Contributed equally.

Background: Previous studies in the Western world and some Arab countries have shown that women seeking healthcare consider a variety of factors such as physician bedside manner, hospital affiliation, experience, competency, gender, and recommendations from friends among others. The objective of this study is to evaluate factors that affect Lebanese women’s choice of their obstetrician and gynecologist (ob-gyn). Materials and Methods: Quantitative data were collected from 199 respondents after administering a self-completion questionnaire created on “LimeSurvey” and sent via email to a random sample (n=848) of female employees at the American University of Beirut (AUB). SPSS was used to code and analyze the data. Results: Lebanese women value consultation quality (median score (MS) = 92%), convenience (MS = 80%), physician’s educational background (MS = 73.34%) and reputation (MS = 52%), more than physical qualities (MS = 40%), and physician’s gender (MS = 20%). Multivariate analysis showed that younger females care more about consultation quality (p = 0.01), Muslim women and village residents prefer a female physician (p = 0.02 and p = 0.01, respectively), and the woman’s level of education directly relates to the physician’s educational background (p = 0.01). Conclusion: These findings will help medical graduates, program directors, current practitioners, and hospital human resources managers to better understand and cater to the needs of the population they are serving.

Several studies in the Western world and in Arab countries have looked at factors that might affect a women’s choice of obstetrician and gynecologist (ob-gyn). Studies have emphasized on this issue, for two main reasons. First, the choice of an ob-gyn is one of the key decisions a woman needs to make in her life [1]. Second, studies have linked patient’s satisfaction with better adherence to treatment [2] and have thus aimed at clarifying the physicians’ characteristics that would amplify a patient’s overall contentment and would thus accentuate compliance and lead to better outcomes.

Initially, the literature has focused on the effect of gender on a woman’s choice of ob-gyn [3-5] However, when some published studies failed to consistently correlate gender preference and the actual gender of the chosen ob-gyn [6, 7], other factors and characteristics began to be studied such as bedside manners, hospital affiliations, experience, and professionalism among others [8, 9].

In the Arab world, studies have mostly focused on factors affecting a women’s choice of ob-gyn in specific religious groups [3, 10] without looking at a more global view of the matter. Lebanon, being an integral part of the Arab world with various religious groupings, constitutes an adequate setting to study and compare the importance of certain factors across religions.

The objective of this study was to evaluate factors that affect Lebanese women’s choice of their ob-gyn. The results of this study could be used to modify the local health system and to tailor physicians’ characteristics in a specific specialty to better satisfy patients’ needs.

This cross sectional study was performed at the American University of Beirut (AUB) between September and December 2015. The institutional review board at AUB, Lebanon approved all aspects of the study. A self-accomplished anonymous questionnaire was used to assess the factors that would affect a woman’s choice of her ob-gyn.

Invitation for participation was sent via email to a computer-generated list of 848 random female members at AUB. The participants could be part of the student body, faculty, administrative corps, or employees at the university and its medical center. The process of recruitment was halted after three reminders that were sent over a three-month period.

The questionnaire was developed in English on “LimeSurvey” and it included the factors previously studied in published literature in addition to few new characteristics. The first part of the questionnaire consisted of basic demographic information including age, marital status, level of education, religion, personal monthly income, place of residence, and frequency of ob-gyn visits. The items in the first part were answered by choosing the single most appropriate option. The second part included 23 characteristics subsequently regrouped into six categories each representing a specific factor: consultation quality, reputation, convenience, educational background, physical qualities, and gender (Table 1). The participants rated each of the characteristics within each factor using a Likert scale from 1 (not important) to 5 (extremely important). A score per participant was created for every factor and translated into a percentage, with 0% if all characteristics of a given factor rated as “not important” and 100% if all characteristics deemed “extremely important.”

| Factors | Statements |

|---|---|

| Consultation quality | -Known for professionalism (courtesy, empathy, good bedside manner) |

| Reputation | -Is recommended by my relatives and peers |

| Convenience | -Is simple to get appointment with |

| Educational background | -Has a degree from a prestigious university |

| Physical Qualities | -Is a male |

| Female Gender | -Is a female |

The final study outcomes were the factors considered important by women when choosing their ob-gyn, as well as the effect of the patient’s demographic features on the importance given to each of the six factors.

SPSS was used to code and analyze the data. A score of 50% was set as the cutoff to which the median score (MS) of every factor was compared. If the MS of a certain factor falls below 50%, that indicates the effect of this factor is not significant on the choice of ob-gyn. In order to determine the effect of socio-demographic features on every factor, both univariate and multivariate analyses were done with significance set at a confidence level of 95%.

A total of 199 full responses were collected; a response rate of 23.5%. Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants who completed the survey. The majority of women were < 36-years-old (64.8%), were married (57.8%), and had a postgraduate degree (57.3%). In addition, only 44.2% have regular yearly gynecological checkup with 15.6% reporting that they have never visited a gynecologist.

| Variables | Sample Distribution | |

|---|---|---|

| Age(year) | 18>35 | 64.8% |

| 36>51 | 26.1% | |

| ≥52 | 9% | |

| Marital Status | Single | 38.7% |

| Married | 57.8% | |

| Divorced/widowed | 3.5% | |

| Level of education | High school degree or less | 7.5% |

| Undergraduate degree | 35.2% | |

| Postgraduate degree | 57.3% | |

| Religion | Christian | 35.7% |

| Muslim | 50.3% | |

| Druze | 12.1% | |

| Others | 2% | |

| Personal monthly income(USD) | <1500 | 50.2% |

| >1500 | 49.7% | |

| Place of residence | City | 89.9% |

| Village | 10.1% | |

| Frequency of | When a need arises (pregnancy or others) | 30.2% |

| Gynecologist visits | Regular yearly checkup | 44.2% |

| Irregular check-ups | 10.1% | |

| None so far | 15.6% |

The six categories of factors that women rated to determine their relevance when choosing an ob-gyn will be analyzed separately.

With an MS of 92%, the consultation quality determined by a constellation of professionalism, communication skills, involvement in the decision-making, a lengthy consultation, and a clear explication of the interventions to be performed seem to strongly impact the woman’s choice of an ob-gyn. Using multivariate analysis, the woman’s age seems to have a significant effect on the weight given by the woman to consultation quality (p = 0.01): the younger the woman is, the higher the score attributed to consultation quality. In fact, 74.7% of women significantly affected by consultation quality were ≤ 35-years-old compared with 57.1 % of those not affected by this factor being in the same age group.

The MS of this factor was 52%, implying that a physician’s reputation, in terms of recommendation by others or personal knowledge, media appearances, being a prominent figure in the profession, and having a busy practice, significantly affects the women’s choice of ob-gyn. However, no particular socio-demographic variables act in favor of this choice.

Convenience, defined by the ease of taking an appointment or reaching the doctor, geographical closeness, and a reasonable consultation fee, had a MS of 80% and thus positively affected the woman’s choice of ob-gyn. Using univariate analysis, the woman’s age significantly correlated with the importance given to convenience (p = 0.002); the older the respondent, the less she cared about convenience. For example, only 2.8% of women significantly affected by this factor being older than 52 years of age compared with 16.7% of those not affected by convenience, being in the same age group. However, after controlling for other confounding variables through a multivariate analysis, the correlation between age and convenience lost its significance (p = 0.08).

Six different characteristics were grouped together to assess for the physician’s educational background and these were: being a graduate of a prestigious university, being a sub-specialist, had long years of experience, was always up-to-date, completed some training overseas, and was American board certified. The corresponding MS of 73% established educational background as an important factor affecting the women’s choice of ob-gyn.

Using univariate analysis, two socio-demographic features were shown to correlate with the importance given to the physician’s educational background: marital status (p = 0.01) and participant’s level of education (p = 0.01). Women who are not currently or previously married care more about the physician’s educational background. In fact, 44.3% of respondents significantly affected by the physician’s background are single compared with 33.3% of those not affected by this factor (p = 0.01). However, after the multivariate analysis, the correlation between woman’s marital status and importance of physician’s educational level became insignificant (p = 0.07). In addition, the participant’s own educational level was directly related to the significance given to the physician’s educational background, where 64.9% of respondents significantly affected by the physician’s education were themselves postgraduates compared with 50.0% of those not affected by this factor (p = 0.01.). Furthermore, 2.1% of respondents affected by this factor had a high school degree or less compared with 12.7% of those who are not. Importantly, this correlation between the woman’s personal educational level and the importance given to the physician’s educational level was maintained even after controlling for possible confounders (p = 0.01).

A young, elegant, good-looking male physician, with a nice clinic, who shared the woman’s religious beliefs, was evaluated to see the importance a woman attributes to her ob-gyn physical qualities. With a MS of 42%, it appears that physical qualities are not significantly taken into consideration by women when choosing their ob-gyn. Different socio-demographic variables do not alter this conclusion.

The MS was 20%, implying that the female gender of the physician is not a significant player in the process of decision-making in the selection of ob-gyn. Using univariate analysis, the following socio-demographic factors were shown to correlate with the importance given to an obgyn’s gender: age of the respondent (p = 0.03), her religion (p = 0.002), her monthly income (p = 0.01), and her place of residence (p = 0.01).

The younger she is, the higher the preference for a female care provider with 75.7% of respondents who scored higher than the median for this category being ≤ 35-years-old compared with 58.4% of the respondents who scored lower. However, using multivariate analysis, the relationship between age of the participant and importance given to physician’s gender lost significance (p = 0.07).

Religion was also seen to affect the importance given to the ob-gyn’s gender. Christians constituted only 20.3% of the population that scored higher than the median while they constituted a major portion of the respondents who scored below the median (44.8%). Muslims on another hand constituted 64.1% of respondents who gave great importance to female gender compared to 41.6% of respondents who did not care. Druze woman constituted an equal portion in both groups. A multivariate analysis showed that a statistically significant relationship (p = 0.02) still existed between participant’s religion and ob-gyn’s gender even after controlling for confounders.

Participant’s personal monthly income initially correlated with the importance given to ob-gyn’s gender. In fact, 56.8% of respondents who did not insist on female gender for their physician gained more than 1,500 USD per month compared with 37.8% of those who cared about female gender. This correlation was lost in the multivariate analysis (p = 0.22).

Lastly, village residents had a preference to a female physician, with 17.6% of those scoring higher than the median being village residents as opposed to only 5.6% of those scoring below the median (p = 0.01).

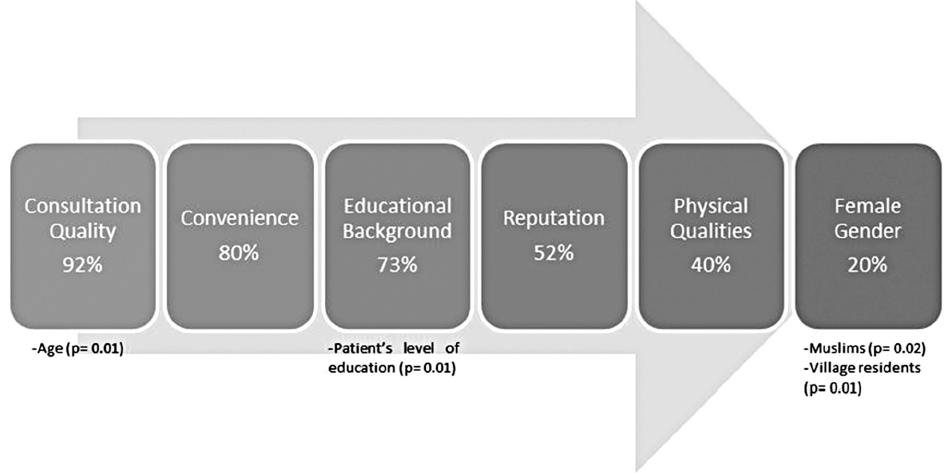

The present study showed that when choosing their obgyn, Lebanese women value most the consultation quality which comes ahead of convenience, the physician’s educational background, and his/her reputation. On the other hand, physical qualities and the gender do not seem to significantly affect the general population’s choice of their obgyn. These conclusions were altered when different sociodemographic variables were analyzed, highlighting the different individualities of each subpopulation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.— Factor’s order of importance by decreasing median score (in percentage).

The fact that younger patients care more about consultation quality can be attributed to several features of the personality and psychology of this age group. This is a delicate subpopulation that might be more fragile due to young age and fewer experiences in life, explaining the high value attributed to the physician’s courtesy, empathy, bedside manners, communication skills, and readiness for a lengthy consultation. These factors contribute to the quality of the medical encounter [11]. On another hand, older women might have acquired some kind of immunity which renders them less focused on the physician’s manners. This finding is somehow different than the conclusion of previous studies that showed that patient’s characteristics were independent of the importance given to each factor when choosing one’s physician [8].

In addition, there’s a growing desire of the young generation to take control of all aspects of their own life, which makes them willing to know everything related to the physical exam, work-up, and potential diagnosis, so they can share in the decision-making and be part of the management plan.

It is not surprising that the woman’s level of education directly relates to the physician’s educational background, as highly educated women expect their ob-gyn to have graduated from a prestigious university, to have long years of experience, and to remain up to date by continuing medical education. These might be a simple projection of the woman’s own academic achievements. Besides board certification and sub-specialized training, even when not pertinent to the woman’s main complaint, provide reassurance to the clients who value education, and about the quality of care this particular ob-gyn is going to provide. This is in accordance with previous studies where board certification was rated by women as being a major determinant of their decision [7] and where it was shown that most women value a physician’s clinical and educational expertise and take it into significant consideration to make an informed decision [8]. Moreover, it was previously shown that when noticing that their doctor was more competent, patients were more likely to be compliant [12].

Conflicting literature exists regarding woman’s preference for a female ob-gyn. While some studies show a notably significant preference of female ob-gyn [3], others concluded that gender was not a major characteristic that affecteds this decision [8, 13]. The observed variations are due to the difference in cultural, social, ethnic, and religious backgrounds of the populations studied as was mentioned in previous studies [7]. In a population like the present, where women do not seem to have a preference to a female physician, it is still notable that this might not apply to a sub-population of Muslims and village residents who continue to prefer a female physician. This can be attributed to some traditions and religious beliefs that make them more conservative. This is in agreement with previous studies that have also noted the different significance attributed to this criterion across religious ethnicities, concluding that Muslims and Hindi prefer being seen by a female ob-gyn [14].

This study had a number of limitations. In addition to the small sample size resulting from a modest response rate, all the respondents belonged to the same community of AUB, questioning the diversity of the sample population. However, the study design which took into account several socio-demographic variables might assist in overcoming this constraint.

Regarding the very design of the study, grouping of different physician’s characteristics together to study a single factor, might underestimate the role of independent characteristics in the selection process of the ob-gyn by the patient.

Despite the abovementioned limitations, this study had a great value being the first to assess the preferences of Lebanese women for attributes of obstetric and gynecologic care providers based on a PubMed search of the English literature until August 2016 using the keywords “obstetrics”, “gynecology”, “gender”, “patient preference”, “communication”, and “professionalism”. As previously shown, this type of study is important in each population to establish new ways of providing better healthcare services [7].

This work may have an important impact on the future structure of the medical workforce, service delivery, and postgraduate training in obstetrics and gynecology in the present Lebanese community. Results will help potential medical students who are interested in obstetrics/gynecology understand the factors that drive the women choice for their physician, consequently discovering if they will fit for such a profession [1]. Data will be used by the program directors as well to select the suitable candidates for their residency program. Moreover, results might benefit current practitioners to alter some variables to better satisfy the Lebanese market needs.

Last but not least, results will be highlighted by the human resources managers at the Lebanese hospitals while recruiting gynecologists and/or obstetricians, taking into consideration the socio-demographic variables of the patients they are serving.