1 Graduate School of Xinjiang Medical University, 830000 Urumqi, Xinjiang, China

2 Clinical Laboratory Diagnostic Center, General Hospital of Xinjiang Military Command, 830000 Urumqi, Xinjiang, China

3 Department of Neurosurgery, General Hospital of Xinjiang Military Command, 830000 Urumqi, Xinjiang, China

Abstract

Hypoxic hypoxia arises from an inadequate oxygen supply to the blood, resulting in reduced arterial oxygen partial pressure and a consequent decline in oxygen diffusion into tissue cells for utilization. This condition is characterized by diminished oxygen content in the blood, while the supply of other nutrients within the blood remains normal. The brain is particularly sensitive to oxygen deficiency, with varying degrees of hypoxic hypoxia resulting in different levels of neural functional disorder. Since the brain has a specific threshold range for the perception of hypoxic hypoxia, mild hypoxic hypoxia can trigger compensatory protective responses in the brain without affecting neural function. These hypoxic compensatory responses enable the maintenance of an adequate oxygen supply and energy substrates for neurons, thereby ensuring normal physiological functions. To further understand the hypoxic compensatory mechanisms of the central nervous system (CNS), this article explores the structural features of the brain’s neurovascular unit model, hypoxic signal transduction, and compensatory mechanisms.

Keywords

- hypoxic hypoxia

- hypoxic signal transduction

- hypoxia compensation

- CNS

- neurovascular unit

Hypoxic hypoxia occurs when inadequate oxygen enters the blood, resulting in a decrease in the partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood and a decrease in the amount of oxygen diffused by blood to be utilized by tissue cells [1]. This condition can be caused by a low partial pressure of oxygen in inhaled air, such as being on a plateau or in upper-air conditions [2], and by external respiratory dysfunction, such as respiratory stenosis, obstruction, and lung diseases [3]. Hypoxic hypoxia is characterized by low blood oxygen levels, but the supply of other nutrients in the blood is normal. The brain is most sensitive to hypoxia, and the mechanism of hypoxia damage to the central nervous system (CNS) is complex, mainly related to cerebral edema and neuronal damage [4]. The brain’s response to varying degrees of hypoxic hypoxia includes different levels of neurological dysfunction. Acute severe hypoxia can lead to headaches, irritability, convulsions, coma, and even death, while chronic moderate hypoxia may result in symptoms like fatigue, lethargy, inattention, and memory loss [2, 5]. Given that the brain possesses a specific threshold for perceiving hypoxic hypoxia, instances of mild hypoxic hypoxia falling outside this range may induce a compensatory protective response in the brain, without impacting neurological function. Typically, mild hypoxic hypoxia triggers the brain’s compensatory mechanisms to maximize the provision of sufficient oxygen and energy substrates to neurons, thereby safeguarding the normal physiological functions of neuronal cells [6, 7, 8, 9]. This paper delves into the hypoxic compensatory mechanisms of the CNS by reviewing the structural attributes, hypoxia signaling pathways, and compensatory mechanisms within the neurovascular unit (NVU) model of the brain.

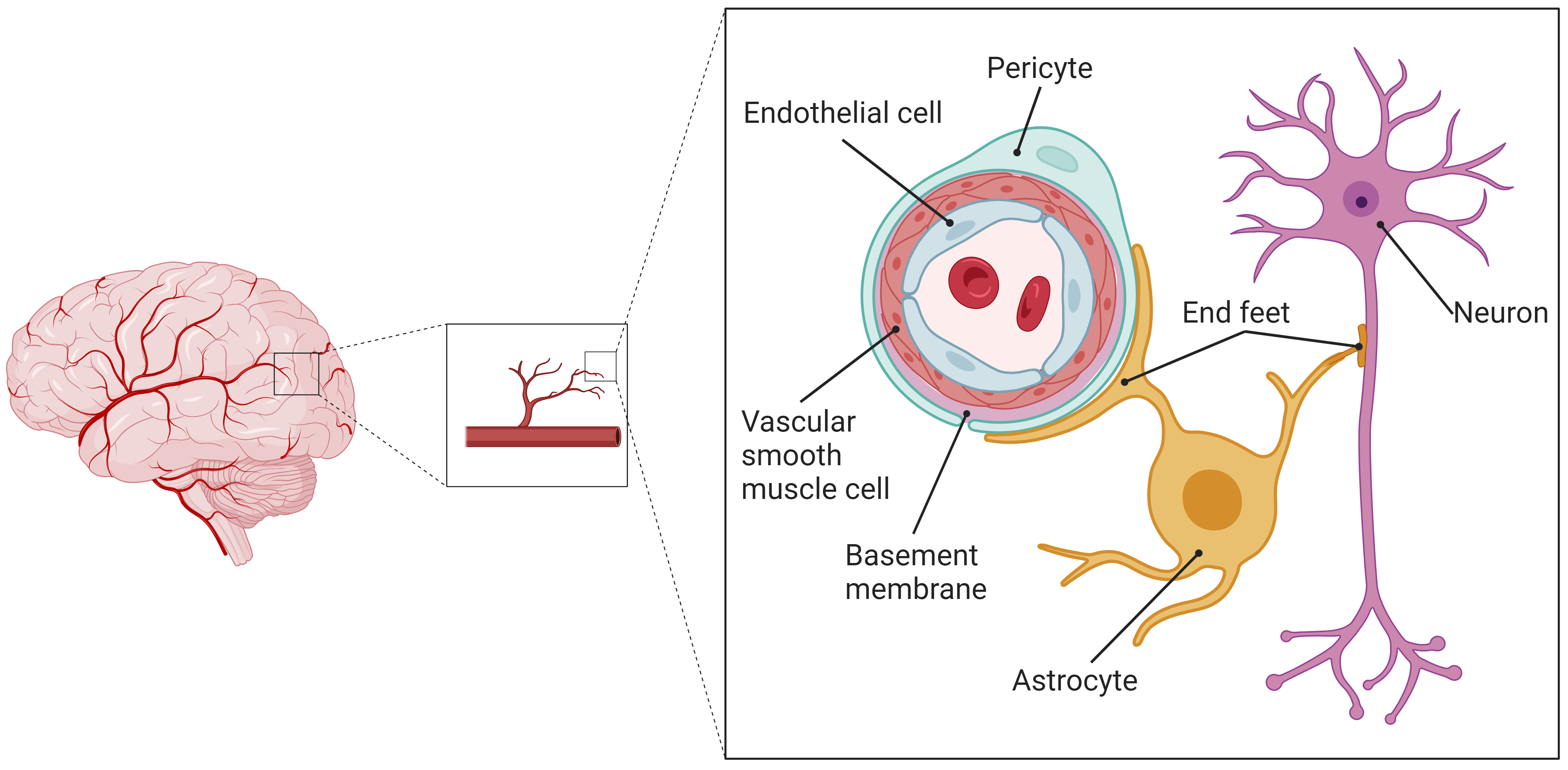

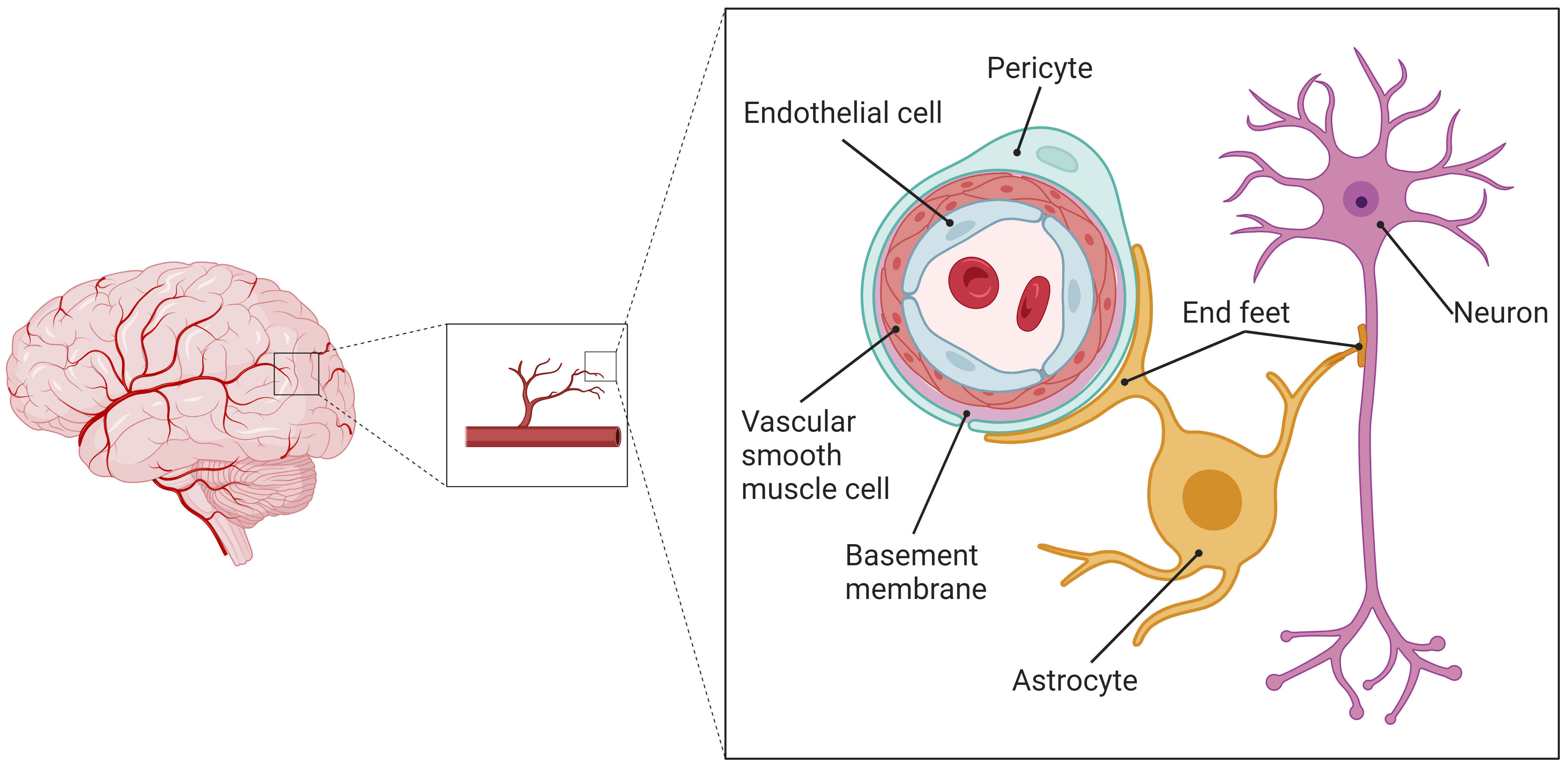

The structure and function of the nervous system are both complex and sophisticated. The biological roles of blood vessels, glial cells, and neuronal cells are interlinked; therefore, they should not be examined separately. Instead, analyses should cover the entire structural and functional network of the nervous system, with a focus on the interactions and signal transduction processes among various cell types within the CNS microenvironment. As a result, some scholars have introduced the concept of the NVU model [10], which suggests that the CNS functions as a unified system consisting of numerous NVUs. An NVU is defined as the smallest structural and functional unit within the CNS. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is composed of vascular endothelial cells (VECs), vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), basement membranes, astrocyte end-feet, and pericytes. This BBB, together with neurons, constitutes a comprehensive NVU model, wherein the VEC, VSMC, pericyte, astrocyte, and neuron comprise the core components of an NVU, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the structure of the cerebral NVU. The cerebral CNS constitutes an integrated system of numerous NVUs, which serve as the cerebral CNS’s smallest structural and functional units. These units comprise VECs, VSMCs, basement membranes, pericytes, astrocytes and their end-feet, and neurons. NVU, neurovascular unit; CNS, central nervous system; VECs, vascular endothelial cells; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells. The figure was made by BioRender https://www.biorender.com/.

Astrocytes cover over 90% of the microvessel walls within the NVU, participating in material exchange and information transfer with the VECs [10, 11]. Functioning as a foundational support of the neuronal network, astrocytes’ end-feet enclose and occupy the interspaces at neuronal cell synapses. They act as a crucial conduit and intermediary between microvessels and neurons, enabling interactions and information exchange among NVU’s constituent cells [12].

The NVU is critical in supporting cerebral health, with its functions being diverse. Initially, astrocyte end-feet envelop microvessels to strengthen the BBB structural base and to modulate its permeability. These astrocytes also regulate capillary blood flow by producing vasoactive agents, such as nitric oxide (NO) and products of cyclooxygenase (COX) activity. This regulation is vital for neovascularization and for encouraging the formation of tight junctions among VECs, which is crucial for maintaining the BBB’s structural and functional integrity [11, 12]. Furthermore, astrocytes provide neurons with both structural support and a metabolic microenvironment that facilitates material exchange. Demonstrating excitability, astrocytes respond to neuronal activity by influencing neuronal morphology, guiding axon growth, and encouraging synapse formation. They also affect the placement and array of ion channels, participate in synaptic signaling, and contribute to synaptic plasticity through the release of neurotransmitters. Moreover, astrocytes are key in supporting neuronal development and regeneration, aiding these processes by secreting various cytokines [13].

Another vital aspect of NVU functionality is neurovascular coupling (NVC) [14]. Neuronal activity elicits electrical impulses and triggers the release of neurotransmitters, which serve as catalysts for NVC [15]. Astrocytes, specifically, respond to these neural signals by emitting a range of signaling molecules, including calcium (Ca2+) waves. These waves, in response, influence vascular reactions, resulting in either vasodilation or constriction. Such changes in blood vessel diameter are crucial for modulating cerebral blood flow (CBF), guaranteeing that the metabolic needs of active neural tissues are adequately satisfied [16].

The NVU model effectively partitions the cerebral CNS into countless, distinct structural and functional units. This partitioning greatly simplifies the complexity associated with studying the nervous system’s functionality. As a result, in vitro cell co-culture experiments utilizing the NVU model facilitate focused studies on material metabolism and signaling between cells, providing a crucial experimental method for investigating interactions and signaling within the CNS’s microenvironment and among its diverse cells.

The hypoxic compensatory response is an organism’s mechanism to mitigate damage from systemic or localized hypoxia to cells, organs, or the organism itself [17]. Hypoxia exerts significant stress on organisms, with the brain being a sensitive target organ for hypoxic stress injury. In reaction to the degree and duration of hypoxia in CBF, the NVU, a pivotal unit in the CNS, initiates a hypoxic compensatory response, ensuring continuous supply of energy substrates to neuronal cells to maintain normal brain function.

Following hypoxia, cells detect the reduction in oxygen supply, primarily through hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), the central molecule triggering the cellular hypoxic compensatory response. During brief periods of mild hypoxia, intracellular HIF-1 accumulation stabilizes the cellular environment, adapting to hypoxic conditions and acting as a powerful endogenous defense against hypoxic injury. In contrast, prolonged severe hypoxia causes HIF-1 to induce neuronal cell apoptosis, leading to neurotoxic effects [18].

HIF-1 is a heterodimer consisting of

Oxygen, acting as a cofactor in PHD’s catalytic process, is the primary regulator of HIF-1 activation. It is transported through the bloodstream and diffuses to tissues and cells near these vessels. The distribution of blood vessels differs across organs or tissues, resulting in varied physiological partial pressures of oxygen in different locations [4, 26]. For instance, capillary endothelial cells experience a physiological oxygen partial pressure of 30–100 mmHg within the blood vessel, while in organs or tissues, it ranges from 8–72 mmHg [27]. Thus, the perception of hypoxia differs among cell types. Through specialized techniques, the physiological partial pressure of oxygen in brain tissues, home to astrocytes and neurons, was determined to be between 23.8 and 33.3 mmHg [28]. This reflects a disparity in the hypoxia perception threshold between VECs at the blood’s proximal end and astrocytes or neurons in brain tissue. Hypoxia signaling may occur when VECs detect blood hypoxia, while astrocytes do not detect internal environmental hypoxia. Additionally, given the varying distances of NVU model’s constituent cells from the microvasculature, VECs are the first to detect a reduction in blood oxygen partial pressure, followed by astrocytes and neurons during mild or early hypoxia. In cases where only VECs detect hypoxia, they can relay hypoxic signals to downstream astrocytes and neurons. Furthermore, VECs can augment local oxygen supply by launching a hypoxic compensatory response. Even after detecting hypoxia, they continue to compensate by increasing oxygen supply to astrocytes and neurons within the brain tissue. It is crucial to communicate hypoxic signals to astrocytes or neurons promptly, enabling them to begin their hypoxic compensatory responses as quickly as possible.

Beyond oxygen, cofactors of PHD also include Fe2+, 2-OG,

and ascorbate, addition to cellular molecules like neonatal NO and superoxide,

which are associated with PHD activation [21]. Given the complex interplay of

cellular interactions and the substance metabolism microenvironment in the NVU,

these cofactors or molecules may be influenced by other factors within the

cellular microenvironment, affecting hypoxia signaling or the regulation of

hypoxic compensatory responses. Crucially, NO is a vital cellular messenger

molecule engaged in various physiological and pathological processes, playing a

pivotal role in the cardiovascular, CNS, and immune systems of the organism [29].

During hypoxia, NO, produced and released by endothelial nitric oxide synthase

(eNOS) in VECs, diffuses into VSMCs, activating soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC)

and producing a vasodilatory effect to enhance local oxygen supply [30, 31]. This

process is part of hypoxia signaling. In addition to its vasodilatory effects, NO

also affects the stability of HIF-1

NO, as a signaling molecule, possesses the unique ability to enable

communication between two or more cells, achieved through its property of free

diffusion. It has been shown that NO at physiological concentrations can prevent

the breakdown of HIF-1

The hypothesis is that a NO-mediated signaling pathway for hypoxia operates

between cerebral VECs and astrocytes. Within this pathway, NO from cerebral VECs

diffuses towards astrocytes, triggering their hypoxic response by preventing the

degradation of HIF-1

It is crucial to acknowledge the challenges involved in determining a “physiological concentration” of NO, given its transient nature, varied mechanisms of action, and the complexity of its interactions with various cellular targets. Research shows that NO concentrations in vivo can vary widely, ranging from nanomolar (nM) to micromolar (µM) levels [43, 44]. These fluctuations depend on the type of tissue, the state of health or disease, and the method used for measurement. As a result, the exact physiological concentrations of NO are not fixed but rather are the subject of continuous investigation.

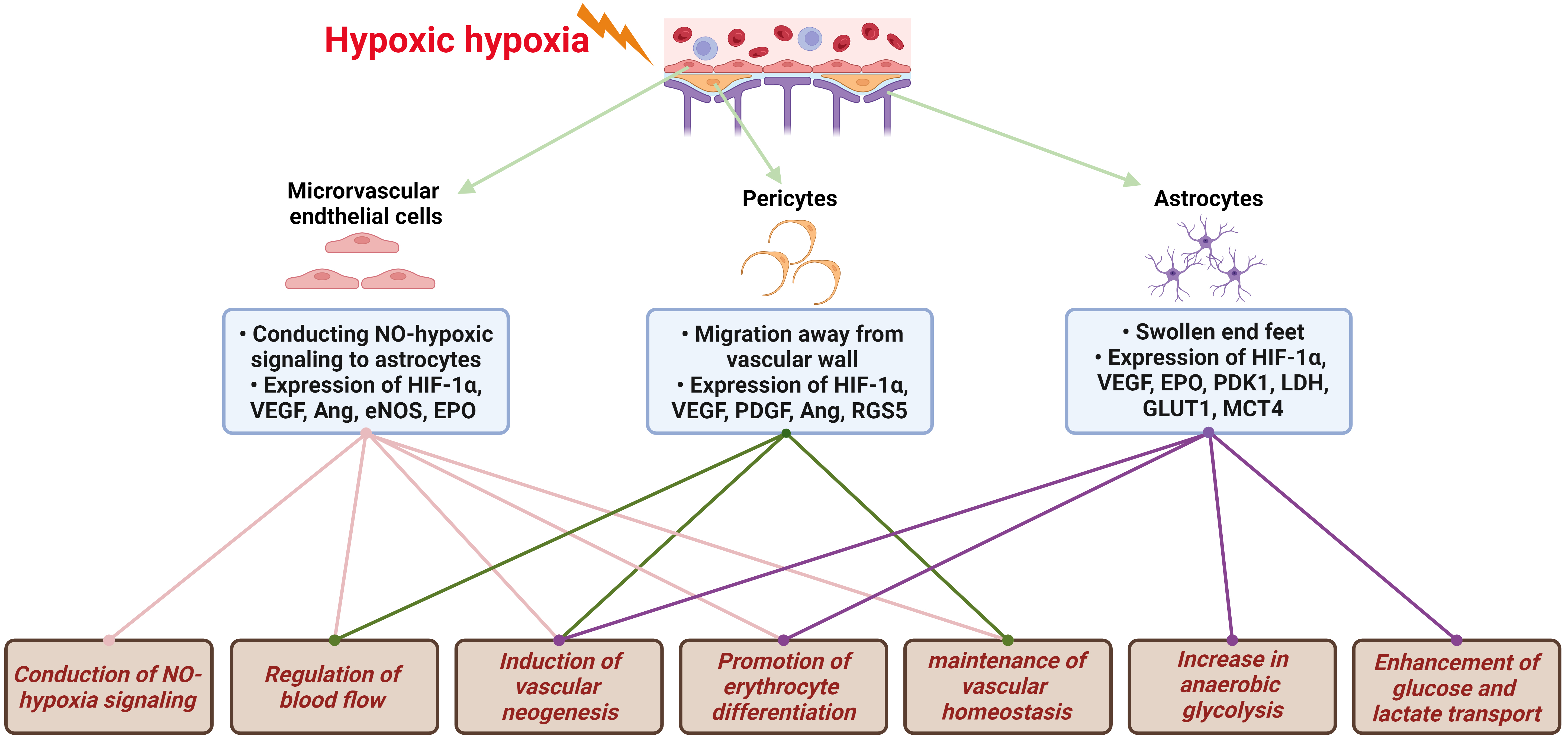

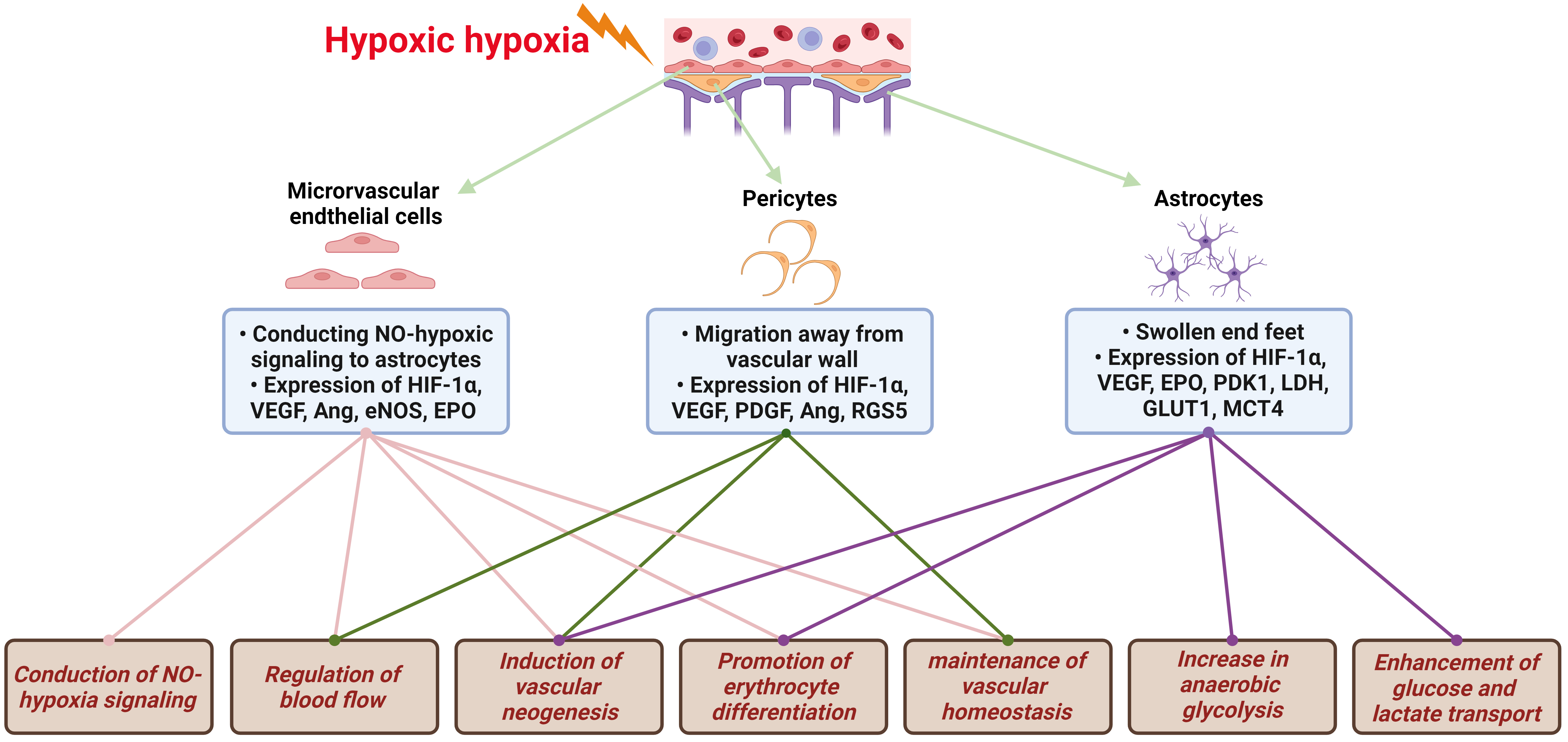

The brain, notably sensitive to hypoxia, depends on VECs, the fundamental structural component of the BBB, to initially recognize decreases in blood oxygen partial pressure. This recognition initiates a series of hypoxic compensatory responses within the vascular system. These responses encompass the conduction of NO-hypoxia signals, vasodilatation for blood flow regulation, vascular neogenesis, erythrocyte differentiation promotion, and vascular homeostasis maintenance, all designed to enhance local oxygen supply, as illustrated in Fig. 2. In response to hypoxia, VECs are the first to note the reduction in oxygen partial pressure, prompting a variety of vascular system compensatory actions. The foremost and most critical of these actions is the emission of NO, which then diffuses to VSMC, causing vasodilation. The vasodilatory effect of NO stems from its activation of sGC in VSMCs by binding to heme Fe2+, resulting in vascular smooth muscle relaxation and an increased oxygen supply [30, 31].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Hypoxic signal transduction and compensatory protective

mechanisms in NVU. The brain, exceedingly sensitive to hypoxia, reacts to

decreases in blood oxygen partial pressure through the NVU. This triggers a

series of hypoxic compensatory responses, including NO-hypoxia signaling

conduction, regulation of blood flow, induction of vascular neogenesis, promotion

of erythrocyte differentiation, maintenance of vascular homeostasis, increase in

anaerobic glycolysis, and enhanced glucose and lactate transport. NVU,

neurovascular unit; NO, nitric oxide; HIF-1

The vascular system’s compensatory acclimatized response to hypoxia includes modulating angiogenesis, establishing neo-capillary circulation, and increasing capillary plexus density to bolster local oxygen supply. This process incorporates various factors that contribute to vascular neogenesis following hypoxia in the NVU, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), platelet-derived factor (PDGF), angiopoietin (Ang), erythropoietin (EPO), etc. [18]. VEGF, a downstream gene of HIF-1, is expressed in VEC, astrocytes, and neurons following cerebral hypoxia injury [45]. It binds to receptors [vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR-1), VEGFR-2] on VEC. The VEGF/VEGFR-1 pathway initiates the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) signaling pathway in VEC, exhibiting anti-apoptotic effects [46], while the VEGF/VEGFR-2 pathway activates Akt and p38 signaling pathways, encouraging vascular neogenesis [6]. FGF, encompassing acidic and basic variants (aFGF, bFGF), demonstrates up-regulated mRNA transcript and protein expression levels in areas affected by brain hypoxia injury [47, 48]. Animal studies have shown that aFGF and bFGF can promote vascular neogenesis by enhancing vascular endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and lumen formation [49, 50]. PDGF encourages the division and proliferation of VEC. Its expression and that of its receptor are elevated in cerebral VEC and pericytes in middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model mice, facilitating vascular neogenesis and capillary reconstruction [51]. Ang, comprising Ang-1 and Ang-2, engages the common receptor Tie-2 on VEC. Ang-1 binding to Tie-2 induces mesenchymal cell differentiation, stimulates basement membrane deposition, and promotes intercellular adhesion, aiding in vascular neogenesis and stability. Conversely, Ang-2, a competitive antagonist of Ang-1, deters vascular neogenesis [18, 52, 53]. EPO, also a downstream gene of HIF-1, is secreted by the kidneys following hypoxic stimulation. It enhances nuclear erythrocyte division, increasing erythrocyte numbers in the blood and improving local oxygen supply by raising blood oxygen capacity [7, 54], representing another strategy of compensatory acclimatized response to hypoxia.

Pericytes, cells that envelop microvessels or capillaries, are widely

distributed throughout the microvascular network and play a critical role in the

NVU model, acting as one of the initial responders to cerebral hypoxia signals

[55, 56]. They perform various neurovascular functions through receiving,

coordinating, and processing signals from adjacent cells [57]. This includes

HIF-1

Astrocytes serve as intermediaries between microvessels and neurons, playing essential roles in cellular protection against hypoxia. This entails enhancing anaerobic glycolysis, facilitating glucose and lactate transport, and secreting VEGF and EPO to support angiogenesis and erythrocyte differentiation, as shown in Fig. 2. They minimize their own oxygen consumption by increasing their anaerobic glycolysis capabilities, thereby boosting glucose uptake and lactate export to provide neurons with enhanced oxygen and energy substrates. Astrocyte-dependent HIF-1 transcriptional regulation targets key enzymes in anaerobic glycolysis, including pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). The mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) is responsible for the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate (Pyr) to reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and acetyl coenzyme A (Acetyl CoA), entering the TCA cycle to produce ATP [65]. During hypoxia, HIF-1 activation leads to PDC inhibition by upregulating PDK1, decreasing oxygen consumption by the TCA cycle and redirecting Pyr to the anaerobic glycolytic pathway [8]. LDH facilitates the conversion of Pyr to lactic acid (LAC) and vice versa. It consists of a tetramer of subunits, mainly LDH-M and LDH-H, encoded by the LDHA and LDHB genes, respectively [66]. Hypoxic activation of HIF-1 induces LDHA overexpression, enabling Pyr conversion into LAC in the anaerobic glycolytic pathway [67]. LDH produces significant LAC amounts, which accumulate intracellularly and are then transported to neurons as an energy substrate. Interestingly, excitatory neurons prefer extracellular LAC over glucose as their primary energy source under both hypoxic and aerobic conditions [9]. In addition to regulating key enzymes of anaerobic glycolysis, HIF-1 also influences crucial enzymes in glucose metabolism, such as hexokinase (HK1, HK2), phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK1), enolase (ENO1). The upregulation of these enzymes enhances glucose metabolic conversion. Together with enzymes supporting anaerobic glycolysis, this increases LAC production, thus ensuring an adequate energy substrate supply for neuronal metabolism [68].

Glucose is the primary energy source for neuronal cells, but it cannot freely traverse the cell membrane’s lipid bilayer. Instead, it relies on glucose transporter protein (GLUT) embedded in the cell membrane for its passage from outside to inside the cell. Hypoxia-activated HIF-1 induces the upregulation of the GLUT1 gene transcription and expression, thereby enhancing cellular glucose uptake to satisfy the high glucose demands of anaerobic glycolysis [69, 70]. The anaerobic glycolysis pathway in glucose metabolism transforms Pyr into a significant quantity of LAC, leading to its accumulation intracellularly [67]. Consequently, LAC must be rapidly transported out of the cell and provided to neurons as an energy substrate. This process is facilitated by monocarboxylic acid transporter (MCT) proteins. Hypoxia-activated HIF-1 initiates the upregulation of MCT4 gene transcription and expression in astrocytes, facilitating LAC efflux to neurons under hypoxic conditions [71, 72]. Additionally, HIF-1 promotes the expression and secretion of VEGF and Ang-1 in astrocytes, supporting neovascularization and reconstruction [73, 74]. It also enhances the expression and secretion of EPO, which improves erythrocyte differentiation and increases blood oxygen capacity [75, 76].

There is an emerging agreement that brain cells are interdependent, and the neurologic microenvironment, coupled with various cellular interactions and signaling, constitutes the structural and functional network of the brain. Research on brain hypoxia and hypoxic compensatory responses should focus on the overall functionality of the NVU. This includes studying complex regulatory modes within the NVU during hypoxia sensing, oxygen supply maintenance, energy metabolism, and substance transportation, with the goal of providing a deeper understanding to inform research on the pathogenesis, intervention, and protection against hypoxic brain injury diseases.

QS and ZZ designed the study. XM collected and sorted references. QS designed and drew the figures. XM and QS wrote the initial draft. QS, XM and ZZ participated in preparing the final draft. ZZ provided supervision and advice. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by the Military Logistics Planning Project, grant number CLJ20J031.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.