- Academic Editor

Sexual well-being is a vital aspect of the overall quality of life. Sexual self-efficacy is a key factor in improving of women’s sexual well-being. This study aimed to determine the effect of counseling based on functional analytic psychotherapy (FAP)-enhanced cognitive therapy (CT) on sexual self-efficacy in married adolescent women.

This prospective clinical trial, conducted in 2019, used a pre-test/post-test design with a control group. The study included 80 urban and rural married adolescents who met the inclusion criteria and were referred to the health centers in Darab and surrounding villages. Out of 350 participants, 150 adolescents were included in the study and were allocated to two groups. The counseling program for the intervention group was carried out by the researcher over 16 sessions, held twice a week for 90 minutes each. In contrast, the control group received routine education. The intervention group received counselling based on FAP-enhanced CT, while the control group did not receive this training during the study. The data collected from the questionnaires were imported into SPSS 24, and analyses were performed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), paired t-test, and independent t-test.

There was no significant difference in sexual self-efficacy between the two groups at pre-test time (p > 0.05); however, a significant difference was observed at post-test (p < 0.0001). Additionally, there was a significant difference between the mean scores of sexual self-efficacy before and after the intervention in the intervention group (p < 0.0001), while no significant difference was observed in the control group (p = 0.25).

The results suggest that counselling based on FAP-enhanced CT provided to married adolescent women significantly improves their sexual self-efficacy.

The trial protocol was registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials on 16/06/2019, IRCT20190217042736N1 (https://www.irct.ir/trial/37718).

Studies have reported a prevalence of sexual disorders ranging from 31% to 66% [1, 2]. In the United States (US), the prevalence of sexual disorders ranges from 10% to 52% in men and from 25% to 63% in women [3]. Problems with sexual desire are among the most prevalent sexual disorders affecting women in the US [4]. Moreover, the prevalence of sexual disorders in China has been reported to be 35% [5]. Few studies have been conducted on women’s sexual disorders in Iran [6]. Researchers have reported that 68.4% of women and 66.7% of men have complained about issues related to sexual function [7]. The results of another study indicated that 60% of men and 50% of women were dissatisfied with their sexual function, and among those dissatisfied, 50% ultimately divorced [8]. In Sari, it was reported that 21.9% of newly married women suffer from sexual disorders [9]. Another study found that 66% of the newly married women in Zanjan reported experiencing sexual disorders [1]. The concept of “self-efficacy”, a central component of Bandura’s social cognitive theory, refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to successfully perform a specific behavior. Within this framework, “sexual self-efficacy” is a subordinate construct that specifically addresses an individual’s confidence in their ability to effectively engage in and manage sexual behaviors [2]. Most sex therapists have observed that the evaluating sexual growth and development is essential for understanding sexual problems and determining their underlying nature. Moreover, an intervening variable known as sexual self-efficacy, along with an individual’s level of introversion or extroversion, plays a significant role in this context [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. However, the emotions resulting from efficacy and inefficacy can affect the enhancement or inhibition of sexual self-efficacy. Sexual problems and low self-efficacy often lead to anxiety, worry, depression, and low self-confidence, negatively impacting individual’s sexual relationships due to a heightened expectation of failure. All the aforementioned findings confirm the role of sexual self-efficacy as a key latent variable influencing sexual function [8, 9]. Age is one of the effective factors of sexual self-efficacy. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adolescence as the age range of 10–19 years, identifying this group as one of the most vital within society. The health of adolescents is crucial to public health [15]. Younger individuals, particularly adolescents, may have lower sexual self-efficacy due to limited sexual experience, evolving self-identity, and a lack of knowledge or education on sexual health. With age and increased life and sexual experiences, individuals may develop higher sexual self-efficacy, which can contribute to more informed and confident sexual decision-making [16].

The effects of interventions such as pelvic floor exercises, sex therapy, and cognitive therapy (CT) on sexual self-efficacy have been investigated in different studies, which indicate that these approaches can increase sexual self-efficacy [17, 18, 19]. Various types of psychotherapy and counseling can be employed in this context. One of the most effective approaches is counseling based on functional analytic psychotherapy (FAP)-enhanced CT, integrating both FAP and CT techniques simultaneously. This approach aims to enable cognitive-behavioral consultants to provide more effective treatment while creating deeper interpersonal relationships with their clients. The rationale for combining FAP with CT includes improving acceptance of the treatment’s underlying principles and addressing the limitations of CT. This treatment method consists of three steps. In the first step, the treatment rationale is explained, and the individual’s issues are assessed. The second, more critical step, involves generalizing targeted behaviors to the client’s routine live. The final step focuses on maintaining progress and ending the treatment [20, 21].

Jamali et al. (2017) [18] conducted a study aiming to examine the effects of a cognitive-behavioral intervention on sexual self-efficacy and marital satisfaction in 30 randomly selected women referred to psychological service centers in Kashan. The results indicated that cognitive-behavioral intervention ameliorates couples’ relationships by improving both sexual self-efficacy and marital satisfaction [18]. Etemadi et al. (2018) [19] also conducted a study to investigate the effects of FAP on depression, anxiety, and marital satisfaction in women experiencing marital distress. 30 women with symptoms of anxiety and depression, referred to the psychological clinic of the State Welfare Organization of Tabriz, were selected for this study. The results suggested that FAP reduced depression and anxiety, while increasing marital satisfaction [19]. Few studies have been conducted on sexual self-efficacy in Iran, and counseling based on FAP-enhanced CT has not yet been employed to adolescents. Various counseling methods have been used to address sexual issues; however, each method has its limitations. Counseling based on FAP-enhanced CT utilizes both approaches, allowing them to compensate each other’s weaknesses and amplify each other’s strengths. The current study aims to examine the effectiveness of an integrated counseling approach that combines FAP with enhanced cognitive therapy to improve sexual self-efficacy among married adolescent women. Given the significant impact of sexual self-efficacy on sexual function and overall well-being, particularly among younger individuals who may lack the experience and confidence in managing sexual behaviors, this study aims to address a critical gap in the literature. Previous research has demonstrated the benefits of CT and FAP individually; however, their combined use to address sexual self-efficacy, especially in adolescents, remains underexplored.

This prospective clinical trial, utilizing a pre-test and post-test design with a control group, was conducted in 2019 on urban and rural adolescents who met the inclusion criteria and were referred to health centers of Darab and nearby villages.

Initially, all urban and rural health centers in Darab (a total of 8 centers) were visited, and a list of married adolescents was compiled. Subsequently, the adolescents were contacted and informed about the study’s objectives. A list was created of those who expressed willingness to participate. Of these, 150 adolescents met the inclusion criteria, with 75 people assigned to each group. Although the sample size could have been smaller considering the anticipated attrition rate, we decided to include all of the eligible individuals due to the high number of sessions involved.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: being Iranian, residing in Darab, being literate, free from chronic diseases and diagnosed psychological disorders, no stressful events in the past month, aged 15–19 years old, being married for at least one year, in a monogamous marriage, no extramarital relationships, cohabitating with their husband, not being pregnant, no history of genital surgery, neither spouse not being addicted to the narcotics or alcohol, neither spouse using medications that affect sexual function, engaging in sexual intercourse at least once a week, at least one year since any previous childbirth, no diagnosed sexual issues in the spouse, being officially married, being a Muslim of Shia faith [17, 22, 23].

The exclusion criteria included: suffering from severe or chronic diseases during the study, having diagnosed psychological disorders during the study, unwillingness to continue participation, taking any psychiatric medication or psychedelic drugs, receiving any other type of psychological services, and failing two or more counseling sessions [17].

The intervention group received counselling based on FAP-enhanced CT, designed to improve sexual self-efficacy among married adolescent women. This integrated approach was tailored to address both the psychological and behavioral aspects of sexual self-efficacy, providing personalized therapy sessions that focused on real-time feedback and experiential learning. In contrast, the control group received routine education which consisted of standard informational sessions on sexual health and relationships. These sessions were less interactive and did not include the personalized therapeutic elements offered to the intervention group.

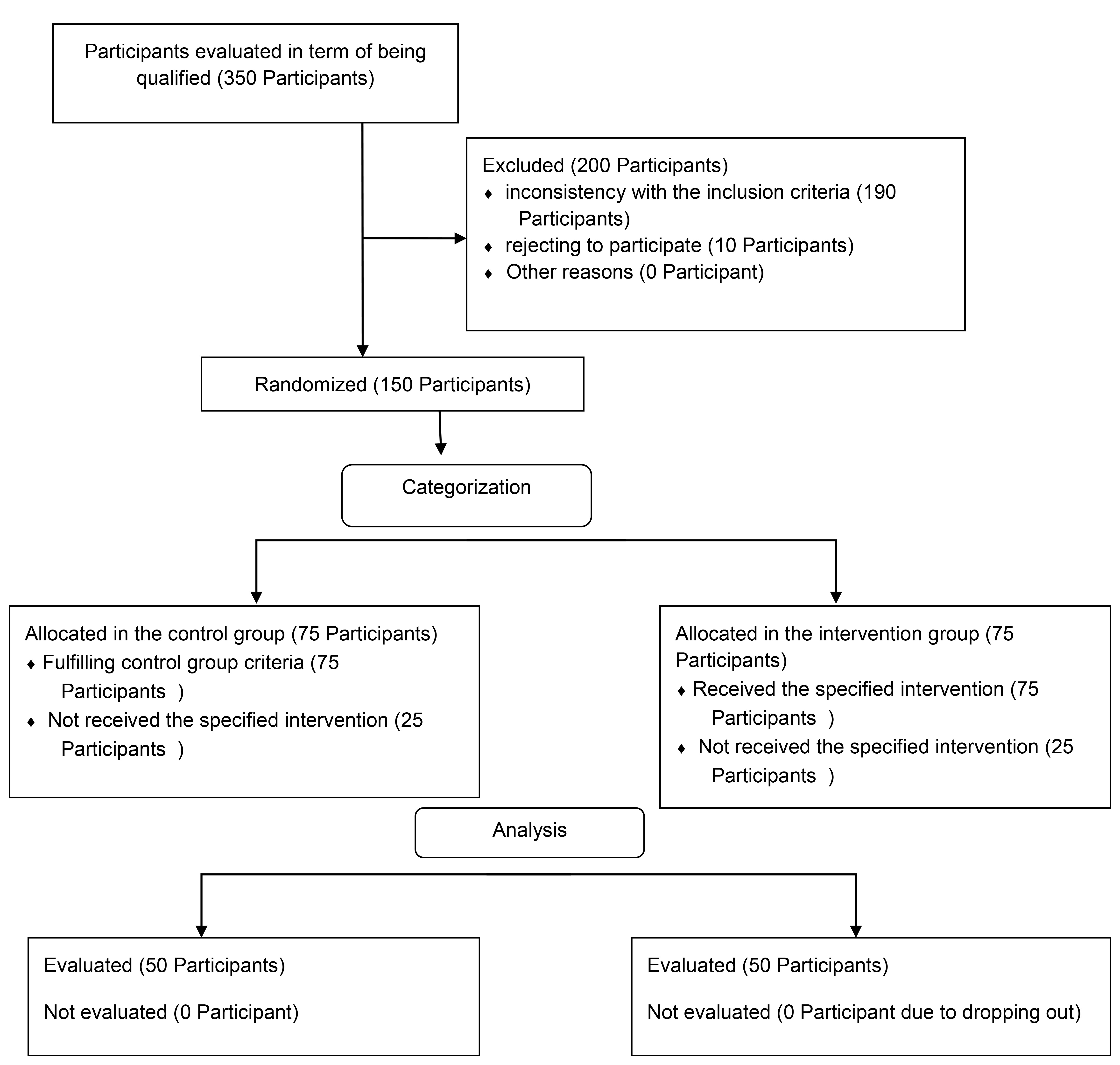

Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group using the permutation block method, with random allocation. Dark-colored envelopes were employed to conceal group allocations, ensuring that both participants and researchers remained blinded to the assignment. This method ensured that the intervention and control groups were clearly defined and comparable at the start of the study (Fig. 1 shows the flow diagram of the study), with 50 females in each group at the conclusion of the study.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Due to limitations in the intervention methods, we were unable to blind the participants and researchers. However, to reduce the risk of bias, the statistician was blinded to group assignments. For this purpose, the study groups were labeled as A and B for the statistician.

Sampling was performed over a three-month period in 2020. In the intervention group, counselling based on FAP-enhanced CT was carried out by the researcher over 16 sessions, twice a week for 90 minutes, over 14 consecutive weeks. The 15th and 16th sessions were held at a two-week interval [23].

Simultaneously with the intervention group, pre-test and post-test assessments were conducted in the control group at the beginning and end of the study. To adhere to ethical principles, a pamphlet summarizing of the content provided to the intervention group was given to the control group after they had completed the post-test. The content of the sessions is outlined in Table 1, obtained from similar sources [20].

| Session | Objectives |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to the sessions, establishing communication, explaining the counseling objectives, emphasizing confidentiality, raising awareness (including the definition of the sexual response cycle and the benefits of sexual intercourse), and assigning homework |

| 2 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, explaining the counseling method, discussing attachment in the 16 sessions, focusing on the participants’ perceptions of the therapist’s reactions (with the client expressing her marital problems to the therapist), explaining emotions (such as frustration, disappointment, depression, anxiety, and worry), discussing sexual life and self-efficacy, assigning homework, and reinforcing the confidentiality of the content |

| 3 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, explaining women’s sexual and psychological disorders, discussing the impact of ethics and law on sexual quality and self-efficacy, role-play, assigning homework, stressing the confidentiality of the content |

| 4 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, explaining the sexual role, physical attraction, sexual self-confidence, role-play, assigning homework, and stressing the confidentiality of the contents |

| 5 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, explaining sexual identity and factors affecting it, role-play, homework, stressing the confidentiality of the contents |

| 6 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, explaining sex and sexual desires, assigning homework, stressing the confidentiality of the contents |

| 7 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, efficient espousal communication skills, behaviors leading to spousal relationship self-efficacy, the effect of addiction on sexual relationships, assigning homework, stressing the confidentiality of the contents |

| 8 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, the quality of men’s sexual life (intensive), men’s sexual disorders, assigning homework, stressing the confidentiality of the contents |

| 9 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, self-efficacy and factors affecting it (sexual goals, self-confidence, self-esteem, sexual goals), general self-efficacy, assigning homework, stressing the confidentiality of the contents |

| 10 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, encouraging to express emotions, explaining sexual and relationship satisfaction (pleasure, self-directed positive feeling, sexual intimacy, sexual issues, and the quality of relationships), assigning homework, stressing the confidentiality of the contents |

| 11 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, the difference between attachment and love, explaining the value of self (feminine efficacy, sexual self-confidence, feeling of guilt toward the sexual life), assigning homework, stressing the confidentiality of the contents |

| 12 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, the antecedent-behavior-consequence (ABC) triangle, explaining sexual repression (pleasure, sexual mistakes related to cultures and values, avoidance, despair), assigning homework, stressing the confidentiality of the contents |

| 13 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, explaining sexual initiative and competence, unexpected issues, methods for sexual variety, assigning homework, stressing the confidentiality of the contents |

| 14 | Introducing the mindfulness technique, interpreting the variables affecting the clients’ behavior in role-play, assigning homework, stressing the confidentiality of the contents |

| 15 | Maintenance session, reviewing the practical techniques, assigning homework, stressing the confidentiality of the contents |

Participants completed a demographic information questionnaire and sexual self-efficacy questionnaire.

1. The demographic questionnaire included gender, age, duration of the marriage, spouse’s age, occupation, spouse’s occupation, number of children, education level, and spouse’s education level.

2. This questionnaire was adapted from the sexual self-efficacy questionnaire [24]. It consists of 9 questions, each scored on a 3-point Likert scale: “Always” (score of 100), “Sometimes” (score of 50), and “Never” (score of 0). The lowest possible score was 0, and the highest possible score was 100, and the total score was divided by 9. Scores below the mean indicated lower levels of sexual self-efficacy and were considered less desirable. It was sent to 10 professors of midwifery and gynecology, as wells as psychology consultants, to check its validity. After obtaining the ethics approval, 23 questionnaires were completed by married women to check the reliability. The results showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95, indicating strong internal consistency. To assess repeatability through a retest, the questionnaires were completed by the same individuals after one week. The results showed an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) index of 0.91, demonstrating high repeatability.

Primary outcome: sexual self-efficacy of married adolescent women.

Secondary outcome: none.

Sample size calculations were conducted based on similar study [24]. The power and significance level were considered to be 80% and 0.05, respectively. Using the following formula, the required sample size was calculated to be 80. To account for drop out rate, 20% was added to the sample size.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM

Corp., Chicago, IL, USA). To compare the intervention and control groups after

the intervention, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used. Due to the normality

of the data, the independent sample t-test was used to compare the two

groups before the intervention. The Chi-square (

Fig. 1 shows the flow diagram of the study. Of the 350 adolescents, 150 were included and randomly allocated to two groups, with each group consisting of 75 females.

This study started at 20/9/2019, and last for one year. Table 2 shows the mean

age of the participants and the mean age of their spouses in both groups.

Considering the parametric conditions, the independent sample t-test

revealed no significant difference between the two groups in terms of age and

spouse’s age (p

| Variable Group | Intervention (n = 50) | Control (n = 50) | t-value | p-value | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Age (years) | 17.62 | 1.32 | 17.38 | 1.15 | 0.96 | 0.33 |

| Spouse age (years) | 27.56 | 3.43 | 26.56 | 3.02 | 1.54 | 0.12 |

SD, standard deviation.

| Variable Group | Intervention (n = 50) | Control (n = 50) | p-value | χ2 | |||

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | ||||

| Education level | |||||||

| Primary high school | 7 | 14 | 6 | 12 | 0.85 | 0.31 | |

| Secondary high school | 35 | 70 | 34 | 68 | |||

| University student | 8 | 16 | 10 | 20 | |||

| Spouse’s education level | |||||||

| Illiterate | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.70* | - | |

| Primary school | 6 | 12 | 4 | 8 | |||

| High school diploma | 20 | 40 | 20 | 40 | |||

| Associate’s degree | 10 | 20 | 11 | 22 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 12 | 24 | 15 | 30 | |||

| Spouse’s job | |||||||

| Unemployed | 5 | 10 | 3 | 6 | 0.60 | 0.89 | |

| Worker | 5 | 10 | 6 | 12 | |||

| Self-employed | 30 | 60 | 31 | 62 | |||

| Clerk | 10 | 20 | 10 | 20 | |||

| Number of children | |||||||

| 0 | 27 | 54 | 39 | 78 | 0.04* | - | |

| 1 | 15 | 30 | 9 | 18 | |||

| 2 | 7 | 14 | 2 | 4 | |||

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

*Fisher’s exact test.

The independent sample t-test showed no significant difference between

the intervention (49.33

| Variable Group | Intervention (n = 50) | Control (n = 50) | Comparison between two groups after the intervention | ||

| Mean |

Mean |

Mean difference (95% CI) | F** | p-value | |

| Sexual self-efficacy (pre-test) | 49.33 |

52.66 |

34.39 (30.90, 37.80) | 386.33 | p |

| Sexual self-efficacy (post-test) | 86.22 |

53.66 | |||

| p-value* | p |

0.25* | |||

| Paired t statistic | 14.70 | 1.15 | |||

*Paired t-test, **ANCOVA.

SD, standard deviation; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ANCOVA, analysis of covariance.

This study showed counselling based on FAP-enhanced CT could improve sexual self-efficacy in married adolescent women. Several studies examined sexual self-efficacy worldwide, but the present study focused on a specific population—married adolescent women—using counselling based on FAP-enhanced CT.

In this study, there was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups in terms of the participants age and the spouse’s age. However, a significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of the number of children, and this variable was controlled for in the ANCOVA. No significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of education level, spouse’s education level, occupation, and spouse’s occupation, indicating consistency between the two groups. This indicates that the samples in both groups were consistent in terms of both quantitative and qualitative variables. The results indicated no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the mean scores of sexual self-efficacy scores before the intervention. However, the results revealed a significant difference between the two groups in terms of the mean sexual self-efficacy scores after the intervention.

The findings of a study on sexual self-efficacy in women with breast cancer [2] were concurrent with those of the present study. Similarly, quality-of-life therapy improved sexual self-efficacy and marital satisfaction in couples affected by addiction [20]. The study conducted by Vandenberghe et al. (2010) [21] , which aimed to assess the impact of couples therapy on female orgasmic disorder, suggested that FAP could be an effective approach. The present study utilized a combination of cognitive-behavioral counseling and FAP, with each approach complementing the other’s weaknesses and enhancing their overall effectiveness.

A study titled “The effect of counseling based on Bandura’s self-efficacy theory on sexual self-efficacy and quality of sexual life” reported the efficacy of the intervention [25]. Moreover, cognitive-behavioral intervention has been shown to enhance couples’ relationships by improving sexual self-efficacy and marital satisfaction [13], as well as increasing pregnant women’s sexual function, satisfaction, and self-efficacy [26]. In addition, sex therapy improved the diabetic women’s sexual self-efficacy [22]. A study titled “Effectiveness of quality-of-life therapy on sexual self-efficacy and quality of life in addicted couples” reported that the intervention significantly improved the quality of life and sexual self-efficacy among the addicted couples during the treatment period in Qazvin [27].

Kegel’s exercise improved women’s sexual self-efficacy both immediately after delivery and 8 weeks later [28]. Steinke et al. (2013) [23] conducted a study to determine the effect of a sexual counseling intervention based on social-cognitive theory on sexual satisfaction, sexual self-efficacy, awareness, return to sexual activity, sexual anxiety, sexual depression, and various dimensions of quality of life. The results indicated that sexual anxiety did not change after the intervention, and sexual self-efficacy remained at the same average level. Additionally, there was no significant difference in sexual worry before and after the intervention [23]. The results of this study were not consistent with those of the present study, which may be due to differences in the type of counseling, follow-up duration, and sample size. In the present study, the sample size was significantly larger, and participants received more counseling sessions and follow-up support.

Sexual self-efficacy is multidimensional factor that refers to an individual’s perception of their ability to express sexual behaviors, their desirability to a sexual partner, and their confidence and self-efficacy in sexual behaviors. Sexual self-efficacy is crucial to perform in efficient sexual activity. High sexual self-efficacy improves psychological well-being and social functioning. In fact, sexual self-efficacy is a predictor of sexual activity [22].

These findings align with previous research on various therapeutic interventions, highlighting the importance of addressing psychological and cognitive factors in enhancing sexual self-efficacy. The unique contribution of this study lies in its focus on a specific, vulnerable population, and the use of a novel integrated counseling approach that addresses the limitations of traditional methods. However, it is important to acknowledge potential limitations, such as the cultural context of the participants and the reliance on self-reported data, which may influence the generalizability of the findings. Future research should consider exploring this approach in different populations and settings, as well as incorporating longer follow-up periods to assess the sustainability of the intervention’s effects. Overall, the results underscore the critical role of targeted psychological interventions in improving sexual self-efficacy, consequently, sexual health and well-being.

This study was conducted in a city in Iran with a high rate of teenage marriage. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings should be approached with caution. Encouraging participants to attend all sessions was one of the major challenges. To overcome this challenge, the counsellor explained the benefits of participation both before the study and throughout each session.

The findings revealed that FAP-enhanced CT counseling for married adolescent women can significantly improve their sexual self-efficacy.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

MG, KA: design of the work, write the main manuscript; MT: acquisition, analysis of data for the work, write the main manuscript; AA: study conception and design; YJ: data analysis. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. To observe the ethical considerations, in addition to receiving informed consent letters, ethics code from Kerman University of Medical Sciences (IR.KMU.REC.1398.091) and clinical trial code (IRCT20190217042736N1) with registration date of 16/06/2019 were obtained. Shiraz University of Medical Sciences permission and informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). Participants could easily withdraw from the study whenever they were willing. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (declaration of Helsinki).

Thanks a lot, from Kerman university of medical sciences to support this research as well as all of the women who participated in this study.

Kerman university of medical sciences (grant number: 97000905).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.