of women within 24 hours and in over 95% within 72 hours [2]. Prolonged latency between PROM and delivery increases the risk of maternal infection, particularly chorioamnionitis and postpartum endometritis. Additionally, PROM is a known risk factor for early neonatal sepsis, though studies have yet to establish consistent correlations [3].

The management of PROM has been the subject of several studies. A 2017 Cochrane meta-analysis demonstrated the benefits of early labor induction compared to expectant management following PROM. Women who underwent early induction (upon arrival at the delivery unit or within 12 hours after PROM) had a lower incidence of maternal infection and lower rates of early neonatal sepsis, without an increased risk of cesarean section or severe maternal/neonatal morbidity [4]. The included studies evaluated labor induction using oxytocin, misoprostol (prostaglandin E1, PGE1), or dinoprostone (prostaglandin E2, PGE2) in the form of vaginal tablets or gel. However, studies using PGE2 in the form of a vaginal delivery system were not included in this meta-analysis [4].

Based on these findings, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends immediate induction of labor for women with PROM upon arrival in the delivery unit, though brief expectant management is also acceptable based on patient preference [5]. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) advises offering pregnant women with PROM the option of either immediate induction or expectant management for up to 24 hours [6].

The efficacy and safety of different induction methods in PROM cases have been

examined in various studies. Most have reported no significant differences in

outcomes between misoprostol and oxytocin for induction of labor, regardless of

initial Bishop score [2, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. Studies by Liu et al. [13] and

Güngördük et al. [14] reported higher rates of vaginal

delivery in the group treated with the PGE2 vaginal delivery system, followed by

oxytocin as needed, compared to the group managed with oxytocin alone for labor

induction in women with PROM and an initial Bishop score

There is limited comparative research on early induction with a PGE2 vaginal delivery system versus expectant management. A retrospective study by Larrañaga-Azcárate et al. [16] of 744 women with PROM found a significantly lower rate of cesarean delivery in those who received immediate PGE2 vaginal delivery system induction compared to expectant management. In this study, labor was initiated with a PGE2 vaginal delivery system, removed 12 hours after PROM, followed by oxytocin infusion in both groups. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups for other outcomes.

Multiple studies support the safety and efficacy of different PROM induction methods, including PGE2 vaginal delivery systems [7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. However, research comparing expectant management (up to 24–36 hours post-PROM) to induction with a PGE2 vaginal delivery system beginning 4–12 hours post-PROM is uncommon. This prospective, randomized study aimed to assess the efficacy, safety, and maternal satisfaction associated with the use of a PGE2 vaginal delivery system compared to an expectant management approach in labor following PROM at term.

The prospective randomized study was conducted between July 2022 and March 2024 at the Clinical Department of Perinatology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Medical Center Ljubljana, Slovenia. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Commission of the Republic of Slovenia (certificate number: 0120-115/2019/13) and was registered on https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ (registration number: NCT05430711). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants voluntarily provided informed consent following a thorough explanation of the study, ensuring anonymity.

Pregnant women meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1, Ref. [17]) were eligible to participate. The assessment of criteria was determined by the attending physician (either a specialist or a resident in gynecology and obstetrics).

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | ||

| – Age |

– Bishop score |

– Active phase of labor | – Meconium stained amniotic fluid |

| – 4–12 hours from PROM | – Women with no more than two previous deliveries | – Proven colonization with GBS (unknown status is not an exclusion factor) | – Contraindication for vaginal delivery or labor induction with prostaglandins |

| – Gestation 37 0/7–42 0/7 | – Reassuring CTG trace | – Clinical suspicion of an ongoing inflammatory process | – Known IUGR (EFW |

| – Singleton pregnancy in cephalic presentation | |||

PROM, premature rupture of membranes; Bishop score [17], evaluation of the cervix according to Bishop; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; EFW, estimated fetal weight; CTG, cardiotocography; GBS, Group B Streptococcus.

Following the determination of the initial sample size, with a minimum of 35 participants per group, a total of 80 cards were prepared for randomization. Forty cards were labeled ‘Control Group’ and 40 cards ‘Intervention Group’. All cards were identical in appearance to ensure allocation concealment. The cards were thoroughly shuffled manually by a neutral third party who was not involved in participant recruitment or the conduct of the trial, ensuring unbiased randomization. Each card was then placed into a sealed, opaque envelope, taking care to make the envelopes indistinguishable from one another to prevent visual or tactile identification of the group allocation. Once sealed, the envelopes were shuffled again to eliminate any potential patterns and stored securely until use.

On the day of the trial, participants diagnosed with PROM in the outpatient setting were admitted. Randomization occurred 4–12 hours after PROM. Eligible participants were asked to select a sealed envelope at random and were subsequently assigned to one of the two groups based on the allocation indicated on the card inside. Both the attending physicians and participants remained unaware of the group assignment until after informed consent was provided. Due to the nature of the intervention, this study was designed as an open-label randomized controlled trial without blinding.

(1) Intervention Group—Induction with Propess®: In

this group Propess® (PGE2) 10 mg vaginal delivery system (Ferring

GmbH, Kiel, Germany) was inserted into the posterior vaginal fornix. Fetal status

was monitored by cardiotocography (CTG) every 8 hours, with vaginal examinations

performed only in the presence of contractions or significant changes in maternal

or fetal condition. If the vaginal delivery system failed to initiate labor 24

hours after its insertion, a vaginal examination was performed and labor was

further managed in the delivery unit with an oxytocin infusion if contractions

did not occur spontaneously. In cases of uterine contractions or signs of

maternal or fetal deterioration, the PGE2 system was removed, and the patient was

transferred to the delivery unit. If the PGE2 vaginal system was inadvertently

removed, a vaginal examination was performed; patients with a Bishop score of

(2) Control Group—Expectant Management: Participants in this group were monitored similarly to those in the induction group. When advanced cervical changes, contractions, or signs of maternal or fetal deterioration were observed, the patients were transferred to the delivery unit. A vaginal examination was performed 24 hours after randomization, followed by transfer to the delivery unit for labor induction or augmentation with oxytocin as required. Antibiotic therapy was administered upon admission under the same conditions as in the induction group.

The vaginal delivery system used in the study, Propess® vaginal delivery system contained 10 mg of dinoprostone, releasing PGE2 at 0.3 mg/hour over 24 hours. This slow, sustained release aimed to simulate spontaneous labor with a similar adverse effect profile to other PGE2 forms. The system allowed for easy removal in cases of uterine hyperstimulation, with expected effect cessation within 15 minutes.

After admission to the delivery unit, participants in both groups received standard labor management per established clinical guidelines. Labor was induced or augmented with oxytocin as needed. For those who received the PGE2 system, oxytocin administration could begin as early as 30 minutes following the removal of the PGE2 system. Postpartum management was identical for both groups, adhering to established protocols. Participants with PROM to delivery intervals exceeding 12 hours received standard antibiotic prophylaxis: first-generation cephalosporin (cefazolin 2 g (Krka d.d., Novo Mesto, Slovenia) intravenously upon labor ward admission, followed by two additional doses of 1 g intravenously every 8 hours) or, in cases of penicillin allergy, clindamycin (Lek d.d., Ljubljana, Slovenia) 900 mg intravenously upon admission, with two subsequent doses of 900 mg intravenously every 8 hours. Additional evaluations and treatments were conducted according to the clinical status of the mother and newborn. Before discharge, participants completed a questionnaire assessing satisfaction and their experience with antenatal care.

Data were collected for both groups on maternal clinical and obstetric characteristics, time intervals, neonatal outcomes, and maternal satisfaction (outlined in Table 2).

| Primary outcome measure | |

| Time from randomization to delivery | |

| Secondary outcome measure | |

| Time from randomization to vaginal delivery (without the need for operative interventions such as forceps, vacuum extraction, or cesarean section) | Time from PROM to delivery |

| Cesarean delivery rate | Instrumental delivery rate |

| Use of oxytocin | Use of antibiotics (use of antibiotics during labor and the postpartum period) |

| Hyperstimulation with non-reassuring fetal heart rate tracing (defined as an exaggerated uterine response consisting of uterine hypertonus, a single uterine contraction lasting 2 or more minutes or uterine tachysystole with a least 12 contractions in 20 minutes, with a simultaneous non-reassuring fetal heart rate tracing as defined by the 2015 FIGO classification of intrapartum cardiotocography) | Rate of chorioamnionitis (defined as a fever of 38.0 °C or more plus 1 or more of the following: baseline fetal heart rate |

| Rate of endometritis (postpartum patient with at least two of the following signs or symptoms: fever |

Fever of unknown origin (defined as a fever of 38.0 °C or more) |

| Rate of early neonatal sepsis (infants with early neonatal sepsis, a diagnosis based on a positive blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or urine microbiological culture in the first 72 hours after birth) | Apgar Scores (infants with a 5-minute Apgar Scores of less than 7) |

| Arterial umbilical cord blood pH | Neonatal intensive care unit admission |

| Maternal length of hospitalization (total length of hospitalization of women in days) | Maternal satisfaction with prenatal care provided before labor |

PROM, premature rupture of membranes; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

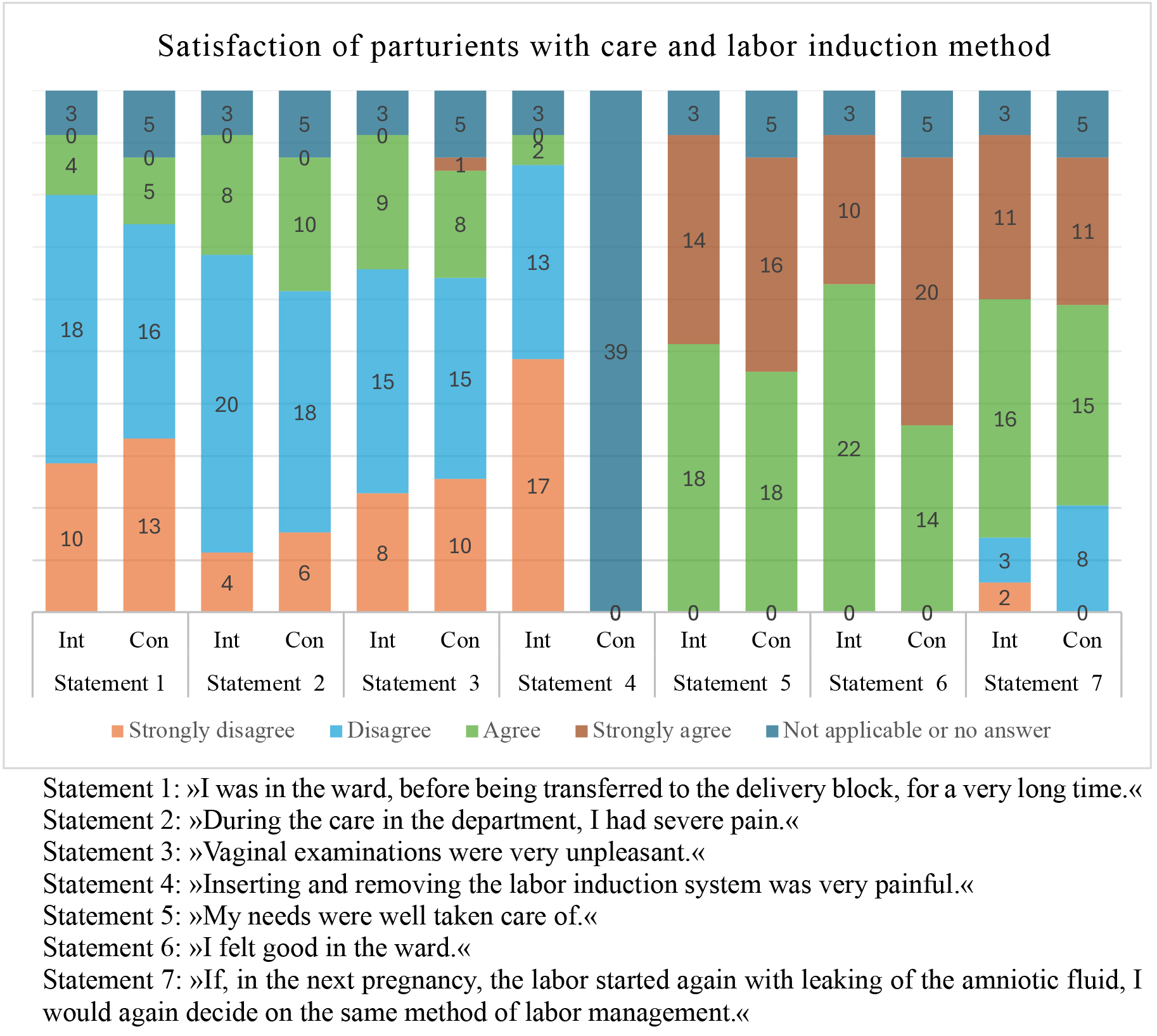

Maternal satisfaction with antenatal care and the method of labor induction was assessed through a post-delivery evaluation questionnaire through a 4-point Likert scale (1: strongly disagree; 2: disagree; 3: agree; 4: strongly agree). The statements evaluated were as follows:

– I was in the ward, before being transferred to the delivery block, for a very long time.

– During the care in the department, I had severe pain.

– Vaginal examinations were very unpleasant.

– Inserting and removing the labor induction system was very painful.

– My needs were well taken care of.

– I felt good in the ward.

– If, in the next pregnancy, the labor started again with leaking of the amniotic fluid, I would again decide on the same method of labor management.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software (version 21.0; SPSS Inc.,

Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were generated by calculating means and

standard deviations. Comparative analysis of categorical variables was performed

using the

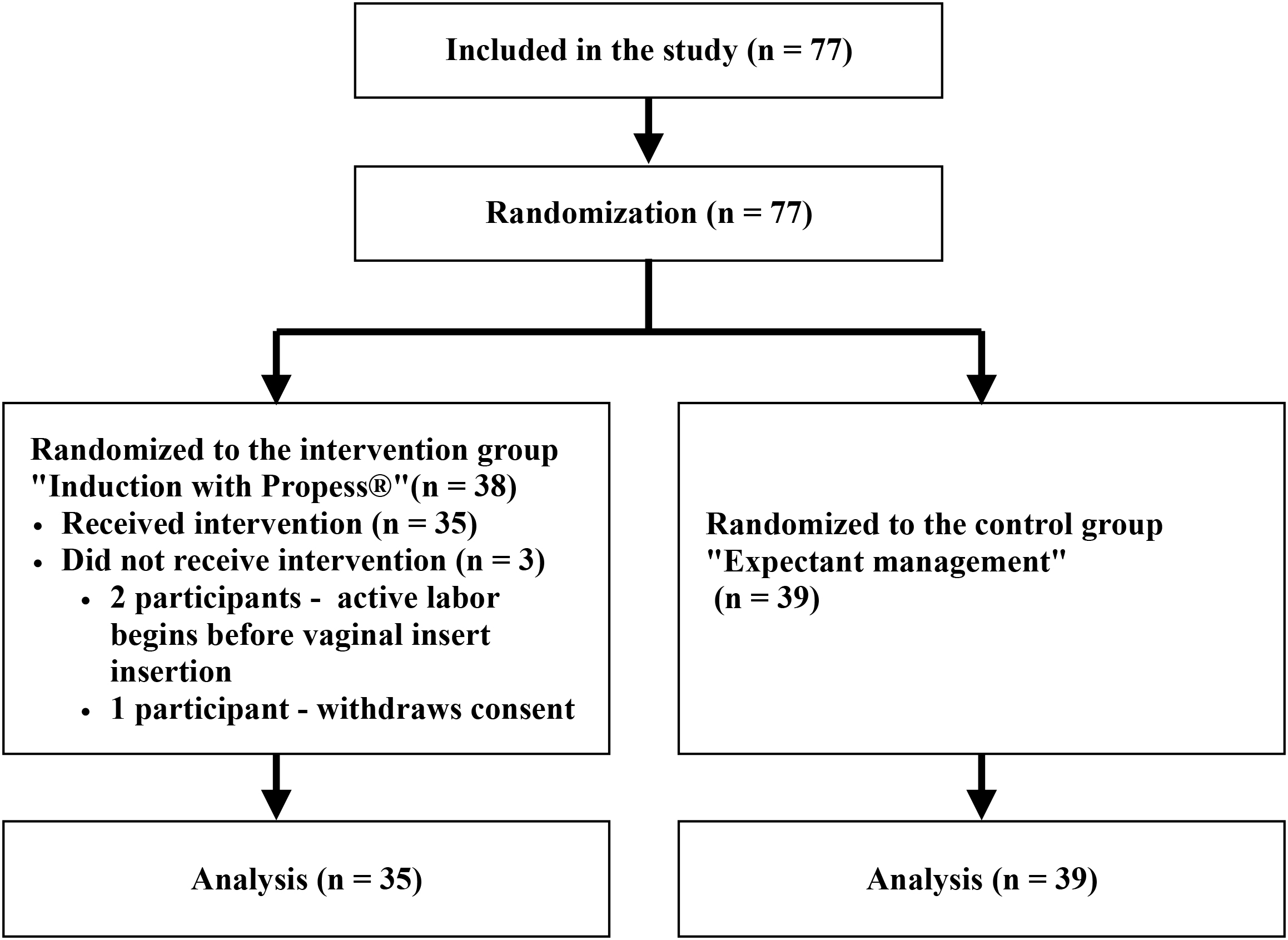

Seventy-four patients who met the inclusion criteria were included, with 35 participants assigned to the intervention group and 39 to the control group. Fig. 1 illustrates the patient enrollment process and subsequent data acquisition.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Research flow chart.

Demographic data for both groups are presented in Table 3. Except for the status of maternal colonization with Group B Streptococcus (GBS), no statistically significant differences were observed between the demographic characteristics of the 2 groups. The Bishop score was calculated at the time of randomization.

| Intervention group (n = 35) | Control group (n = 39) | p-value | t/χ2 | ||

| Age (years) (mean, SD) | 30.1 (5.3) | 30.3 (4.9) | 0.872 | t = 0.162 | |

| Body weight at conception (kg) (mean, SD) | 66.2 (15.1) | 65.6 (11.8) | 0.852 | t = 0.188 | |

| Body mass index at conception (kg/m2) (mean, SD) | 23.7 (4.9) | 23.6 (4.1) | 0.934 | t = 0.083 | |

| Number of previous births | |||||

| 0 | 30 (85.7%) | 33 (84.6%) | 0.878 | χ2 = 0.261 | |

| 1 | 4 (11.4%) | 4 (10.3%) | |||

| 2 | 1 (2.9%) | 2 (5.1%) | |||

| Pre-existing medical conditions | |||||

| Yes | 4 (11.4%) | 7 (17.9%) | 0.438 | χ2 = 0.620 | |

| Pregnancy-associated medical conditions | |||||

| Yes | 11 (31.4%) | 19 (48.7%) | 0.134 | χ2 = 2.290 | |

| Status of maternal colonization with GBS | |||||

| Unknown | 15 (42.9%) | 8 (20.5%) | 0.039 | χ2 = 4.300 | |

| Week of gestation at inclusion | |||||

| 37 | 7 (20.0%) | 9 (23.1%) | 0.559 | χ2 = 2.990 | |

| 38 | 5 (14.3%) | 7 (17.9%) | |||

| 39 | 9 (25.7%) | 12 (30.8%) | |||

| 40 | 13 (37.1%) | 8 (20.5%) | |||

| 41 | 1 (2.9%) | 3 (7.7%) | |||

| Gestational age at inclusion (weeks) (mean, SD) | 38.9 (1.2) | 38.7 (1.3) | 0.561 | t = 0.584 | |

| Bishop score at randomization | |||||

| 20 (57.1%) | 16 (41.0%) | 0.166 | χ2 = 1.920 | ||

| 4–6 | 15 (42.9%) | 23 (59.0%) | |||

| Bishop score at randomization (mean, SD) | 3.03 (1.3) | 3.49 (1.1) | 0.103 | t = 1.650 | |

Annotation: Pre-existing medical conditions—patients with a known medical

conditions (e.g, chronic lung disease, chronic hypertension, antiphospholipid

syndrome) or those with a history of major surgery; pregnancy-associated

conditions—patients with gestational diabetes, history of bleeding during

pregnancy, hepatopathy, thrombocytopenia, or other significant

pregnancy-associated conditions. GBS, Group B Streptococcus. Values in bold

indicate statistical significance (p

The data in Table 4 illustrate the indications for transferring participants to the delivery unit, stratified by group and Bishop score at randomization. A significantly higher proportion of participants in the intervention group (77%) entered active labor and were subsequently transferred to the delivery unit compared to the control group (54%) (p = 0.036).

| Indication for transfer to the delivery unit | Onset of active labor | Transferred for labor induction | Vaginal system unintentionally removed | Excessive uterine activity or meconium stained liquor | p-value (all indications)* | p-value (onset of active labor)** |

| All groups (n = 74) | 48 (65%) | 21 (28%) | 4 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 0.003; χ2 = 13.62 | 0.036; χ2 = 4.393 |

| Intervention group (all Bishop scores) (n = 35) | 27 (77%) | 4 (11%) | 4 (11%) | 0 | ||

| Control group (all Bishop scores) (n = 39) | 21 (54%) | 17 (44%) | / | 1 (3%) | ||

| Comparison of subgroups according to Bishop score at randomization | ||||||

| Intervention group (Bishop score 1–3) (n = 20) | 13 (65%) | 4 (20%) | 3 (15%) | 0 | 0.040† | 0.313 |

| Control group (Bishop score 1–3) (n = 16) | 7 (44%) | 9 (56%) | / | 0 | ||

| Intervention group (Bishop score 4–6) (n = 15) | 14 (93%) | 0 | 1 (7%) | 0 | 0.015† | 0.056 |

| Control group (Bishop score 4–6) (n = 23) | 14 (61%) | 8 (35%) | / | 1 (4%) | ||

Annotation: Transferred for labor induction—Parturient

transferred for augmentation or induction of labor with oxytocin as

*p-value for all indications for transfer to delivery unit;

**p-value for indication onset of active labor;

†p-values in subgroup comparisons are based on

Fisher’s exact test due to small sample sizes and expected cell counts

Table 5 provides data on labor progression from PROM to delivery and maternal and neonatal outcomes for both groups. Statistically significant differences were observed in the time from randomization to spontaneous vaginal delivery (p = 0.029), while other variables, including overall time from randomization to delivery, time from PROM to delivery, need for oxytocin, and mode of delivery, showed no significant differences between the groups.

| Intervention group (n = 35) | Control group (n = 39) | p-value | t/χ2/U | ||

| Labor induction and delivery timing | |||||

| Time from randomization to delivery (hours) – all deliveries (mean, SD) | 16.43 (7.47) | 19.85 (8.23) | 0.067 | t = 1.860 | |

| Time from randomization to delivery (hours) – spontaneous vaginal deliveries (mean, SD) | 15.41 (6.77) | 19.71 (8.48) | 0.029 | t = 2.230 | |

| Time from PROM to delivery (hours) (mean, SD) | 25.37 (8.58) | 26.26 (8.05) | 0.650 | t = 0.457 | |

| Need for oxytocin during labor and dosage | |||||

| Need for oxytocin during labor | 23 (65.7%) | 33 (84.6%) | 0.060 | χ2 = 3.580 | |

| Amount of oxytocin used (IE) (p25; p50; p75) | 0; 0.5; 2.7 | 0.5; 1.5; 4.0 | 0.064 | U = 512 | |

| Mode of delivery | |||||

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 32 (91%) | 31 (79%) | 0.343 | χ2 = 2.139 | |

| Operative vaginal delivery | 1 (3%) | 2 (5%) | |||

| Cesarean section | 2 (6%) | 6 (15%) | |||

| Labor and postpartum complications | |||||

| Hyperstimulation | 0 | 0 | / | / | |

| Endometritis | 0 | 0 | / | / | |

| Chorioamnionitis | 1 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | / | / | |

| Fever of unknown origin | 1 (2.6%) | 1 (2.6%) | / | / | |

| Neonatal outcomes | |||||

| Apgar Scores |

35 (100%) | 38 (97.4%) | 1.000* | / | |

| Arterial umbilical cord blood pH | 7.23 |

7.23 |

0.903 | t = 0.122 | |

| Neonates admitted to NICU | 2 (5.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | / | / | |

| Evidence of early neonatal sepsis | 0 | 0 | / | / | |

| Hospitalization duration | |||||

| Mean duration (days, SD) | 4.28 |

4.25 |

0.945 | t = 0.700 | |

Annotation: pH measurements in the arterial umbilical cord were unavailable for

three participants due to the inability to collect samples after birth.

Consequently, the analysis included 34 participants in the intervention group and

37 in the control group. *Fisher’s Exact Test (2-sided) used due to small

expected frequencies. NICU, neonatal intensive care unit. Values in bold

indicate statistical significance (p

Three patients required operative vaginal delivery, all due to obstructed labor. In the intervention group, 2 cesarean sections were performed, both among participants with an initial Bishop score of 1–3 and both due to cephalopelvic disproportion. In the control group, 6 cesarean sections were performed: 5 among participants with an initial Bishop score of 4–6 and 1 with a score of 1–3. Indications for cesarean included 3 cases due to cephalopelvic disproportion, 2 cases of failed induction, and 1 case of a pathological CTG record where chorioamnionitis was suspected.

As shown in Table 5, no differences were observed between the groups in terms of postpartum complications and neonatal outcomes. Two neonates required admission to the neonatal intensive care unit; however, neither exhibited signs of early neonatal sepsis. Additionally, the total duration of hospitalization did not differ significantly between the groups.

In a significant proportion of participants (37%) in the intervention group, the vaginal PGE2 delivery system was unintentionally removed from the vagina prior to the onset of active labor. On average, participants in the intervention group had the PGE2 vaginal delivery system inserted for 8.66 hours. The time from randomization to admission to the delivery unit was significantly shorter in the intervention group (10.14 hours) compared to the control group (12.74 hours) (p = 0.043) (Table 6).

| Dinoprostone vaginal delivery system accidentally removed (n = 35) | Time from insertion to removal of the vaginal delivery system (hours, mean, SD) (n = 35) | Intervention group—time from randomization to active labor (hours, mean, SD) (n = 35) | Control group—time from randomization to active labor (hours, mean, SD) (n = 39) |

| Yes: 13 (37%) | 8.66 (5.24) | 10.14 (5.15) | 12.74 (6.71) |

Annotation: Time from randomization to active labor demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in the intervention group compared to the control group (p = 0.043).

Questionnaires assessing satisfaction and experiences with antenatal care were unavailable for 8 parturients. Analysis of satisfaction data from 66 parturients (32 from the intervention group and 34 from the control group) revealed no statistically significant differences between the groups, except for the response to statement 6: “I felt good in the ward”. A significantly higher proportion of parturients in the control group strongly agreed with this statement (p = 0.047). Satisfaction levels of mothers in labor are depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Parturient women’s satisfaction with care and choice of labor induction method. Statement 4 was not applicable to participants in the control group, as they did not undergo labor induction via a vaginal delivery system. Int, intervention group; Con, control group.

Using a prospective randomized controlled trial, we evaluated the effectiveness, safety, and satisfaction of parturients with two different management strategies for labor after PROM at or beyond 37 weeks of gestation. Specifically, we compared expectant management (up to 24–36 hours after PROM, followed by labor induction with oxytocin) with early induction of labor using a vaginal delivery system with PGE2 (Propess®) 4–12 hours after PROM. According to our study, early induction of labor with a PGE2 vaginal delivery system compared to expectant management from PROM at term yields similar outcomes in terms of cesarean delivery rates and maternal and neonatal complications. However, active management was more effective in initiating active labor and shortened the time to spontaneous vaginal delivery compared to expectant management. This reduction in time may highlight the benefits of active management from PROM at term.

Previous studies [12, 13, 14, 15, 16] have demonstrated the efficacy of using a vaginal delivery system with PGE2 in the management of labor after PROM, but there have been few studies directly comparing this method with expectant management. Our study showed a statistically significant difference in the onset of labor between the 2 approaches. In the group that received the vaginal delivery system with PGE2 (intervention group), 77% of participants experienced the onset of active labor within 24–36 hours after PROM, compared to only 54% in the control group. Other studies [13, 18] have demonstrated that the use of PGE2 can reduce the need for oxytocin induction, a trend also observed in our study. Specifically, 56% of pregnant women in the control group with a Bishop score of 1–3 required oxytocin induction, compared to only 20% in the intervention group. Additionally, in the subgroup with a Bishop score of 4–6, oxytocin induction was required in 35% of the control group, whereas no participants in the intervention group required this intervention. Although these findings were not statistically significant, they align with results from prior research [13, 18], supporting the potential benefit of PGE2 in reducing the need for oxytocin induction. This observation is also consistent with a study comparing expectant management and labor induction using oral misoprostol [19], which similarly reported that active management significantly shortened the latency period.

We did not find any statistically significant differences in the mode of delivery between the groups, although there was a trend towards higher frequency of cesarean section in the control group. Fifteen percent of women in the control group had emergency cesarean sections, compared to only 6% in the intervention group. These findings are consistent with those reported in previous studies [12, 13, 15]. A study by Yuan et al. [20] found that induction of labor using vaginal dinoprostone within 6 hours after PROM for singleton pregnancies with an unfavorable cervix was significantly associated with a lower rate of cesarean sections compared to induction of labor within 6–24 hours after PROM. This suggests that administering vaginal dinoprostone even earlier than within the 4–12 hours window as used in our study may be beneficial.

Our findings, indicating a low incidence of fetal compromise during labor, align with the study by the Fetal Medicine Foundation group [21], which evaluated various indications for induction and observed that cases of PROM carry a comparatively lower risk of fetal compromise than conditions such as intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) or postterm pregnancy. In our study, the only cesarean section performed due to a pathological CTG record occurred in the control group. This case was further marked by neonatal compromise, as evidenced by an Apgar Scores below 7 at 5 minutes. The low incidence of fetal compromise observed in our study can be explained by the strict exclusion criteria for randomization. These criteria specifically excluded cases with known IUGR, defined as an estimated fetal weight below the 3rd centile, the presence of meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and non-reassuring CTG findings. This strategic approach likely minimized the risk of fetal distress during the study.

There were no significant differences between the research groups in the incidence of perinatal or postnatal complications for either the mother or the newborn. All neonates transferred to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit did so due to a suspected inflammatory event; however, none showed evidence of early neonatal sepsis. Our findings align with previous meta-analyses that highlight the benefits of early induction of labor after PROM [3].

In our study, the vaginal PGE2 delivery system was unintentionally removed in 37% of participants in the intervention group. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies on the use of vaginal delivery systems after PROM have reported the incidence of vaginal system dislodging [15, 20]. This removal proved to be one of the main challenges when using PGE2 for labor induction after PROM, as it reduced the effective period of the active ingredient’s action. On average, the vaginal delivery systems were in place for 8.66 hours, despite the fact that the device is designed to release the active ingredient over 24 hours. While the frequency of failure of the vaginal delivery system has not yet been fully quantified, this issue has a significant impact on treatment costs, the number of vaginal examinations required, and the need for additional interventions. Therefore, it may be advisable to consider alternative forms of prostaglandin administration after PROM.

One of the strengths of our study is the inclusion of satisfaction rates from participating women. The research revealed that women were equally satisfied with both methods of managing the period between PROM and the onset of active labor, with similar responses regarding the length of hospitalization and pain in both groups. Vaginal examinations were equally unpleasant for women in both groups, and the insertion of the vaginal delivery system with PGE2 did not cause significant pain for the majority of participants. All women felt their needs were well addressed and reported feeling good with their care prior to active labor. The only notable difference was in the responses to statement 6: “I felt good in the ward”, where significantly more women in the control group expressed the highest level of agreement. This may be due to a longer period before the onset of painful contractions or a sense of greater control over labor, as it proceeded without additional interventions like induction [22]. Since responses to statement 7: “If labor started again with leaking amniotic fluid in my next pregnancy, I would choose the same method of labor management”, were equally distributed between the 2 groups, we can conclude that parturients were satisfied with both methods of labor management.

A key strength of our study is its prospective design, along with the comparable characteristics observed in both groups. The only statistically significant difference was in the proportion of women with unknown GBS colonization status between the intervention (43%) and control groups (21%), which is likely due to chance, but could potentially compromise the validity of the maternal and neonatal outcome analyses. With the introduction of free universal GBS screening in Slovenia, starting in April 2023, we anticipate an increase in the detection of women with positive vaginal and rectal swabs for GBS. Given the risk of vertical transmission of GBS and the associated increased risk of early invasive neonatal infection, these women require specialized management, which includes perinatal antibiotic prophylaxis and a reduced time between PROM and delivery [23]. Our study’s findings could be especially valuable for pregnant women with a positive GBS screening, as we demonstrated that the use of a vaginal system with PGE2 after PROM is effective in shortening the time to active labor, without compromising the safety or satisfaction of women in labor.

The limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size. While no significant complications were observed in either group, the limited sample size may have hindered the detection of rare adverse events. Furthermore, the relatively small sample size likely prevented us from identifying significant differences in some of the measured outcomes. We conducted a post-hoc power analysis to assess the adequacy of our sample size. For a statistical power of 80%, a total of 72 participants per group would have been required to detect a statistically significant difference in our primary outcome—the time interval from randomization to delivery. When defining the group size prior to the study, we anticipated greater differences in the time interval from randomization to delivery between the intervention and control groups. Consequently, the initial sample size was too small to reach statistically significant differences. An additional study with a larger sample size could provide more robust results.

Another limitation is that the study was conducted at a single institution, which limits the external validity of the results and affects the ability to generalize the findings. However, the relevance of our findings could extend to other major obstetric centers, particularly given our role as Slovenia’s largest tertiary medical facility, responsible for managing about one-third of the nation’s births and a wide range of pregnancy referrals.

Despite the limitations of our study, such as the small sample size and its single-center design, the results indicate that the vaginal PGE2 delivery system is a safe and effective alternative to expectant management, leading to a shorter time from application to onset of active labor when compared to the traditional approach. Women at term with PROM should be informed that induction of labor is a viable option if they prefer this approach.

The vaginal system utilizing PGE2 shortens the time to onset of active labor in pregnant women after PROM. Within 24 hours, spontaneous labor occurred in 54% of expectantly managed women, compared to 77% in those who received the vaginal PGE2 system. Unfortunately, 37% of vaginal delivery systems were inadvertently removed, which undermines the duration of its action. PGE2 vaginal system was both effective and safe, as it did not lead to higher maternal or neonatal morbidity, with no significant difference in maternal satisfaction compared to expectant management.

The authors serve as custodians of the anonymized data, which may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conceptualization: BP, PP; methodology BP, PP; data curation: BP, PP; statistical analysis: BP; writing—original draft preparation: BP, writing, review and editing: BP, PP; supervision: PP. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Commission of the Republic of Slovenia (Ethic Approval Number: 0120-115/2019/13), and all of the participants provided signed informed consent.

We sincerely thank the physicians, midwives, and all other healthcare workers who contributed to this study and the Clinical Department of Perinatology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Medical Center Ljubljana, Slovenia, for their collaboration and support.

This work was supported by the Department of Perinatology, Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology, research grant for tertiary projects (grant number: TP 20240106), University Medical Centre, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT-3.5 and Microsoft Copilot to check spelling and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the final publication.

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.