1 Department of Biology, College of Science, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, 11671 Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Al-Azhar University-Assiut Branch, 71524 Assiut, Egypt

3 Physiology Department, College of Medicine, King Saud University, 11461 Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Nahda University, 62764 Beni-Suef, Egypt

5 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Badr University in Assiut, 71523 Assiut, Egypt

6 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, College of Pharmacy, Qassim University, 51452 Qassim, Saudi Arabia

7 Department of Life Sciences, Faculty of Science and Engineering, Manchester Metropolitan University, M1 5GD Manchester, UK

8 Molecular Physiology Division, Zoology Department, Faculty of Science, Beni-Suef University, 62514 Beni-Suef, Egypt

Abstract

Heavy metals can cause serious health problems that affect different organs. Cadmium (Cd) is an environmental contaminant known for its toxicological consequences on different organs. Hepatotoxicity is a serious effect of exposure to Cd with oxidative stress (OS) and inflammation playing a central role. Diallyl disulfide (DADS), an organo-sulfur compound found in garlic, is known for its cytoprotective and antioxidant effects. In this study, the effect of DADS on Cd-induced inflammation, oxidative stress and liver injury was investigated.

DADS was supplemented for 14 days via oral gavage, and a single intraperitoneal dose of Cd (1.2 mg/kg body weight) was administered to rats on day 7. Blood and liver samples were collected at the end of the experiment for analyses.

Cd administration resulted in remarkable hepatic dysfunction, degenerative changes, necrosis, infiltration of inflammatory cells, collagen deposition and other histopathological alterations. Cd increased liver malondialdehyde (MDA) and nitric oxide (NO) (p < 0.001), upregulated toll-like receptor (TLR)-4, nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB), pro-inflammatory mediators, and caspase-3 (p < 0.001) whereas decreased glutathione (GSH) and antioxidant enzymes (p < 0.001). Cd downregulated peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), a transcription factor involved in inflammation and OS suppression (p < 0.001). DADS ameliorated liver injury and tissue alterations, attenuated OS and apoptosis, suppressed TLR-4/NF-κB signaling, and enhanced antioxidants. In addition, DADS upregulated PPARγ in the liver of Cd-administered rats.

DADS is effective against Cd-induced hepatotoxicity and its beneficial effects are linked to suppression of inflammation, OS and apoptosis and upregulation of PPARγ. DADS could be valuable to protect the liver in individuals at risk of Cd exposure, pending further studies to elucidate other underlying mechanism(s).

Keywords

- heavy metals

- garlic

- diallyl disulfide

- hepatotoxicity

- oxidative stress

- inflammation

Exposure of humans to heavy metals (HMs) can cause serious health problems that affect the liver, kidney, nervous system, heart, and other main organs. Given the non-biodegradable nature of HMs, they accumulate within the body and disrupt normal function of the cells, leading to serious disorders that deteriorate over time [1, 2]. Cadmium (Cd) is one of the HMs that can pose serious health issues if reached the body in levels exceeding the permissible limits. It is a non-essential element known as an environmental pollutant that can reach the human body via multiple sources. Food, water, cigarette smoke and industrial activities such as mining, plastics, petroleum, stone quarrying, and batteries are sources of Cd [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. Exposure to Cd is on increasing trajectory in developing countries and this is associated with adverse effects on animals and human health [8]. It has been estimated that 60% of the absorbed Cd deposited in the liver and kidney and approximately 0.007–0.009% is excreted in feces and urine [9]. Cd has no specific channels and enters the cells via calcium (Ca) and zinc (Zn) channels where it accumulates and binds to proteins including metallothionein (MT), ultimately leading to cell death [10, 11]. Exposure to Cd for either short or long periods of time results in its accumulation in the liver which acts as the main site of HMs deposition. Studies on humans and animals revealed Cd accumulation in the liver, kidney, and many other organs [12, 13, 14], demonstrating its serious health consequences.

Hepatotoxicity represents one of the hazardous consequences of exposure to Cd

with oxidative stress (OS) playing a central role in the mechanism of toxicity

[1]. In humans exposed to Cd, a strong positive correlation between soil Cd

concentrations and fatty liver disease [15] and other metabolic alterations such

as type 2 diabetes [16] has been reported. High blood Cd levels were associated

with liver steatosis and fibrogenesis in both male and female human subjects

[17], and liver cirrhotic/cancer patients exhibited increased levels of serum Cd

[18]. Excess levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and consequently

OS provoked by Cd disrupt the cellular redox balance and activate inflammatory

responses and cell death [19]. ROS can activate many signaling molecules such as

toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 and subsequently nuclear factor-kappaB

(NF-

Plants are valuable sources of numerous components with beneficial

pharmacological properties. Garlic is a functional food that has beneficial

effects in preventing several disorders and toxicities [23]. The organic sulfur

compounds are believed to mediate the beneficial biological and health-promoting

activities of garlic [24]. Diallyl disulfide (DADS) is a major bioactive

organosulfur compound of garlic. DADS showed promising pharmacological

activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and protective efficacy

against infections, cancer and other disorders affecting different organs

[25]. The effect of DADS on inflammatory response in different disorders has been

well-acknowledged. In murine pancreatitis and lung injury, DADS was effective in

attenuating inflammation via suppressing NF-

Twenty-four male Wistar rats (180–200 g) were kept on a 12 h dark light cycle

under standard temperature (22

Serum transaminases (aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine

aminotransferase (ALT)), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH),

and albumin were measured using Bio-diagnostic (Giza, Egypt) kits. To determine

the content of liver malondialdehyde (MDA), reduced glutathione (GSH), and nitric

oxide (NO), and activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT),

specific kits from Bio-diagnostic (Giza, Egypt) were used. Tumor necrosis factor

(TNF)-

Liver samples were fixed in a 10% NBF for 24 h and then dehydrated in ethanol

and cleared in xylene. The samples were infiltrated in pure soft paraffin

followed by embedding in paraffin and 5-µm sections were cut. The

sections were stained with hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) [35], periodic acid-Schiff

(PAS) [35], and Sirius red [36]. Another set of sections were dewaxed,

rehydrated, and immersed in 0.05 M citrate buffer (pH 6.8) and then 0.3%

hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and protein block. The sections were probed

with anti-inducible NO synthase (iNOS), anti-cleaved caspase-3, and

anti-PPAR

The effect of Cd and/or DADS on TLR-4 and NF-

The findings are shown as mean

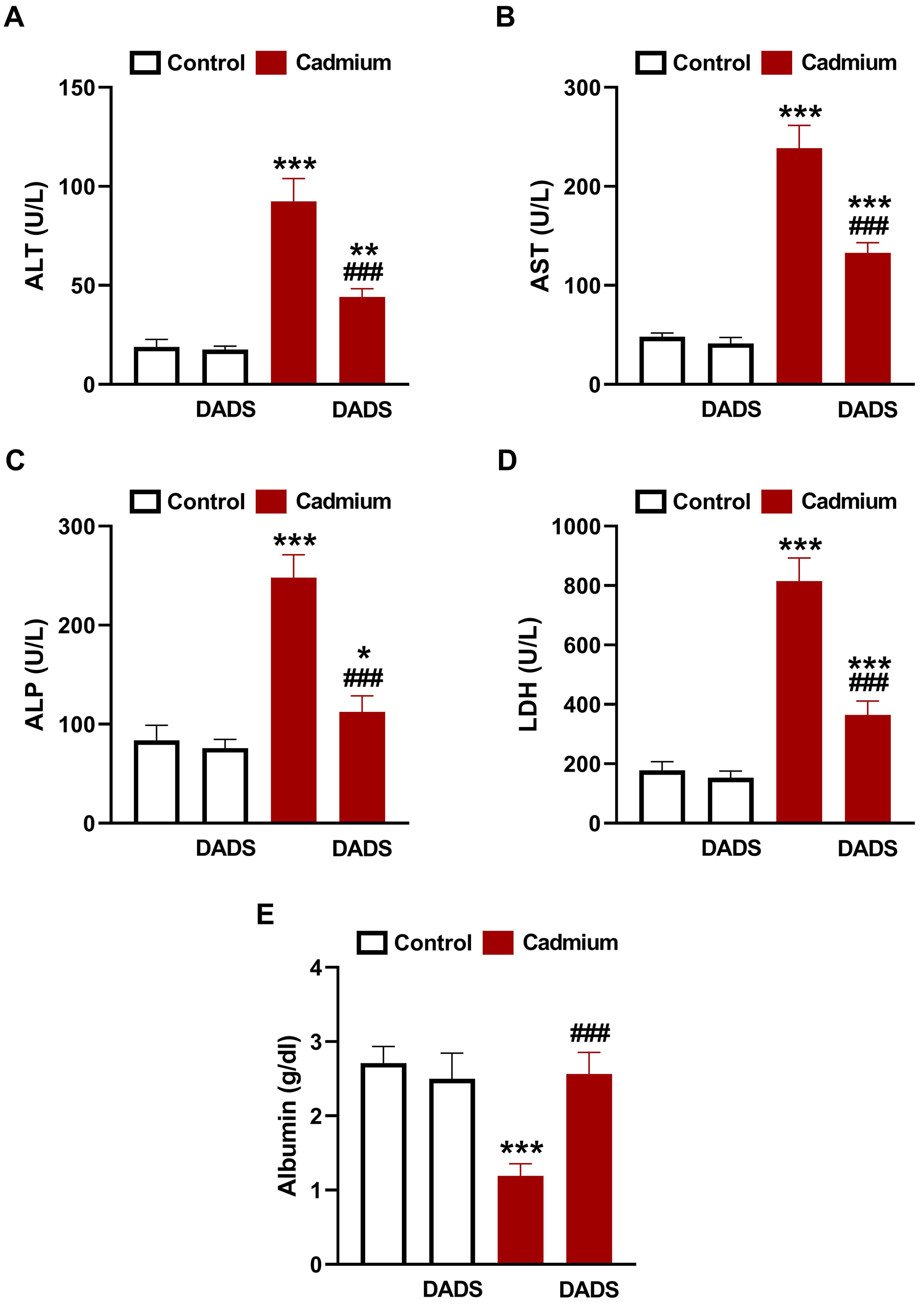

The biochemical findings revealed significant elevation in circulating ALT, AST,

ALP, and LDH (Fig. 1A–D) and declined albumin (Fig. 1E) in Cd-treated rats

(p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Diallyl disulfide (DADS) prevented Cd-induced liver injury.

DADS ameliorated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (A), aspartate

aminotransferase (AST) (B), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (C), lactate dehydrogenase

(LDH) (D), and albumin (E) in Cadmium (Cd)-administered rats. Data are mean

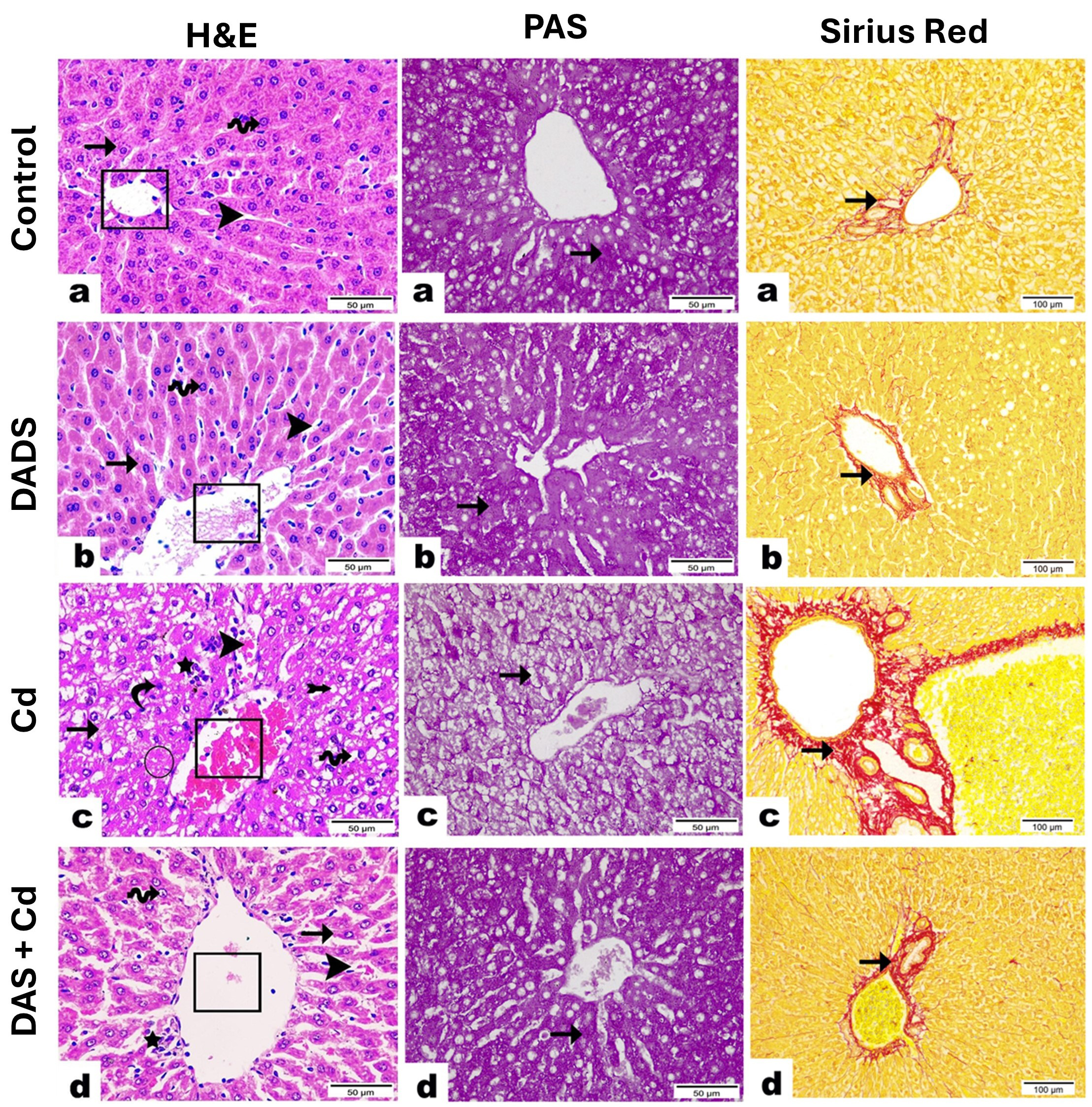

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Photomicrographs demonstrated the protective effect of Diallyl

disulfide (DADS) on histopathological alterations induced by Cadmium (Cd) in rat

liver. Hematoxylin & eosin (H&E): (a,b) Liver section from control (a) and

DADS-treated (b) groups exhibiting the normal central vein (cube) and hepatocytes

with central vesicular nucleus (wave arrow) arranged in regular cords (arrow) and

separated by blood sinusoids (arrowhead). (c) Liver section from Cd-administered

group revealing necrotic area (circle), loss of hepatic cord regularity (arrow),

congestion of the central vein (cube) and blood sinusoids (arrowhead), severe

hydropic degeneration with cytoplasmic vacuolation (wave arrow), deep basophilic

pyknotic nuclei of hepatocytes (curvy arrow), inflammatory cell infiltration

encircling central vein (star), and obvious appearance of fat cells in between

hepatocytes (arrow with tail). (d) Liver section from Cd-administered rats

treated with DADS showing a marked recovery represented by intact central vein

(cube), less congested blood sinusoids (arrowhead), and regular hepatic cords

(arrow). Most hepatocytes appear nearly normal with acidophilic cytoplasm and

central vesicular nuclei (wave arrow). However, few inflammatory cells observed

surrounding central vein (star). (

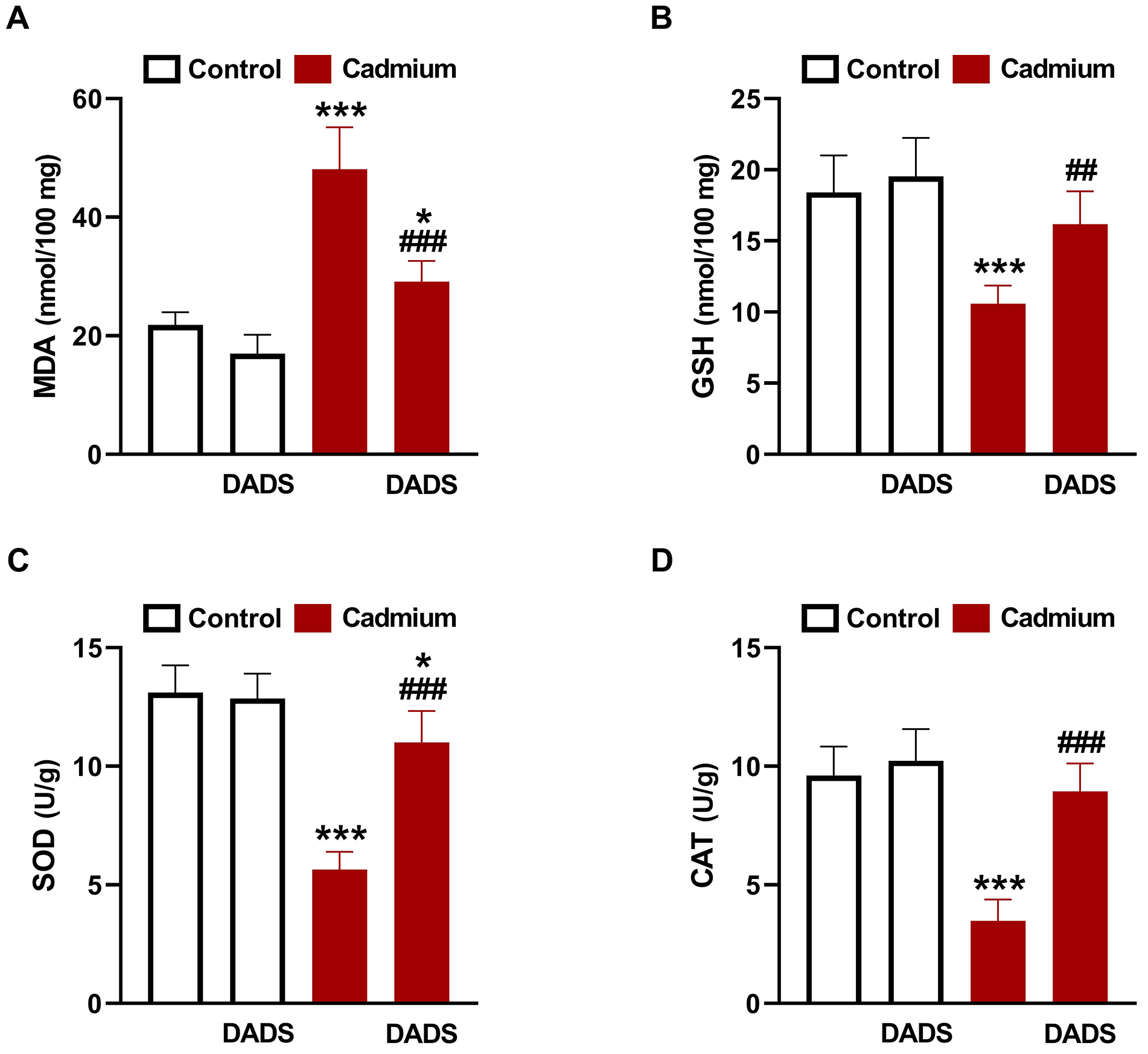

Administration of Cd increased liver levels of MDA (Fig. 3A), and decreased GSH

(Fig. 3B), SOD (Fig. 3C), and CAT (Fig. 3D) significantly (p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Diallyl disulfide (DADS) suppressed Cadmium (Cd)-induced liver

oxidative stress. DADS ameliorated liver malondialdehyde (MDA) (A), and increased

glutathione (GSH) (B), superoxide dismutase (SOD) (C), and catalase (CAT) (D) in

Cd-administered rats. Data are mean

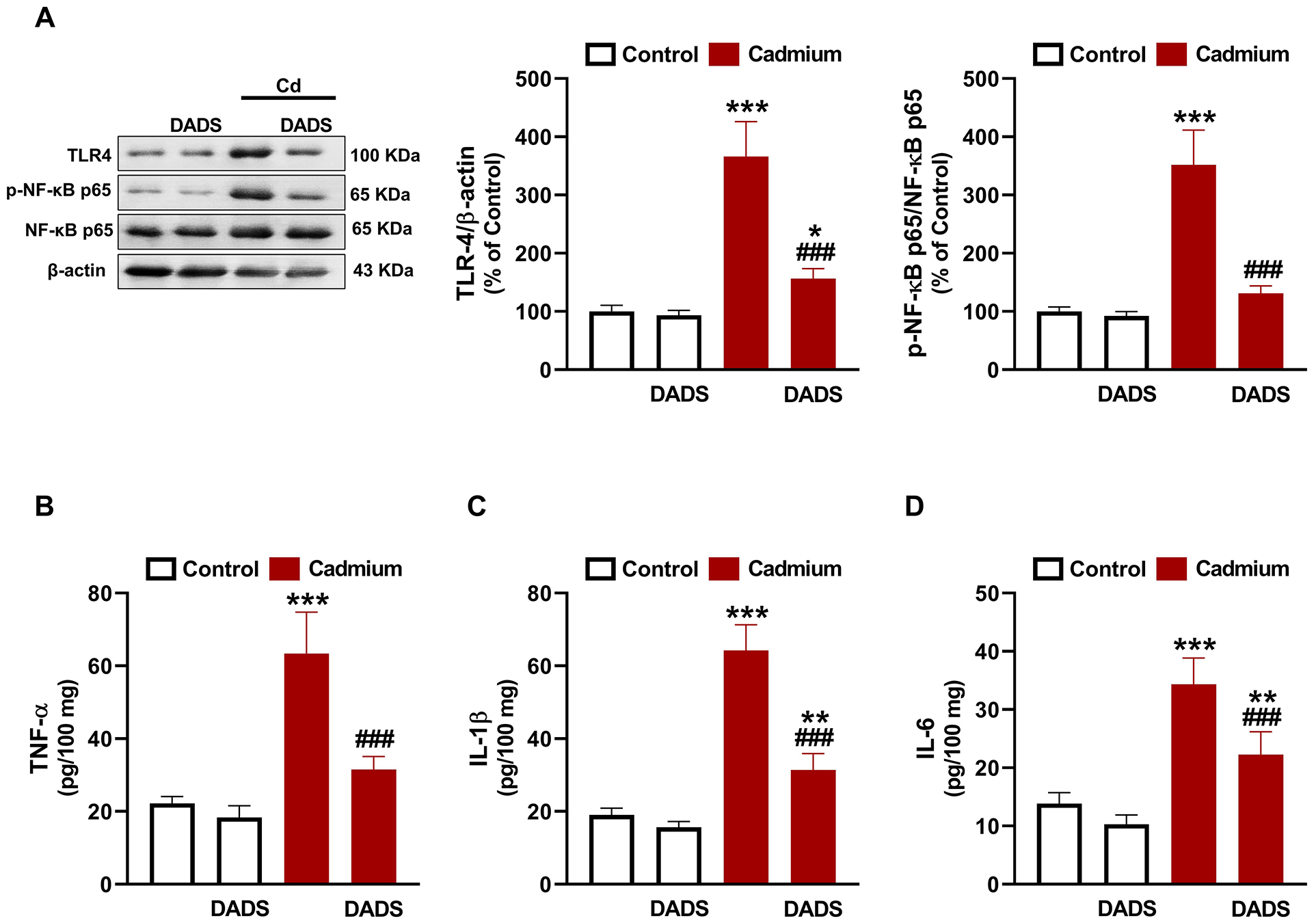

The effect of DADS on Cd-induced inflammation was evaluated by assessing

TLR-4/NF-

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Diallyl disulfide (DADS) attenuated Cadmium (Cd)-induced liver

inflammation. DADS downregulated toll-like recptor (TLR)-4 and nuclear

factor-kappaB (NF-

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Diallyl disulfide (DADS) downregulated inducible NO synthase

(iNOS) in liver of Cadmium (Cd)-administered rats. (A) Photomicrographs showing

upregulated iNOS in the liver of Cd-administered rats and the ameliorative effect

of DADS. (

Changes in cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 6) and PPAR

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

DADS downregulated cleaved caspase-3 in liver of Cadmium

(Cd)-administered rats. (A) Photomicrographs showing upregulated caspase-3 in

the liver of Cd-administered rats and the ameliorative effect of DADS.

(

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Diallyl disulfide (DADS) upregulated peroxisome proliferator

activated receptor gamma (PPAR

Hepatotoxicity and other liver disorders been reported as hazardous effects of exposure to Cd, particularly in developing and industrial countries [1, 8]. Inflammation and OS are key elements in Cd hepatotoxicity and the development of strategies to mitigate or prevent these processes can protect against liver injury in vulnerable individuals. This study demonstrated the protective role of DADS against Cd-induced OS, inflammation, and liver injury in rats.

Liver injury following Cd administration was evidenced by altered biochemical parameters (ALT, AST, ALP, LDH and albumin) of hepatocyte injury and histopathological alterations. Elevation of circulating ALT, AST, LDH, and ALP has been acknowledged in animals exposed to Cd [39, 40]. In adult humans, exposure to Cd resulted in elevated blood transaminases as reported by Kang et al. [41]. Exposure to Cd is associated with liver disorders, including steatohepatitis [15], and increased serum transaminases was closely associated with Cd levels [42]. Rats that received Cd showed declined serum albumin which along with the elevated transaminases denoted hepatocyte injury. The decrease in albumin was linked to decreased hepatic and renal Klotho-methylation as a result of Cd exposure [43]. Examination of tissue sections from Cd-exposed rats revealed severe alterations, including necrosis, loss of hepatic cord regularity, congested central vein and sinusoids, severe hydropic degeneration, pyknosis, inflammatory and fat cells infiltration, and increased collagen deposition. Previous studies have shown hyperplasia, necrosis, inflammatory cells infiltration, and apoptosis associated with Cd hepatotoxicity [44, 45]. A relationship between circulating Cd and liver steatosis and fibrogenesis in both male and female human subjects [17], and liver cirrhotic/cancer patients [18] was reported. This explained the increase in collagen deposition and fat cells in the liver of Cd-administered rats. In support of our findings, Li et al. [45] demonstrated a higher collagen peak in liver samples exposed to Cd by using Raman confocal imaging. DADS effectively mitigated liver injury in Cd-administered rats, supporting its previously reported hepatoprotective activity [31]. Treatment of ethanol-administered mice with DADS ameliorated circulating transaminases and prevented hepatic lipid deposition and tissue injury [31]. This protective efficacy of DADS was also established in rats challenged with carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) [46] where it effectively prevented tissue injury and ameliorated transaminases. These studies along with our findings demonstrated the efficacy of DADS to confer protection against different hepatotoxic chemicals.

The mechanism of Cd hepatotoxicity involves significant contribution of OS and

inflammation [1]. Given the reported antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties

of DADS [25, 28, 29], it is noteworthy assuming that these efficacies contributed

to its protection against Cd hepatotoxicity. Here, rats exposed to Cd showed

increased hepatic MDA, NO, NF-

DADS effectively mitigated OS and prevented inflammation and cell death in the

liver of Cd-administered rats. DADS attenuated lipid peroxidation (LPO),

suppressed TLR-4 and NF-

The beneficial role of DADS on Cd-induced OS and inflammation could be

associated with PPAR

This study shows new information on the protective role of DADS against

Cd-induced liver injury and the involvement of PPAR

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conceptualization, EHMH, and AMM; methodology, RSA, SMA, MAA, OAMA, MKM, EHMH, MFA, and AMM; formal analysis, RSA, EHMH, and AMM; investigation, RSA, OAMA, MKM, EHMH, and AMM; resources, SMA, MAA, and MFA; data curation, RSA, EHMH, and AMM; writing—original draft preparation, AMM; writing—review and editing, MFA and AMM; supervision, EHMH, and AMM; project administration, RSA, and AMM; funding acquisition, RSA. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The experimental protocol was approved by the ethics committee at Al Azhar University (Assiut - Egypt) (AZ-AS/PH-REC/28/24).

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project Number (PNURSP2024R381), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Researchers Supporting Project Number (PNURSP2024R381).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.