- Academic Editor

Recently, serial ultrasound assessment of cervical length has been proposed as an alternative management of history-indicated cerclage. To investigate the efficacy of prophylactic cerclage among women who had previously experienced mid-trimester pregnancy loss by comparing the outcomes between women who chose history-indicated cerclage and those who chose serial ultrasound assessment.

We examined the medical records of women who delivered at our hospital between 2010 and 2018 and extracted cases with a history of mid-trimester pregnancy loss between 14 and 25 weeks' gestation. We compared the women with and without history-indicated cerclage. For women who choose expectant management, cervical length was assessed by transvaginal ultrasound every two weeks, and ultrasound-indicated cerclage was performed. The primary outcome was preterm birth before 28 or 34 weeks.

The study criteria were met by 63 women; among these, 28 had received history-indicated cerclage. The incidence of preterm birth at 28 and 34 weeks was similar between the two groups. However, among the 30 women who experienced painless cervical dilation at prior pregnancy loss, history-indicated cerclage showed significant low preterm birth rate compared with expectant management: 2/22 (9.1%) vs. 4/8 (50.0%) at <28 weeks (p = 0.029) and showed a lower preterm birth rate: 3/22 (13.6%) vs. 4/8 (50.0%) at <34 weeks (p = 0.06).

History-indicated cerclage can be considered in women with a history of mid-trimester pregnancy loss who experience painless cervical dilation.

A prior history of preterm birth is known to be a high-risk factor for spontaneous preterm birth [1, 2]. The mechanism for this recurrence is still not yet understood; however, cervical insufficiency is thought to be a part of the cause, especially if prior preterm delivery occurred during the second trimester. Transvaginal cervical cerclage has been indicated as a treatment option for cervical insufficiency. Currently, cerclage placement based on obstetric history at 13–14 gestational weeks is referred to as history-indicated cerclage (also known as prophylactic cerclage), as opposed to ultrasound-indicated cerclage or physical examination-indicated cerclage [3, 4, 5, 6, 7].

Although history-indicated cervical cerclage is considered for patients with cervical insufficiency, controversy remains regarding its use over serial ultrasound assessment. The widespread use of transvaginal ultrasound evaluation of cervical length has become more common to defer cerclage placement until cervical length is shortened. The question remains as to whether it is safe to undertake serial ultrasound assessment instead of history-indicated cerclage for women with a history of second trimester pregnancy loss related to painless cervical dilation. The risk of iatrogenic rupture of membranes may increase if cerclage is placed after cervical dilation [7].

In our institution, the decision of whether to perform history-indicated cerclage or serial ultrasound assessment (ultrasound-indicated cerclage if needed) is made based upon the request of the women, following Japanese guidelines [8]. The aim of this study was to compare the pregnancy outcomes between women who chose history-indicated cerclage and those who chose serial ultrasound assessment. We also assessed whether the previous mid-trimester pregnancy loss was due to a painless cervical dilation, i.e., whether or not it was truly due to cervical insufficiency.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted by collecting the medical records of women who had singleton live births at the Japanese Red Cross Aichi Medical Center Nagoya Daiichi Hospital between 2010 and 2018. This hospital is a tertiary referral center that performs approximately 1500 deliveries per year. Women who had a prior history of late miscarriage or very early preterm birth (between 14 and 25 gestational weeks) at our hospital before their current delivery were included in this study. Women who had prior mid-trimester delivery at other institutions were excluded because we could not access detailed information. We performed history-indicated cerclage according to the women’s preference after sufficient counseling. Thereafter, we compared clinical outcomes between women who chose history-indicated cerclage and those who chose expectant management. The primary outcome was defined as preterm births occurring before 28 or 34 weeks.

We focused on determining whether the preceding pregnancy history of the patients suggested “truly” suspicious cervical insufficiency or not. Thus, we divided the study subjects into two groups. Group A included women whose preceding mid-trimester delivery presented as painless cervical dilation, typically with prolapse of the membrane. The other group, Group B, consisted of cases without painless cervical dilation such as premature rupture of the membrane (PROM), sub-decidual hemorrhage, or infection. Complications associated with cervical cerclage were evaluated by cervical laceration, puerperal pyrexia, PROM, cesarean delivery due to dystocia, and estimated blood loss at delivery.

History-indicated cerclage was indicated at 13–14 gestational weeks. The women who had not history-indicated cerclage received expectant management. For those, cervical length was assessed by transvaginal ultrasound every two weeks starting at 16 weeks, and if the cervical length was shorter than 25 mm before 26 weeks, ultrasound-indicated cerclage was performed at the discretion of the physician. Taking vaginal culture and administration of antibiotics or tocolytic agents were done if necessary. Transvaginal progesterone was not used for all patients, as it was not approved by Japanese insurance.

Statistical computations were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [9]. The Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical variables of the two groups. An independent-samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was also used for continuous variables as appropriate. Statistical tests were considered significant with a p-value less than 0.05.

In the study period, a total of 63 women met the study criteria. Of these 63 women, 28 received history-indicated cerclage and 35 received expectant management. Maternal characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups except for the number of suspicious cervical insufficiency cases.

| History-indicated cerclage (N = 28) | Expectant management (N = 35) | p-value | |

| Maternal age (years) | 34.0 |

33.3 |

0.558 |

| Nulliparousa | 11 (39.3%) | 18 (51.4%) | 0.337 |

| Current smoker | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.9%) | 1.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.0 (20.0–24.3) | 20.5 (19.0–22.0) | 0.644 |

| Conization | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.580 |

| Uterine anomaly | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.444 |

| Gestational age at preceding miscarriage/PTB | 20 |

19 |

0.775 |

| Suspicions insufficiency caseb | 22 (78.6%) | 8 (22.9%) |

BMI, body mass index; PTB, preterm birth.

a Women who had never delivered after 22 weeks gestation.

b Women who had painless cervical dilation at a preceding miscarriage or PTB.

Data are presented as mean

The incidence of preterm birth was similar in both groups (Table 2). Of the women who had history-indicated cerclage, two (7.1%) delivered before 28 weeks, and one delivered at 29 weeks. Four (11.4%) of the women receiving expectant management delivered before 28 weeks. Among patients receiving expectant management, rescue cerclage was indicated due to cervical dilation at 17–23 weeks in 5/35 (14.3%) women.

| History-indicated cerclage (N = 28) | Expectant management (N = 35) | p-value | |

| PTB |

2 (7.1%) | 4 (11.4%) | 0.684 |

| PTB |

3 (10.7%) | 4 (11.4%) | 0.754 |

PTB, preterm birth.

Considering the aforementioned groups of those with cervical insufficiency or

not, all preterm births occurred in Group A, i.e., women who had painless

cervical dilation at prior pregnancy loss. No one needed rescue cerclage, and no

preterm births before 34 weeks occurred in Group B. The incidence of preterm

birth before 28 weeks in Group A was significantly lower in women who chose

history-indicated cerclage than expectant management. Preterm birth rates before

34 weeks were also lower in the history-indicated cerclage group, although not

significantly different (Table 3). Eight women who did not received

history-indued cerclage in group A were monitored every 2 weeks for cervical

length; all five patients who had a cervical length of less than 25 mm at

| History-indicated cerclage (N = 22) | Expectant management (N = 8) | p-value | |

| PTB |

2 (9.1%) | 4 (50.0%) | 0.029 |

| PTB |

3 (13.6%) | 4 (50.0%) | 0.060 |

PTB, preterm birth.

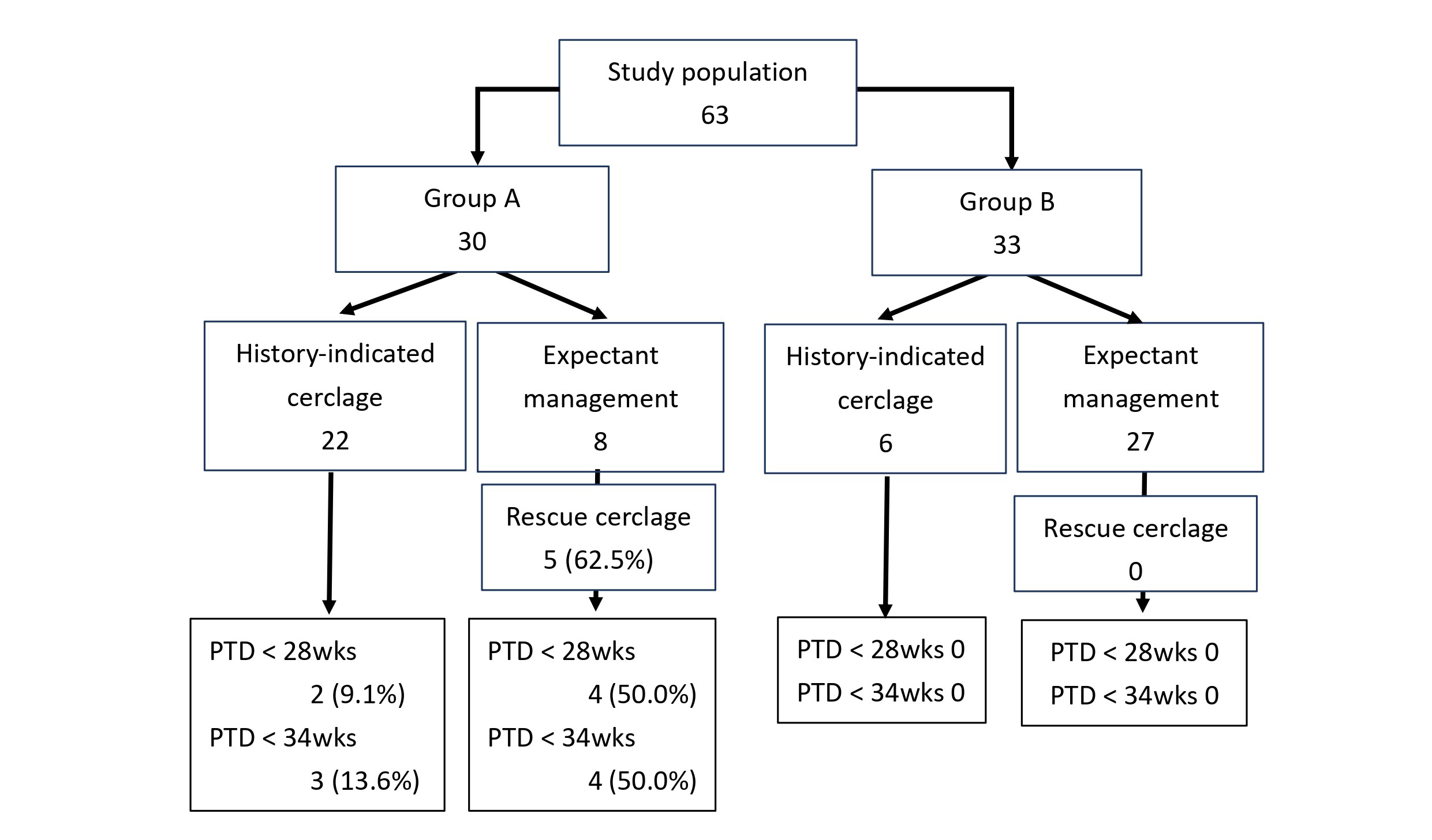

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Preterm birth rate in each management when divided into Group A (women who had painless cervical dilation at prior mid-trimester pregnancy loss) and Group B (women not in Group A; typically whose preceding mid-trimester pregnancy loss was caused by pPROM or sub-decidual hemorrhage). PTD, preterm delivery; pPROM, preterm premature rupture of the membranes.

We also collected information about obstetric complications that may be increased by cerclage. One cervical laceration and one emergent cesarean delivery due to dystocia occurred in the history-indicated cerclage group; however, there was no such case in the expectant management group. PROM occurred 6/28 (21.4%) in the history-indicated cerclage group and 5/35 (14.3%) in the expectant management group. There was no significant difference between the groups.

Our study revealed no significant differences in preterm birth rate between history-indicated cerclage and expectant management among women who had experienced mid-trimester pregnancy loss at 14–24 weeks, although history-indicated cerclage showed lower very preterm birth rates in the population who experienced mid-trimester delivery due to painless cervical dilation, typically, the membrane bridging.

A Cochrane review [10] analyzed 15 randomized controlled clinical trials. Women

considered to be at high risk of preterm birth, justifying cerclage placement,

were assigned to cerclage, alternative treatments, or no treatment. This analysis

concluded that cervical cerclage reduced the risk of preterm births, but data

were limited for all clinical groups. A recent population-based cohort study [11]

showed that history-indicated cerclage placement in women with only single

mid-trimester loss might relate to preterm delivery. In this study, 108 women

received history-indicated cerclage among 2175 patients with a singleton

pregnancy ending in birth or miscarriage from 14 to 28 weeks. Women with cerclage

were significantly more likely to deliver at

Studies [12, 13, 14, 15] have been conducted to determine whether the placement of cervical cerclage according to the shortening of the cervical length (i.e., ultrasound-indicated cerclage) is an acceptable alternative to history-indicated cerclage. The incidence of preterm delivery has been reported to be similar in history-indicated cerclage groups and ultrasound-indicated cerclage groups. These findings can be interpreted to suggest that the ultrasound-indicated protocol reduces needless intervention, although this is still unclear. In the study by Simcox et al. [12], only 19% of women randomized to the elective cerclage group underwent intervention, while 32% of women randomized to the ultrasound-indicated group received cerclage.

According to the results of this study, history-indicated cerclage may be superior to expectant management for women with a history of cervical insufficiency if their history is precisely evaluated.

This study has some limitations. First, this study was a retrospective and small-size cohort study, and the number of women who chose expectant management in group A was small. Therefore, it may be difficult to generalize the results of this study. Next, there is a selection bias in whether or not to undergo history-indicated cerclage. A randomized control study for homogenous cervical insufficiency patients is warranted, but this may be difficult because women with cervical insufficiency have a wide variety of pathology and the prevalence of each is relatively low. Lastly, intrauterine infection is also an important cause of preterm birth. Although we had confirmed placental pathology in most previous mid-trimester pregnancy loss, we did not exclude histological infection cases in the cervical insufficiency group because we could not know whether the infection occurred after cervical enlargement, or the infection induced preterm labor. Microorganisms causing these types of infections probably migrate to the uterus before or early during pregnancy [1]. We did not take routine vaginal cultures over this study period; however, vaginal cultures for bacterial vaginosis during the first trimester and the administration of appropriate treatment might have improved obstetric outcomes.

Women with mid-trimester pregnancy loss experience anxiety regarding the possibility of another pregnancy loss. In Japan, similar to many other developed countries, the interval between pregnancies has increased due to advanced maternal age. Detailed evaluation of any preceding pregnancy losses and informed decisions regarding the indication of prophylactic cerclage should be undertaken.

In conclusion, our data suggests that the history-indicated cerclage can be indicated for women with a single history of mid-trimester pregnancy loss with painless cervical dilation. Serial transvaginal ultrasound surveillance may reduce unnecessary cerclage, there are cases in which delayed intervention leads to premature delivery. Further prospective studies are expected to determine which cases are appropriate for the history-induced cerclage.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, AT, upon reasonable request.

AT, HT and TA designed the research study. AT and YI accumulated and analyzed the data. AT, HT, and TA wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of the Japanese Red Cross Nagoya Daiichi Hospital (2019-038). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study, the Ethical Committee approved that. This study adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki.

The authors thank the medical staff in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Japanese Red Cross Nagoya Daiichi Hospital.

This research was funded by Japanese Red Cross Aichi Medical Center Nagoya Daiichi Hospital Research Grant NFRCH 23-0024.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.