- Academic Editor

Balloon tamponade is an effective intervention for managing postpartum hemorrhage, particularly in resource-limited settings. However, cervical relaxation during balloon insertion may cause balloon slippage, resulting in placement failure. This complication is associated with increased blood loss, a higher risk of hysterectomy, and unnecessary use of resources.

We conducted a retrospective analysis of 10 patients who underwent modified cervical cerclage balloon fixation combined with cervical clamping for postpartum hemorrhage complicated by balloon slippage. These patients were treated between January 1, 2021, and January 1, 2024, at two hospitals in Cheng Du and Xizang, China. The primary outcome was successful hemostasis following intervention. Secondary outcomes included perioperative blood loss and drainage volume. Data analysis was performed using descriptive statistics and the Shapiro-Wilk test.

The modified method was applied in 10 patients. Hemostasis was successfully achieved in 9 of 10 cases (90%). In 1 patient, additional uterine artery embolization was required due to an arteriovenous fistula.

Modified cervical cerclage balloon fixation combined with cervical clamping is an effective and low-cost approach for preventing balloon slippage in appropriate clinical settings.

Postpartum hemorrhage remains the leading cause of maternal deaths and complications globally [1, 2]. Despite strong recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO) for its prevention and management, postpartum hemorrhage continues to account for approximately 27% of maternal deaths worldwide [3]. A systematic review by Yunas et al. [4] identified the five most frequently reported causes of postpartum hemorrhage: uterine atony, genital tract trauma, retained placenta, placenta accreta spectrum, and coagulopathy. Uterine balloon tamponade is a recommended treatment for postpartum hemorrhage, followed by surgical intervention and blood transfusion when standard first-line treatments fail [3]. Although high-quality randomized trials remain limited, particularly in low-resource settings, previous systematic reviews have reported high success rates in treating severe postpartum hemorrhage using uterine balloon tamponade [5, 6]. As no single treatment fits all cases of postpartum hemorrhage, strengthening first-line treatment programs and improving adjunctive measures remains essential.

In resource-limited areas, balloon tamponade may be particularly valuable. However, balloon spillage due to cervical relaxation during application is a common application, potentially leading to placement failure. This is of particular concern in settings with limited resources, as it can increase the risk of hysterectomy, exacerbate blood loss, and waste critical medical supplies. To address this problem, we propose a method using modified cervical cerclage balloon fixation combined with cervical clamping, based on our case reports, to effectively manage postoperative hemorrhage in appropriate clinical scenarios. Herein, we detail the modified surgical procedure.

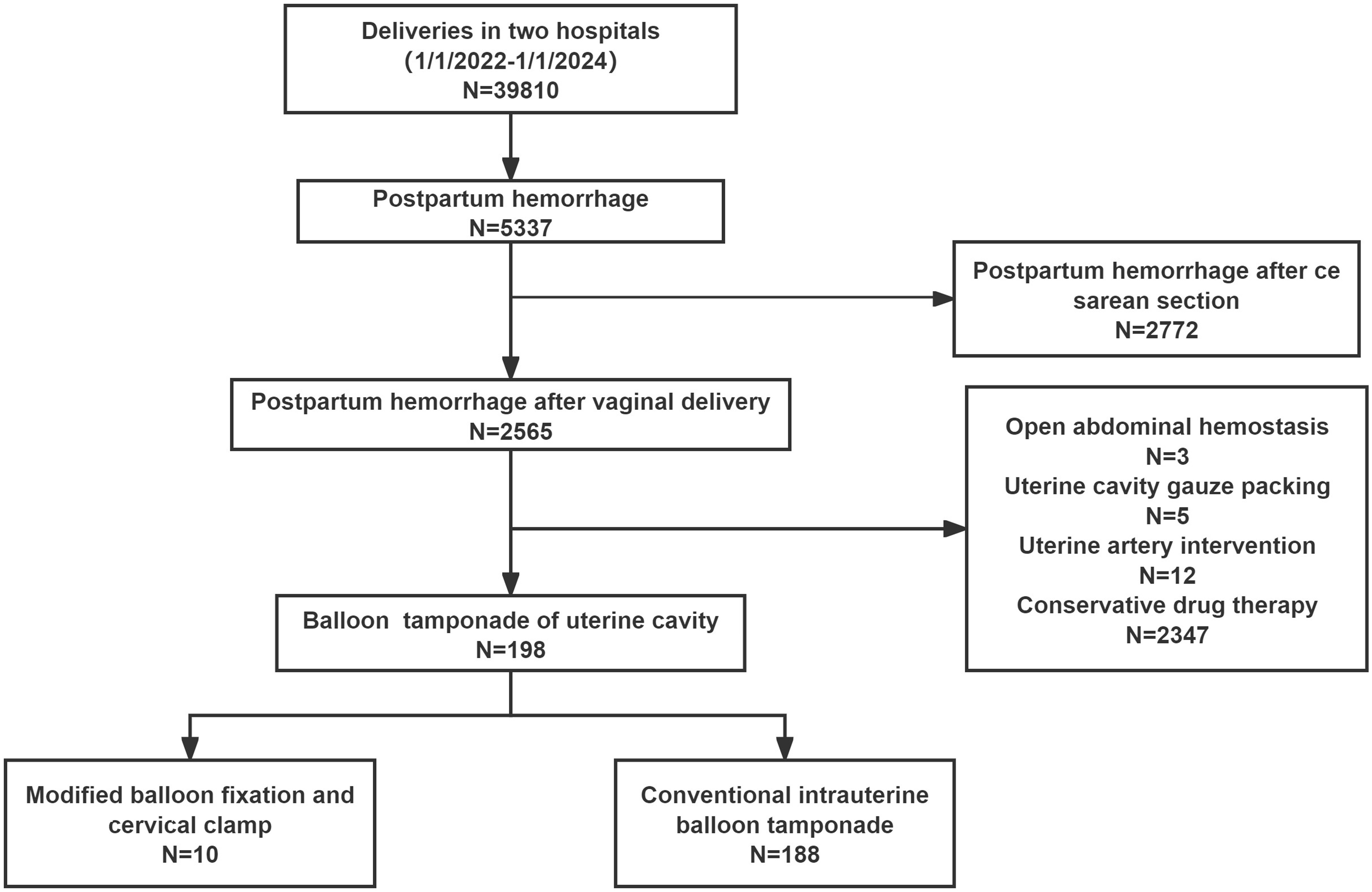

This study involved a retrospective analysis of 10 patients who required

uterine balloon tamponade for postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal delivery,

treated between January 1, 2021, and January 1, 2024, at West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, and Women and Children’s Hospital of Xizang Autonomous Region in Chengdu

and Xizang, China (Fig. 1). Inclusion criteria included patients with postpartum

hemorrhage and a fully dilated cervix requiring balloon tamponade (

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of the patients included. N, number of samples.

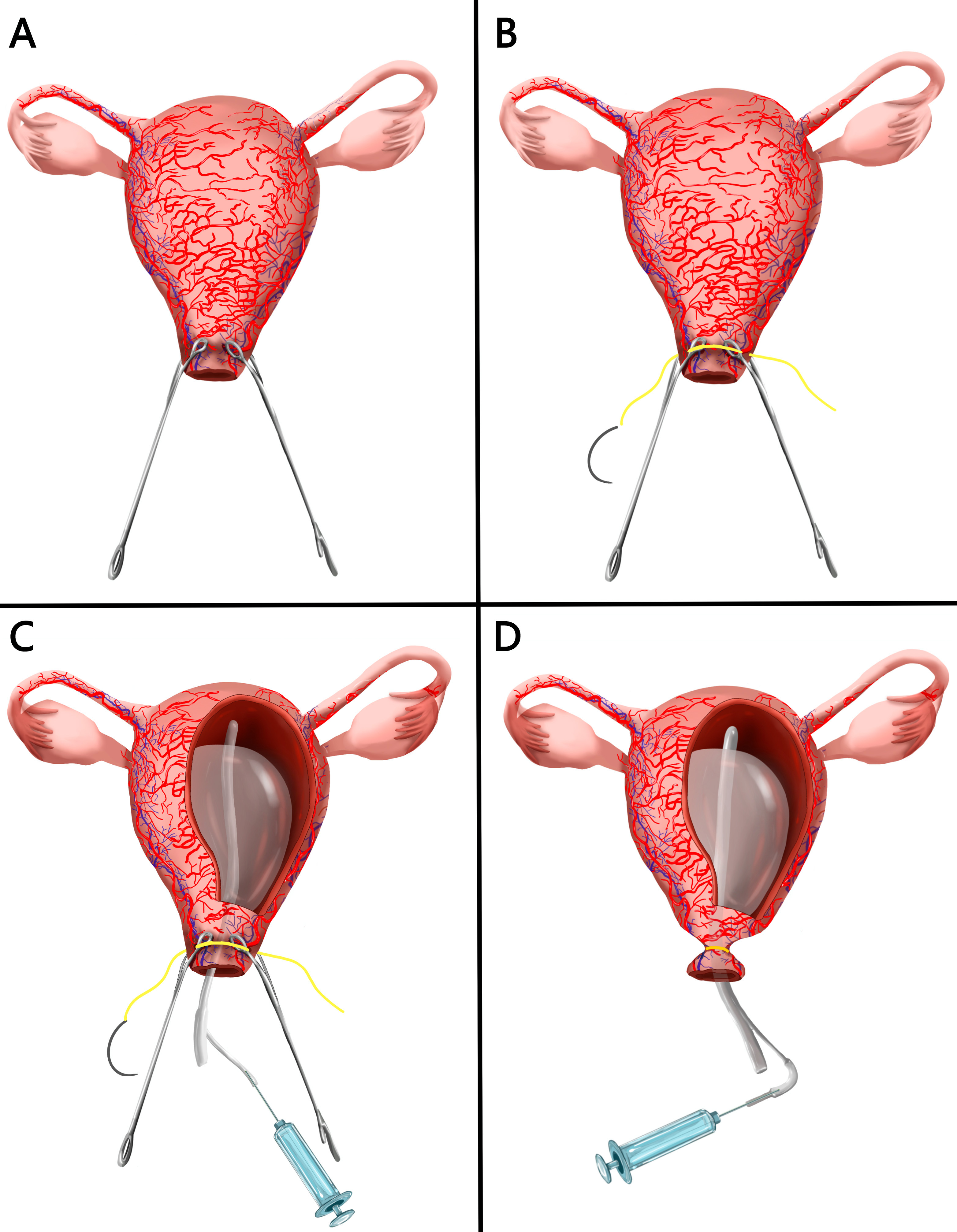

Cervical forceps were used to clamp the descending branches of the uterine artery before performing cervical cerclage to reduce bleeding. The Bakri balloon was then rapidly secured using a modified cervical cerclage. The procedural steps are described below (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The procedural steps. (A) Two oval forceps are then used to clamp the left and right sides of the cervix at the three and nine o’clock positions. (B) Quickly performed the modified cervical cerclage. (C) Balloon placement. (D) The suture is securely tied behind the cervix to help balloon fixation.

A vaginal retractor was used to expose the cervix after delivery. Two oval forceps were applied to the left and right sides of the cervix at the 3 and 9 o’clock positions (Fig. 2A), at a depth of 0.5 cm below the bladder reflex. These forceps clamped the descending branches of both uterine arteries, necessitating caution to avoid damaging the bladder or rectum. This technique helped achieve temporary hemostasis.

We placed 1-0 absorbable sutures adjacent to the oval forceps, taking care to avoid blood vessels. At each location, two stitches were placed: one inserted at the 4 o’clock position and exiting at 2 o’clock position, avoiding the 3 o’clock vascular area on the cervical side; the other inserted at the 10 o’clock position and exiting at the 8 o’clock, avoiding the 9 o’clock area on the cervical side. The suture lines are marked in yellow to represent the exit and entrance points of the needle (Fig. 2B). The modified cerclage technique is faster and simpler than conventional cervical cerclage, requiring only sutures at 3 and 9 o’clock positions, avoiding those at 12 and 6 o’clock or up to the internal cervical os. This allows rapid completion without delaying balloon placement.

The balloon was placed carefully into the uterine cavity and advanced to the fundus. Normal saline was infused into the balloon until adequate compression was achieved and visible bleeding ceased (Fig. 2C). Balloon placement was guided by ultrasonography, which was also used to confirm proper balloon positioning, assess intrauterine bleeding, and detect large blood clots.

The sutures were securely tied behind the cervix at the posterior fornix of the vagina. Oval forceps were gently released to tighten the knot, narrowing the cervical opening and effectively preventing balloon displacement (Fig. 2D). The Bakri balloon’s drainage channel was connected to continuous suction to monitor for residual bleeding in the uterine cavity.

Balloon removal followed standard uterine tamponade protocols, typically between 8 and 12 h, based on ongoing bleeding and drainage volume, not exceeding 24 h. First-generation cephalosporins were administered for 24 h as prophylaxis for infection. All medications, including oxytocin and tranexamic acid, were administered according to standard postpartum hemorrhage guidelines, with no deviations due to surgical procedure. Cerclage sutures were removed simultaneously with balloon deflation.

Patient baseline characteristics included age, body mass index (BMI), gestational age, parity, gravidity, and maternal complications during pregnancy and delivery. Perioperative data included blood loss prior to balloon placement, postoperative bleeding, drainage volume, use of modified method, combination with other methods, and outcomes.

The primary objective of this study was to determine the success rate of the modified technique, defined by prevention of balloon slippage and effective hemorrhage control. Secondary objectives included perioperative outcomes associated with the application of the modified technique. All patients underwent six-week postpartum cervical assessments to evaluate recovery.

Normality was tested for all continuous variables using the Shapiro-Wilk test

due to the small sample size (n = 10). Variables with a normal distribution are

expressed as mean

This modified technique was applied in 10 patients with balloon detachment

(Table 1). The mean maternal age was 34

| Case | Age (year) | BMI (kg/m2) | Gestational week | Gravida and parity | Previous history of surgery | High risk factor | Causes of postpartum hemorrhage |

| (Mean |

(Mean | ||||||

| 1 | 34 | 26.3 | 41 | G2P1 | no | Placental adhesion, fetal macrosomia | Placental adhesion and Uterine atony |

| 2 | 30 | 28.8 | 39 + 1 | G2P1 | no | - | Uterine atony |

| 3 | 31 | 22.2 | 39 + 5 | G3P2 | cholecystectomy | Precipitate labor | Uterine atony |

| 4 | 32 | 31.2 | 37 | G2P1 | no | Scarred uterus, uterine arteriovenous fistula | Arteriovenous fistula |

| 5 | 33 | 30.5 | 26 + 1 | G1P0 | no | Placental adhesion, twin pregnancy | Placental adhesion and Uterine atony |

| 6 | 32 | 28.2 | 40 + 5 | G3P2 | no | - | Uterine atony |

| 7 | 35 | 24.2 | 39 + 4 | G3P2 | no | - | Uterine atony |

| 8 | 36 | 25.3 | 40 | G5P2 | no | - | Uterine atony |

| 9 | 35 | 25.4 | 38 + 3 | G3P2 | no | Marginal placenta previa | Marginal placenta previa |

| 10 | 42 | 25.3 | 38 | G2P1 | no | Advanced maternal age, fetal macrosomia | Uterine atony |

| 34 |

26.7 |

Gravida (G): The total number of pregnancies a woman has had, regardless of

outcome (including live births, stillbirths, miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies,

or elective terminations). Parity (P): The number of pregnancies reaching viable

gestational age (typically

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

| Case | The amount of bleeding before balloon placement (mL) | The amount of postoperative vaginal bleeding (mL) | The amount of drainage (mL) | Preoperative hemoglobin (g/L) | Postoperative hemoglobin (g/L) | Placental residue | Modified method | Combined with other method |

| (Mean |

(Median, IQR) | (Mean |

(Mean |

(Mean | ||||

| 1 | 1500 | 52 | 110 | 138 | 107 | no | yes | no |

| 2 | 1418 | 38 | 70 | 131 | 84 | no | yes | no |

| 3 | 964 | 40 | 89 | 130 | 104 | no | yes | no |

| 4 | 2008 | 400 | 55 | 115 | 58 | no | yes | Uterine artery embolization |

| 5 | 1815 | 20 | 80 | 117 | 65 | no | yes | no |

| 6 | 890 | 49 | 30 | 126 | 91 | no | yes | no |

| 7 | 900 | 30 | 50 | 128 | 98 | no | yes | no |

| 8 | 1900 | 60 | 120 | 116 | 62 | no | yes | no |

| 9 | 1280 | 40 | 80 | 92 | 62 | no | yes | no |

| 10 | 980 | 70 | 50 | 102 | 82 | no | yes | no |

| 1366 |

44.5 (38.5, 58) | 73 |

119.50 |

81.30 |

IQR, interquartile range.

Balloon slippage was successfully prevented in all 10 patients. Hemostasis was achieved in nine patients using the modified technique. In one patient, although bleeding was reduced, it remained uncontrolled and required uterine artery embolization. An arteriovenous fistula was later identified as the underlying cause of balloon compression failure during intervention.

Postpartum hemorrhage remains a significant cause of maternal morbidity and mortality [7, 8]. Intrauterine balloon tamponade has demonstrated efficacy, with reported success rates of 78.0% to 88.9% after vaginal delivery [9, 10], and a notable reduction in postpartum hysterectomy rates from 7.8 to 2.3 per 10,000 deliveries [11]. Moreover, the administration of intrauterine balloon tamponade is associated with a decreased need for invasive interventions such as vessel ligation, arterial embolization, and hysterectomy among women undergoing vaginal delivery [12].

Systematic reviews indicate an 85% success rate for balloon tamponade, with 10%–15% of failures attributable to balloon displacement [6, 13, 14]. After vaginal delivery, cervical dilation and uterine relaxation increase the likelihood of balloon expulsion, resulting in continued bleeding, contamination of equipment, and resource wastage. Existing methods for preventing balloon slippage—such as vaginal packing, abdominal wall fixation, cervical stabilization with ring forceps left in place for 12 to 24 h, suspension of the balloon using bilateral cervical sutures, or placement of a McDonald cerclage prior to balloon inflation [13].

Vaginal packing is cost-effective but can cause vaginal mucosal injury and does not effectively stabilize or reduce the cervical os, making it difficult to ensure proper balloon placement within the uterine cavity. Moreover, obstructed vaginal blood flow compromises accurate assessment of hemorrhage and increases the risk of infection. Abdominal wall fixation, although useful, is limited to cesarean deliveries [15]. Although technically simple, the ring forceps method poses a risk of ischemic complications if clamped for prolonged periods of (12–24 h) [16].

Alternative techniques include suspending the balloon with bilateral cervical sutures or performing McDonald cerclage. In contrast, our modified cerclage is faster and simpler than conventional cervical cerclages. It requires suturing only at the 3 and 9 o’clock positions, eliminating the need for sutures at the 12 and 6 o’clock positions or extension to the internal cervical os. A full encirclement of the cervix is sufficient, enabling rapid placement without delaying balloon insertion.

Before suturing, oval forceps were applied bilaterally to the cervix to reduce bleeding, stabilize cervical tissue, and prevent balloon slippage during knot-tying. Early recognition and timely management are essential in cases of postpartum hemorrhage, as delays can result in complications or death [17]. To address balloon slippage, we developed a technique combining cervical clamps and a modified cervical cerclage for rapid and effective control. Cervical forceps were used to clamp the uterine artery prior to balloon fixation to reduce ongoing bleeding [18]. Special care was taken to avoid accidental ureteral clamping during this step. In the cerclage procedure, sutures were inserted near the outer edge of the cervical clamp, intentionally avoiding the blood vessels at the 3 and 9 o’clock positions. With clear landmarks and ease of execution, the balloon could be quickly secured in place by knotting the sutures.

Our modified approach for managing balloon slipping in postpartum hemorrhage demonstrated a 90% success rate. Although Statistical comparison was not performed due to the small sample size, but the numerical trend suggests a potential advantage. The only cause of failure was attributed to an arteriovenous fistula. Nevertheless, the technique rapidly reduced bleeding and provided sufficient time for further intervention, ultimately preserving the uterus. The method is effective, easily applicable, and promptly resolves balloon tamponade-related complications.

Our findings support the effectiveness of modified cervical cerclage balloon fixation combined with cervical clamping in addressing balloon slippage during postpartum hemorrhage. However, the retrospective study design introduces potential biases, and the limited sample size restricts the generalizability of results. This preliminary report reflects a small case series of patients treated with uterine balloon tamponade for postpartum hemorrhage across two institutions. To overcome this limitation, we intend to expand our case cohort in future research and conduct a controlled comparative study. Ongoing enrolment and long-term follow-up are planned to validate these initial findings. Although no adverse events occurred in this series, it remains possible that the additional surgical procedure may lead to complications such as bleeding, laceration, or infection [13].

The adoption of modified cervical cerclage balloon fixation combined with cervical clamping effectively addresses the problem of balloon slippage during postpartum hemorrhage. This technique represents a low-cost, simple, and easily implementable intervention that has demonstrated efficacy. Its success in reducing bleeding and preserving the uterus highlights its value as a clinically relevant solution. Overall, this method offers a promising approach for the management of postpartum hemorrhage, particularly in resource-limited settings where rapid and reliable interventions are essential.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

LH and BL were responsible for the conception of the study and manuscript drafting. LH and BL were responsible for data collection, methodology. AZ was responsible for the interpretation of data. LH and AZ contributed to the revision and final approval of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the West China Second University Hospital (approval no. 2017-033, 2022-006) and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGpt-3.5 in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.