Academic Editor: Peter A. McCullough

Supportive care may have significant input into the treatment of patients with heart failure (HF). Support, understanding and being treated as a whole and unique person are vital for patients with HF. In order to develop a person-centred program, it is important to know patients’ needs from their perspectives. The aim of the current review and meta-synthesis was to explore the needs of patients with HF from their perspective. A qualitative review was conducted using the keywords: (“needs” OR “need”) AND (“heart failure”) AND (“qualitative”) in four databases. Pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria were set. The ‘Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies’ item checklist was used to assess the research methodologies of the included studies. A “thematic synthesis” methodological approach was used: (1) Line by line coding of the findings from primary studies. (2) The resulting codes were organized into related areas thus building descriptive themes. (3) Analytical themes were developed. Eleven articles were included in the present review. The results from the meta-synthesis extracted five different categories covering patents’ needs: Self-management, palliative care, supportive care, social support and continuing person-centred care. The need for continuing empowerment and support to meet those needs was also identified, revealing the core theme: ‘Wind beneath my wings’. The meta-synthesis quotations highlighted the necessity for dynamic and interactive continuing person-centred care focusing on the ongoing patients’ needs through the HF trajectory. Giving more emphasis to the human dimension and holistic approach of patients with HF, along with cardiology medicine development might be a key factor in improving clinical outcomes and health related quality of life.

Heart failure (HF) is an important healthcare problem, and is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates [1]. Patients experiencing HF frequently have poor health related quality of life (HR-QoL), even when treated with modern evidence-based therapies [2, 3]; such as HF management programs, new pharmacotherapy approaches such as ACE-inhibitors and b-blockers, sacubitril/valsartran, and a comprehensive approach to patient care. HF often exists with other chronic diseases, especially in older patients, resulting in complex co-morbidity conditions [4]. HF affects 6–10% of the population aged 65 years old and over in the US, estimations have indicated with will increase to 25% of the population by 2030 [5, 6, 7]. It is also associated with high health care costs and reduced patient HR-QoL [2, 7, 8].

Progressive physical decline in advanced stages of the disease has been well documented, with distinct trajectories described for people with different progressive illnesses [9, 10]. As HF is a progressive syndrome, individuals usually experience physical and psychosocial issues, resulting in complex needs from the time of diagnosis until the end of their life [11]. Each exacerbation may result in death, and if the patient survives many such episodes, he/she will experience a gradual deterioration in health and functional status [12]. An individuals’ complex needs, comorbidities and symptom severity under an unpredictable trajectory creates palliative needs from the early stages [12]. Even though such issues should be addressed, palliative and end-of-life needs for patients with HF are often under-recognized and under-addressed [13, 14]. The notion of “total pain”, has been applied to the experience of having HF and therefore includes spiritual pain in which there is a lack of inner peace and personal integrity [15]. Psychosocial needs for patients with HF include empathy, counselling, independence on several factors including financial matters, support to fulfill family and social roles also the need to repair their sense of self where it has been disrupted by the syndrome [16].

People with HF not only experience losses in physical function but must also live with a variety of changes in their emotional, cognitive, social, economic and spiritual domains, which can result in a decline in their quality of life. Each patient has their own individual experience which can vary from patient to patient, it is usually unpredictable but invariably impairs his/her HR-QoL. At the same time, the literature shows that there are common aspects between these experiences [17]. Even though evidence exists for successful management programs that improve HF-related outcomes [18, 19], including readmission rates [20], testimonies from patients may show differing results (qualitative studies). Qualitative studies have already been carried out to explore the needs of patients with HF [4, 16, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. What is lacking in the literature, to date, is a summary of those needs which are related to topics in order to develop a comprehensive overview of patient needs, thus affording the opportunity to design a person-centred approach to care provision. A qualitative meta-synthesis provides the opportunity to intergrade and synthesize the literature published to date, thus guiding clinical practice and future research. In addition, the results of a meta-synthesis can help health professionals (HP) develop interventions focusing on the patient’s true needs and expectations whilst also enabling then to detect vital aspects of the patient experiences that are currently not being addressed.

In order to develop a person-centred program, it is important to know what patients’ needs are based on their own perspectives. This will contribute towards developing person-centred management programs. For people with HF, support, understanding, receiving comfort, and being treated as a whole and unique person are vital [23, 29]. These could be offered to a patient through supportive care as the “care that helps the patient and people important to them to cope with life-limiting illness and its treatment — from before diagnosis, through diagnosis and treatment, to cure or continuing illness, or death and bereavement” [30], which aims to improve their HR-QoL [31]. The aim of the current review and meta-synthesis was to identify the needs identified by patients with HF.

A literature review was conducted using a qualitative methodology. Zimmer et al., (2006) [32] stated that meta-synthesis involves the process of comparing, translating and analyzing the original results that leads to the generation of the new interpretations. Initially, a systematic review of the literature was conducted. Two researchers undertook the searches using the keywords: (“needs” OR “need”) AND (“heart failure”) AND (“qualitative”) in the PubMed, CINAHL, PsycoINFO, and EBSCO databases, with outputs published prior to, and including, December 2019. The researchers screened the titles of the articles retrieved and identified the potentially relevant publications. The eligibility of the relevant abstracts was examined separately by the two authors, who both reviewed all abstracts. The two authors used standard pretest selection forms, independently, to assess eligibility. A third author was involved to reach consensus when necessary.

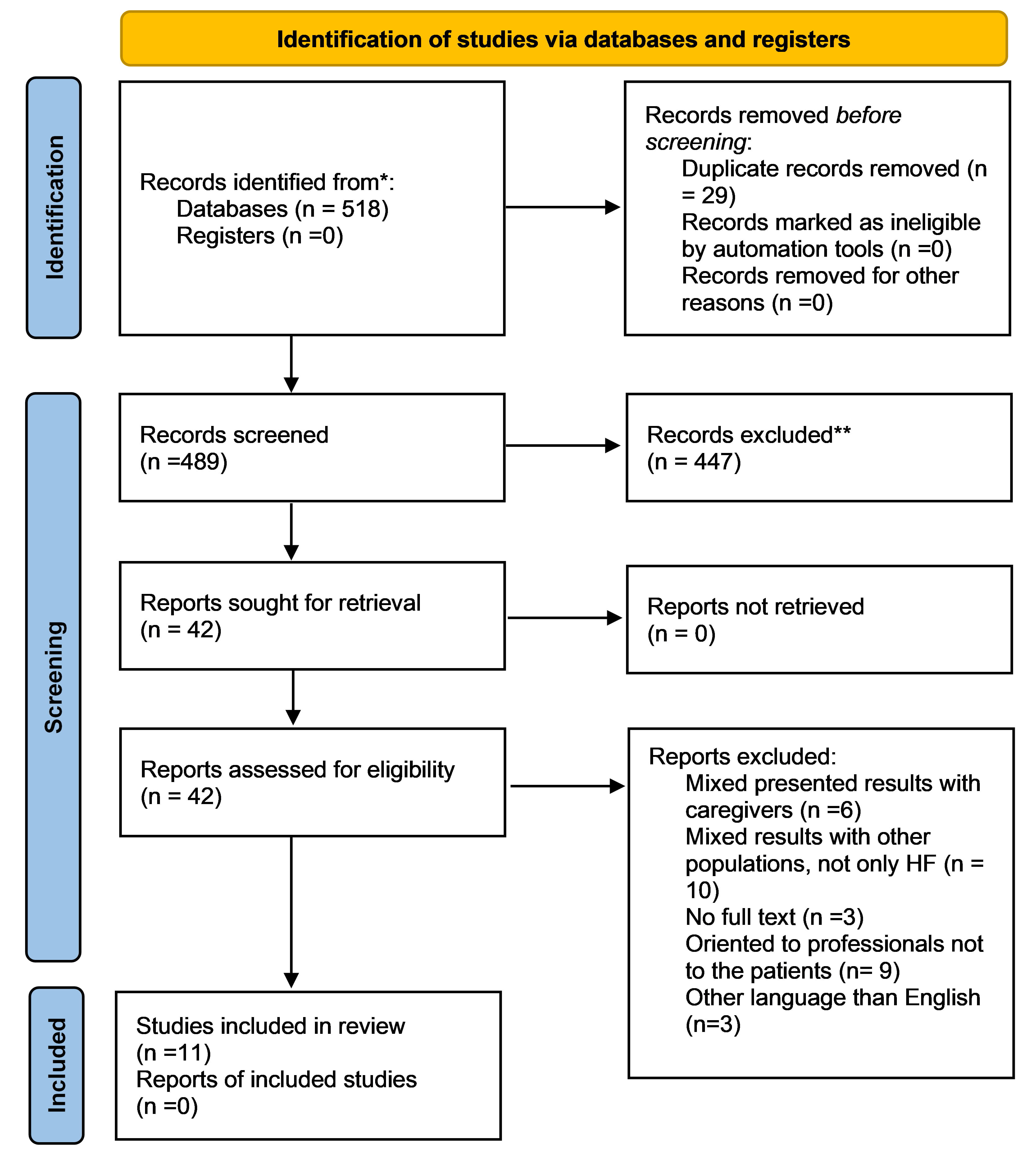

The inclusion criteria for the selection of the articles were standardized. Articles needed to use qualitative methodology involving patients with HF, and have explored patient needs from a patient perspective. Articles had to be published in the English language. Articles involving carers/caregivers were included in the review only where the patient results were presented separately. Exclusion criteria were defined as: articles including populations other than patients with HF or articles not presenting results for patients with HF separately, articles focusing on the patients’ experience or perspectives generally related to HF but not related to their needs, and studies exploring caregivers and/or family needs. The search yielded 518 articles from which 29 duplicates removed, a further 447 papers were excluded after the titles and abstracts of the articles had been reviewed. The remaining 42 articles were assessed for full eligibility, and 11 publications were found to fulfill the inclusion criteria and were therefore included in the systematic review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1). The main figures pertaining to the studies included are summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [4, 16, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 33]).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Flowchart of the included studies.*Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). **lf automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hofmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal. 2021; 372: n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.orq/.

| Author (Year) Country | Aim | Participants | Main findings |

| Cortis and | To explore the experiences of older | N = 10 | Four main themes: |

| William (2007) | adults with CHF and gain a deeper | 50% males | 1. Experiences of living with heart failure |

| UK [21] | understanding of their palliative and | Years of age (range) | a. Symptoms |

| supportive needs and the value of | 80–90 yrs old | b. Loss of independence | |

| possible interventions. | NYHA class: II–IV | c. Physical, psychological and social isolation | |

| d. Loss of self-esteem and self-worth | |||

| 2. Ways of coping | |||

| a. Stoicism and acceptance | |||

| b. Perception of heart failure | |||

| 3. Constraints to coping | |||

| a. Not being a burden | |||

| b. Expectations of care | |||

| 4. Developing resources for coping | |||

| a. Self-help and adaptation | |||

| b. Seeking reassurance | |||

| Harding et al. | To generate recommendations for | N = 20 | Five main themes: |

| (2008) UK [22] | information to CHF patients and | 80% males | 1. CHF symptoms and management |

| their family carers, in line with UK | 2. Disease progression and future care | ||

| and International policy guidelines. | 3. Living with inadequate information | ||

| 70% NYHA III | 4. Barriers to effective information provision | ||

| LVEF mean 34% |

5. Recommendations to improve information provision. | ||

| Bekelman et al., | To learn about patients’ and their | N = 33 | Six main themes: |

| (2011) [33] | family caregivers’ major concerns | (10F/23M) | 1. Major concerns and needs |

| and needs and to explore whether | 2. Physical aspects of care | ||

| and how palliative care would be | NYHA II–IV | 3. Psychological and psychiatric aspects of care | |

| useful to them. | EF mean = 31% | 4. Social aspects of care | |

| 5. Future of illness | |||

| 6. Structure and processes of care | |||

| Andersson et al. | To describe how people with HF ex- | N = 11 participants | Four main themes: |

| (2012) SE [23] | perience support in Swedish primary | (6F/5M) | 1. Being abandoned |

| healthcare. | 2. Lack of information | ||

| 3. An absent dialogue | |||

| 4. To develop strategies on one’s own | |||

| Gerlich et al. | To explore the needs and experi- | N = 12 participants | Three main themes: |

| (2012) DE [24] | ences of older patients with advanced | 50% males | 1. Understanding of illness and prognosis |

| HF in Germany. | a. Information needs | ||

| b. Source of information | |||

| c. Dealing with prognosis | |||

| 2. Health care services | |||

| a. Hospitals | |||

| b. In the community | |||

| c. Finances | |||

| 3. Social life | |||

| a. Social activities | |||

| b. Communication about illness with family, friends and neighbours. | |||

| Baudendistel et | To explore patient perspectives on | N = 17 participants | Five main themes: |

| al. (2015) DE | guided treatment of HF across mul- | (5F/12M) | 1. Quality of health care in general |

| [28] | tiple health care sectors. | 2. initial evaluation – establishment of diagnosis | |

| (EF |

3. Treatment and professional advice | ||

| 4. Follow-up | |||

| 5. Coordination of care | |||

| Klindtworth et | To understand how old and very old | N = 25 participants | Two main themes: |

| al. (2015) Ger- | patients perceive advanced heart fail- | A. Patient understanding of disease and prognosis | |

| many [4] | ure and to assess their medical, psy- | (14F/11M) | 1. Dealing with advanced heart failure and ageing |

| chosocial and information needs at | (NYHA III/IV) | a. Perception of heart failure | |

| the end of life. | b. Adaption to changing conditions | ||

| c. Appraisal of quality of life | |||

| d. Information regarding life | |||

| 2. Dealing with the end of life | |||

| a. Value and worthlessness in old age | |||

| b. Preparation for death | |||

| B. Delivery of health | |||

| 1. Perceptions regarding care | |||

| a. Appropriateness of medical care | |||

| b. Continuity of care | |||

| 2. Interpersonal relations | |||

| a. Interaction in the process of care | |||

| b. Specific aspects in physician-patient interaction | |||

| 3. Meaning of family | |||

| Ross et al. | To identify the spiritual needs and | N = 16 participants | Two main themes: |

| (2015) UK [27] | spiritual support preferences of end- | (7F/9M) | 1. Experience of healthcare and effects of the illness |

| stage heart failure patients/carers | a. Love and belonging | ||

| and to develop spiritual support | NYHA IV | b. Hope and coping | |

| guidelines locally. | c. Meaning and purpose | ||

| d. Faith, believe and existential issues | |||

| 2. Spiritual help/support | |||

| a. Home visiting service and telephone access | |||

| b. Care-coordinator | |||

| c. Voluntary Organisations | |||

| d. Supporting carers | |||

| Yu et al. (2016) | To explore the underlying percep- | N = 26 | Five main themes: |

| CN [26] | tions of information needs from the | (11F/15M) | 1. Living with inadequate information |

| HF patients themselves. | a. Poor understanding of HF | ||

| NYHA II–IV | b. Inadequate knowledge of medication | ||

| c. Uncertainty about coping strategies | |||

| 2. Content of information needs | |||

| a. Risk factors | |||

| b. Medication | |||

| c. Disease management strategies | |||

| 3. Motivators for information learning | |||

| a. Desire to improve their current health condition | |||

| b. Obligations towards other family members | |||

| c. Maintaining hope for the future | |||

| 4. Barriers to information acquisition | |||

| a. Economic concerns | |||

| b. Geographical inconvenience | |||

| c. Material-related and patient-related factors | |||

| d. Little communication with health professionals | |||

| 5. Preference for information deliver | |||

| a. Direct communication with health professionals | |||

| b. Written materials | |||

| c. The internet | |||

| d. TV programs | |||

| e. Newspaper | |||

| Kristiansen et | To identify the learning needs of pa- | N = 16 | Four main themes: |

| al. (2017) DK | tients with HF and ascertain what | (4F/12M) | 1. Learning needs experienced by patients between follow-up visits |

| [25] | they emphasize as being important in | Years of age (range) 47–78 | 2. Anxiety and uncertainty as driving forces for learning |

| the design of an educational website | yrs old | 3. Managing my condition | |

| for them. | 4. Managing my daily life | ||

| Namukwaya et | To describe patients’ experiences of | N = 21 | Five main themes: |

| al. (2017) UG | their illness, their perspectives of | 71.4% females | 5. Physical needs |

| [16] | their multidimensional needs and | Years of age (range) 18–70 | a. Need to control symptoms and for cure |

| what they and their HPs want to be | yrs old | 6. Information needs | |

| improved. | 7. Psychological needs | ||

| a. Need for reassurance | |||

| b. Need for empathy | |||

| c. Need for attaining life goals and live a normal life | |||

| d. Need for counseling and emotional support | |||

| 8. Spiritual needs | |||

| a. Need to maintain hope | |||

| b. Need to find the meaning of their illness and for spiritual support | |||

| c. Need to re-establish a sense of purpose | |||

| d. Need to feel cared for and to be treated with respect | |||

| 9. Social needs | |||

| a. Need for independence and for having control | |||

| b. Need for practical help and companionship | |||

| c. Need to fulfill family and social roles |

The methodological quality of the included articles was assessed using the ‘Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies’ (COREQ) item checklist (Supplementary Tables 1,2) [34]. This was conducted in order to gain an overview of the methodological quality of the studies included. No study was rejected due to low methodological quality. The checklist consists of 32 specific items for reporting qualitative studies and includes generic criteria that are applicable to all types of research reports. The criteria included support researchers to report upon important aspects of the research team, study methods, context of the study, findings, analysis and interpretations. The methodological assessment of the included studies is shown in Supplementary Tables 1,2.

In order to verify the validity of the interpretation within the texts, a “thematic synthesis” methodology was used to undertake the current meta-synthesis [35]. This method is a three-step process: (1) Free line by line coding of the findings of the primary studies. (2) Free codes extracted were then organized into related areas to build descriptive themes. (3) Analytical themes were developed [35, 36]. The first step, line by line coding of primary results, was conducted independently by five researchers. Researchers gave one code in each initial patient quote. The resulting descriptive themes, with a representative initial quote, are presented in Table 2 (Ref. [4, 16, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 34]). Additional information for all quotes from the primary studies, and their assigned codes, are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

| Codes | Description | Illustrative quotes |

| Individualized care | Patients asking for care based on each | “[…] Let them take time to know from the patient what they need” [16] |

| conditions, abilities, needs, routines, and goals | “ […] it is giving a certain kind of orientation to you […] things run fairly straight or if you to let things slide” [28] | |

| General information | Patients asking information for all aspects | “The most important thing is to also let the patient know what is going on […]” [16] |

| “[…] I know nothing about my disease […] and medications were just given to me” [23] | ||

| Information for medication | Patients asking information regarding | “I think if you don’t really know about them (medication) you’ll stop taking them” [21] |

| medication | “[…] you get too little information […] what effects they have.” [25] | |

| Information for HF disease | Patients asking information regarding HF | “I have no knowledge of HF […] I think it is more serious…I cannot describe it [HF] clearly…I really don’t know” [26] |

| “I did not know I had it […] I was almost shocked” [23] | ||

| Continuing education | Patients seeking resources of information | “I need a website where I can search for different symptoms and someone to talk to.” [25] |

| related to HF | “[…] it could be like a space for patients’ opinions or experiences” [25] | |

| Individualized education | Patients asking for education depending the need of each one, their preferences | “I’d like them to explain more in English to me exactly the reason why this isn’t working, that isn’t working… reasons for and why they are giving me that particular tablet” [22] |

| and special abilities | “[…] I have presbyopia […] I cannot understand [the written materials] if the materials […] the materials should be easy to understand” [26] | |

| “[…] I would like to know, what the problem is. I would like to know, what treatment I need which one I should emphasise” (Patient 8, Interview 1) [16] | ||

| Communication | Patients asking to communicate better with health professionals | “A simple conversation with the doctor. So, everything is explained to me, what it is all about and what is going on” [28] |

| “I think direct communication with health professionals is better […] health professionals are always very busy” [26] | ||

| Empowerment | Patients asking to support them provid- | “I needed somebody to build me back up” [27] |

| ing them with what they need to keep going | “[…] now I have to plan much more […] so I find it hard […] you need to go somewhere where you can rest” [25] | |

| “[…] People need some kind of counselling” [33] | ||

| Psychological support | Patients asking for support regarding psychological issues | “[…] And you start panicking and it starts mucking up your sleep […] play on your mind psychologically” [22] |

| Empathy | Patients asking someone to understand their emotions and imagine what | “The other thing is that they should also put themselves (the HPs) in the position of the patient especially when they are talking to them […]” [16] |

| someone else might be thinking or feeling | “[…] Some health care workers are rude, or tough, but this should be changed they HPs should also put themselves in the shoes of the patient especially when they are talking to them” [16] | |

| “[…] Most of the (providers) are just there for the medical part. They are not there to ask how you are really doing.” [33] | ||

| Spiritual needs | Patients seeking support regarding deep feelings and beliefs of a religious nature | “[…] So when I felt overburdened I said to myself if He says ‘I am the way the Truth and life and whoever knows this will be set free’ so I decided to be saved […]” [16] |

| “But I was, well, a bit frightened […] “Oh my God! What will still be there and remain when you are dead and gone?” […] everything is on order […] that reassures me now” [4] | ||

| Need for independence | Patients express the need to be independent regarding daily tasks | “Having to depend on others, that’s my greatest fear. I never want that to happen, but it will happen” [24] |

| “That is my family, they are young. I cannot even wash for them or cook for them when I want to, that is how it is with this disease […]” [16] | ||

| Management of therapy | Patients seeking ways to manage with all | “ […] I have to hold back. The heart somehow says: “Stop, don’t overdo it […]” [4] |

| actions related to the therapy | “[…] They stop me from walking or running properly, which is actually worse than the shortness of breath” [4] | |

| “[…] I think it’s more than being able to deal with one specific symptom. The hardest part is to understand you are going to deal with them all” [33] | ||

| Formal social support | Patients seek to be surrounded with people (family, friends, services) to support | “Well, for me my GP is a central person. […] if I had another illness, where I do need a specialist, the GP is still, at least for me, he is still the key person” [28] |

| them | “There is one health care worker […] So it is not good, they need to be trained” [16] | |

| Financial support | Patients seeking for financial resources/support | “[…] this illness started it is a problem so I stopped working […] I would like to eat but the financial situation does not allow me” [16] |

| “My biggest problem is poverty […]” [16] | ||

| Better health services | Patients asking for more organized and easy access to healthcare services | “[…] I live in a place which is not so developed […] we can only get the information from the newspaper or TV, the resources are too limited anyway.” [26] |

| “It is very difficult to get in contact with care professionals in primary and hospital care” [23] | ||

| Lifestyle modification | Patients seeking help for altering long-term habits. | “ […] Well, for me it was a challenge on acting more relaxed and doing less. In the past I did very much walking with my wife for hours … this is missing now completely […]” [28] |

| “[…] I am living not only for myself, but also for others […] I should give up my bad habit of smoking […] I need to learn more information, the more the better, to effectively control it.” [26] | ||

| Pain relief | Patients asking for analgesia and be free of pain | “I only want to feel better […] nothing good […] I don’t need anything, I can be quite alone. Pain everywhere” [4] |

| Symptom relief | Patients describe symptoms of heart failure and seeking for help to be relief | “[…] “You must absolutely do this” […] I have often wished that just close my eyes and the suffering would come to an end […] It’s as someone had put a rope around your neck and is choking you […] I was gasping for air and could not breathe” [4] |

| “make each day count […] live with as little suffering as possible” [26] | ||

| End of life | Patients seeking for support and care in | “This made me feel sick, uncomfortable. If you see what …Is this your last hour? […]” [28] |

| the end of life taking into consideration their preferences | “[…] let it be. My family knows exactly how I think and that’s the way it is” [4] |

In the next step, “new” codes were created to capture the meaning of the groups from the initial codes. This step of the methodology enabled the codes produced to be comparable. A draft summary of the findings organized by the descriptive themes produced was written by one of the researchers, then reviewed and revised by all of the researchers. Then, the researchers worked together to capture all of the linkages between the themes produced. A “map” was created, as shown in Fig. 2, with two themes and five sub-themes, to enable development of the final model. The researchers located similarities, then proceeded to group the codes into descriptive themes.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Second step of the meta-synthesis: free codes extracted with all possible linkages between the themes.

The final stage consisted of the researchers going beyond the systematic synthesis of primary studies, by interpreting the findings and results in a critical way. They started thinking the descriptive themes produced, first independently and thereafter as a group, which concluded in merging of the themes, which concluded with the production of five “new” themes. The “new” themes were created to combine similar needs which had emerged from the meta-synthesis. For instance, palliative care was the umbrella term for: pain relief, symptom relief and end of life care. This ‘new’ term/theme was created to cover all three themes. In this last step, the final themes were developed covering all topics related to the needs of patients with HF, as identified by the patients themselves. The final themes produced were: continuing person-centred care, social support, supportive care, palliative care and self-care management. In addition, all of the discussions between the researchers revealed the need for continuing support of the patients in order to be able to cope with the needs arising throughout the HF trajectory; and that is how the core theme ‘Wind beneath my wings’ arose (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Final themes covering all topics related to patients with heart failure needs.

From the systematic review eleven studies were assessed as eligible and were included in the present review and meta-synthesis. Through the three-step process of the thematic synthesis one core theme (namely ‘Wind beneath my wings’), and five main themes were revealed: continuing person-centred care, social support, supportive care, palliative care and self-care management. A description and relevance of the core theme, and each of the main themes, is listed below.

Researchers identified the mechanisms to meet patient needs, extracted from the literature review and meta-synthesis, that covers continuing empowerment and support illustrated by the core theme: ‘Wind beneath my wings’. The results also showed five different categories to cover patents’ needs, which interacted with each other: Self-management, palliative care, supportive care, social support and continuing person-centred care (CPCC).

“[…] I would like to know, what the problem is. I would like to know, what treatment I need which one I should emphasize” [16].

All themes are correlated between each other as shown in Fig. 3, starting from the self-care management and ending up with a continuing process, with the patient in the centre.

Self-care is the cornerstone of HF management. Self-care comprises of adherence to behaviors, such as maintaining a low sodium diet and medication regimen, as well as symptom monitoring (self-care maintenance) to maintain physiological stability and response to symptoms when they occur (self-care management) [37].

“[…] How to protect myself and avoid risk factors […] As long as I have ways to obtain the information, I hope I can get as much information as I can” [22].

Palliative care for patients with HF has a dual role by both treating symptoms and ensuring that patients’ treatment plans match their values and goals [38, 39]. According to WHO [30] palliative care provides care in the relief of pain and other distressing symptoms; affirms life, and regards dying as a normal process; intends neither to hasten nor postpone death and offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until they die. This holistic approach also addresses the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care and supports families and informal careers during the illness and into bereavement.

“This made me feel sick, uncomfortable. If you see what …Is this your last hour? […]” [24].

Supportive care is necessary throughout the HF trajectory in order to manage physical and psychosocial issues, and comorbidities, to preserve or improve QoL for patients and their families [38]. Supportive care should be responsive in changing patient’s needs, especially during times of increased vulnerability, such as after hospital discharge. Supportive care in HF comprises of four different components; communication, education, symptom management, and psychological and spiritual issues [40]. Thus, the four above components created the “new” theme entitled ‘supportive care’.

“[…] it’s good when you have someone who looks after you […] I do not want too much care […] too much responsibility” [4].

Supportive care is “the care that helps the person and people important to them to cope with life-limiting illness and its treatment—from before diagnosis, through diagnosis and treatment, to cure or continuing illness, or death and bereavement” [40].

Social support is a multi-faced concept that positively influences disease-related outcomes in multiple chronic illnesses, including HF [41, 42].

“I don’t meet people […] very very lonely. Very very lonely” [23].

“I am worried I do not have someone to live with. I live here alone no one even to make me a cup of tea” [16].

Four types of social support have been found to influence disease-related outcomes in patients with HF, including emotional support, instrumental/tangible support, informational support, and appraisal support [42]. Social support distinguishes between informal and formal. The former refers to family members, friends, neighbors, and others, while the latter refers to professionals/public services [43].

CPCC is advocated nowadays as a key component of effective illness management [44, 45]. Giving the patient the opportunity to introduce her/himself as a person in the form of an illness narrative is the starting point in creating a collaborative, egalitarian provider-patient partnership that encourages and empowers patients to actively take part in finding solutions to their problems [44].

“No, no, nothing about that at all. Just this great stream of medicines, between puffs and pills.” [18].

“I suppose they do (explain symptoms) but it hasn’t penetrated.” [18].

“What they explain (to) me, I forget.” [18].

“[…] But who is going to explain it to me so that I understand? I haven’t met anyone yet who can do that.” [20].

This meta-synthesis provides an illustration of some of the needs that occur in the lives of patients with HF. The main themes, discovered from the results, covered patients’ needs depended upon fluctuations occurring in the illness trajectory, patients’ functional status and illness severity [38]. Although these revealed themes have already been reported in previous studies as important aspects in HF management, the new input highlighted here is that they come directly from patients with HF themselves, and the challenge is now to find mechanisms to respond to them in an ongoing process.

The current meta-synthesis provides information focusing in two aspects of HF management. Firstly, the important active role of the patient being the protagonist in dealing with his/her illness, and secondly the results highlighted that the actions of all the mechanisms of disease control needed to reach the patient with HF and his/her needs.

Either way, the results remain the same, health care professionals (HPs) should consider all of these aspects, and in collaboration with the patient find ways of addressing their specific needs. Each person is unique and has a different perception of his/her life, even when experiencing similar situations of uncertainty and restriction with others [45]. Thus, the key solution remains person-centred care. Ekman et al. (2011) [44] refers to giving the person the opportunity to present her/himself as a person in the form of an illness narrative as a starting point for building a collaborative, egalitarian provider (care and treatment expert)-patient (person expert) partnership that encourages and empowers persons to actively take part in finding solutions to their problems. “Wind beneath my wings” is the role of the HPs (the wind), who encourage patients (the wings) to take part in their care, to control and take decisions for their own health and HR-QoL. Patient empowerment helps increase patient awareness as well as encouraging mutual trust and open communication between patients and HPs [46]. Following HF patients in a closer manner, checking limitations and ensuring that changes which frequently occur are identified, especially in an unpredictable syndrome as HF, is valuable [17]. One of nurses’ priorities is to get to know the patient and how this patient copes with the syndrome [45, 47].

It is important that HPs place the patient with HF at the centre of every care effort and help him/her to address his/her unmet needs, thus achieving the best possible HR-QoL [44]. Kane et al. (2015) [17] refer to CPCC as the answer to the management challenges for HF, by incorporating patient preferences, values, beliefs, illness understanding, illness experience and information needs. All of the above are considered within the decision-making processes, encouraging patient engagement and collaborative goal setting. But is this enough to address the unmet needs of HF patients?

The answer is CPCC in the context of supportive care. Supportive care could be developed and provided starting from a CPCC perspective. The concept of CPCC integrates patient and family preferences and needs into the goals of care, manages symptoms to the level of comfort desired, and attempts to reduce the burden of illness on both the patients and their families [48]. In order to undertake this, HPs should extrapolate the unmet needs of each patient with HF via ongoing processes, as the needs change rapidly depending on the trajectory of the illness [9]. Therefore before providing supportive care, it is necessary for HPs to assess patient’s needs and develop a concrete and consistent process that regularly monitors patients’ with HF needs [44]. Supportive care is multidisciplinary holistic care provided for the patient and their family alongside the medical treatment(s), from the time of diagnosis aiming to prolong life and improve HR-QoL, and continues through into end of life care [49].

Even though a lot of successful management programs and therapies have been developed for HF patients, evidence show that people with HF frequently lack HR-QoL [20], and do not always feel that HPs respond to their needs [44]. Continuous supportive care throughout the illness trajectory may change the perception of the care provided.

The meta-synthesis quotations constitute the need for a CPCC model in patients with HF, that focuses on the ongoing needs of the individual and adapt as the needs change according to the passage of time, the evolution of his/her syndrome, their socio-economic factors [50], their environment, abilities, family and friends environment [51], the country’s health care system, the technology and the possibilities of its application in everyday life and in chronic diseases [52], in short it is the general supportive care of a patient with HF across its entire spectrum and range of expressions [33].

More investigation and research is necessary to document the appropriateness of this care model, and the possible implications for all parties in HF care such as patients with HF, their families, medical doctors and other HPs, the community and state parties.

Our meta-synthesis has certain limitations. Following completion of the literature review, the studies which were included were qualitative studies with limited numbers of participants, cumulatively from all 11 studies, 190 patients with HF were involved. It is understandable that the number of patients cannot be considered as representative of all patients with HF. However, this meta-synthesis examined prospects, views and thoughts of patients with HF, and is the first study to do this within this specific population.

The strength of this meta-synthesis is that the meta-synthesis team comprised of qualified cardiology and HF advanced nurses and a practicing physiotherapist, all dedicated to caring for patients with HF throughout the entire disease trajectory.

This review gives valuable information for what patients really need. The results may contribute to further develop management programs for HF patients, which become more effective in terms of clinical outcomes including adherence to therapies, acute events, HR-QoL, perceived care, and re-hospitalization.

The use of supportive care in a CPCC management program, may tackle obstacles in patient non-adherence and bad communication with HPs.

MK and EL designed the research study. All authors contributed towards analyzing the data (EL, MK, KP, AS, IL), and AS, KP and IL wrote the methodological assessment and the results of the manuscript. MK and EL wrote the rest of the manuscript. All authors read, made changes and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.