1 Department of Psychology, University of La Frontera, 4780000 Temuco, Chile

2 Doctoral Program in Psychology, University of La Frontera, 4780000 Temuco, Chile

3 Department of Diagnostic and Evaluation Processes, Faculty of Health Sciences, Catholic University of Temuco, 4813302 Temuco, Chile

Abstract

In Chile, obesity and weight stigma significantly affect the quality of life and psychological well-being. Coping responses to stigma have a considerable impact on well-being. However, research on coping with weight stigma is limited. This study determined the psychometric properties of the Weight Stigma Coping Scale (WSCS, EAEP for Its Acronym in Spanish), which was created by the research team.

Two samples with university students from La Araucanía, Chile (N = 373 and N = 392), were included using a cross-sectional quantitative design.

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were applied, identifying two factors: adaptive and maladaptive coping. The results showed high internal consistency (α = 0.824; ω = 0.831) and convergent construct validity with body dissatisfaction, self-compassion, and internalized weight stigma.

The WSCS proved to be a valid and reliable tool for measuring coping strategies for weight stigma, with implications for psychological interventions aimed at improving the well-being of those facing this stigma.

Keywords

- weight stigma coping

- weight stigma

- factor analysis

- validity

- reliability

Chile is one of the ten countries with the highest rates of overweight and obesity. In 2019, 74.2% of adults were classified as having overweight or obesity (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2019; Vio del Río, 2018). Furthermore, individuals with large body sized experience daily discrimination and weight stigma (Gómez-Pérez et al, 2023; Hayward et al, 2017; Hayward et al, 2018), making this a highly relevant phenomenon in the Chilean context (Gómez-Pérez et al, 2023).

Weight stigma occurs in multiple contexts and stems from diverse sources such as family, friends, strangers, and even in workplaces and healthcare environments, making it a nearly unavoidable daily experience (Gómez-Pérez et al, 2023; Hayward et al, 2017; Hayward et al, 2018; Pearl and Puhl, 2018; Puhl et al, 2020). Weight stigma involves the denigration and devaluation of individuals based on their weight, rooted in negative stereotypes that associate excess weight with a lack of discipline and personal responsibility. This perspective ignores the multifactorial nature of weight as a chronic, prevalent, complex, progressive, and recurrent condition, influenced by behavioral, environmental, genetic, and metabolic factors (Ortiz and Gómez-Pérez, 2019; Sánchez-Carracedo, 2022; Tomiyama, 2014). This stigma perpetuates negative attitudes, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination against people with high weight, significantly impacting their quality of life and leading to psychological discomfort (Myers and Rosen, 1999; Sánchez-Carracedo, 2022; Tomiyama, 2014). Evidence suggests that weight stigma negatively affects body image, and psychosocial well-being, and is associated with higher levels of emotional dysregulation and suicidal risk (Bautista-Díaz et al, 2019; Douglas et al, 2021; Ortiz and Gómez-Pérez, 2019; Puhl and Brownell, 2006; Sánchez-Carracedo, 2022).

A common consequence of stigma is its internalization (Forbes and Donovan, 2019; Pearl et al, 2018; Puhl et al, 2018). This occurs when individuals adopt negative beliefs and stereotypes about their own weight as truths, resulting in psychological distress symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem (Alvear-Fernández et al, 2021; Forbes and Donovan, 2019; Hayward et al, 2018).

Weight stigma, along with its degree of internalization, influences the development of various coping responses (Gómez-Pérez et al, 2023; Hayward et al, 2018). Coping refers to the cognitive and behavioral efforts made to manage external and/or internal demands perceived as stressful. These strategies aim to help individuals adapt to or reduce the distress caused by stigmatizing experiences (Gustems-Carnicer et al, 2019; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Lazarus and Folkman, 1986). Two types of strategies have been identified: adaptive strategies, which predict well-being and better mental health, such as positive internal thinking, self-esteem, and reappraisal (Emmer et al, 2020; Hayward et al, 2017; Hayward et al, 2018; Kargari Padar et al, 2022); and maladaptive strategies, which are associated with lower well-being and decreased mental health (e.g., negative internal dialogue, disconnection, crying, and insolation), resulting in greater body dissatisfaction, depression, anxiety, stress and low self-esteem (Emmer et al, 2020; Hayward et al, 2017; Hayward et al, 2018; Kargari Padar et al, 2022; Sánchez-Carracedo, 2022).

People with overweight or obesity, the more they experience and internalize weight stigma, the more they tend to rely on maladaptive coping strategies (Hayward et al, 2018). Thus, psychological well-being is more affected by an individual’s response to stigma than by the stigmatizing situation itself (Puhl and Brownell, 2006). Despite its impact, research on weight stigma and coping remains limited, highlighting the need to further investigate this relationship and its consequences for health (Hayward et al, 2017; Himmelstein et al, 2018).

One approach to understanding coping with weight stigma is through specific scales designed to measure it (Pérez Gil et al, 2000). Coping strategies have been studied extensively in mental health, focusing on stress, emotions, and conflict resolution (Londoño et al, 2006), as well as in physical health contexts, such as managing a chronic disease like cancer (Macía et al, 2021). Although general scales exist to assess coping strategies instruments specifically designed to measure coping with weight stigma are limited. (Carver et al, 1989; Folkman et al, 1986; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Tobin et al, 1989).

Myers and Rosen (1999) developed the Coping Response Inventory (CRI), as a complementary measure to their Stigmatizing Situations Inventory (SSI), to assess how individuals cope with weight stigma. The CRI includes 99 items and 21 subscales, addressing dimensions such as negative internal dialogue, self-love, self-acceptance, and social support from non-fat individuals, among others. However, its extensive length limits its feasibility for practical application (Kargari Padar et al, 2022).

Subsequently, Hayward et al (2017) developed and validated a shorter version of the CRI (Myers and Rosen, 1999), demonstrating good psychometric properties and enabling a quick and efficient assessment of basic coping responses. This version includes two subscales, each with five items: Reappraisal Coping, where an example item is “I try to think about the good things that have happened to me” and Disengagement Coping, where an example item is “I avoid looking at myself in the mirror so I don’t have to think about my weight”. The response format is a five-point frequency scale ranging from never to always.

There is no evidence of weight stigma coping scales adapted to Spanish. The instruments by Myers and Rosen (1999) and Hayward et al (2017) have been used in their original language, developed and adapted in a context different from that of Spanish-speaking countries (Kargari Padar et al, 2022). For this reason, it is relevant to determine the psychometric properties of a scale that measures coping strategies for weight stigma, developed in the national context, in Spanish, and culturally relevant. Such a scale facilitates understanding the strategies that people with high weight develop in response to stigmatizing situations and can be used by professionals from various health disciplines. Therefore, having a valid, reliable scale created in this context constitutes a milestone in diversifying the existing scales, which are currently being adapted from other countries, allowing other regions of Latin America to have it available for use and application.

Consequently, the general objective of this research was to determine the psychometric properties of the Coping with Weight Stigma Scale. The specific objectives were: (1) to determine the reliability evidence of the scale, (2) to identify the factorial validity evidence of the Coping with Weight Stigma Scale, and (3) to identify the convergent construct validity of the scale.

Participants were university students between 18 and 29 years old who resided in the Araucanía region, Chile. They were selected through two non-probabilistic convenience samples. The sample size was determined based on the characteristics of the FONDECYT Project (Initiation Grant No. 11190362), considering a statistical power of 0.8, a nominal alpha of 0.05, and the recommendations for exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis using robust estimates (Lloret-Segura et al, 2014).

The first sample included 373 participants with a mean age of 21 (SD = 2.278). Of these, 62% were female, 36% male, and 1.6% non-binary. Forty-six percent self-perceived identified as belonging to a medium socioeconomic level (SES), 77% were exclusively students, 85% lived in urban areas, and 14% lived in rural areas. Regarding the percentages in the different degrees, 41.01% corresponded to health careers (e.g., nutrition, occupational therapy, medical technology, medicine, nursing, kinesiology, dentistry, among others), 17.15% corresponded to careers related to engineering (e.g., civil engineering, commercial engineering, geomensura, computer science, administration, among others), 21.17% corresponded to careers in social sciences and humanities (e.g., pedagogy, baccalaureate, social work, law, among others), 13.13% were careers in agricultural sciences (e.g., veterinary medicine, agronomy, biotechnology) and 7.50% corresponded to technical careers.

The second sample consisted of 392 participants with a mean age of 22 years (SD = 2.169). Sixty-six percent of the sample were female, 33% male, and 0.7% non-binary. Forty-eight percent reported belonging to the middle SES, 81% exclusively students, 88% lived in the urban areas, and 12% lived in rural areas. Regarding the percentages in the different degrees, 48.97% corresponded to health careers, 21.93% corresponded to careers related to engineering, 20.91% corresponded to careers in social sciences and humanities, 5.61% were careers in agricultural sciences and 2.55% corresponded to technical careers.

The inclusion criteria were being a university student and residing in La Araucanía region, Chile. The exclusion criteria were being a psychology student or being pregnant. Additionally, individuals who participated in the stages of the FONDECYT initiation project 11190362, which had 3 stages, the first qualitative and the second and third quantitative, were excluded, so that participants could only enroll in one of the project stages.

This scale was developed by the research team of the Laboratory of Stigma, Discrimination, Health and Food (LEDSA for its acronym in Spanish) within the framework of the FONDECYT project. Initially, a qualitative study was conducted comprising 45 semi-structured interviews with a population with diverse socio-demographic characteristics, such as age and socioeconomic level, as well as with people with different body compositions according to body mass index (normal weight, overweight, and people with obesity were part of the sample). The interview guideline included general questions about beliefs associated with obesity, exposure to weight-related comments, experiences of weight stigma, sources of this stigma, and ways of responding to these situations. Subsequently, content analysis was performed, which was triangulated by the research team, identifying the most relevant categories. This process led to the creation of 18 items, which were then evaluated by expert judges using criteria of clarity, coherence, relevance, and sufficiency. As a result, two additional items were incorporated, bringing the total to 20 items. These were pilot-tested with a sample using cognitive interview techniques to assess item comprehension and identify potential errors, culminating in the application of the final scale. The instrument consists of 20 items that assess how people respond to stigmatizing situations, using a five-point Likert-type response format (never, rarely, occasionally, almost always, always), where an example of an item is “I wear oversized clothes to hide my body”. Detailed psychometric properties of the scale are provided in the results section, and the final solution comprises 16 total items.

The Neff SCS (2003) was adapted for Spanish-speaking populations in Mexico by López-Tello et al (2023). It evaluates how people treat themselves in adverse situations through 26 items across six factors: self-kindness, self-judgment, shared humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification. Example items include: “I try to be loving to myself when I feel emotional pain” and “When I feel discouraged and sad, I remind myself that there are many other people in the world who feel like me”. Responses are provided on a five-point frequency scale ranging from almost never to always. In this study, the scale demonstrated adequate (

The BSQ-14 developed by Dowson and Henderson (2001), was validated in Spanish by Franco-Paredes et al (2018) and later adapted for Peruvian university women by Izquierdo-Cardenas et al (2021). The questionnaire measures dissatisfaction with body image related to weight and body shape through 14 items. An example item is: “Seeing yourself in a mirror has made you feel bad about your figure?”. Responses are given on a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from never to always. In this study, the scale demonstrated excellent reliability (

This scale was developed by the LEDSA research team within the FONDECYT project. It contains 11 items, using a five-point Likert-type response format. An example item is: “All the time I am thinking that my weight is a problem”. All items are phrased in the same direction, where higher scores indicate greater internalized weight stigma. In this study, the scale demonstrated excellent reliability (

A sociodemographic questionnaire was designed to collect sample information, including variables such as age, residence, and socioeconomic level, among others.

To develop this scale, three studies were conducted within the FONDECYT initiation project 11190362, which provided the necessary data to achieve the research objectives. The project was approved by the Scientific Ethical Committee of the University of La Frontera (Protocol Number: 097-19). Informed consent forms were provided, explaining the study objectives, voluntariness of participation, confidentiality, procedures, and duration. Additionally, participants were informed they would receive monetary compensation of five thousand Chilean pesos (€4.75) for sample one via electronic transfer and ten thousand Chilean pesos (€9.50) in cash for sample two.

Data collection was conducted through advertisements on social and posters in universities in Temuco. Interested individuals were invited to participate and received a link via the QuestionPro platform that included the informed consent form. This document outlined the study’s objectives, voluntary participation, and confidentiality, along with detailed procedures. Participants were then asked to remotely complete a set of psychological instruments.

For sample one, the procedure took them approximately 20 minutes, after which participants received five thousand Chilean pesos (€4.75) via electronic transfer. For sample two, the procedure included a bioimpedance evaluation, requiring participants to visit the laboratory. This process took approximately 30 minutes, including 10 minutes for the bioimpedance assessment. Participants were compensated with ten thousand Chilean pesos (€9.50) in cash.

A preliminary analysis of the data was first conducted to identify the presence of missing data and to assess compliance with bivariate and multivariate normality, using the Shapiro-Wilk (W) and Mardia tests. For the Shapiro-Wilk tests, values between 0 and 1 were considered adequate, noting that smaller W values indicate rejection of normality, while a value of one suggests normality. A p-value

Subsequently, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted using the first sample (n = 373) to identify latent variables or common factors that explain responses to the scale items (Lloret-Segura et al, 2014). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) coefficient was calculated to determine the adequacy of the data for factor analysis, with values close to one indicating the presence of latent factors (Kaiser, 1974). Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was used to assess whether the correlations between items were significant.

To facilitate the interpretation of the factors, an Oblimin rotation was applied to the factor loadings matrix (Guzmán Alanya, 2021). Factor loadings (

To validate the identified structure, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted with the second sample (n = 392). This analysis also provided evidence for the validity of theoretical deductions derived from the structure (Pérez Gil et al, 2000). Construct validity evidence based on the internal structure was evaluated using the following goodness-of-fit indices: Chi-square (

To determine the evidence for convergent construct validity, scores for each factor of the Weight Stigma Coping Scale were examined with the Self-Compassion Scale, the Body Shape Questionnaire, and the Internalized Weight Stigma Scale, which was assessed by Spearman’s correlation (rho). Values of rho

Descriptive, bivariate, reliability, CFA, convergent construct validity, and structural equation modeling analyses were performed using JASP (Version 0.18.3, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and Stata/BE (Version 17.0; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). Structural equation modeling was carried out using the Lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) available for R Studio software (Version 2022.07.1; Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA, USA). The EFA was conducted using FACTOR (Version 12.04.01; Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, Spain).

The results of the descriptive statistics of the EAEP (for Its Acronym in Spanish) items in both samples, as well as the total scores of the self-compassion, body dissatisfaction, and internalized weight stigma scales in the second sample, are presented in Table 1.

| Scale | Sample 1 (n = 373) | Sample 2 (n = 392) | |||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Weight Stigma Coping Scale (EAEP for Its Acronym in Spanish) | |||||

| Item 1 | 2.109 | 1.172 | 1.908 | 0.990 | |

| Item 2 | 2.438 | 1.454 | 2.324 | 1.352 | |

| Item 3 | 3.107 | 1.416 | 2.888 | 1.369 | |

| Item 4 | 2.219 | 1.148 | 2.108 | 0.964 | |

| Item 5 | 2.086 | 1.175 | 1.868 | 0.962 | |

| Item 6 | 2.657 | 1.083 | 2.734 | 1.053 | |

| Item 7 | 2.498 | 1.250 | 2.346 | 1.096 | |

| Item 8 | 2.208 | 1.220 | 2.002 | 1.088 | |

| Item 9 | 2.321 | 1.157 | 2.179 | 1.032 | |

| Item 10 | 1.926 | 1.221 | 1.683 | 1.058 | |

| Item 11 | 2.851 | 1.354 | 2.635 | 1.231 | |

| Item 12 | 3.018 | 1.413 | 3.065 | 1.352 | |

| Item 13 | 3.117 | 1.374 | 3.245 | 1.358 | |

| Item 14 | 2.723 | 1.384 | 2.582 | 1.296 | |

| Item 15 | 2.934 | 1.496 | 2.746 | 1.376 | |

| Item 16 | 2.373 | 1.281 | 2.389 | 1.211 | |

| Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) | 2.982 | 0.462 | |||

| Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ-14) | 3.153 | 1.145 | |||

| Internalized Weight Stigma Scale (EEPI-11 for Its Acronym in Spanish) | 2.691 | 0.801 | |||

Note: M and SD represent the mean and standard deviation, respectively.

Regarding the initial treatment of the data, it was observed that the data did not meet bivariate or multivariate normality assumptions, as both the Shapiro-Wilk test and the skewness and kurtosis tests were statistically significant (p

A polychoric correlations matrix was generated to account for the ordinal nature of the variables (Lloret-Segura et al, 2014). Prior to the conducting EFA, sampling adequacy was evaluated. The KMO value was 0.88931, and Bartlett’s test indicated significant sphericity (

A parallel analysis identified a two-factor structure underlying the 20 items, with eigenvalues greater than one. The first factor explained 38.389% of the construct’s variance, while the second factor accounted for 51.504% (Timmerman and Lorenzo-Seva, 2011).

When interpreting the factors with an Oblimin rotation, items 9, 13, 14, and 15 were excluded due to factor loadings below 0.3 (Hair et al, 2010; Hulland, 1999; Nunnally, 1978). The remaining items were grouped into two factors: the first consisted of 4 items, and the second factor comprised 12 items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.525 to 0.850 (see Table 2).

| Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

| 1. Evito mirarme al espejo | 0.748 | |

| I avoid looking at myself in the mirror | ||

| 2. Evito pesarme | 0.783 | |

| I avoid weighing myself | ||

| 3. Pienso constantemente en cómo bajar de peso | 0.826 | |

| I constantly think about how to lose weight | ||

| 4. Evito comer | 0.811 | |

| I avoid eating | ||

| 5. Hago alguna dieta para perder peso | 0.603 | |

| I go on a diet to lose weight | ||

| 6. Como mucho más de lo habitual | 0.525 | |

| I eat much more than usual | ||

| 7. Evito pensar en mi cuerpo | 0.731 | |

| I avoid thinking about my body | ||

| 8. Me aíslo o trato de evitar situaciones sociales | 0.746 | |

| I isolate myself or try to avoid social situations | ||

| 9. Me pongo a la defensiva | 0.686 | |

| I become defensive | ||

| 10. Evito ir a controles médicos o hacerme exámenes | 0.598 | |

| I avoid going to medical check-ups or getting tests done | ||

| 11. Uso ropa ancha para ocultar mi cuerpo | 0.755 | |

| I wear loose clothing to hide my body | ||

| 12. Les explico a las personas sobre la importancia de no discriminar por el peso | 0.768 | |

| I explain to others the importance of not discriminating based on weight | ||

| 13. Trato de pensar que el problema lo tienen las personas que discriminan | 0.850 | |

| I try to think that the problem is with people who discriminate | ||

| 14. Busco apoyo de personas cercanas (pareja, amistades, etc.) | 0.547 | |

| I seek support from people close to me (partner, friends, etc.) | ||

| 15. Evito tomarme fotos de cuerpo completo | 0.751 | |

| I avoid taking full-body photos | ||

| 16. Veo contenido que promueve la aceptación corporal | 0.558 | |

| I watch content that promotes body acceptance |

Note: Own elaboration; the 4 items with loadings

The Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonald’s Omega coefficients to assess reliability in this first sample were

The two-factor structure identified in the EFA was tested using CFA. The analysis yielded the following goodness-of-fit indicators (

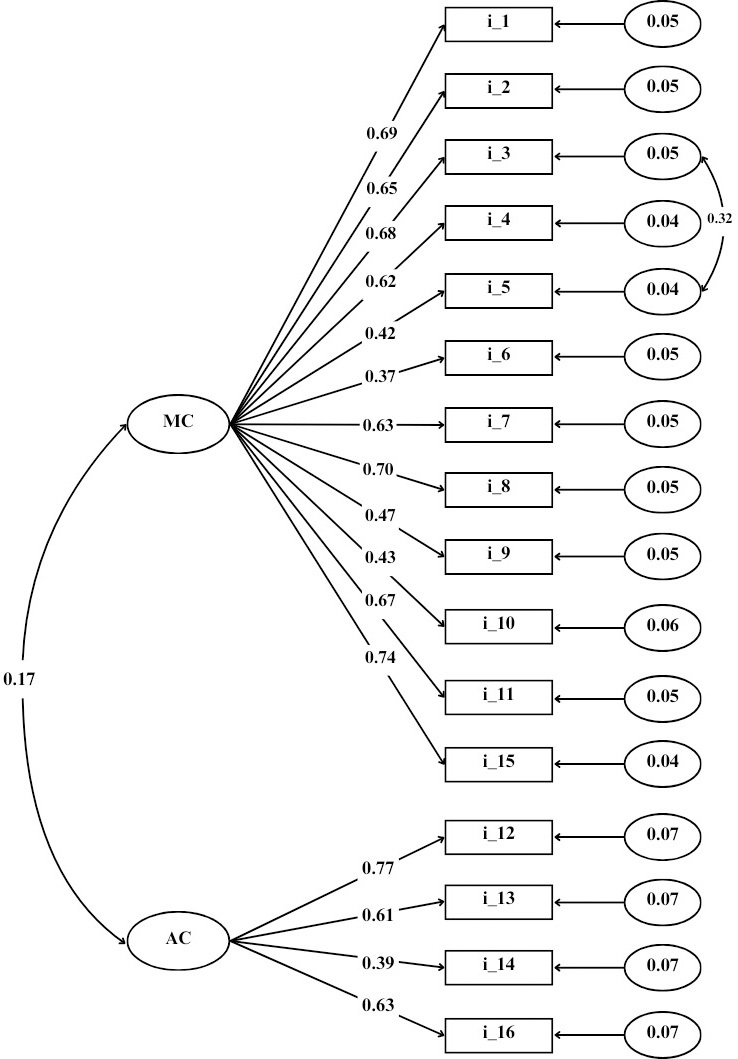

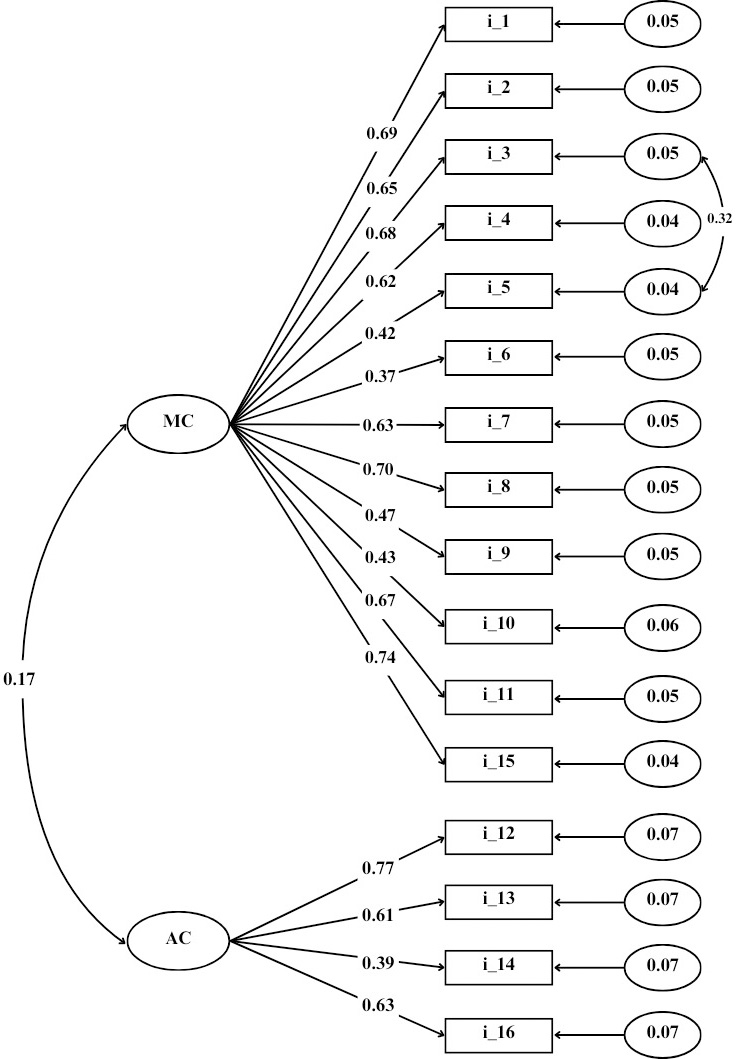

The first factor included 4 items reflecting adaptive coping with stigma, while the second factor consisted of 12 items representing maladaptive coping with stigma (see Fig. 1). Reliability in the second sample was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonald’s Omega coefficients, resulting in

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Two-factor structure of the EAEP (for Its Acronym in Spanish). Note: Own elaboration. MC, Maladaptive Coping; AC, Adapting Coping; i, Item.

Analysis of the EAEP (for Its Acronym in Spanish) factors (see Table 3) revealed that the adaptive coping factor showed a significant but weak correlation with SCS (rho = 0.282; p

| Weight Stigma Coping Scale (EAEP for Its Acronym in Spanish) | Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ-14) | Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) | Internalized Weight Stigma Scale (EEPI-11 for Its Acronym in Spanish) | |

| Adaptative coping | rho | 0.045 | 0.282 | –0.036 |

| p value | 0.376 | 0.481 | ||

| Maladaptive coping | rho | 0.805 | 0.322 | 0.754 |

| p value |

Note: Own elaboration.

This instrumental research aimed to determine the psychometric properties of the Weight Stigma Coping Scale (EAEP for Its Acronym in Spanish). First, the EFA revealed a two-factor structure, suggesting that weight stigma coping strategies can be categorized into two dimensions: adaptative coping and maladaptive coping. The CFA confirmed this structure, demonstrating good fit indices and factor loadings above the suggested cutoff point (Hair et al, 2010). These results validate the bifactorial structure of the EAEP, indicating it is an appropriate tool to measure weight stigma coping strategies in the Chilean adult population. The identification of two factors suggests that individuals may simultaneously employ both adaptive and maladaptive strategies to cope with weight stigma, consistent with previous research supporting the coexistence of multiple coping strategies in discriminatory and stressful situations (Emmer et al, 2020; Hayward et al, 2017; Hayward et al, 2018; Kargari Padar et al, 2022; Myers and Rosen, 1999; Sánchez-Carracedo, 2022). However, the low correlation between the factors suggests that while both strategies may coexist, one type may dominate in some individuals.

Regarding the EAEP, it is important to highlight that the scale was originally composed of 20 items, with eight representing adaptive coping and 12 corresponding to maladaptive coping. Removing items with low factor loadings ensures that these items do not weaken the latent construct and improves the scale’s validity and reliability (Kline, 2016). Consequently, removing four items from the adaptive coping factor enhances the model’s interpretability, even though this factor now has fewer items than the maladaptive coping factor, since overall, the global indicators of fit are adequate for the final solution of 16 items. The lower number of items to measure adaptive coping compared to maladaptive coping is a result similar to that reported in the literature (Puhl and Brownell, 2006), this may be because the adaptive coping responses of reappraisal and reevaluation (Himmelstein et al, 2018) require the use of social and psychological resources that contribute to greater compassion and body acceptance (Hayward et al, 2017), process involving increased literacy in seeking psychological help and making the problem of stigma more visible (Gerend et al, 2021), whereas maladaptive responses can be easily triggered by the negative experience of being discriminated against and stigmatized (Gómez-Pérez et al, 2021).

In terms of convergent construct validity, the observed correlation between adaptive coping and self-compassion aligns with findings in other studies, suggesting that self-compassion responses to discriminatory experiences promote healthier and more adaptive coping strategies (Hayward et al, 2017; Pullmer et al, 2021). Self-compassion serves as a personal resource and a protective factor, fostering effective coping with psychological distress by encouraging kindness over self-judgment (Athanasakou et al, 2020; Ewert et al, 2021; Fekete et al, 2021; Pullmer et al, 2021). Conversely, the significant positive correlation between maladaptive coping and both internalized weight stigma and body dissatisfaction is consistent with theoretical expectations. Previous research demonstrates that maladaptive coping strategies are strongly associated with increased internalization of weight stigma and body dissatisfaction (Hayward et al, 2018; Himmelstein et al, 2020; Kargari Padar et al, 2022). Evidence suggests that weight stigma predicts poorer psychological well-being through stigma internalization, which is linked to negative body image perceptions and heightened mental health symptoms (Hayward et al, 2018; Pearl and Puhl, 2018; Sánchez-Carracedo, 2022). This internalization often leads to a greater reliance on maladaptive coping responses, exacerbating psychological outcomes such as body dissatisfaction, depression, anxiety, stress, and lower self-esteem (Hayward et al, 2017; Hayward et al, 2018). A detrimental cycle is thus anticipated, wherein frequent exposure to weight stigma frequency, weight stigma internalization, and maladaptive coping, perpetuate poor psychological well-being (Hayward et al, 2018).

The EAEP demonstrates robust psychometric properties and provides a reliable, valid tool for assessing weight stigma coping strategies in the Chilean adult population. Furthermore, as a brief scale consisting of 16 items and easy to administer, it could enhance participation rates and lessen fatigue and other discomforts that might impact the quality of self-report measures (Kemper et al, 2019). Its brevity and simplicity enable its use across various disciplines, facilitating a broader understanding of the strategies that individuals with higher weight develop in response to stigmatizing situations, thereby contributing to a more comprehensive approach to obesity.

The EAEP could serve as a useful screening tool. International recommendations to weight stigma in healthcare settings emphasize the importance of identifying whether an individual has experienced stigma. Applying this scale and discussing its results with the user could initiate conversations about stigma and the strategies they employ to cope with it (Rubino et al, 2020). Moreover, by detecting individuals’ coping strategies, the scale could facilitate early and appropriate interventions, which are critical for effectively addressing stigma. The use of this scale in diverse settings could enable quick identification of individuals needing additional support, allowing health professionals to develop personalized and effective intervention plans (Benítez Brito et al, 2021; Sánchez-Carracedo, 2022).

This study is not without limitations. One limitation relates to the final structure of the scale, where maladaptive coping strategies were measured with 12 items, while adaptive coping strategies were measured with 4 items. This underrepresentation is consistent with findings by Hayward et al (2017), who encountered similar challenges with adaptive coping validating the short version of the CRI and presented complications in the validity evidence regarding the indexes of adaptive coping. This could be because maladaptive coping prevails over adaptive coping due to the high frequency of weight stigma experiences, which leads to poor psychological well-being, with greater stress and less cognitive control, which fosters the internalization of stigma and the use of maladaptive coping strategies (Hayward et al, 2018; Sutin et al, 2016). Another limitation of the study is that the psychometric properties were evaluated in an adult, but university population, which implies caution with the generalization of the results to the general adult population.

This is the only study that has evaluated evidence of validity and reliability of this scale, so it is necessary to continue investigating its psychometric properties in different populations. In this sense, it would be relevant to evaluate the metric invariance of the scale (Pedrero and Manzi, 2020), to determine whether it behaves consistently among different groups, such as men and women or people with different body composition. Also, it would be relevant to evaluate the psychometric properties of this scale in the adolescent population, to assess and know how they cope with weight stigma, given that in Chile between 2017 and 2020 an increase in the prevalence and hospitalizations of eating disorders was observed in this population, which is alarming since adolescence is a crucial stage for identity, self-esteem and self-concept, aspects that can be strongly affected by stigma and its coping (Adelardi, 2022; López-Gil et al, 2023).

Future research should investigate why maladaptive coping appears more common than adaptive coping, identifying possible factors that could be mediating this relationship. Finally, as family dynamics are linked to stress response styles, it would be important to explore how families, being one of the main sources of stigma, could influence the development of different coping strategies. Family dynamics could significantly shape devaluative beliefs that persist into adulthood, warranting further examination (Foster et al, 2024; Hayward et al, 2017).

The present study provides evidence supporting the reliability and validity of a scale designed to assess coping strategies in response to weight stigma, using a sample of 765 Chilean university students. The instrument comprises 16 items distributed across two dimensions: adaptive coping (4 items) and maladaptive coping (12 items). The adaptive coping dimension showed evidence of convergent criterion validity through a positive association with a self-compassion scale. In contrast, the maladaptive coping dimension was positively correlated with body dissatisfaction and internalized weight stigma. Internal consistency indices, assessed through Omega and Cronbach’s alpha, were satisfactory for both dimensions. These findings suggest that the scale may constitute a useful tool for healthcare professionals and researchers aiming to evaluate coping responses to weight-based stigmatization in university populations.

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to they are currently being processed, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conceptualization: DGP, TAA, PAS, JFD, PNN, CRE; Data curation and Formal analysis: FBG, TAA, PAS, JFD, PNN, CRE; Funding acquisition: DGP; Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation and Writing—review & editing: DGP, FBG; Resources: DGP; Visualization and Writing—original draft: TAA, PAS, JFD, PNN, CRE. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Scientific Ethical Committee of the University of La Frontera (Protocol Number 097-19). All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study.

We would like to express our gratitude to all the participants in the project and to the research laboratory team who supported the data collection, particularly Mr. Abner Silva, MSc, and Mr. Rodrigo Leviman, B.Sc.

This study was funded by ANID/CONICYT through the FONDECYT Initiation Project number 11190362, whose principal researcher is Dr. Daniela Gómez-Pérez, and by the Research Directorate, University of La Frontera, Support PP24-0029.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.