Background: To describe the fine ultrasonic diagnostic criteria and clinical management of different types of singleton angular pregnancy. Methods: Sixty cases of angular pregnancy were collected in a single Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology from January 2016 to July 2020. The general medical history, ultrasonic images, pregnancy outcomes, surgical records, clinical management, pathological examination results and postoperative ultrasound images were collected to analyze the related risk factors, clinical manifestation, fine ultrasonic diagnostic criteria, clinical management, outcomes, and complications. Results: Among the 60 cases, 46 cases (76.7%) had related risk factors and 14 (23.3%) did not. Twenty-five cases (41.6%) had clinical symptoms of vaginal bleeding with or without lower abdominal pain and 35 cases (58.4%) had no symptoms of an abnormal pregnancy. Fifty-nine cases (98.3%) were diagnosed as different types of angular pregnancy. The number of cases of type I, II and III angular pregnancy cases was 42 (71.2%), 13 (22.0%) and 4 (6.8%), according to the gold standard diagnosis of our research. Ultrasound sensitivity in the diagnosis of type I, II and III angular pregnancy in the first trimester was 83.3%, 69.2% and 50.0%. Fifty-six cases (93.3%) resulted in a favorable outcome, while 4 cases (6.7%) showed complications. Conclusions: The different types of angular pregnancy have variable pregnancy outcomes and risks requiring clinical management to be individualized. Fine ultrasonic diagnosis is both crucial and feasible.

There exists wide-ranging debate over definitions of pregnancies located at the utero-tubal junction (angular, cornual, and the eccentric pregnancy) [1, 2, 3]. We adopted Williams’ most current version [4], defining a cornual pregnancy as “a conception that develops in the rudimentary horn of a uterus with a Mullerian anomaly”. Combining the literature [3, 5, 6, 7] with our clinical experience, we propose the term angular pregnancy to designate implantation of the embryo just medial to the utero-tubal junction at the lateral angle of the uterine cavity and inside of the round ligament.

We further propose a fine classification of angular pregnancy, dividing it into

three types according to the location of implantation of the embryo and growing

direction. Type I (endogenic type) is defined as implantation of the embryo

partly in the uterine angular and mostly (

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.The schematic diagrams and ultrasound image of virtual dividing lines and partitions of uterine cavity. Schematic diagrams: (A) Coronal view of uterus and adnexa. (B) Virtual dividing lines of uterine cavity. (C) Virtual partitions of uterine cavity. (E) The implantation sites of three types of angular pregnancy and tubal interstitial pregnancy (The black oval is the pregnancy sac.). Ultrasound render image: (D) Uterine coronal three-dimensional ultrasound render image, virtual dividing lines, and virtual partitions of uterine cavity.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Schematic diagrams of definitions and gold standard diagnostic criteria of three different types of angular pregnancy and tubal interstitial pregnancy (The short-dotted line is angle and central dividing line; the long-dotted line is angle and tubal interstitial dividing line; the black oval is the pregnancy sac.). Schematic diagrams: (A) Type I angular pregnancy (endogenic type). (B) Type II angular pregnancy (exogenous type). (C) Type III angular pregnancy (angular and interstitial type). (D) Tubal interstitial pregnancy.

Angular pregnancy constitutes a high-risk pregnancy. If angular pregnancy is not diagnosed in the first trimester, it is more likely to be missed during the second and third trimesters. Angular rupture and massive hemorrhage may occur either prior to or during delivery, endangering the lives of the pregnant patient and her fetus. If prenatal diagnosis is missed, angular placenta implantation with uterine wall penetration may occur, resulting in obstetric complications such as postpartum hemorrhage and/or infection secondary to retained placental material.

The purpose of this study is to describe the related risk factors, clinical manifestation, ultrasonic diagnostic criteria, clinical management, outcomes, and complications of different types of uterine angular pregnancy.

This study is a retrospective and descriptive analysis of the data collected in routine pregnancy care. The cases feature patients with angular pregnancy who were treated in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Tongji Hospital affiliated with Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology from January 2016 to July 2020. Inclusion criteria entailed the diagnosis of an angular pregnancy in early pregnancy by ultrasonic examination; the diagnosis of a normal early intrauterine pregnancy followed by the ultrasonic diagnosis of an angular pregnancy or angular placenta accrete during the middle or late pregnancy; or diagnosis postpartum by ultrasound of an angular pregnancy with portions of a retained placenta. Exclusion criteria entailed cases of angular pregnancy diagnosed by ultrasound in our institution but not observed, treated, or delivered in our hospital; malformed uterine anatomy; multiple gestation; or cases with absence of complete ultrasonic data.

Diagnosis made by direct vision, postoperative pathological examination or

clinical comprehensive diagnosis is regarded as the gold standard of our research

and the gold standard of our center’s clinical practice. Angular pregnancy has

been divided into three types (See Fig. 2A–C): type I (endogenic type) with no

or mild angular protrusion, wherein the majority (

Type I angular pregnancy should be differentiated from normal intrauterine pregnancy, in which the GS is found in the endometrium of the body or fundus of the uterus without the diagnostic criteria of angular pregnancy at the time of surgery, delivery, or pathological examination of angular pregnancy. Type II and III angular pregnancy should be differentiated from tubal interstitial pregnancy. In tubal interstitial pregnancy, the pregnancy mass is found in the interstitial part of the fallopian tube outside of the round ligament, with villi seen in the interstitial portion of fallopian tube by direct vision of surgery and postoperative pathological examination (Fig. 2D). The surgical site of type II angular pregnancy is the angular, the surgical site of type III angular pregnancy is the angular and fallopian tube, and the surgical site of tubal interstitial pregnancy is the fallopian tube.

During the ultrasound examination in the first trimester, our system recorded ultrasound images and reports that included the location of the gestational sac, whether the gestational sac is continuous with the endometrium at the fundus of the uterus, the presence of decidual wrapping sign, the presence of interstitial line sign [8, 9], the minimum thickness of the muscle wall from the outermost edge of the gestational sac to the serous layer at the angular, degree of protrusion of the gestational sac, boundary between the villi and the muscle wall of the gestational sac, and blood flow at the implantation site. If the gestational sac were located near the utero-tubal junction, a diagnosis of angular pregnancy was made and divided into three types according to the ultrasonic characteristics.

The ultrasonic diagnostic criteria of type I angular pregnancy include: (1) the

vast majority (

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.The uterine coronal three-dimensional ultrasound render images of three types of angular pregnancy and tubal interstitial pregnancy (GS, gestational sac; EN, Endometrium; M, mass). (A) Type I angular pregnancy (Dotted line indicates O-shaped decidua wrapping sign). (B) Type II angular pregnancy (Dotted line indicates O-shaped decidua wrapping sign). (C) Type III angular pregnancy (Dotted line indicates C-shaped decidua wrapping sign). (D) Tubal interstitial pregnancy (Dotted line indicates interstitial line sign).

Type I angular pregnancy should be differentiated from normal intrauterine pregnancy in which the GS is located in the endometrium of the body or fundus of the uterus without the ultrasonic diagnostic criteria in the first trimester. Type II and III angular pregnancy should be differentiated from tubal interstitial pregnancy. The ultrasonic diagnostic criteria of tubal interstitial pregnancy include: (1) the GS is located in the interstitial part of the fallopian tube; (2) the inner side of the GS is not continuous with the decidua; (3) with interstitial line sign; (4) the pregnancy mass is located in the interstitial part of the fallopian tube (Fig. 3D).

During the ultrasound examination in the second and third trimesters, the thickness of angular muscle wall, degree of protrusion and presence or absence of placenta accrete were recorded in cases of type I angular pregnancy. The residual placenta or villi and implantation at the angular site were recorded after delivery. The ultrasound scan was obtained by combined use of two-dimensional ultrasound, three-dimensional ultrasound, color Doppler and spectral Doppler. Measurement of the data was carried out on the two-dimensional image, while the three-dimensional image directly pinpointed the position of the pregnancy sac.

The statistical software package SPSS26.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, 26.0 version, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data analysis. The data of classified variables are represented by n (%) with the results of data analysis being shown by bar chart and the data of continuous variables being represented by M (25%–75%).

A total of 60 cases were included in this study. The median age of pregnant women was 30 years (29–34), the median clinical gestational week was 7.5 weeks (7.0–8.9), and the median ultrasound gestational week was 6.5 weeks (5.8–7.8). The frequency and percentage of related clinical characteristics of cases are shown in Table 1. Among the 60 cases, 46 cases (76.7%) had related risk factors and 14 cases (23.3%) did not. Twenty-five cases (41.6%) had clinical symptoms of vaginal bleeding with or without lower abdominal pain and 35 cases (58.4%) had no symptoms of an abnormal pregnancy.

| Clinical characteristics | n (%) | |

| Gravidity and parity, pregnancy history | ||

| Primigravid | 24 (40.0%) | |

| Vaginal delivery | 15 (25.0%) | |

| Cesarean section | 8 (13.4%) | |

| Induced labor | 2 (3.3%) | |

| Placental abruption | 2 (3.3%) | |

| Abortion | 22 (36.7%) | |

| Villus or retained placenta | 2 (3.3%) | |

| Ectopic pregnancy | 4 (6.7%) | |

| Salpingectomy | 3 (5.0%) | |

| History of uterine surgery or uterine complications | ||

| Removal of endometrial polyps | 2 (3.3%) | |

| Lysis of uterine adhesions | 2 (3.3%) | |

| Adhesive band in the uterine cavity | 4 (6.7%) | |

| Uterine leiomyoma or adenomyoma | 11 (18.3%) | |

| Mode of conception | ||

| Natural conception | 48 (80.3%) | |

| ART | 12 (20.3%) | |

| First pregnancy conceived naturally without any history of surgery or uterine complications | 14 (23.3%) | |

| Clinical symptoms | ||

| Vaginal bleeding | 17 (28.3%) | |

| Lower abdominal pain | 8 (13.3%) | |

| Without any symptoms | 35 (58.4%) | |

| ART, assisted reproductive technology. | ||

The ultrasonic diagnosis, clinical management, complication, pregnancy outcome and gold standard diagnosis of 60 cases are shown in Table 2. Among the 60 cases, 59 (98.3%) were diagnosed as different types of angular pregnancy according to the established gold criteria. The number of cases of type I, II and III angular pregnancies was 42 (71.2%), 13 (22.0%) and 4 (6.8%), respectively. The percentage of angular villi or placental accrete in type I, II and III angular pregnancy was 4.8% (2/42), 23.1% (3/13) and 100% (4/4). Seventy-five percent (3/4) of type III angular pregnancies had angular rupture with villi or placental tissue protruding outward.

| FTS (60, 100%) | Clinical management, outcome, and complication | GSD | |

| I (42, 71.2%) | |||

| II (13, 22.0%) | |||

| III (4, 6.8%) | |||

| Interstitial (1, 1.7%) | |||

| normal IUP (4, 6.7%) | Expectant (2, 3.3%) | US at 32wks PP in the right angular, CD, PP in the right angular, MAP (1, 1.7%) (See Fig. 5) | I with PA (1, 1.7%) |

| At 15 wks. US: right angular protruding; at 20wks, right lower abdominal pain, US: right angular and interstitial pregnancy, PA, right angular rupture. Emergency laparotomy, two lacerations and PA in the right angular, angular incision to take the dead fetus, salpingectomy + angular wedge resection + angular + angular plastic surgery (1, 1.7%) (See Fig. 6) | III with PA (1, 1.7%) | ||

| Ask for termination (2, 3.3%) | Negative pressure uterine aspiration under UC, tissue residue in the angular, hysteroscopic tissue removal under UC (2, 3.3%) | I (2, 3.3%) | |

| Type I AP (35, 58.3%) | Expectant (14, 23.3%) | Live birth without complications (8, 13.3%) | I (8, 13.3%) |

| Live birth, angular placenta residue and PA (1, 1.7%) | I with PA (1, 1.7%) | ||

| MA + UC (5, 8.3%) | I (5, 8.3%) | ||

| Ask for termination (21, 35.0%) | Negative pressure uterine aspiration under UM (14, 23.3%) | I (14, 23.3%) | |

| MA + UC (3, 5.0%) | I (3, 5.0%) | ||

| MA (2, 3.3%) | I (2, 3.3%) | ||

| Hysteroscopic embryo extraction under UM (2, 3.3%) | I (2, 3.3%) | ||

| Type II AP (13, 21.7%) | Expectant (3, 5.0%) | The embryo stops developing or spontaneous abortion, hysteroscopic embryo extraction under UM (3, 5.0%) | I (1, 1.7%) |

| II (2, 3.3%) | |||

| Elective surgery (10, 16.7%) | Negative pressure uterine aspiration under UM (4, 6.7%) | II (4, 6.7%) | |

| Removal of pregnant tissue by laparoscopic hysteroscopy combined under UM (6, 10%) | I (3, 5.0%) | ||

| II (3, 5.0%) | |||

| Type III AP (3, 5.0%) | Elective surgery (2, 3.3%) | Lower abdominal pain, laparoscopic salpingectomy + angular wedge resection + angular plastic surgery (1, 1.7%) | III with VA (1, 1.7%) |

| Laparoscopic resection of tubal interstitial pregnancy (1, 1.7%) | Interstitial (1, 1.7%) | ||

| with VA (1, 1.7%) | Emergency operation (1, 1.7%) | Lower abdominal pain, angular rupture, pregnancy tissue removal + salpingectomy + angular plastic surgery (1, 1.7%) | III with VA (1, 1.7%) |

| Interstitial pregnancy (5, 8.3%) | Emergency operation (5, 8.3%) | Lower abdominal pain, laparoscopic resection of angular pregnancy (4, 6.7%) | II (4, 6.7%) |

| with VA (4, 6.7%) | with VA (3, 5.0%) | ||

| Lower abdominal pain, angular rupture, laparotomy pregnancy tissue removal + salpingectomy + angular plastic surgery (1, 1.7%) | III with VA (1, 1.7%) | ||

| FTS, first-trimester screen; GSD, Gold standard diagnosis; US, Ultrasound; UM, ultrasound monitoring; PA, placenta accrete; PP, placental penetration; VA, villi accrete; IUP, intrauterine pregnancy; CD, cesarean delivery; MAP, manual abruption of placenta; AP, angular pregnancy; MA, medical abortion; UC, uterine curettage; wks, Weeks. | |||

The sensitivity of ultrasound in the first trimester diagnosis of type I, II and III angular pregnancy was 83.3% (35/42), 69.2% (9/13) and 50.0% (2/4). The sensitivity of ultrasound was calculated according to the ultrasonic diagnosis of early pregnancy in the first column vs. the gold standard diagnosis in the last column of Table 2. Because there were no true negative or false positive cases in this study, the diagnostic specificity is not calculated.

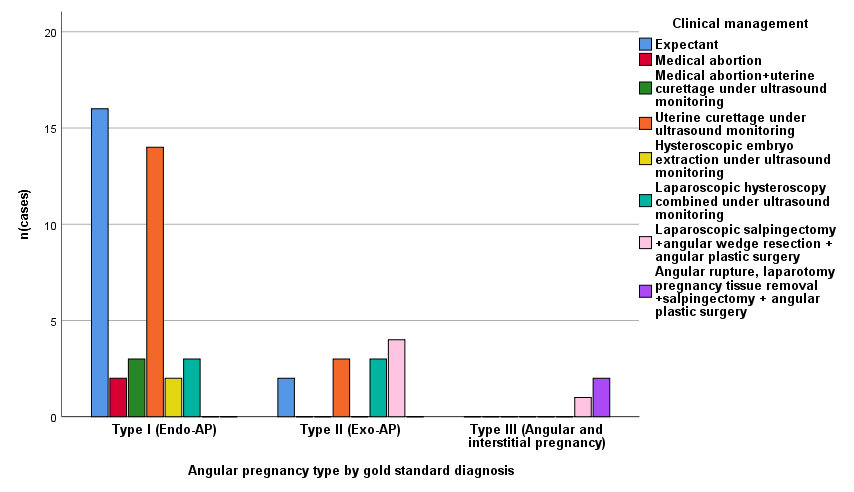

Frequencies of different clinical management without complications of various types of angular pregnancy based on the gold standard diagnosis are shown in Fig. 4. This analysis removed four cases of angular pregnancy with complications that included uterine rupture, inappropriate surgical methods or delivery mode resulting in residual villi or placental fragments in the angular region.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Frequencies of different clinical management without complications of various types of angular pregnancy based on the gold standard diagnosis (n = 55).

Among the 60 cases, 59 cases (98.3%) were diagnosed as different types of angular pregnancy according to the established gold criteria. Different cases presented different risk factors, while varying types of angular pregnancy entailed different clinical manifestations, pregnancy outcomes and risks. Fine ultrasonic diagnosis proved to be feasible and of critical value. Clinical management of the different types of angular pregnancy require individualization. Correct clinical treatment and good clinical results were obtained in 55 cases. Complications occurred in 4 cases.

Studies have found that history of abortion, pelvic surgery, cesarean section, assisted reproductive technologies, pathological changes of the fallopian tube, endometriosis and luteal deficiency are all related risk factors [10, 11]. Our study found that previous history of delivery, manual abruption of uterine angular placenta, abortion, villi residual in angular region after surgical abortion, placenta residual in the angular region postpartum, ectopic pregnancy, salpingectomy, uterine angular operation, uterine cavity adhesion, assisted reproductive technologies, uterine leiomyoma and adenomyosis may be related risk factors for an angular pregnancy.

The clinical manifestations of patients with an angular pregnancy include the absence of regular menstrual cycles with or without non-specific symptoms of vaginal bleeding, along with severe abdominal pain. Hemorrhagic shock may occur when the angular pregnancy ruptures, but most patients remain asymptomatic [3]. Angular pregnancy with placental accrete has no specific clinical symptoms but the placenta remains in the angular location during delivery and cannot be delivered naturally. Angular pregnancy with villi or placental implantation into the surrounding tissue has a higher risk of angular rupture.

In 1981, Janson et al. [7] put forward the following clinical diagnostic criteria for an angular pregnancy: (1) clinical pre sentation with painful asymmetric enlargement of the uterus; (2) directly observed (i.e., surgical) lateral distension of the uterus with displacement of the round ligament laterally; (3) retention of the placenta in the uterine angle. Angular pregnancy can be diagnosed in accordance with any of these criteria. The standard is clinical diagnosis based on gynecological examination and operative findings.

With the development of advanced medical imaging technology, current diagnostic methods for angular pregnancy include imaging diagnosis, laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, and laparotomy. Three-dimensional ultrasound is the first choice for the diagnosis of angular pregnancy with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), feasible if necessary [12]. During the ultrasound examination in the first trimester, it is crucial to describe with accuracy the location of the gestational sac in the utero-tubal junction and to identify the fine type of an angular pregnancy in order to evaluate the risk of pregnancy and to formulate a customized management plan.

As the different types of angular pregnancy have varied pregnancy outcomes, clinicians should make personalized management plans accordingly.

Type I angular pregnancy grows toward the center of the uterine cavity, as reported by Fernandez et al. [13]. With a continuing pregnancy, some will result in a live birth, but there exists a high risk of miscarriage, rupture of uterine angular, placenta accrete and retained placenta. As the pregnancy progresses, the clinician should regularly monitor the degree of angular protrusion, the thickness of the muscle wall, the location of the placental attachment and whether there is evidence of placenta accrete. When a pregnant woman with type I angular pregnancy requests termination of pregnancy, negative pressure suction or drug abortion can be utilized as the majority of the gestational sac is in the uterine cavity. It is recommended to perform fixed-point clearance negative pressure aspiration under ultrasound or intrauterine visual system guidance and, if necessary, to visualize the uterus by laparoscopy (Fig. 4). Mollo et al. [14, 15] put forward that hysteroscopic intact removal of angular pregnancies may be used as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool for angular pregnancy, providing a unique image of the intact removal of the gestational sac and allowing a markedly less invasive approach. Our clinical practice supports this view.

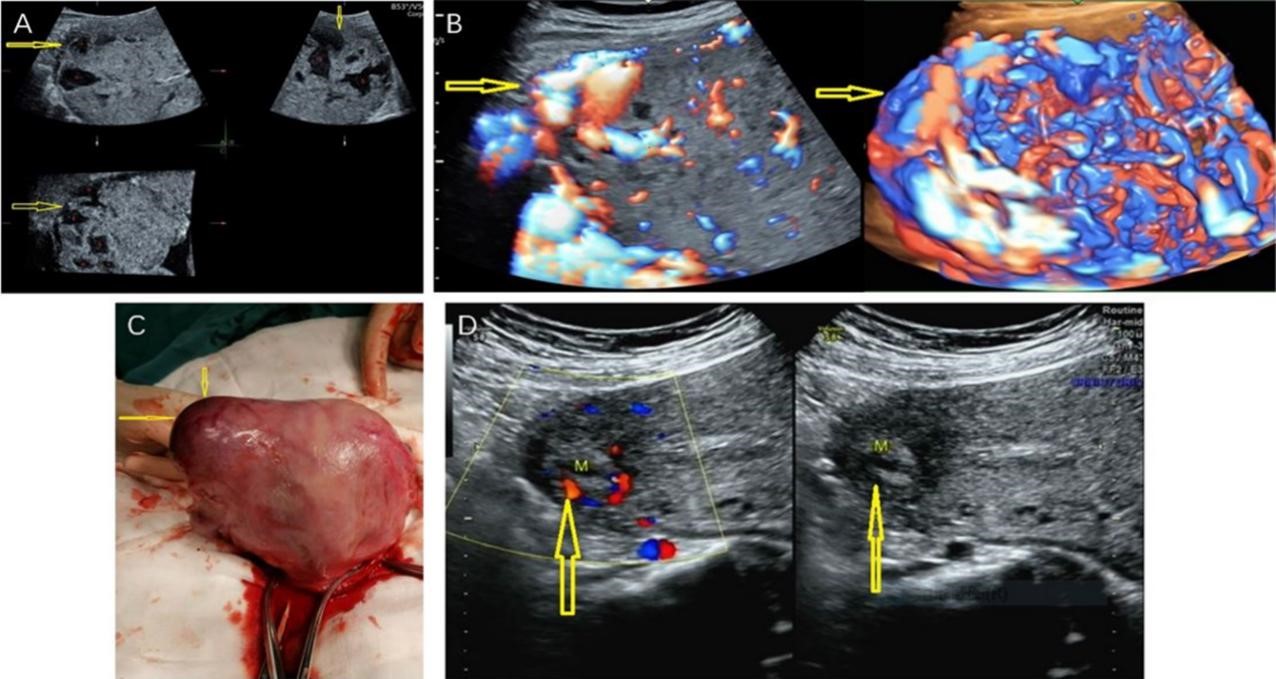

In our study, a 31-year-old pregnant woman with a type I angular pregnancy had a

previous live vaginal delivery 10 years prior without complications or other

surgical history. She was diagnosed as having a normal intrauterine pregnancy

during the first and second trimesters at another hospital. At 32 weeks

gestation, ultrasound determined that the fetus had hydrocephalus and placental

penetration at the uterine angular (Fig. 5A,B). The MRI scan confirmed the

ultrasound examination findings. After informing the patient of these findings,

she requested an induction of labor. Potassium chloride was injected into the

fetal heart under ultrasound guidance and a stillborn fetus was delivered by a

low transverse cesarean section. The placenta and fetal membranes were manually

removed. The right uterine angular demonstrated a 50.0 mm

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.The ultrasound images and intraoperative photos of a case of

type I angular pregnancy with placental penetration in the right angular. (A)

Multiplanar display of three-dimensional ultrasound at 32 weeks gestation. The

right uterine angular was slightly protruding; the thickness of the uterine

angular myometrium is 0 mm; the placenta is attached to the right angular, the

right wall and the upper right posterior wall; and there was no boundary between

the placenta and the muscle wall. Placental thickening with multiple lacunae and

eddy current is noted (The yellow arrow indicates the disappearance of the

normal muscle wall in the right angular with the placental tissue reaching the

serosal layer and the red pentagram indicates multiple lacunae in the placenta).

(B) Three-dimensional HD-Flow at 32 weeks of gestation (There are abundant and

messy blood flow signals in the placenta and under the serosa of the placenta

with the yellow arrow indicating that the type of blood flow in the right angular

overflows the serosa). (C) A photo of uterus during low transverse uterine

segment cesarean section (The yellow arrow indicates a 50.0 mm

With type II angular pregnancy, which is often associated with angular villi or placental accrete, the risk of angular rupture is very high. It is recommended to terminate the pregnancy after confirming the diagnosis, as shown in Fig. 4. The pregnancy sac of a type III angular pregnancy (uterine horn and interstitial type) is located at the beginning of the uterine horn adjacent to the interstitial portion of the fallopian tube. Following the diagnosis of a type III angular pregnancy, surgery should be performed as soon as possible. The mode of operation can be seen in Fig. 4. If the gestational age of the type II or III angular pregnancy is greater than 12 weeks at the time of diagnosis, the risk of uterine horn rupture and massive bleeding is high. If the uterine horn has ruptured at the time of diagnosis, emergency laparotomy is recommended. If the patient with the type II or III angular pregnancy is clinically stable and there is no embryo in the gestational sac, with the informed consent of the patient, the direct hysteroscopic ultrasound-guided injection of methotrexate around the gestational sac can be carried out to reduce surgical injury and increase the probability of preserving fertility, referencing the minimally invasive conservative treatment of tubal interstitial pregnancy reported by Leggieri et al. [16].

Complications of angular pregnancy include uterine rupture, residual villi, or placental fragments in the angular region. In our study, four cases involved complications caused by incorrect clinical management due to ultrasound misdiagnosis in early pregnancy.

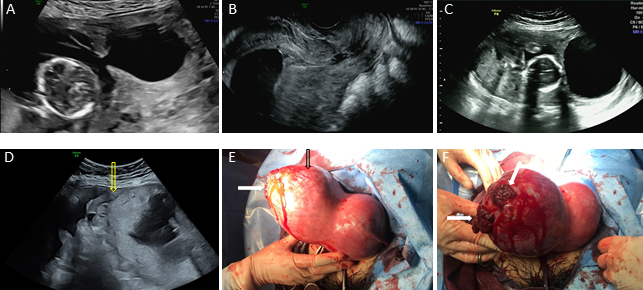

One case was previously diagnosed as normal early intrauterine pregnancy in a

separate hospital; however, the right angular protuberance without an angular

pregnancy was identified during an ultrasound examination at the 15th week of

pregnancy by a junior doctor at our institution. Five weeks later, the patient

experienced pain in the right lower abdomen, with a clear ultrasound diagnosis by

a senior doctor of a right angular and interstitial pregnancy with rupture of

angular location. The patient developed hemorrhagic shock and accepted emergency

laparotomy, with two lacerations (50.0 mm

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.The two-dimensional gray-scale ultrasound images and

intraoperative photos of a case of type III angular pregnancy. Ultrasound

examination at 15 weeks of gestation: (A) The fetus was found in the right

angular, and there was an adhesive band between the right angular and the uterine

cavity. (B) Only amniotic fluid without fetal structure was found in the middle

and lower part of the uterine cavity. Ultrasound examination at 20 weeks of

gestation: (C) The fetus was curled up in the right angular, and there was an

adhesive band between the right angular and the uterine cavity. (D) Rupture of

the right angular and hemoperitoneum (yellow arrow indicates the rupture of right

angular). Intraoperative photos: (E) The black arrow indicates that the right

angular is obviously protruding, and the white arrow indicates the rupture of the

right angular. (F) The white arrow indicates that two lacerations of 50.0 mm

For two cases that were diagnosed as normal intrauterine pregnancy, the patients requested termination. They underwent negative pressure uterine aspiration under ultrasound monitoring. Following the operation, residual pregnancy tissue was noted in the angular region and hysteroscopic tissue removal was performed under ultrasound guidance. Type I angular pregnancy was postoperatively diagnosed.

The fourth case was diagnosed as an endogenic angular pregnancy by ultrasound during the first trimester, without diagnosis of angular placenta accrete during the second and third trimester; the patient carried the pregnancy to a term vaginal delivery. The placenta did not deliver spontaneously and residual placental tissue and accrete in angular location was diagnosed by ultrasound.

The main strength of our study is that the sample size is large, providing a sufficient number of cases of angular pregnancy with different high-risk factors, pregnancy outcomes and customized management. As a result, we were able to ascertain the high-risk factors of angular pregnancy, the value of ultrasound diagnosis and individualized management scheme.

This study has two limitations. One limitation is that ultrasound doctors have different levels of experience, accounting for potentially wide range of diagnosis and management. The other limitation concerns the pathological diagnosis of placenta accrete. Manual abruption of placenta or retained placenta in situ limits the accuracy of microscopic diagnosis or the lack of micropathological diagnosis during pathological examination.

All providers caring for pregnant women should fully understand the ultrasonic diagnosis and classification criteria, clinical diagnosis criteria and pathologic diagnosis criteria for angular pregnancy. Different types of angular pregnancy entail different pregnancy outcomes and risks that require clinical management to be individualized for each patient. For the early identification of an angular pregnancy, ultrasound should be utilized to determine the type of angular pregnancy and to judge whether there is evidence for placenta accrete in the first trimester. Fine ultrasonic diagnosis is both feasible and crucial. This will allow the clinician to correctly determine risks to the pregnancy and to formulate a tailored management plan for the patient. This has the potential to reduce unnecessary medical termination of pregnancy and avoid adverse outcomes such as uterine rupture and massive hemorrhage. At the same time, ultrasonic diagnosis, and classification of placenta accrete during the second and third trimester in type I angular pregnancy is critical to the proper choice for time and mode of delivery.

LZ designed the research study. SHC gave guidance for the revision of the paper. LZ was responsible for ultrasonic diagnosis, collection, analysis of case data, writing and revision of the manuscript. SPD and YHY assisted in collecting ultrasound data. SHC and WL were responsible for obstetric patient management, operation, and data recording. RL, SMY and MFW were responsible for gynecologic patient management, operation, and data recording. Allauthors read and approved the final manuscript.

All patients involved in this study signed an informed consent and power of attorney before accepting an operation. This study is a retrospective and descriptive analysis of the data collected prospectively for routine clinical services. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of our institution (approval number: TJ-C20210403).

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped during the writing of this manuscript, to the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions, the editors for their comments and guidance, and to Ms. Wang Xinmiao for her advice in creating the schematic diagram.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.